The weapons of an English medieval knight in combat included the long sword, wooden lance with an iron tip, metal-headed mace, battle-axe, and dagger. Trained since childhood and practised at tournaments, the skilled knight could inflict fatal injuries on even an armoured opponent. The sword, symbol of the chivalric code and his noble status, was above all the knight's most important weapon. With a heavy blade one metre in length, a 'great sword' had to be held with both hands and was remarkably stable in design from the 11th to 15th century CE. A mounted knight wielding a lance was a fearsome enough sight but a dismounted one swinging a sword that could sever limbs with one blow was an awesome psychological weapon in itself.

Training

There were several types of knights who fought in an army during wartime or performed guard duty in a castle. The largest group was composed of household knights, those who permanently served a specific lord and rode with him in war. Then there were those who were obliged to serve a lord as a knight as a form of feudal service. Another type was the mercenary knight who simply fought for whoever was willing to pay him. Finally, there were knights who belonged to a specific order such as the Templar Knights or Knight Hospitallers. Naturally, the quality and number of weapons a knight possessed depended on either the wealth of his lord or himself but this difference was largely manifested in decorative and material elements. Certain weapons were common to most knights on the medieval battlefield.

Proficiency in the use of weapons must have varied greatly between the professional knights and those performing a fixed-term of service. Young noble males would have been trained in weaponry from the age of around 10, and they would have become squires (trainee knights) from age 14. They practised with such devices as the quintain - a rotating arm with a shield at one end and a weight at the other. A knight had to hit the shield and keep riding on to avoid being hit in the back by the weight as it swung around. Another device was a suspended ring which the knight had to catch and remove with the tip of his lance. Riding a horse at full gallop and cutting at a pell or wooden post with one's sword was another training technique. A knight would have been practised at using the bow and perhaps even crossbow but, being deployed as part of a cavalry unit, did not usually use these weapons on the battlefield. When fully trained, a squire could be made a knight by their lord, usually when between the ages of 18 and 21. The martial training continued after that; after all, a fit and capable knight who could move in heavy armour, cope with the limited vision offered by his helmet, and effectively wield a sword or lance stood a much better chance of riding away from the carnage that was the medieval battlefield. If dismounted or robbed of his sword, then a knight needed to be handy with an axe, mace or, the weapon of last resort, a dagger.

Swords

The sword was an especially powerful symbol for a medieval knight. It was the weapon used to give him his status as a knight in his initiation ceremony, it had usually been blessed by a priest, and the shape of the blade and handle was often used as a crucifix for prayer. Despite this romantic symbolism, iron and steel swords were lethal weapons; long, heavy, and sharp, they could easily sever a limb with one blow. Up to the late 10th century CE, sword blades tended to be lighter and a little shorter than those from the 11th century CE onwards. The design remained remarkably stable with only a slight shortening of the blade by the 13th century CE, and an increase in length again in the following century, but even then individuals wielded the weapon of their choice. The medieval longsword used by knights may be categorised into six general types, each with their own variations in dimensions, but all meant to both thrust and cut:

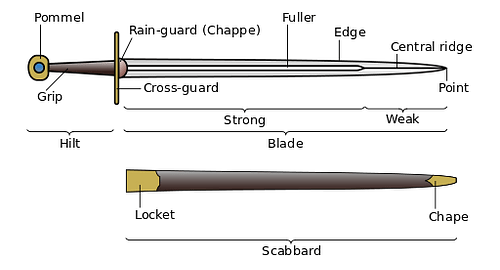

- Double-edged and tapering to a point. A channel (fuller) down the centre on both sides made it lighter. The blade could be up to 1 metre (40 inches) in length. These longswords were known as 'great swords' or 'swords of war' and were designed to be swung using both hands on the grip.

- Double-edged with a more pronounced tapering. A channel running only three-quarters of the length of the blade. This was the most common longsword up to the late 13th century CE.

- A longer and broader blade which widened slightly towards the handle. A channel ran down about half of the blade. The blade measured around 1 metre (40 inches), the grip averaged 15-23 cm (6-9 inches). In use from c. 1240 CE, they had the colourful later name of hand-and-a-half swords or 'bastards'.

- A short wide-bladed sword primarily used for slashing but still with a tapering point. The channel ran halfway down the blade.

- A blade with a flattened diamond cross-section and a pronounced tapering and point. In use from c. 1280 CE, it had only a short 16 cm (4 inch) grip and was designed to pierce plate armour. Such thrusting swords often had no sharpened edge near the hilt so that a knight could safely grasp it to increase the power of the thrust.

- A blade with a double channel near the hilt and then a single channel or with a raised rib. Both types were used in the 15th century CE. These types were made in mainland Europe where centres such as Milan and Cologne gained a reputation for quality. Another continental innovation which spread to England was a finger ring in the handle for the forefinger which provided better grip.

The pommels of swords were as varied as their blade designs, but the flat disc form predominated. They could be plain, have a pronounced centre or even have petals. Alternatives up to the 13th century CE were the diamond shape, sphere, and the 'cocked hat' common to Viking swords. In the 14th century CE, a 'scent-stopper' variety became common which was a bulbous decorative addition.

Cross-guards to protect the hand were generally plain, sometimes they curved slightly away from the handle which was typically covered with two pieces of wood, bone, or horn wrapped around the metal tang and bound with leather or silk cords. In the 14th century CE, a hole was bored through a single piece of the grip material and slotted over the tang.

The richer and more flamboyant knight might add a bit of bling by using gold or silver wire on the handle. When not in active use the sword was kept in a leather and wood scabbard which might have iron fittings at the top and base. Some swords had a small flap of leather (chappe) attached to the handle so that when the sword was in its scabbard rainwater did not enter and rust the blade. Given the length of swords, a complex arrangement of straps and belt was required to ensure they did not trip up the knight and yet could be drawn easily. By the 15th century CE, the fully diagonal sword belt had become common. Belts were another opportunity for a knight to add some sparkly bits to his overall attire, especially via metal eyelets and bars.

Alternatives to the long straight blade were the falchion with a short but broad curved blade, or sometimes with one edge curved and the other straight, which had a cutting edge on the outer side. Seen from the 13th century CE, these wicked-looking weapons were specially weighted with a thicker blade towards the tip which made them excellent at chopping off an opponents extremities. Most knights would have also carried the extra insurance of a dagger, which usually resembled a miniature version of the longsword but only had one edge sharpened. By the 15th century CE, the two most common types were the rondel dagger with two circles at either end of the handle and the ballock dagger which had two swellings between the handle and blade; both types had long tapering blades.

Lances

One of the chief characteristics of the medieval knight was that he rode a horse, and one of the most effective weapons to strike down an opponent before he got too close for comfort was the lance. Knights practised long and hard at jousting, and the medieval tournament, although it later became a spectacle of chivalry and pageantry, was the perfect place to learn the skills needed to stay alive for longer on the battlefield. Skill at guiding one's horse while one hand carried a lance and the other a shield, maintaining balance in the saddle, striking a moving target, and staying on the horse in the case of receiving a body-blow were all necessary for survival.

Lances, from around 2.4 to even 3 metres (8-10 ft) in length, were commonly made of ash or cypress and had a steel tip nailed onto the shaft. It was only from the 14th century CE that a vamplate, first circular and then conical, was added to protect the hand carrying the lance. In the 15th century CE the lance was made thinner where the hand gripped it. A leather strap might be worn around the upper arm to prevent the lance sliding backwards when striking an opponent. By the end of the 14th century CE, knights were wearing a lance rest as part of the breast armour to give the weapon additional stability.

Maces

Maces became popular as armour improved and became more resistant to a slashing sword. The shaft was made of wood and, in early versions, the head was of a copper-alloy which had protrusions made by using a mould - either rounded projections or flanges. The version with a spiked ball was known as a 'morning-star'. In the 14th century CE, the head was commonly made of steel or iron. To make sure the mace was not lost after a particularly heavy blow, a strap was worn around the wrist and attached to the base of the shaft. In the 13th century CE there developed the flail - a shaft with a metal spiked ball attached via a chain. A favourite of movie-makers and weapons collectors, it was not a commonly used weapon on the battlefield.

Axes

Some knights used an axe, which typically had either a flaring blade and very long shaft (like a classic woodcutter's axe) or a thinner, more pointed blade with a short shaft (like a modern firefighter's axe). Sometimes either axe type was fitted with a spike at the end of the handle and, in later 14th century CE versions, a top spike. The same century saw further developments such as the use of hammers and the poleaxe (aka pollaxe) which was a combination of hammer and axe with a spike; some of these had a very pointed axe blade and so were known as a ravensbill. An axe on a very long shaft with a top spike was known as a halberd. Another variation of the axe was the glaive, which had a long and slightly convex blade attached vertically to a long wooden shaft, but these were more commonly used by foot soldiers.