Elephants were used in the ancient Indian army, irrespective of regions, dynasties, or points in time; their importance was never denied and continued well into the medieval period as well. The ready availability in the subcontinent of the Indian elephant (Elephas maximus indicus), one of the three recognized subspecies of the Asian elephant and native to mainland Asia, led to its gradual taming and use in both peace and war. Capable of fulfilling a variety of military functions, the most important of which was the psychological impact it could cause, nonetheless, the elephant was both a boon and a bane. Despite the defects, the ancient Indians continued to believe in their efficacy even when the ground results showed otherwise. One main reason was the concept of military prowess associated with possessing and employing these huge beasts.

The elephant on the battlefield

Virtually every ruler in India possessed elephants and used them to further his own ambitions. These included:

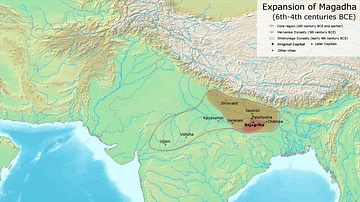

- kings belonging to various dynasties ruling Magadha (6th century BCE to 4th century BCE)

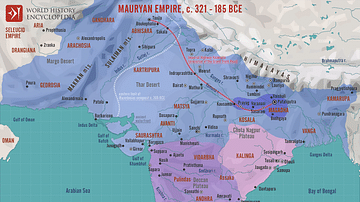

- dynasties of the Mauryas (4th century BCE to 2nd century BCE)

- Guptas (3rd century CE to 6th century CE)

- Pallavas (3rd century CE to 9th century CE)

- Cholas (4th century BCE to 13th century CE)

- Rashtrakutas (8th century CE to 10th century CE)

- Chalukyas of Vatapi (6th century CE to 8th century CE)

- Western Chalukyas of Kalyani (10th century CE to 12th century CE)

- Palas (8th century CE to 12th century CE).

In ancient India, initially, the army was fourfold (chaturanga), consisting of infantry, cavalry, elephants and chariots. While the chariots eventually fell into disuse, the other three arms continued to be valued. Of these, the elephants had a prime place. The elephant corps was deployed in a battle in a block or a line, as per the overall army formation (vyuha) decided upon by the commanders. The Mahabharata mentions the use of elephants in battle, though secondary to the chariots which were the preferred vehicle of the warriors, especially the elite ones. King Bimbisara (c. 543 BCE), who began the expansion of the Magadhan kingdom, relied heavily on his war elephants. The Nandas of Magadha (mid-4th century BCE - 321 BCE) had about 3,000 elephants. The Mauryan and Gupta empires also had elephant divisions; Chandragupta Maurya (321-297 BCE), had about 9,000 elephants. The army of the Palas was noted for its huge elephant corps, with estimates ranging from 5,000 to 50,000.

Each kingdom had its own elephant corps headed by a commander or superintendent. In the Mauryan Empire, where the 30-member war office was made up of six boards, the sixth board looked after the elephants, which were headed by the gajadhyaksha. The Gupta elephant commander was known as the mahapilupati. In some cases, however, the cavalry and elephants belonged to a single division as in the case of the Western Chalukyas of Kalyani (present-day Basavakalyan, Karnataka state), where the officer in charge bore the combined title of kari-turaga (patta) sahini. In his work Manasollasa, the Kalyani Chalukya king Someshvara III (1126 CE-1138 CE) states that the general (senapati) should be an expert in riding both horses and elephants.

A lot of attention was given to the capture, training, and upkeep of the elephants. Many treatises were written on these subjects, and many important works of the ancient period, like the Arthashastra of Kautilya (c. 4th century BCE), give a lot of information on different kinds of elephants, breeding, training, and their conduct in war. The Buddhist Nikaya texts mention that the royal elephant should be trained to tolerate blows from all kinds of weapons, protect its royal rider, go wherever commanded to, and be able to destroy enemy elephants, infantry, chariots, and horses. The elephant was supposed to engage in battle with its trunk, tusks, legs, head, ears, and even its tail.

The importance of elephants, especially royal ones, can be gauged from the fact that in the Harshacharita, the biography of his patron Emperor Harshavardhana (606–647 CE) of Sthanishvara (modern Thanesar, Haryana state), the author Banabhatta (c. 7th century CE) devotes many pages to describing the elephants possessed by his master and, in particular, his favourite war elephant named Darpashata who is described as the emperor's “external heart, his very self in another birth, his vital airs gone outside from him, his friend in battle and in sport, rightly named Darpashata, a lord of elephants” (Banabhatta, 52). Banabhatta further states that an elephant provides protection like a hill fort (giridurga), but with the advantage of being mobile (sanchari). It is formidable with tower-like high temple bones (kumbhakuta), i.e. resembles a hill fort, which is formidable with kutas (sloping earthen mounds at the gate). Also, the elephant was strong and dark like an iron rampart (prakarah) and served to protect the earth akin to a rampart.

Strategic & tactical uses

The main use of the elephant was for its routing ability; at one sweep it could get rid of a number of enemy foot soldiers, scare away horses, and trample chariots. Thus, it was also about the psychological impact it could have, i.e. the shock value. The enemy forces would be scattered, leading to a breach of formation, which could then be exploited. The possession of a number of elephants added to the ruler's prestige and was believed to create a psychological effect on his enemy's minds, who could be thus be prompted not to challenge him or to submit.

The practice of intoxicating elephants was resorted to as it brought out the ferocious nature of the animals, which increased their capacity to wreak destruction on the enemy troops. An inebriated elephant could cause much more panic and thus break enemy formations, especially of infantry, by trampling them mercilessly. The Chalukyas of Vatapi (present-day Badami, Kanataka state) were well known for their use of drunken elephants manned by equally (or less) drunken warriors, which caused the enemy to retreat within the walls of his capital. The idea behind employing both drunken men and animals was to make them attack en masse and thus trample everything down without much thought, causing panic and loss of both morale and enemy numbers. In the words of historian John Keay, because of “his champions and their punch-drunk elephants” (Keay, 170), the Chalukya king could afford to treat his neighbours with contempt.

Besides actual field deployment, the elephants carried out many functions. These included clearing the way for marches, fording the rivers that lay in their paths, guarding the army's front, flanks, and rear, and battering down the walls of the enemy.

The elephants were also used as command vehicles, i.e. the preferred mount of the commander enabling him to have a commanding view of the battlefield. The kings and princes were supposed to be well-trained in handling war elephants. The Buddhist texts mention some such royals like the Kuru king and thus show that in the 6th and 5th centuries BCE such trends were prevalent. The princes of the Western Ganga Kingdom (4th century CE - 11th century CE) were also similarly well-trained, and some of them even wrote treatises on the science of elephant management.

War elephants were also seen as prized booty; the historical instances are replete with the victors capturing the enemy war elephants after a battle, as Prasenajit (c. 6th century BCE) of Koshala did after defeating King Ajatashatru (492 BCE to 460 BCE) of Magadha, for example. Invaders could also be thus bought off, and the invasion thus stalled; the Rashtrakuta emperor Dhruva Dharavarsha (780-793 CE) abandoned his attack on the Pallava Kingdom after he was offered an indemnity of war elephants.

Arms, armour & riders

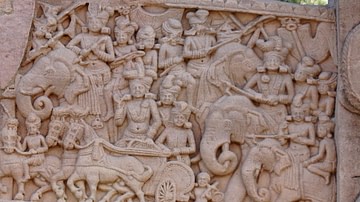

According to the Mahabharata, the elephants were provided with armour, girths, blankets, neck ropes and bells, hooks and quivers, banners and standards, yantras (possibly stone-or-arrow-hurling contrivances) and lances. The riders were seven: two carried hooks, two were archers, two were swordsmen, and the last one had a lance and a banner. In the 6th and 5th centuries BCE, the elephants carried rugs on their backs, called hatthatthara in the Buddhist Pali works. The Mauryans used three riders, all archers, with two shooting from the front and the third from the back, as can be seen from the sculptures at the Sanchi stupa and in the frescoes of the Ajanta caves.

While the riders initially used both missile and short arm weapons, from the Gupta period onwards, the main weapon seems to have been the bow. The elephant driver was called as ankushadhara (Sanskrit: “holder of the hook”) as he carried the ankusha or a two-pointed hook or goad to control the elephant. The elephants continued to be decorated with ornaments.

Drawbacks

Despite all the training, the elephant could not be taught to override its moody nature; it remained ungovernable, and this nature showed when the elephant was either too wounded or prompted to anger. In such cases, the elephants did more harm than good; they trampled their own troops, ran amok, and could even carry the commanders riding them away from the battlefield, which could be interpreted as flight, making their soldiers panic and flee, or simply give up the fight.

In the Battle of Hydaspes (326 BCE), King Porus (Sanskrit: Puru or Paurava; Greek: Poros) (c. 4th century BCE) staked everything on his elephants to defeat the Macedonians being personally led by Alexander the Great (356-323 BCE). His 200 elephants were posted along the front of the infantry, like bastions, in order to scare away the enemy. Alexander, however, proved to be more than a match. He focused on destroying the other arms posted at the flanks. As the Indian cavalry, infantry, and chariots were gradually routed, the elephants though managing to cause initial havoc, went berserk due to their wounds inflicted by the enemy and trampled anyone they could find, which, in this case, were mostly the Indians themselves. Porus thus lost many of his numbers; himself fighting on an elephant, he also got wounded and was taken prisoner.

The situation did not change with time. Astute commanders continued to challenge the use of elephants as battle-winners as well as their rivals' skills in elephantology (gajashastra). Dhruva Dharavarsha defeated and captured the Western Ganga ruler Shivamara (788-812/16 CE), the author of a treatise on war elephants (the Gajashataka). The Kalyani Chalukya king Vikramaditya VI (1076–1126) steadied his troops and won the day against his brother and rival Jayasimha (c. 11 century CE), whose elephant corps had brought about an initial success in the battle.

When using the elephant as a command vehicle, the commander was a sitting duck and could easily be targeted by enemy soldiers; his death or falling from the seat (howdah) would create undue panic and turn the tables. In many cases, the royal elephant was expressly targeted for this reason. In one instance, at the Battle of Takkolam (949 CE), the Chola crown prince Rajaditya (c. 10th century CE) was attacked by the enemy; his elephant was killed, the enemy got into his howdah and killed him then and there. The disheartened Chola army fled in disorder, leaving their opponents, the Rashtrakutas, victorious. Thus, the elephant did not exactly provide protection to a commander; the rider(s) remained vulnerable. In the Battle of Koppam (1052/54 CE), the Chola prince Rajendra (1052/54-1063 CE) killed many of the enemy warriors who had mounted his elephant after first showering it with a rain of arrows, while his brother, the Chola king Rajadhiraja (1044-1052/54 CE), died of mortal wounds inflicted when his elephant was similarly assaulted.

Legacy

The overemphasis on elephants led to heavy reliance on them through the course of ancient, and even medieval Indian history. The Turkic and later the Mughal invaders too adopted the use of elephants once they had established kingdoms in India. However, the increasing employment of horse archers, firearms, and later artillery, made the elephants redundant as an effective field force.

The elephants thus did not leave much of a legacy—part of a particular military system developed by the ancient Indians, they could not cope with, let alone counter, different styles of warfare brought in by different invaders at different periods of time, which included ultimately the European infantry and artillery-based warfare of the 17th and 18th centuries CE. The very nature of the elephant, being resentful of too much control and discipline and revolting when too hard-pressed, implied that the elephant corps could never be drilled to the same level of efficiency as the infantry and cavalry. To make matters worse, out-of-control elephants caused much more damage (again due to their size and power) to their own side than other arms in similar panic.

The Indian rulers and military thinkers of the ancient period nonetheless felt that a strong initial elephant charge could break the enemy morale and formation and thus pave the way for other arms to move towards victory. However, able generals could easily outwit elephant experts, outmanoeuvre the elephant corps and blunt the initial shock and awe, which they did all through the course of ancient Indian history.