English medieval knights wore metal armour of iron or steel to protect themselves from archers and the long swords of opponents. From the 9th century CE, chain mail suits gave protection and freedom of movement until solid plate armour became more common in the 14th century CE. A crested helmet, shield with a striking coat of arms, and a liveried horse completed a costly outfit which was designed to both protect and intimidate. Such was the mesmerising effect of a fully suited-up knight that armour continued to be worn despite the arrival of gunpowder weapons and remained a favourite costume of the nobility when posing for their oil painting portraits well into the modern era.

Armour pieces have survived from the medieval period, and besides these, historians rely on descriptions in contemporary texts, illustrations, and the stone tombs of knights which were frequently topped by a life-size carving of the deceased (effigy) in full battledress. Knights had to provide their own armour, but sometimes a sovereign or baron under which they served did give them either a whole or a piece of armour. There are records, too, of sovereigns replacing armour damaged in battle. The cash-strapped knight could also hire a suit of armour or, at a push, win a suit by defeating an opponent either at a medieval tournament or in battle itself. Armour had to be regularly cared for, and it was usually the duty of a knight's squire to clean and polish it. Chain mail was cleaned by swirling the armour around a barrel full of sand and vinegar; squires must have been as relieved to see the advent of smooth plate armour as the blacksmiths who had spent untold hours of tedium forging tiny metal rings into a coat of chain mail. Armour lasted well into the age of firearms from the 15th century CE and was even tested against bullets fired at close range but the age of the knight was by then nearly over, soon to be replaced by the cheaper-to-equip soldier who needed far less skill in firing guns and canons.

Chain Mail

Chain mail armour was commonly used by knights from the 9th up to the late 13th century CE, although it did continue to be worn into the 15th century CE, often under plate armour. It was made from hundreds of small interlinking iron rings additionally held together by rivets so that the armour followed the contours of the body. A hooded coat, trousers, gloves, and shoes could all be made from mail and so cover the entire body of the knight except the face. The coat, which often hung down to the knees, was known as a hauberk. The arms included mittens (mufflers) which could be passed over the exterior of the hands; alternatively, mail or metal plate and leather gauntlets were worn (from the 14th century CE). The hauberk had leather laces at key points such as the neck to make it a snug fit and ensure no flesh was left exposed. The hood part, padded or lined on the inside or worn with a cap for comfort, was pulled over the head with sometimes a ventail which could be fastened across the mouth. Under the mail coat, extra protection and comfort were provided by a padded tunic (aketon, wambais or pourpoint) made from a double layer of cotton stuffed with wool or more cotton.

The mail trousers, worn over leggings for comfort, usually had the shoes incorporated, often with a leather sole for better grip. An alternative to full trousers was to wear stockings or mail which only covered the front parts of the legs and the top of the foot and which were tied behind using leather laces. Another option was mail socks or a padded leather roll over the thigh (gamboised cuisse). The knee might have an extra protective disk (genouillier or poleyn) attached to the mail, and the elbows, too, although more rarely. Shins were particularly vulnerable when a knight was mounted on his horse, and so extra metal plates (schynbalds) might be worn on top of the mail.

Over everything, a cloth surcoat (silk for the wealthy) might be worn, which was typically sleeveless. Going down to the knees or feet, split at the front and rear and tied with a belt, it allowed the knight to display his coat of arms or those of his leader. However, many surcoats were of a plain colour, so their precise function is not clear. They may have helped protect the armour from rain or the heat of the sun.

The mail suit was heavy at around 13.5 kilograms (30 pounds) but not excessively so. The weight was predominantly on the shoulders but could be lessened by wearing a belt. Some were also made lighter by having a shorter cut, especially at the arms and front. Mail armour might have stopped sword slashes, but it did nothing to stop arrows fired at close range or prevent heavy bruising and broken bones. In addition, if the links were smashed into a wound, then blood poisoning was a real danger.

Plate Armour

Plate armour evolved from chain mail with various intermediary styles of armour being worn from the mid-13th century CE. A coat of plates, for example, was a simple poncho of large rectangular metal plates tied with a belt. These and simple chest and back plates could be worn in addition to a mail coat. Scale armour made from small overlapping pieces of iron attached to a cloth or leather backing like fish scales were worn but were rare amongst European knights. A variation was 'penny plate' armour which was made up of small disks held together by rivets through the centre of each piece.

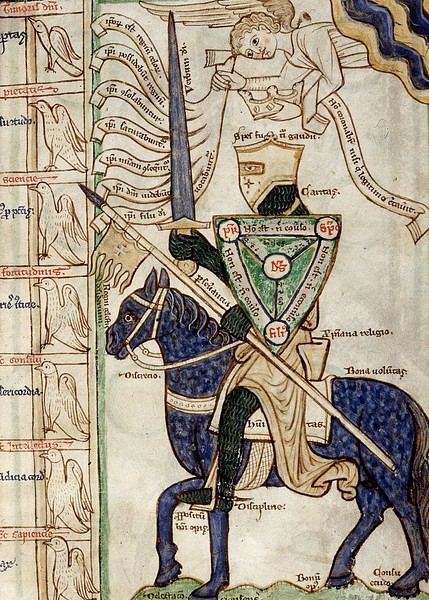

By the second quarter of the 14th century CE, many knights were now wearing steel plate armour on top of chain mail. The breastplate became more common from the mid-14th century CE. Curved and sometimes with an arrangement of flexible strips or hoops of metal at the waist (fauld), they were attached using straps, buckles or semicircular rivets. A simpler backplate might also be worn, which was attached to the front plate via hinges. Greaves covering the whole of the leg became common as well as a plate (sabaton) or metal scales covering the top of the foot. Knees were often now completely enclosed in metal with a circular or oval wing at the side to deflect blows. The cuisse to protect the upper legs was now also made of plate metal, usually with a ridge or stop-rib which prevented the point of a sword sliding up the leg. Arms were protected like the legs, with a circular addition for the elbow and sometimes a wing at the shoulder (spaudler), again to deflect blows. Tubular arm plating was known as a vambrace. A circular disk (besagew) in front of the armpit protected the exposed area between the arm and chest plates. An alternative was the pauldron, a plate which wrapped around the entire shoulder.

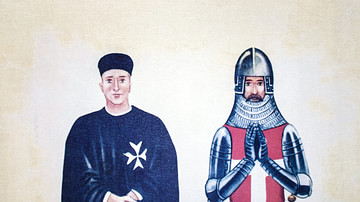

From the second quarter of the 15th century CE, the typical knight was covered from head to foot in steel or iron plate armour which followed the contours of the body more closely. Replacing the undercoat of chain mail, was a more comfortable padded clothing with some short pieces of mail at such exposed parts as the under and inner arms. (an arming doublet). It was now rare for a knight to wear a surcoat or jupon over the gleaming armour.

The various plates of armour were held together using laces (points), straps, and hinges. The neck was now enclosed in an all-metal circular plate (gorget), and gauntlets returned to the mittens of earlier centuries and had wide conical cuffs in steel. The armour was so efficiently made that it took only about 10 minutes for two squires to dress a knight for combat. Contrary to knights depicted in some films, it was not necessary to use a crane to get a knight on his horse, and he was not a defenceless and upturned insect if he fell off it. A full suit of armour weighed from 20 to 25 kilograms (45-55 lbs) - less than a modern infantryman would carry in equipment - and it was distributed evenly over the body so that a knight could move with some freedom. The greatest threat remained heat exhaustion from fighting in hot weather as ventilation was poor. In addition, armour was still not capable of stopping such arrows as the bodkin with a long head and no barbs.

Helmets

The helmet, or helm as it is often called, was necessary to protect the face and head in general. Conical helmets were made from a single sheet of steel or iron, sometimes with interior bands for extra strength. From around 1200 CE helmets became more sophisticated and were made from cylinders of metal with a protective strip for the nose or full face mask. Some versions had neck guards. By the mid-13th century CE, the full helmet which enclosed the whole head was more common, which had a single horizontal slit for vision. Such helmets were reinforced by adding extra vertical strips of metal and the flat-top design was popular, even if it offered less protection from a blow than a conical top. A simple iron skull cap was an alternative and known as a bastinet or cervellière at this time. By the start of the 14th century CE, helmets had reacquired their conical tops, they extended lower down the neck, and visors were added which could be removed if preferred. This type is also called a bastinet.

For greater comfort, helmets were lined and padded with leather and horsehair, grass, or similar material. Straps inside the helmet and a scalloped lining at the top pulled together by a drawstring allowed it to be adjusted so that the slit in the visor was at the correct height for the wearer. Another strap for the chin kept the helmet in place. Ventilation holes were added to the lower front part to facilitate breathing. From around 1330 CE, visors protruded from the helmet like a snout to further increase the ventilation. Some helmets had a plate (bevor) hanging down to protect the throat. Another type, not common to knights but still a choice for some, was the kettle hat - a conical helmet with a wide brim.

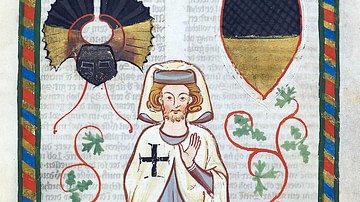

The helmet could be decorated by making patterns and designs of the ventilation holes or such additions as feathers (peacock and pheasant were most impressive) and even painted. By the end of the 13th century CE, crests were common. Made from metal, wood, leather or bone, they could be a simple fan shape or represent three-dimensional figures. Those helmets used in medieval tournaments were generally the most extravagant and probably not used on the battlefield. By the 15th century CE, helmets were much less showy, although a single plume might be worn by the more fashionably daring knight.

Shields

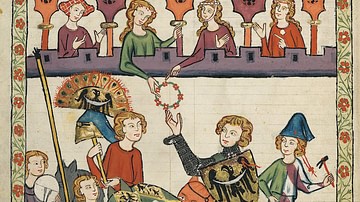

The first shields for knights were of the long kite shape made famous by the Normans; these then reduced in size over time to become the classic straight top edge and tapering lower edges towards a point type of shield familiar in heraldry. Shields were made from wooden planks covered with leather or thick parchment on both sides. They were the perfect place to display the coat of arms of one's family and so were frequently painted. Shields were probably about 1.5 cm (0.6 in) thick, but the lack of surviving battle specimens makes materials and dimensions difficult to ascertain. Shields were carried using three straps (brases or enarmes) riveted to the inside, and a pad cushioned any blows against the carrying arm. A fourth strap, a guige, was used so that the shield could be hung down one's back from around the neck when not required. A concave rectangular shield appeared from the mid-14th century CE, which had edges curving outwards. By the end of the same century, though, shields were primarily used in tournaments as the presence of plate armour made them unnecessary and cumbersome in battle. A less common alternative to the large shield was a small circular shield of wood, a buckler, which had a central metal boss and a single hand grip.

Additional Armour & Embellishments

Some effigies show a knight wearing what appears to be a stiffened leather neck protection. Just such a figure can be seen in a knight's tomb in Wells Cathedral, England, c. 1230 CE. An alternative form of neck protection was to wear an aventail or mail curtain which hung from the back of the helmet. Gauntlets were to protect the hands, of course, but some were fitted with knuckleduster metal spikes (gadlings) to make them into bruising weapons in themselves.

Armour was decorated, by those who could afford the process, with embossed designs, sometimes of the wearer's coat of arms, for example. Crusader knights sometimes wore a three-dimensional cross on each shoulder while another avenue for symbolic and heraldic display, besides the shield, was the small shoulder boards known as aillettes. As these latter additions were likely made of parchment, wood, or leather, according to some descriptions, they probably served no purpose as actual armour and were not common after c. 1350 CE.

Not to be forgotten is the knight's horse. Again, a good place for armorial display, they sometimes wore a cloth caparison which might also enclose the animal's head and ears. Other options, which better protected the horse, were a two-piece coat of chain mail (one for the front and the other hung behind the saddle), a padded helmet (testier), a plate head covering (shaffron), or an armour plate of metal or boiled leather to protect the chest (peytral).