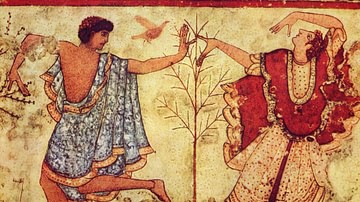

As in just about any other period of history, clothing in the Middle Ages was worn for necessity, comfort, and display. Bright colours and rich decorations made for a striking medieval wardrobe, at least among the wealthy, although there was a surprising similarity in clothes for different social classes and the sexes. More expensive items of clothing were generally distinguished not by their design but by their use of superior materials and the cut. Governments sometimes intervened in who should wear what and how much certain items were taxed while some members of the clergy, in particular, were frequently berated for looking rather too flashy and being indistinguishable from knights. Trends came and went, as today, with laces sometimes in vogue, pointed shoes became the done thing, and tunics were made ever shorter towards the end of the period when showing a little more leg was considered the height of fashion (and that was just the men).

Materials & Colours

Clothes were generally the same for all classes but with the important difference of extra decoration, more and finer materials used, and an improved cut for the wealthier. Additions of metal, jewels, and fur, or intricate embroidery also distinguished the wardrobe of the rich from that of the poor. Outer clothes were not so different between the sexes either except that those for men were shorter and the sleeves roomier. As all clothes were tailor-made, a good fit was guaranteed.

Clothing was usually made from wool, although silk and brocade items might be saved for special occasions. Outer clothing made from goat or even camel hair kept the rich warm in winter. Fur was an obvious way to improve insulation and provide decorative trimmings, the most common were rabbit, lambskin, beaver, fox, otter, squirrel, ermine, and sable (the latter three became a standard background design in medieval heraldry such was their common use). More decoration was achieved by adding tassels, fringes, feathers, and embroidered designs, while more expensive additions included precious metal stitching and buttons, pearls, and cabochons of glass or semi-precious stones. The taste for colours was the brighter the better, with crimson, blue, yellow, green and purple being the most popular choices in all types of clothes.

Underclothes

Nightwear was not much of a social indicator and did not take a whole lot of forethought as most people slept naked. After a quick wash with cold water in a basin the first thing to put on in the morning, at least for the wealthier members of society, were underclothes, usually made of linen - long-sleeved shirts and drawers for men (down to the knee or below and known as braies) and a long chemise for women.

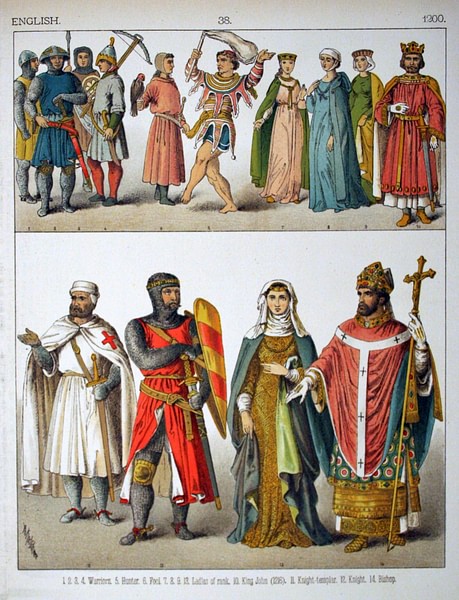

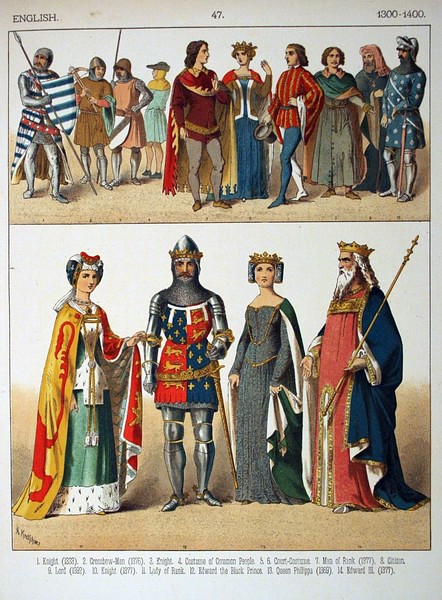

Both sexes wore long-sleeved tunics which had either a low-cut neck or a slit down the front so they could be put on over the head and then tied at the neck, sometimes with a brooch. The tunic might go down to the knee or even the ankles in the case of more formal wear for the nobility. The longer versions were usually split up to the waist at the front and back. Most tunics were made in one colour, although they might have a different coloured lining. Decorative embroidery was most often added at the neck, cuffs and hem, less often on the upper arms or all over the garment. A 14th century CE fashion was the jupon or pourpoint, a tight tunic or jacket with padding. The jupon was fastened by buttons or laces all down the front and there were sometimes buttons running from the elbow to the wrist; sleeves sometimes reached down to the knuckles on these garments.

Outer clothes

On top of the first tunic, another tunic was worn but either without sleeves or with much baggier sleeves; it was also shorter at the waist than the undertunic. For colder weather, these top tunics were often lined with fur (then called a pelisson). A waist belt with decorative metal buckle was worn over the tunic and was the flashiest part of a man's wardrobe, very often with gold, silver, and jewelled additions.

An alternative type of outer tunic was the tabard, cut like a poncho but with the sides closed by stitching or clasps. Heralds wore a version of the tabard with sleeves only covering the outer arms and the chest decorated with the coat of arms of the noble they represented. Once again, the 14th century CE saw a new fashion, that of the cote-hardie, a tight jacket with sleeves going only to the elbows, and buttons or laces from the neck right down to the waist (laces were especially fashionable in the 12th century CE). Tied with a belt, the part below the waist billowed out like a skirt, sometimes with a dagged hem. Over time hanging cuffs were added to the sleeves which became longer and a collar was added.

Noble women wore fine dresses, particularly at court and at such social events as the medieval tournament. In contrast to later more romantic paintings, illustrations from the Middle Ages often show quite plain dresses with only a minimal decoration. Typically of a single colour (sometimes with a different coloured lining), they are long, long-sleeved, high-cut, and close-fitting above a belted waist. Women's belts, almost ever-present in graves and illustrations, sometimes had chains hanging down (chatelaine) to which were attached small decorative objects (for working women these would have been small tools, useful for such tasks as weaving and embroidery). The most common extra decoration is a border at the cuffs and neckline. of the dress. Illustrations often show tall pointed or flat-topped hats being worn with veils hanging down, although not covering the face.

Men wore hose or long stockings of wool or linen which went up to the knee or just above it and which were secured to the belt of their drawers. Women's stockings were shorter and held up by a garter worn below the knee. Some stockings ended in a stirrup while those which fully enclosed the foot might have a leather sole added to them. Stockings might also be padded to create a fashionable pronounced point at the toes.

Cloaks & Mantles

For going out, a cloak or mantle was worn, which was typically made from a roughly circular or rectangular piece of cloth which might, too, be fur-lined. Here was another chance for a bit of jewellery as cloaks were fastened with either a chain or brooch at the neck. An alternative fastening was to pull one corner of the cloak through a hole in the other top corner and then tie a knot. A man might fasten his cloak at the left shoulder to allow his right arm to freely draw his sword. An alternative to the cloak was a great coat (garde-corps or herygourd) which stretched down to the shins or ankles and had wide sleeves gathered at the shoulder. Both cloaks and great coats might have a hood with some being fastened using a button. An entirely separate hood which also covered the shoulders was an alternative for headgear. An alternative outer garment from the 14th century CE was the houppelande, a long robe split down the sides from the waist down and with flared sleeves and a high collar.

Gloves, Hats & Footwear

Gloves were worn outdoors and might go almost up to the elbow. They also used fur lining and frequently had embroidered designs, typically a gold band. Hats were worn by everyone. At home, men wore a linen coif (close-fitting cap) which was tied under the chin and decorated with embroidered designs. Women meanwhile wore a wimple (a headdress which also covers the neck and sides of the face). Keeping on their indoor headgear, a cap or hood was worn as well when outdoors or, when travelling, a hat with a brim that could be turned up at either the back or front. Some hats had a soft and shapeless crown, others were round or had a flat top, and all types could easily be decorated with a couple of ostrich or peacock feathers. From the 14th century CE, hat bands came into fashion.

Boots, usually quite loose in fitting, were either high riding boots or low on the leg (bushkins). Shoes covering the ankle were worn out of doors, and soft slip-on slippers in one's private chambers. Shoes, made from cloth or leather, were closed via inner laces, a strap or buckle, which was another opportunity for decoration and personalisation. Footwear became increasingly pointed as the Middle Ages wore on, especially for men.

Maintenance

For the aristocracy, there was no worry over the maintenance of their wardrobe as that was done by their staff. The chamberlain was (before the role widened and became more important) responsible for his master's wardrobe which was kept folded in chests or on pegs ('perches') when not in use. Ladies had their ladies-in-waiting and maids to help them dress. Washing was done by laundresses who soaked the clothes, or at least the less delicate smalls, in tubs of water mixed with caustic soda and wood ashes, and then pounded them clean using wooden paddles.

Social Display & Control

As already mentioned, there was not such a distinction between the general style of clothes of different classes except in terms of cut and materials. Nevertheless, the distinction was a sharp one, and it was protected by the upper classes, especially when people tried to dress above their station for personal advancement. Various sumptuary laws were passed from the 13th century CE onwards which restricted the wearing of certain materials by the lower classes in order to maintain the class divisions of society. There were even limits put on the quantities of such expensive imported materials as furs and luxury cloths like silk for the same purpose. Another indicator of the relationship between clothing and social status is the fact that clothing was considered along with other items of a person's property to decide their tax obligation, but for the higher classes clothing was often left out, suggesting social display was regarded as a necessity for them and an unnecessary luxury for everyone else.

The clergy was one section of society that had more clothing restrictions than most: nuns could not wear expensive furs, and members of specific monastic orders had to wear a particular style of habit to make themselves easily identifiable. Neither could members of the secular clergy adopt certain wider fashions, notably the 13th-century CE shortening of tunics to show a little more leg or the use of too many colours in one outfit. Although there is evidence these rules were frequently ignored, the idea was to maintain the distinction between the clergy and other members of society, especially knights. There were even measures to distinguish between the faiths, and Jewish clergy, for example, had to wear two white tablets of linen or parchment on their chests from the mid-13th century CE.

Access to clothing was also restricted in times of economic strife during wars like the Hundred Years War with France (1337-1453 CE), presumably to stop wasteful spending. At such times governments, in effect, rationed clothing so that, for example, priests might only be permitted one new robe per year and bishops three. The same rules applied to aristocratic ladies and knights who could only have one new change of outfit per year. For the staff in the employ of a local baron or castle-owner, there were differences in the cost, cloth, and colours of the clothes their lord provided them so that there were marked distinctions between such groups as the menial servants, squires, clerks, men-at-arms, and sergeants.

Clothing remained an important and easily communicated method to display rank and job title. On the battlefield, knights wore chain mail or plate armour with a dash of colour perhaps provided by a surcoat and plumed helmet, but they still had to look the part of society's ambassadors of chivalry even when at leisure. Particular robes were worn on special occasions by those with the privileged right to wear them. For example, members of particular knights orders such as the Order of the Garter could wear a fine dark blue robe with a gold collar-chain made up of knots and red roses encircled with garters. Clearly, then, there were subtle and not so subtle wardrobe distinctions, not only between certain classes but also within the same class in a continuous game of social display emphasising just who had the right and the means to wear what and when.