The siege of Antioch in 1097-1098 CE occurred during the First Crusade (1095-1102 CE) when the western Crusader knights were on their way to retake Jerusalem. The great metropolis of Antioch in northern Syria was heavily fortified, and it would take eight months and a slice of treachery to finally break into the city. Even then the Crusaders had to defeat a huge Muslim relief army, and the difficulties of its capture, the tales of divine visions, holy relics, famine and fortitude made the siege of Antioch one of the most recounted stories of all the medieval crusades.

Prologue

The First Crusade was conceived by Pope Urban II (r. 1088-1099 CE) following an appeal from the Byzantine emperor Alexios I Komnenos (r. 1081-1118 CE) who wanted to fight back against the expanding Muslim Seljuk Turks who had robbed the Byzantine Empire of a good portion of Asia Minor. The fact that Jerusalem, the holiest city in Christendom, had also fallen, proved a great motivator for knights to travel from all over Europe and try to retake it. Initially, the mixed force of Crusaders and Byzantines enjoyed success, notably recapturing Nicaea in June 1097 CE and winning a great victory at Dorylaion on 1 July 1097 CE. The Crusader-Byzantine army then split up in September 1097 CE, with one army moving on to Edessa further to the east and another into Cilicia to the south-east. The main body headed for Antioch in Syria, the key to the Euphrates frontier.

Although it had lost a little lustre to local rival Aleppo since the 6th century CE, the great city of Antioch had a glittering history going back to Hellenistic times and was one of the five patriarchal seats of the Christian church. It was also once home to Saint Paul and Peter, and the probable birthplace of Saint Luke. Retaking Antioch after 100 years of Muslim rule, then, would be a boost for everyone and help ensure that further territorial victories to the south would remain permanent ones.

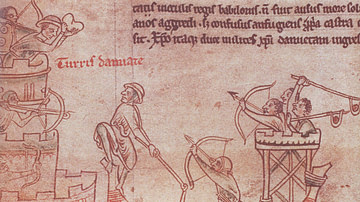

Fortress Antioch

Located on the Orontes River, 19 km (12 miles) from the coast, Antioch had a population of around 40,000 and was enclosed within high walls put in place by the Byzantines in the 10th century CE. The sprawling city was far too big and the terrain too difficult for it to be encircled by a besieging army. At the same time, the city's walls were so extensive that the defenders could not adequately police them. In any case, the most important fortress in Syria could not simply be bypassed as the Crusader's rear would then be exposed to attack. The city had to be taken.

The governor of Antioch was Yaghi-Siyan, and he ruled over a mixed population of Christians, Greeks, Armenians, and Syrians. The Muslims had been tolerant of the large Christian community, permitting the patriarch to keep his position and not converting the major churches into mosques. When news came of the approaching Crusader army, though, the patriarch was imprisoned and many leading Christian figures expelled from the city. Yaghi-Siyan appealed to the Seljuk-ruled cities of Damascus and Mosul for help, and both promised to send relief forces. The sultans in Baghdad and Persia also promised support. It seemed that, as he already had a plentiful supply of water within the city and 6-7,000 armed men, if Yaghi-Sivan could gather enough supplies, he would be able to rely on the city's fortifications and await reinforcements.

On 20 October 1097 CE the Crusader army, numbering some 30,000 men, captured the vital fortified bridge over the Orontes and even rounded up a convoy of supplies on its way to Antioch. It was a good start, and the next day the army was before the walls of the city. Awed by its size and splendour, the Crusaders must have been concerned to see for themselves that the city was protected by marshes and the river on one side, a mountain ridge on another, and sloping defences which climbed into the mountains on the other two sides. On top of that, the citadel was perched 300 metres (1000 feet) above the lower city. This was going to take a while.

The Siege

With only a small force at his disposal, Yaghi-Sivan preferred not to risk any raiding parties on the attackers, and two weeks passed without much action as the Crusaders organised their positions. The contingents led by the Norman Bohemund of Taranto, Godfrey of Bouillon, the Duke of Lower Lorraine, and Raymond IV (aka Raymond de Saint-Gilles), Count of Toulouse, stationed themselves outside the various main gates of the city. The Crusaders, except Raymond who favoured an immediate assault, preferred to rest their men and perhaps wait for reinforcements, especially from Alexios who might provide a few siege engines. Meanwhile, after the inactivity bolstered the defender's confidence, small sorties were sent out to make minor raids on the Crusader camps. Further good news came that a Muslim relief army was on its way from Damascus.

As winter arrived, Bohemund managed to entice the Muslim garrison at nearby Harenc out into the open where they were wiped out. Shortly after, a fleet of 13 Genoese ships brought the Crusaders men, arms, and supplies. Food was becoming a problem though, and the Crusaders were forced to forage far and wide, exposing themselves to more attacking sorties from the city. In response, a tower was built above Bohemund's camp to better cover the gorge of the Onopnicles. By the end of December it became essential to find a better source of food, and so a large force under the leadership of Bohemund and Robert of Flanders was sent to Hama to find it.

With his spy network supplying him with every new move of the besiegers, Yaghi-Sivan made an attack on one of the Crusader camps. The raid was beaten back to the walls of the city with great loss, but many knights were killed too. Things were not going well elsewhere either. Travelling in two groups, with Bohemund slightly behind Robert's force, the latter bumped into the Muslim relief force from Damascus which surrounded him. Bohemund held back and, just when all looked lost, he attacked the Muslim forces with surprise on his side and defeated them. The Crusaders were obliged, though, to return to Antioch not having fulfilled their mission. The attackers then suffered the misery of weeks of rain and little food; men were now dying of hunger, and desertion was rife. The Crusader army was now down to some 700 knights. To taunt the Christians from the security of their fortifications, the patriarch of Antioch was occasionally dangled from a cage over the city's walls. The Crusaders were not any better, robbing Muslim graves for their valuables. The battle was turning into a particularly nasty one.

In this atmosphere of hardship and discontent, Bohemund made his first move which revealed his own personal ambition to take and then rule Antioch for himself, regardless of any prior promises that Crusader acquisitions would be handed over to the Byzantine emperor. Bohemund began to suggest to anyone who would listen that he intended to withdraw from the siege as he had to attend to his lands in Italy. The Norman only promised to stay if his losses were compensated by awarding him the right to rule Antioch once captured. This was not agreed upon by the Crusader commanders, and Bohemund stayed anyway, biding his time.

Meanwhile, a second Muslim relief force was sent from Aleppo and allied cities, which managed to retake the fortress of Harenc. On hearing the news, Bohemund led the entire force of Crusader knights to attack the newcomers, which drove them, in retreat, back to Aleppo. Yaghi-Sivan had not missed this distraction, though, and he sent a large force out to attack the Crusader infantry still camped outside the city. Unfortunately for the Muslims, the Crusader knights just then returned from their own sortie, and, once more, the defenders withdrew to the safety of the city. All of this activity was not improving the food supply, but help was now coming in greater quantities by ship from Cyprus. Even better, a ship commanded by the Englishman Edgar Atheling brought siege engines and building materials from the emperor on 6 March. When a group of the Crusaders collected these vital materials they were jumped by a Muslim sortie, who managed to get hold of the supplies, but reinforcements arrived from the Christian camps, and up to 1500 Turks were killed.

The Fall

By the 19th of March the attackers had put their new materials to good use and built a fortress tower to better attack a fortified bridge which was still in enemy hands and another tower to cover the one major gate they had not yet managed to block. Both of these access points had allowed the defenders to come and go from the city at will, both to attack the Crusaders and replenish the city's food supplies. Without the risk of sorties, the Crusaders could now acquire their own food unmolested and trade with local merchants who had lost their customers inside the city. The tide was beginning to turn, but then news came of a large Muslim army approaching the city in May. Made up of troops from Mosul, Baghdad, Persia, and Mesopotamia, the arrival of this force at Antioch could wipe out the Crusaders if they did not capture the city and use its defences for their own protection. Time was of the essence.

Fortunately for the Crusaders, the leader of the Muslim relief force, Kerbogha of Mosul, was reluctant to move against the enemy while Edessa was in Crusader hands and posed a potential threat to his right flank. An ineffectual three-week stop at that city gave the Crusaders just enough time to prepare their final assault on Antioch. Unknown to his fellow commanders, Bohemund was negotiating with a traitor in the city, an Armenian named Firouz who was willing to sell his loyalty. With news that Kerbogha's army was back on the march, though, many of the Crusaders decided to flee rather than face destruction, notable amongst the doubters being Stephen of Blois. The timing was unfortunate for the very next day Firouz agreed to allow Bohemund's men into that part of the city's walls which were under his command. Boheumnd now shared the plan with his fellow leaders and all agreed to feign a move away from the city to meet the oncoming Muslim army but then, under darkness, return back and attack the western wall of Antioch where Firouz awaited them. The plan worked perfectly, and 60 of Bohemund's knights scaled the walls and took the north-west towers without resistance. Opening several of the city's gates, the rest of the Crusader army was allowed into the city. Just as in the Muslim capture of the city in 1085 CE, the great fortifications of Antioch had been breached not by force but by treachery.

The city, then, finally fell on 3 June 1098 CE after an incredibly arduous 8-month siege, but it was not the end of the story. The Crusaders slaughtered any Muslims they could find, including women, and even many Christians were butchered in all the confusion. Yaghi-Siyan fled the city through a small gate, but his son, Shams ad-Daula, gathered what troops he could and made for the city's high citadel. Bohemund immediately launched an attack, but it was defeated, and the Norman leader was himself wounded in the action. The rest of the Crusaders, meanwhile, were happily collecting booty from the lower city, forgetting that a huge Muslim army was on its way.

The Crusaders Besieged

Kerbogha arrived at Antioch on 7 June and camped in the same positions the Crusaders had occupied for so long. The besiegers were now the besieged. The Crusaders built a wall to isolate the upper citadel from the lower fortifications and launched unsuccessful sorties on the forces outside. With starvation once again the most serious threat, the Crusaders could only await the hoped-for rescue by an army sent by Alexios. It was then that an unfortunate misunderstanding occurred with long-lasting consequences. The Byzantine emperor was indeed on his way to Antioch, but he met in transit refugees from the city who wrongly informed him that the Crusaders were on the brink of defeat to a huge Muslim army, and so the emperor returned home seeing no point in wasting resources on a lost cause. When news arrived of another Turkish army heading to intercept Alexios before he even got to Antioch, it seemed prudent to withdraw. Bohemund, in particular, was not best pleased to find out he had been abandoned by the Byzantines, and the Norman decided to renege on his vow to return all captured territory to the Emperor. He would keep Antioch for himself if he could just hold onto it, and the relations were thus irrevocably soured between the Crusaders and Byzantines.

Meanwhile, Kerbogha made a concerted attack on the south-west wall on 12 June 1098 CE. Within a whisker of taking the towers, the Muslims were finally repelled. Things were now getting desperate for the Crusaders, and an appeal to Kerbogha to allow safe passage as the Crusader army withdrew from the city in surrender was rejected. Then a curious incident turned the tide of warfare again in the Crusader's favour as they were reminded why they were in Syria in the first place.

A peasant named Peter Batholomew approached the Crusader leaders and claimed that he had had a vision where Saint Andrew had shown him where one of the holiest relics in Christendom lay - the lance which had pierced the side of Jesus Christ at the crucifixion. Digging into the floor of the Cathedral of Saint Peter, the lance was miraculously found, and the news spread through the Crusader army that they now had a sure sign of divine favour, for legend told that he who carried the lance would defeat all comers. A full assault on the Muslim camps was planned and the timing was fortuitous as Kerbogha was already struggling to keep his coalition army together and desertions were rife. On 28 June the attack was launched with great success, watched, according to legend, by a host of ghostly white knights led by Saint George himself from the hills above. The Muslims panicked as large contingents retreated, their commanders having no wish to support Kerbogha. The forces on the citadel, seeing the futility of fighting on alone, surrendered the next day. Finally, the siege was broken, and Antioch was back in Christian hands.

Aftermath

In December 1098 CE the Crusader army marched onwards to Jerusalem, capturing several Syrian port cities on their way. They arrived, finally, at their ultimate destination on 7 June 1099 CE. After a short siege, the city was captured on 15 July 1099 CE. Alexios, meanwhile, wanted Antioch back and he sent a force to attack the city or at the very least isolate it from the surrounding Crusader-held territories. Bohemund had left, though, and returning to Italy, he convinced Pope Paschall II (r. 1060-1118 CE) and the French king Philip I (r. 1060-1108 CE) that the real threat to the Christian world was the Byzantines. Their treacherous emperor and wayward church had to be eliminated, and so an invasion of Byzantium, the precise location being Albania, was launched in 1107 CE. It failed, largely because Alexios mobilised his best forces to meet them, and the Pope abandoned his support of the campaign. As a result, Bohemund was forced to accept subservience to the Byzantine emperor, who let him rule Antioch in Alexios' name. Thus, the pattern was set for a carving up of future captured territories.

The story of the siege of Antioch quickly captured the medieval imagination with its trials and tribulations, defeats, privations, miracles, and final victory, as the historian C. Tyerman summarises:

The siege…provided the twelfth century with its Trojan War, famed in verse, song and prose, commemorated in stone and glass, the central episode of trial and heroism in epic and romantic recounting of the First Crusade. (135)