Ptolemaic Egypt rapidly established itself as an economic powerhouse of the ancient world at the end of the 4th century BCE. The wealth of Egypt was owed in large part to the unrivalled fertility of the Nile, which served as the breadbasket of the Ptolemaic Kingdom. Egypt's economy underwent numerous radical changes during the Ptolemaic period, including the introduction of Egypt's first official coinage, the cultivation of new crops, and the growth of international trade. Corrupt bureaucratic practices, droughts, military expenditures, and political unrest plagued the economy of the Ptolemaic dynasty as the kingdom went into a period of decline in the 2nd century BCE. Nevertheless, Ptolemaic Egypt remained one of the largest economies in the Mediterranean until the Roman conquest of Egypt in 30 BCE.

Managing the Egyptian economy

Instead of uprooting Egyptian tradition, the Ptolemaic dynasty incorporated pre-existing administrative practices when they assumed control of Egypt in the late 4th century BCE. Ptolemy II Philadelphus (c. 285 BCE – 246 BCE) laid the foundation of Ptolemaic economic policies by introducing new revenue and property laws and new taxes. Ptolemy II also began the distribution of 'instruction texts' describing ideal governmental behaviour to officials as an attempt to create some kind of bureaucratic standard.

The chief economic minister in Ptolemaic Egypt was the dioiketes, who was appointed by the ruling monarch to set Egypt's economic policies. All of the offices dealing with finances, agriculture, and record-keeping were under his auspices. As a matter of practicality, ancient Egypt was divided into administrative provinces known as nomes. At the nome level, officials dealt with municipal and village authorities to handle economic issues like land management, taxation, and the circulation of currency.

On the surface, Ptolemaic Egypt appears to be a highly organised bureaucracy, which early modern historians characterised as the product of a highly centralised despotic state. The Ptolemaic crown may have directed economic policies but these could only be enforced by local authorities who sought to increase their own power and prestige. To complicate the issue, the Ptolemaic government lacked a clear chain of command, and areas of responsibility frequently overlapped. The independent initiative of farmers and merchants should also not be discounted. The economy of Ptolemaic Egypt was therefore never the product of state-direction, but the result of overlapping fiscal, agricultural, and social influences. Sitta Von Reden in The Ancient Economy and Ptolemaic Egypt concisely summed this up

The transformation of a system into one based on coinage and contract, however, was not achieved by force or centralisation as previous scholars have argued; rather, it was a system carefully devised as a balance of state and local power, royal patronage and private initiative, as well as indigenous agrarian patterns and Greek innovation. (175)

Corruption plagued all levels of government and gave way to predatory bureaucratic practices. This condition persisted in spite of royal decrees forbidding the financial exploitation of Ptolemaic subjects by officials. As a result of the broken fiscal system, Ptolemaic rulers frequently began their reigns by providing blanket forgiveness on all debts owed to the government to help undo past damage from state corruption.

From the 3rd century BCE onwards, social and economic inequality caused uprisings and civil unrest, which further strained the Egyptian economy. The largest uprising occurred between 205 BCE and 185 BCE when Upper Egypt temporarily seceded from the Ptolemaic Kingdom with Nubian support. Upper Egypt was reconquered during the reign of Ptolemy V (204 BCE – c. 180 BCE), but the effects of this insurrection rocked Egypt and prompted the Ptolemaic dynasty to reform many aspects of its rule.

Landowners & Labourers

An estimated 30-50% of farmland in Ptolemaic Egypt was owned directly by the crown, with temple property making up another large category of land. Temples managed land, archived information, and owned large estates which supported temple expenses through agricultural output and taxation. Contrary to popular belief, private landowning did exist in Ptolemaic Egypt and is especially well attested in Upper Egypt.

The Ptolemaic dynasty granted allotments of arable land to cavalry and infantrymen for their lifetime in order to create a loyal landowning class of soldiers (referred to as cleruchs) comparable to that of Greece and Macedon. Cleruchs were predominantly Greeks, Thracians, Cyrenians, and Hellenized Egyptians whose sons inherited their status and received 'gift-estates' of their own upon entering military service. Officials and favourites of the royal family were also given estates.

As elsewhere in the ancient Mediterranean, the majority of the Egyptian population were agricultural labourers. Most were tenant farmers who lived and worked on rented or leased plots of land. Tenant farmers were provided with farming equipment by their employers and loaned seed. Wage labour was also quite frequently used by both the crown and estate holders. Ptolemaic subjects were summoned by the crown for labour levies at certain times of year when extra manpower was needed to assist in the plantings and harvests.

Agriculture

In the Ptolemaic period, Egypt was a major producer of grain, wine, flax, cotton, papyrus, and a wide range of fruits, vegetables, and spices. The introduction of new crops, the cultivation of wine and olive oil during the Ptolemaic period played an important role in the transformation of Egyptian food and culture at this time. The earliest investors in this agricultural revolution were cleruchic soldiers or Ptolemaic officials like Apollonius, the dioiketes of Ptolemy II. Olives and grapes gradually became staple crops as the traditional diet became increasingly influenced by Mediterranean cuisine in Ptolemaic and Roman Egypt. Wine had been cultivated in Egypt for millennia but the consumption of wine in Egypt was nowhere near as ubiquitous or culturally significant as it was in Greece. The climate in most of Egypt did not lend itself to winemaking and Egyptian wine was notoriously poor. To help improve vintages, some vineyard owners imported older vines from Greece at high costs to cultivate in Egypt.

During the Ptolemaic period, Egyptian farmers began to cultivate durum wheat in place of the emmer wheat and barley. These new grains fetched higher prices on foreign markets and were more popular with Hellenistic and Near Eastern settlers in Egypt. The downside was that these new crops required even more water than the traditional Egyptian staples they replaced. In the late 3rd century BCE, large systems of canals were constructed to irrigate land that was otherwise too far from the Nile to be fed by the river. These canals were maintained through a combination of contracted wage labour and labour levies.

New irrigation techniques also played a role in opening up more land for agricultural use. At this time, a massive land reclamation program was launched to drain the marshy Fayum, which would become an important agricultural zone in Ptolemaic Egypt. The reliance on the Nile's annual flooding, rather than rain, was both a gift and a weakness of Egypt. The Nile's failure to fully flood in certain years led to periodic droughts and famines. To cope with these recurring famines, government stockpiles of grain and lentils might be sold on the market or distributed to the people.

Money in Ptolemaic Egypt

Prior to Alexander the Great's conquest of Egypt, the country had never used a system of minted coinage. Instead, exchanges were carried out in kind or barter at fixed rates. Wheat was most commonly traded in Egypt along with precious metals like gold, silver, and copper. Egyptian imitations of the Athenian currency were minted in the 4th and 5th centuries BCE, and the 30th Dynasty of Egypt introduced the Egyptian gold stater (c. 360 BCE) in order to pay Greek mercenaries. However, these were never used widely and were discontinued after the Achaemenid Persian conquest of Egypt in 343 BCE.

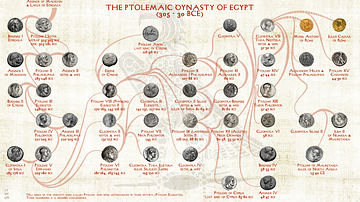

After Alexander the Great (336 BCE - 323 BCE) conquered Egypt, coins from Macedon and the rest of his empire began to circulate in the country. While Egypt was a satrapy of Alexander the Great's empire, drachmae began to be minted in Egypt and used by the elite. Despite these developments, Egypt did not truly have a minted currency of its own until the reign of Ptolemy I. The Ptolemaic Kingdom minted Egyptian coins which were roughly equivalent to the standard Greek denominations of the chalkous, obol, and drachma.

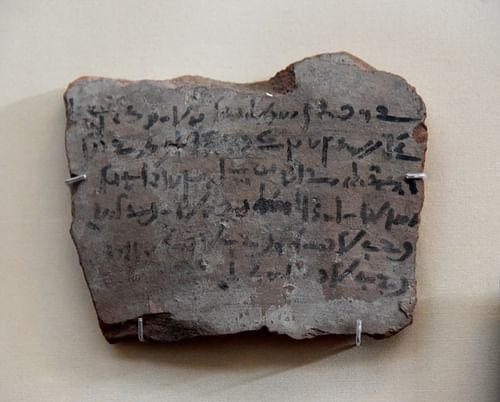

Coinage served a practical purpose as a means of creating a partially monetised economy, but it also served as political propaganda. This new system of money was used throughout Egypt, although trade in kind continued to be used in everyday transactions by both Hellenes and Egyptians. These transactions were recorded by receipts in Greek or Demotic Egyptian which were written on ostraka (potsherds).

Sources of gold and copper were relatively plentiful but silver, the standard of Hellenistic currencies, had always been scarce in Egypt and had to be imported. To deal with the limited silver supply, Ptolemy I (323 BCE - 285 BCE) reduced the silver and gold drachmae to 80% of their original weight by 305 BCE. The calibre of Ptolemaic currency as a whole varied wildly as later monarchs debased the currency by reducing the percentage of precious metals in order to finance wars or cope with economic hardship.

A closed currency system was created by the outlawing the use of foreign currencies in Egypt in the early 3rd century BCE. Any foreign merchants looking to purchase goods in Egypt were required to exchange their currencies for Egyptian money at a 1:1 rate. The royal administration pocketed the profit made from this exchange of foreign coins for lower value Egyptian currency.

A major reform took place around 260 BCE. Firstly, new silver denominations were added to the existing ones. Secondly, heavier bronze coins were minted that could partially replace silver in large transactions. The largest of these new bronze coins weighed between 69-72 grams and was roughly equivalent to one silver drachma. By the 230s BCE, bronze had essentially replaced silver in daily transactions, something unheard of in the Greek world.

Ptolemy IV (221 BCE – 204 BCE) dramatically reduced the weight of bronze coins. As a result, the spending power of bronze was halved, and a 'silver standard' took over, which became increasingly burdensome to rural labourers who were paid in bronze. In reaction to these developments, Ptolemy V (205 BCE – 180 BCE) completely overhauled the monetary system in 197 BCE and introduced new bronze denominations. The most dramatic debasement of silver occurred during the reign of Ptolemy XII (80 BCE - 58 BCE, second reign from 55 BCE - 51 BCE) who decreased the silver purity to 33% in 53 BCE as an attempt to pay off his enormous debts to Roman creditors. Cleopatra VII (55 BCE - 30 BCE) reformed the monetary system in 51 BCE. Her reforms included the introduction of new bronze denominations and the reduced purity of Ptolemaic silver drachmae by more than 50% to match the Roman denarius.

Taxation

Taxation was the most important source of revenue available to the Ptolemaic crown. Most taxes could be paid in kind, only a few had to be paid in coin. In order to assess taxes, fields, orchards, and vineyards were periodically surveyed. Agricultural produce and crafted goods were taxed at every stage of production, from harvest to final sale. Not only were goods and land taxed but also individuals, their children, and their slaves. To this end, a number of censuses were carried out by scribes at regular intervals.

Not all Ptolemaic subjects were taxed at the same rates. Eligibility for reduced taxation was assessed based on a number of factors tied to occupation and social class. Citizens of cities like Alexandria and Ptolemais, as well as residents of the nome capitals, were exempt from certain annual taxes and paid others at reduced rates. Landowners who had planted vines with their own funds paid reduced taxes on their vineyards.

Individuals were obligated to pay different taxes depending on their ethnic status in the census. Hellenes (Greeks) paid fewer taxes than groups like Egyptians or Cyrenians (Libyans). Although these statuses were defined by ethnic terms, they did not have to reflect the actual ethnicity of the individual. These ethnic labels were in reality strongly tied to culture and occupation. The most notable examples of this are the designation of all priests as Hellenes for tax purposes and the designation of ethnic labels according to a soldier's military role. Teachers and actors were given similar exemptions because they were seen as promoters of Greek culture.

Manufacturing Goods in Ptolemaic Egypt

Along with staples like grain and papyrus, Ptolemaic Egypt exported luxury items and commodities to the Near East, Greece, Roman Italy, and Meroe. Large workshops in Egypt turned raw materials into finished products such as dyed cloths, jewellery, and artworks, which were sold domestically or exported throughout the ancient world. Both free labourers and slaves toiled in these workshops to weave and craft the finished products.

For much of Egyptian history, linen was the preferred textile, but this began to change in the Ptolemaic period. Wool was the preferred garment of the Greek settlers who immigrated to Egypt during the reign of the Ptolemies, and new industries emerged to supply their needs. To this end, sheep from regions such as Milos in Greece were imported. Wool was often dyed brightly with both Egyptian and imported colours and used to produce rugs, clothing, and other tapestries.

The traffic of cosmetics, medicines, and perfumes was an important industry in Ptolemaic Egypt. Although some of the ingredients for these products had to be imported, many were also produced domestically as Egypt had rich agricultural and mineral resources. Minerals found in Egypt, like natron, malachite, and limestone, were used in the production of medicinal and cosmetic products, which were prized and imitated throughout the ancient world.

Glass and pottery were also important products, used for a variety of purposes ranging from everyday eating and drinking vessels to more refined jewellery and art. Egyptian faience was particularly sought after throughout the Mediterranean for its glossy texture and bright colour.

Trade in Ptolemaic Egypt

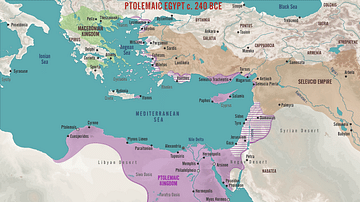

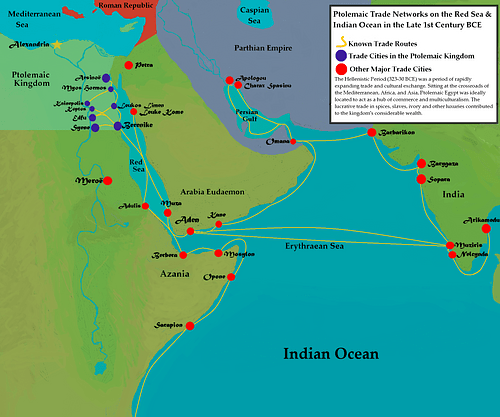

Egypt had been an important centre of trade for millennia, but the volume and reach of Egyptian trade multiplied during the Ptolemaic period. Alexandria was purposely placed at the crossroads of Africa, Asia, and Europe to encourage commerce, and the city developed into one of the most important commercial hubs of the ancient Mediterranean. Mediterranean goods flowed into Alexandria to feed the cultural appetites of a rapidly growing Hellenistic metropolis. Greek wine and pottery from regions like Crete and Cyprus were particularly heavy imports to the capital. Wine and other goods were also imported from the Italian peninsula, with Roman-Egyptian trade becoming increasingly important in the 2nd and 1st centuries BCE.

Port cities on the Egyptian the Red Sea coast were conduits of both maritime and overland trade to Egypt from Asia and Africa. Various Arabian polities acted as intermediaries for Egyptian-Near Eastern trade, and Arabia itself was an important source of items like frankincense and myrrh. Silver was imported from the Near East to help supplement Egypt's lack of adequate silver resources. The Red Sea trade also indirectly connected Egypt to Southeast Asia and the Indian subcontinent. Chinese silk, tortoiseshell, and exotic spices were imported as expensive luxury items.

Besides spices, India was a primary source of war elephants for the Ptolemaic army. The fact that this trade had to be conducted overland meant that, by the 2nd century BCE, the expansion of the Seleucid Empire had cut off the Ptolemaic Kingdom's access to war elephants. The need for an alternate source was a key factor in the increase of Ptolemaic trade with East Africa. The first recorded use of Ethiopian or "Troglodytic" elephants for warfare dates from the reign of Ptolemy III (246-222 BCE). However, these African elephants proved to be no match for their Indian counterparts and their use was discontinued after the Battle of Raphia (217 BCE).

Trade between Egypt and other parts of Northeast and East Africa was highly lucrative during the Ptolemaic period. Trading posts and small cities on the Nubian border in the Dodekaschoinos were an important source of gold and exotic game animals. Ptolemaic maritime trade on the East African coast extended as far south as cities like Sarapion and Nikon in modern-day Somalia. Ivory, gold, and frankincense were some of the more important goods in this coastal trade due to the high prices they fetched on the Egyptian market. A wide array of ivory furniture, artworks, and personal ornaments were created in Ptolemaic Egypt at this time as the material was both exotic and easily carved.

Echoes of Ptolemaic Policy in Roman Egypt

The Roman state did not completely uproot the old systems of the Ptolemaic administration. Most of the royal bureaucratic offices were replaced by Roman officials. Land which had formerly belonged to the Ptolemaic crown was reorganised into ager publicus or public land, and the rents and taxes they generated were paid directly to the Roman treasury. Even the closed monetary system was retained until 296 CE.

Roman rule did bring certain immediate changes to the Egyptian economy, however. Certain regions of Egypt, particularly Upper Egypt, were subject to harsh taxation which led to several revolts within the first few years of Roman rule. The Hellenistic system of landed soldiers was dismantled and replaced by the garrisoning of Roman legions in Egypt. Becoming a part of the Roman Empire also meant integrating into what is often considered to be the earliest example of a global economy, with all of its upsides and downsides. Egypt's already considerable trading importance increased dramatically during the Roman period, although in many respects this disproportionately benefited Rome.