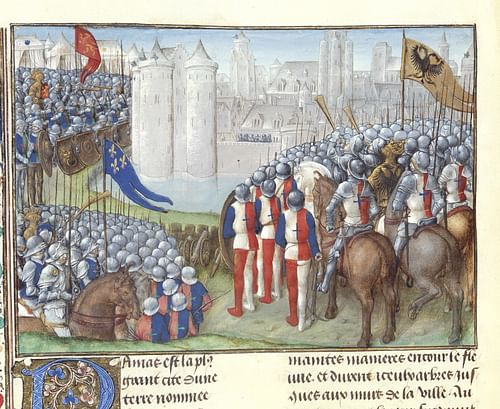

The siege of Damascus in 1148 CE was the final act of the Second Crusade (1147-1149 CE). Lasting a mere four days from 24 to 28 July, the siege by a combined western European army was not successful, and the Crusade petered out with its leaders returning home more bitter and angry with each other than the Muslim enemy. Additional crusades would follow, but the myth of invincibility of the western knights was shattered forever at the debacle of Damascus.

Background: The Second Crusade

The Second Crusade was a military campaign organised by the Pope and European nobles to recapture the city of Edessa in Mesopotamia, which had fallen in 1144 CE to the Muslim Seljuk Turks. Edessa was an important commercial and cultural centre and had been in Christian hands since the First Crusade (1095-1102 CE). However, when Pope Eugenius III (r. 1145-1153 CE) formally called for a crusade on 1 December 1145 CE, the goals of the campaign were put somewhat vaguely as a broad appeal for the achievements of the First Crusade and Christians and holy relics in the Levant to be protected.

The Second Crusade included successful campaigns in the Iberian peninsula and the Baltic against Muslim Moors and pagan Europeans respectively, but it was the Levant that remained the focus of Christianity's holy war. The Crusader army in the Middle East, numbering some 60,000 men, was led by the German king Conrad III (r. 1138-1152 CE) and Louis VII, the king of France (r. 1137-1180 CE). Just as in the First Crusade, the bulk of the army travelled via Constantinople where they were met with misgivings by the Byzantines and their emperor Manuel I Komnenos (r. 1143 - 1180 CE). Manuel's primary concern was that the Crusaders were really only after the choice parts of the Byzantine Empire. Accordingly, Manuel insisted the leaders of the Crusade, on arrival in September and October 1147 CE, swear personal allegiance to him. At the same time, the western powers considered the Byzantines rather too preoccupied with their own affairs and unhelpful in the noble opportunities they thought a crusade presented. The old divisions between the eastern and western churches had not gone away either. It was significant that Manuel, despite the diplomacy, strengthened the fortifications of Constantinople and provided a military escort to see the Crusaders on their way as quickly as possible.

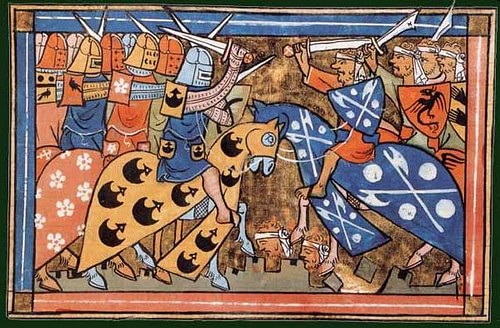

The German contingent of the crusader army, already having suffered significant losses during a terrible flash flood at their camp near Constantinople, ignored Manuel's advice to stick to the safety of the coast once in Asia Minor and so met another, even worse disaster. At Dorylaion, a force of Muslim Seljuk Turks caused havoc with the slow-moving westerners on 25 October 1147 CE, and, forced to retreat to Nicaea, Conrad himself was wounded but did eventually make it back to Constantinople.

Meanwhile, the army led by Louis VII, although shocked to hear of the Germans' failure, pressed on and managed to defeat a Seljuk army in December 1147 CE. The success was short-lived, though, for on 7 January 1148 CE the French were beaten badly in battle as they crossed the Cadmus Mountains. It was a disastrous opening to a campaign which had not even reached its target of northern Syria and a sorry tale of bad planning, poor logistics, and unheeded local advice.

Louis VII and his ravaged army finally arrived at Antioch in March 1148 CE. From there, he ignored Raymond of Antioch's proposal to fight in northern Syria and marched on to the south. In any case, a council of western leaders was convened at Acre, and the target of the Crusade was now selected, not at the already destroyed Edessa, but Muslim-held Damascus, the closest threat to Jerusalem and a prestigious prize given the city's history and wealth.

The Great City of Damascus

Although Damascus, located in southwest Syria, had once been an ally of the Crusader-led Kingdom of Jerusalem, the shifting loyalties between the various Muslim states in the Levant meant this fact held no guarantee for the future and, faced with the necessity to take at least one major city or go home as complete failures, Damascus was as good a choice as any for the Crusaders. Indeed, two attempts had already been made to take the city by the Franks, as the western settlers in the Middle East were widely known, in 1126 and 1129 CE. The situation was now made more urgent as there was a very real prospect that the Muslims of Damascus would join up with those of Aleppo under command of Edessa's most recent conqueror, the ambitious Nur ad-Din (sometimes also given as Nur al-Din, r. 1146-1174 CE). Sure enough, the Muslim military commander or atabeg of Damascus, the city's ruler in practical terms, was Mu'in al-Din Abu Mansur Anur (aka Mu'in al-Din 'Unar, r. 1138-1149 CE), and in 1147 CE he had arranged for his daughter to marry Nur ad-Din. The Muslim world was beginning to unite against the repeated attacks by western armies.

Damascus gained its wealth from its advantageous position on the caravan routes and Silk Road, as well as its control of a vast agriculturally rich hinterland. The city, too, had a religious significance for both Christians and Muslims. The capital of the Umayyad Empire from 661 to 750 CE, the city had been a great centre of learning and the arts and boasted such fine architecture as the 8th-century CE Great Mosque which contained one of Islam's holiest relics, the Koran of the Caliph Uthman, one of Muhammad's early successors. Further, nearby Mount Kaisoun was regarded as the birthplace of Abraham and, in Muslim tradition, Damascus was to be the place of the Messiah's arrival before the Day of Judgement. It was a city worth fighting for both for ideological and financial reasons.

The Muslim army tasked with defending Damascus was composed of a professional core, the askars, and a mixed bag of supplementary forces which included a militia, the ahdath, drawn from the poorer elements of the city and its large surrounding territory; Turkoman and Kurdish volunteers; troops provided by states under the rule of Damascus - notably a sizeable contingent of archers from Lebanon; and, finally, Arab Bedouin allies. It was these forces that would have to hold the city against the feared western knights.

The Siege

When news of the Crusader army's approach reached Mu'in al-Din, the commander set about spoiling all wells and water sources on the invaders' probable approach route. The Crusader army, split into three contingents with one each led by Louis VII, Conrad III, and Baldwin III of Jerusalem (r. 1143-1163 CE), arrived at Damascus on 24 July 1148 CE and immediately attacked. Indeed, although the historical accounts are notoriously confused and conflicting, it seems that the Crusaders expected the city to fall within days and they made no contingency plans in the case of a protracted defence.

After the Crusaders crossed the city's outlying irrigation channels, Mu'in al-Din sent out his army to prevent the Crusader force from crossing the Barada River. Baldwin's and Louis' forces were kept back, but Conrad's force broke through the lines, and the Muslims were forced to retreat back through the difficult terrain of orchards and low-walled copses - which stretched some 8 km (5 miles) out from the city walls - finally reaching the safety of the city's defensive walls.

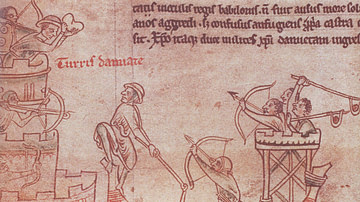

The crusader army, perhaps then numbering some 50,000 men, moved forwards, taking control of the western approach to the city. At Rabwa, fortifications were built to cut off Damascus from the Biqa'a Valley. The suburbs of Faradis were the first to be attacked, and by the 25th a fortification was constructed outside the Bab al-Jabiya gate using wood from the city's orchards. The siege was underway, but Mu'in al-Din had already sent for help from Nur ad-Din at Aleppo and Sayf al-Din Ghazi at Mosul (r. 1146-1149 CE).

By the end of the day of 25 July, the Crusader army set up camp on the Green Maydan (Maydan al-Akhdar), the grassy area used by the Damascan cavalry as a training ground. The city sent out a force to repel the attackers and a day of heavy fighting ensued, especially to the north of Damascus. The defenders sustained heavy losses, but it is likely they did clear this area and so permit reinforcements to arrive from Lebanon and Sayf al-Din on 26 and 27 July. It is also probable that the Crusaders intended to now concentrate on either the eastern or the southern edge of the city and the weakest of the gates, the Bab al-Saghir or 'Small Gate' built only of mud bricks - even if these areas were much less advantageous for food and water supplies. However, Mu'in al-Din organised major attacks on the Crusader camps with a force which included anyone who could carry arms, as described here by the Muslim historian Abu Shama (1203-1268 CE):

A large group of inhabitants and villagers…put to flight all the sentries, killed them, without fear of the danger, taking the heads of all the enemy they killed and wanting to touch these trophies. The number of heads they gathered was considerable. (Nicolle, 71)

Meanwhile, the city's inhabitants strengthened their own, rather poor fortifications using wooden palisades. Damascus was proving to be a much more difficult target than the westerners had anticipated, and to improve moral, a relic of the True Cross was paraded about the Crusader camps.

On 28 July the Crusaders moved their main base camp from the Green Maydan but, before settling on a new site and after only four days of siege, the leaders decided to withdraw from Damascus the next day. Even then, the westerners had to face fierce harrying attacks to their rear as they tried to regroup to the south. The siege of Damascus was a lacklustre final episode of the campaign, and nothing short of a debacle considering the original glorious intentions of those who had organised the Second Crusade.

Causes of the Failure

The causes of the Crusader's failure were multiple:

- the difficulties presented by the defences - principally the terrain and sheer size of the city

- the hit-and-run guerrilla tactics of the defenders and their tenacity

- the continued harassment from the local militia in the outlying territories of Damascus

- and the serious lack of food and water for the attackers.

All of these factors combined meant the siege had to be abandoned. It is also interesting to note that neither Christian or Muslim sources mention the presence of siege engines. Once again, bad planning and poor logistics were to prove the Crusaders' undoing. The fighting around the city had been ferocious with heavy casualties on both sides, but no real advance had been made over the four days. The absence of a determined pre-set plan backed by appropriate logistics and siege weaponry had proved fatal. The failures of the Second Crusade were now putting the already legendary successes of the First Crusade into some perspective.

The collapse of the siege after such a short time led some, notably Conrad III, to suspect the defenders had bribed the Christian residents into inaction. Others suspected Byzantine interference. There was probably disagreement and suspicion amongst the Crusader factions, especially between those already established in the Levant and the newer arrivals, and between leaders over what exactly to do with Damascus if and when it was captured. Overlooked too, perhaps, is the zeal of the defenders to keep their prized possession and the arrival of a large Muslim relief army 150 kilometres away, sent by Nur ad-Din. With limited numbers and supplies and facing a short time limit to capture the city before relief arrived and threatened their own poor defences, the Crusader leaders may have preferred the option of retreat to fight another day. There was to be no other fight, though, as the army retreated to the Kingdom of Jerusalem. Conrad III returned to Europe in September 1148 CE, and Louis, after a sightseeing tour of the Holy Land, did the same six months later. The Second Crusade, despite so much early promise, had disappointingly fizzled out like a water-damaged firework.

Aftermath

Nur ad-Din, as the Crusaders no doubt had feared, continued to consolidate his empire, and he took Antioch on 29 June 1149 CE after the battle of Inab, beheading its ruler Raymond of Antioch. Raymond, the Count of Edessa, was captured and imprisoned, and the Latin state of Edessa was eliminated by 1150 CE. Next, Nur ad-Din took over Damascus in April 1154 CE following the death by natural causes of Mu'in al-Din, thus uniting Muslim Syria. The Muslims would pose a permanent threat to both the Byzantine Empire and the Latin East. When Nur ad-Din's general Shirkuh conquered Egypt in 1168 CE, the way was paved for an even greater threat to Christendom, the great Muslim leader Saladin (r. 1169-1193 CE), Sultan of Egypt, whose victory at the Battle of Hattin in 1187 CE would spark off the Third Crusade (1189-1192 CE).