The Siege of Acre, located on the northern coast of Israel, was the first major battle of the Third Crusade (1189-1192 CE). The protracted siege by a mixed force of European armies against the Muslim garrison and nearby army of Saladin, the Sultan Egypt and Syria (r. 1174-1193 CE), lasted from 1189 to 1191 CE. Thanks to their impressive siege weapons and tactics, and the leadership of such men as Richard I of England (r. 1189-1199 CE), the Crusaders captured the city on 12 July 1191 CE. It was a morale-boosting victory, but Saladin's army remained largely intact, and the two sides clashed again two months later at Arsuf. Once again the Crusaders won the battle but, with each new clash, the western armies were depleted so that the real goal of retaking Jerusalem slipped ever further from their grasp.

The Third Crusade

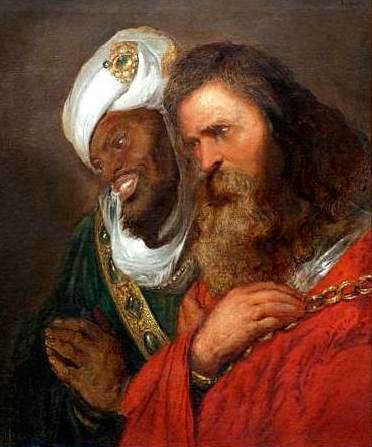

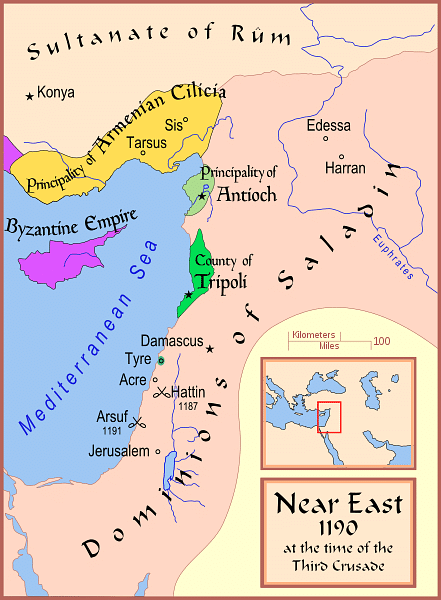

The Third Crusade (1189-1192 CE) was launched to retake Jerusalem after the Holy City was conquered in 1187 CE by the Muslim leader Saladin. Saladin had already taken control of Damascus in 1174 CE and Aleppo in 1183 CE and defeated the Latin allied states at the Battle of Hattin in 1187 CE. Thus, the Muslim leader was able to take control of such cities as Acre, Jaffa, and Jerusalem. The Latin East, as those states created by the early Crusaders were collectively known, had all but collapsed and only Tyre remained in Christian hands, under the command of Conrad of Montferrat.

Pope Gregory VIII (r. 1187 CE) responded to these disasters by calling for the Third Crusade in order to win back Jerusalem and such lost holy relics as the True Cross. Europe's three most important monarchs took up the Pope's challenge: the Holy Roman Emperor, Frederick I Barbarossa, king of Germany (r. 1152-1190 CE), Philip II of France (r. 1180-1223 CE) and Richard I 'the Lionhearted' of England.

Three armies headed for the Holy Land; Frederick's by land where it met with total disaster after the emperor fell from his horse and drowned on 10 June 1190 CE in the River Saleph in southern Cilicia. Of those soldiers who did not trudge home in despair, many were killed by an outbreak of dysentery. Meanwhile, both Philip and Richard's armies travelled to the Middle East by sea, Richard capturing both Sicily and Cyprus en route. Thus, the Crusaders arrived at Acre in early June 1191 CE and gave a much-needed boost to the ongoing siege of the city.

Guy of Lusignan Besieges Acre

Prior to 1187 CE Acre had been an important coastal city of the Kingdom of Jerusalem, one of the states created by the Crusaders who had settled in the Middle East. The port city, built on a peninsula with the west and south sides protected by the sea and the other two sides by massive walls, had fallen, like Jerusalem, to Saladin. The Muslim leader was then quick to refortify the city and make it one of his most important garrisons and arms depots.

The French nobleman Guy of Lusignan, king of what remained of the Kingdom of Jerusalem (r. 1186-1192 CE), decided to make an attack on Acre in 1189 CE. Considering the precarious position of the Latins in the region, it was a daring move, perhaps motivated by the necessity to make some sort of fightback against the Muslim incursions and mobilise while Saladin was still busy securing several other castles in the region, notably at Beaufort where a siege was ongoing. In addition, with his rival Conrad of Montferrat in control of Tyre, Guy was effectively a king without a kingdom. Acre could provide him with a base of his own from which he could stake his claim to any newly-created Latin states when the promised Crusader armies arrived in the region.

Guy mustered some 7,000 infantry, 400 knights, and a small Pisan fleet, and left Tyre to block the land approach to Acre in August 1189 CE. Unfortunately, the Pisan ships could not create a total blockade of Acre's harbour, and even in the city itself, the entrenched garrison was punching above its weight thanks to the presence of some of Saladin's elite troops. Guy's initial direct attack on the city was rebuffed, and he set up a fortified camp on the small hill, Mount Toron, east of the city. A siege was the only way forward, but at least Guy could receive constant reinforcements from Tyre thanks to the freedom of movement enjoyed by his own fleet. In September 1189 CE, the besiegers were boosted by the arrival of some 12,000 troops from Denmark, Germany, England, France, Frisia, and Flanders. It was not the main Crusader armies but it was, anyway, a significant help.

Guy eventually encircled the land sides of Acre with a double line of fortified positions, but he did not achieve any great progress in threatening the city. The Frenchman was soon seriously endangered himself by a relief army sent by Saladin using troops from vassal states in Syria and Jazira. The cautious Saladin had allowed the Latins to reach Acre, putting off a direct attack on the enemy army as it mobilised from Tyre. However, now that he had assembled a large enough field army for the task, the besiegers had become the besieged. Saladin launched a direct but failed attack on Guy's fortified camp on 15 September 1189 CE. On 4 October 1189 CE the Christian army returned the favour and launched a full-on assault of Saladin's camp. With heavy casualties on both sides, neither force gained the upper hand.

The Latin army, although having to repel more direct attacks on their lines by Saladin's land army, settled down for a stalemate siege and a sort of trench warfare ensued. One eye-witness account reports the horror of the conditions:

While our people sweated away digging trenches, the Turks harassed them in relays incessantly from dawn to dusk…the air was black with a pouring rain of darts and arrows beyond number or estimate…no small number of them [new arrivals by sea] died soon afterwards from the foul air, polluted with the stink of corpses, worn out by anxious nights spent on guard, and shattered by other hardships and needs. There was no rest, not even time to breathe. (Quoted in Tyerman, 413)

The atrocious conditions of winter did bring a ceasefire of sorts, there were even episodes of the two sides playing games, singing together, and exchanging dinner invitations during the frequent lulls, but disease, as so often in medieval warfare, proved the most dangerous enemy of all. Even Guy's wife, Queen Sibylla, and their two daughters died in the autumn of 1190 CE of disease.

In the spring of 1190 CE, more ships arrived bringing Crusader reinforcements. Meanwhile, Saladin was also receiving reinforcements, and the fall of Beaufort on 2 April 1190 CE meant he could now concentrate on Acre. The stakes of the game were rising. On the 5 May 1190 CE, the Christian army attacked the city with three huge siege engines, but all were destroyed by the defender's Greek Fire, a highly flammable liquid sprayed under pressure at anything that might burn. A small flotilla of Egyptian ships was even able to avoid the Christian flotilla and resupply the city. The attackers were, though, boosted by the arrival of a contingent of French troops under the command of Henry of Champagne on 28 July 1190 CE. More attacks and counterattacks followed between the two sides but without any decisive results.

A group of Frederick's once-mighty army now under the command of Duke Leopold of Austria arrived on 7 October 1190 CE, but it was not enough. Another winter season came and went as the stalemate dragged on. Aware of the coming European kings and their large armies, Saladin made an extra push to break the ring of the Crusader army around Acre on 13 February 1191 CE. The lines were breached and the city's defences bolstered by new troops with a new commander, but it was a temporary gain, and the Crusaders closed the trap once more. It was back to square one, it seemed.

The westerners must then have been mighty glad to finally see the arrival of Philip and Richard in June of 1191 CE, the latter with a fleet of over 200 ships carrying food, equipment, and perhaps 17,000 men. As well as these two kings' troops, there were other, smaller forces led by various nobles, and the ever-larger Crusader naval fleet was now able to completely blockade the harbour, not only cutting off the defenders' supply lines but also blocking in the bulk of Saladin's naval fleet, some 70 Egyptian ships. Saladin reinforced his land army to meet the increased threat from the new arrivals. Acre had turned into the pivotal engagement of the Third Crusade.

The Fall of Acre

Saladin was paying for the lack of unity in the Muslim states. The Sultan needed allied ships to break the naval blockade at Acre but the Muwahhids Caliph in Morocco refused to send aid. Even worse, the Crusader ships were easily finding ports for resupply along the North African coast, and more and more of them were arriving at Acre. When a Genoese fleet arrived on the scene in mid-June, the balance swung definitively in the Crusader's favour. If Saladin were to keep hold of Acre, it would have to be by using only the land army. Even here, though, he had lost the support of his own nephew Taqi al-Din, who withdrew to pursue his own conquests in south-east Turkey.

The Crusader armies, now totalling some 25,000 men, had brought massive siege catapults to add to those of Guy's army - the names of these weapons, like 'Bad Neighbour' and 'God's Stonethrower', indicate their potency - and Richard also had a siege tower built. The walls of Acre were pounded relentlessly as Richard, in particular, roused the besiegers to greater efforts, even firing his crossbow from his stretcher when he briefly succumbed to an illness, possible scurvy. Another crucial strategy was Richard offering cash incentives to the sappers given the task of undermining the city's defensive walls from below - two gold coins (later raised to three and then four) for every stone removed from the defences. The Maledicta Tower, the 'Accursed” Tower, which stood at the angle of Acre's two lines of walls, was collapsed in this way, although the defenders proved resolute even amongst its ruins.

Meanwhile, Saladin kept up the pressure from the land side, but eventually, after one final coordinated attack between the garrison and Saladin's land army failed, the city capitulated on 12 July 1191 CE. The garrison of Acre had surrendered, which included an agreement to give up the 70 Muslim ships in the harbour without Saladin's consent, and by the time the Muslim leader had learnt of their intentions via a swimmer messenger, the deed was done. Saladin then withdrew his army to al-Kharruba, several kilometres to the south of Acre.

There was some confusion in the Crusader ranks too in the immediate aftermath of the battle. Duke Leopold, seeing himself as the representative of the Holy Roman Empire, allowed his men to hoist his flag above the captured battlements. Richard, being a king and not a mere Duke (as well as being primarily responsible for the success), ordered the flag's removal (or his men acted on their own initiative). The banner was unceremoniously thrown into the moat of Acre, leaving only the English king's own standard flying. Leopold was upset by this slight, and thereafter he remained on cool terms with the 'Lionhearted', even organising the king's famous capture for ransom on behalf of Henry VI, the new Holy Roman Emperor, when the English king returned from the Crusade.

The Massacre of Prisoners

An even more controversial episode than the question of whose flags to put where was Richard's treatment of the city's inhabitants. 2,500 prisoners (or perhaps 3,000, depending on sources), including women and children, were summarily executed on Richard's orders on 20 August 1191 CE. Other prisoners had already been exchanged between the two sides, including some nobles who could be profitably ransomed, but it seems that there was a delay of some kind, the relic of the True Cross was not returned as promised, and the English king was suspicious of the enemy's dithering as any delay meant Saladin could better prepare for the next confrontation as the Crusaders moved south. The bound prisoners were mercilessly cut down using swords, lances, and even stones. Although some of Saladin's remaining troops tried to intervene, they could not prevent the massacre. Saladin had been remarkably generous with his prisoners in the previous years, although he had had no qualms at all about executing any knights belonging to the military orders. The contrast in the treatment of civilian prisoners was a stark one, even if some have argued that Richard could not have allowed the men their freedom when he was just about to march southwards and so leave his army open to an attack from the rear if the prisoners had organised themselves into a fighting force.

Aftermath

Guy of Lusignan was made the new king of Cyprus, which had been sold by Richard to the Knights Templar to raise more cash for the Crusade. Unfortunately, Philip was obliged to return home in August 1191 CE due to political problems in Flanders which threatened his throne. Still, Acre was an excellent capture, and although many men and resources had been lost in its gain, the Crusader army was ready to march further south and take on the much bigger challenge of capturing Jerusalem. It seemed that the tide had turned and Acre was a morale-boosting victory, just as it was a damaging loss to Saladin, not perhaps in men or material but certainly to his carefully cultivated aura of invincibility.

As it turned out, the western army would be harassed continuously as it marched onwards. The two sides clashed again in September at the battle of Arsuf. Although a victory was gained against Saladin, the Crusaders were so depleted and the weather was so poor that a siege of the Holy City was abandoned. The task would have to be completed by calling the Fourth Crusade in 1202 CE which, in the event, again got side-tracked by prizes elsewhere and, instead of taking Jerusalem, attacked Constantinople in 1204 CE.