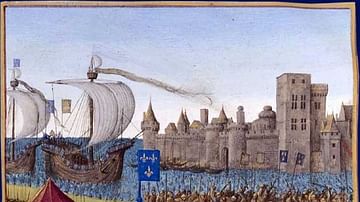

The Siege of Acre in 1291 CE was the final fatal blow to Christian Crusader ambitions in the Holy Land. Acre had always been the most important Christian-held port in the Levant, but when it finally fell on 18 May 1291 CE to the armies of the Mamluk Sultan Khalil, the Christians were forced to flee for good and seek refuge on Cyprus. The Fall of Acre, as the shocking defeat became widely known in the West, was the last chapter of the Crusade story in the Middle East.

The Mamluk Sultanate

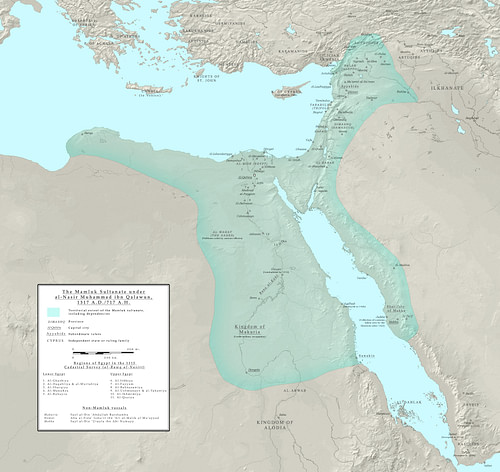

The military disasters of the Seventh Crusade (1248-1254 CE) and the abandonment of the 1270 CE Eighth Crusade following the death of its leader Louis IX, king of France (r. 1226-1270 CE), had effectively sealed the fate of the Crusader-created states, the Latin East. The Christians of the Levant stood alone to face two enemies at once: the Muslims of the Mamluk Sultanate based in Egypt and the invading armies of the Mongol Empire. Now merely a handful of coastal cities and isolated castles with no hinterland to speak of, the Latin East was impoverished and near total extinction.

The great Mamluk leader was Sultan Baibars (aka Baybars, r. 1270-1277 CE) who managed to expand his empire and push the Mongols back to the Euphrates River. The Christian cities suffered too, with Baibars capturing Caesarea and Arsuf. Antioch fell in 1268 CE and so too the Knights Hospitaller castle of Krak des Chevaliers in 1271 CE. The Muslim sect the Assassins were also targeted, and their castles in Syria were captured during the 1260s CE. Baibars was now master of the Levant and declared himself God's instrument and the protector of Mecca, Medina, and Jerusalem.

To face the threat to their existence, unlike the Christians of Antioch who had actually joined forces with the Mongols to take Aleppo, the Christians of Acre decided to remain neutral and side with neither the Muslim or the Mongols. Unfortunately, Acre was too strategically important a city and too prestigious a prize not to attract the attention of the Mamluks.

The Shrinking Latin East

The Latin East was not wholly abandoned after the Eighth Crusade, the future King Edward I of England (r. 1272-1307 CE) did arrive in Acre in 1271 CE with a small army of knights, but he could achieve very little before returning home to England to be crowned king the following year. Pope Gregory X (r. 1271-1276 CE) was keen to call another crusade in 1276 CE, but the expansion of Christendom in Spain and the Baltic proved more appealing endeavours for many European nobles and clergy alike. Gregory X pressed ahead anyway and set a tentative date of departure for a crusade in April 1277 CE, but when he died in January 1276 CE, the project was abandoned.

In 1281 CE the Christian-held fortress of Margat was captured by the Mamluks, Lattakiah was taken in 1287 CE, and then Tripoli in 1289 CE which was, like other captures, then demolished to deter any attempts at recapture and, most of all, to put off any future crusade being planned. Next in line for conquest was mighty Acre, long the base of Crusader armies, a place of final retreat in times of trouble, and capital of the Latin East. The pretext for the Mamluk siege was an attack by a small group of Italian Crusaders on Muslim merchants in the market of the city. When the Latins refused to hand over the perpetrators, the Mamluk Sultan decided the city would, one way or another, sooner or later, fall.

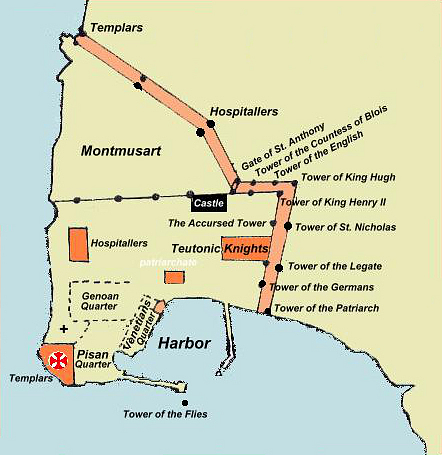

Acre

Acre had long been the most important port in the Levant for the Latin states ever since the creation of the Kingdom of Jerusalem after the First Crusade (1095-1102 CE). The port city was well-fortified, built on a peninsula with the west and south sides protected by the sea and the other two sides by massive double walls dotted with 12 towers. The city's formidable defences did not stop some leaders attacking and besieging it, most notably Saladin, the Sultan of Egypt and Syria (r. 1174-1193 CE), in 1187 CE, and then, to take it back again, the armies of the Third Crusade (1189-1192 CE) led by Richard I of England (r. 1189-1199 CE) in 1189 to 1191 CE. Acre then remained a Christian haven in a sea of ever-changing regional politics. The city had also been the headquarters of the medieval military order the Knights Hospitaller since 1191 CE. It had a strong force from the other two major military orders, the Teutonic Knights and Knights Templar, and in 1291 CE they would be sorely needed.

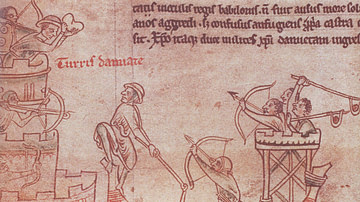

The Sultan of the Mamluks was then al-Ashraf Khalil (r. 1290 - 1293 CE), and he was determined to continue his father's work, Sultan Kalavun, and kick the Christians out of the Levant once and for all. He marched on Acre with a large force and suitable equipment to batter down its walls - perhaps with around 100 catapults. One of these massive catapults was taken from Krak des Chevaliers; called 'Victorious', it was so big it had to be dismantled, but even then it took a month and 100 carts to drag it to Acre, killing countless oxen from sheer exhaustion en route. Another giant catapult was named 'Furious', but perhaps the most useful artillery were the Mamluk's smaller and much more accurate catapults known as 'Black Oxen'. With an army assembled from across the Sultanate, the siege of the city began on 6 April 1291 CE.

The Siege

The population of Acre at this time was likely 30-40, 0000, although many civilians had already fled the city to take their chances elsewhere. Without a sizeable land army to engage the enemy in the field, the Christians who remained could do little but watch as Khalil methodically arranged his forces and catapults to cut off land access to the city. The defenders did have catapults of their own, they even had one or two mounted on their ships, and these fired boulders to try and damage those of Khalil now pounding Acre's walls with alarming regularity - both with stones and pottery vessels containing an explosive substance. It seemed only a matter of time before a breach was made, but the city was not defenceless. There were some 1,000 knights and perhaps 14,000 infantry ready to face the enemy if, or more likely when, they entered Acre. At least the Christians were still able to control the sea access and so could resupply the city as needed. Indeed, King Henry of Cyprus-Jerusalem (r. 1285-1324 CE) made it into the city this way on 4 May.

The knights of the military orders did make regular small-scale sorties in order to attack the enemy's flanks and occasional commando raids but without much success. One such night attack is here recorded by a young emir present at the siege, Abu'l-Fida:

A group of Franj [Latins] made an unexpected sortie and advanced as far as our camp. But in the darkness some of them tripped on the tent cords; one knight fell into the latrine ditches and was killed. Our troops recovered and attacked the Franj from all sides, forcing them to withdraw to the city after leaving a number of dead on the field. The next morning my cousin al-Malik al-Muzaffar, lord of Hama, had the heads of some of the dead Franj attached to the necks of the horses we had captured and presented them to the sultan. (Maalouf, 258)

By early May the defenders were in such reduced circumstances - there were barely enough men to man the whole length of the walls - that any sorties were stopped. King Henry offered to negotiate with Khalil, but the Sultan was only after total victory. By the second week of May, the attackers had undermined sections of the walls, eventually bringing about the partial collapse of several towers.

According to one contemporary account of the siege, the military commander or Marshal of the Knights Hospitaller, Brother Mathew of Claremont, was particularly valiant in defence of one of the breached gates:

Rushing through the midst of the troops like a raging man…he crossed through Saint Anthony's Gate beyond the whole army. By his blows he threw down many of the infidels dying to the ground. For they fled from him like sheep, whither they knew not, flee before the wolf. (quoted in Nicolle, 23)

Despite such smaller episodes of effective resistance, on 16 May the defenders were compelled to retreat behind the inner circuit wall. On 18 May, one final concentrated Mamluk assault began consisting of artillery fire, volleys of arrows and the cacophony of 300 drummers riding camels. As the historian T. Asbridge notes:

Mammoth in scale, unremitting in its intensity, this bombardment was unlike anything yet witnessed in the field of Crusader warfare. Teams of Mamluk troopers worked in four carefully coordinated shifts, through day and night. (653)

The devastating attack resulted in the Mamluk army breaking into the streets of Acre. Chaos and a massacre followed with the residents who could make it, fleeing for the few remaining ships that offered the only means of escape. There were not enough vessels to take everyone - although King Henry had managed to flee the scene unscathed - and there were unsavoury stories of some captains selling berths to the highest bidder. Those who were neither butchered nor ferried away to safety were taken prisoner and sold into slavery. There was one corner of the city, though, which fought on. In the south-west part of the city was the fortified quarters of the fanatical Knights Templars who knowing that for them defeat meant certain death, managed to resist against all odds for another ten days. When finally captured, the knights were executed, but there was a modicum of revenge when a portion of the unstable city walls collapsed and killed a number of the victors.

Khalil ordered the total destruction of the city's fortifications, removed bits and pieces of fine art and architecture for reuse in Cairo, and then moved on to take the few remaining pockets of Latin resistance in the Levant. Thus, by August 1291 CE, the cities of Sidon, Tyre, and Beirut, and the Templar castles of Tortosa and Athlit had all fallen. Thorough as ever, Khalil ordered the destruction of orchards and irrigation canals along the coast so that any future Crusading army would not benefit from them. The Latin East Crusader states which had been established in 1099 CE were no more.

Aftermath

The Knights Hospitaller were credited with helping many refugees escape to the safety of Cyprus, where the order established its new headquarters (before moving on to Rhodes in 1306 CE). The Knights Templar also made the island their new HQ, and it became the only Christian foothold in the region, along with Cilicia in the north of the Levant. There were two popular crusades in 1309 and 1320 CE and thereafter a few official crusades backed by the Popes and European kings, but there would be no direct attack on the Middle East. Instead, the Crusade ideal would be applied to other areas - where Christians were thought to be threatened or infidels considered ripe for conversion - such as the Baltic, Iberia, and central Europe.