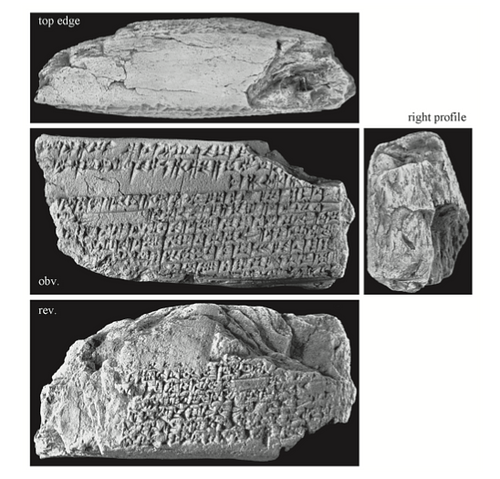

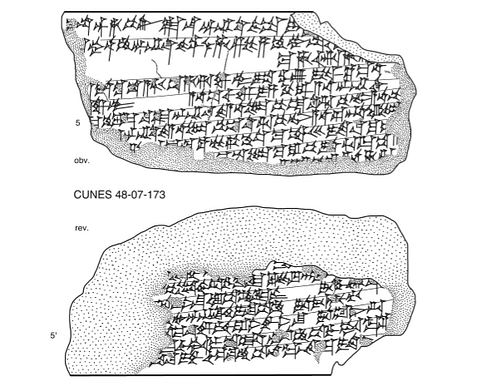

Sometimes it is the smallest discoveries that have the largest impact. When Alexandra Kleinerman and Alhena Gadotti found a new fragment of the Epic of Gilgamesh in 2015 CE, it did not seem to be particularly impressive. The broken tablet bore just 16 lines of text, most of it already known from other manuscripts. But working on the fragment, Andrew George discovered something remarkable. The structure of the new tablet did not fit our understanding of the epic. To get the fragment to make sense, whole episodes had to be moved around, yielding an entirely new sequence of events. One consequence of this was a new sex scene. The epic tells how the wild man Enkidu became human by having sex with a woman named Shamhat for an entire week, making love for six days and seven nights. But now it turns out that it took, not one, but two full weeks of love-making to make Enkidu truly human.

The world's largest jigsaw puzzle

The Epic of Gilgamesh is a Babylonian story about the eponymous hero Gilgamesh, the legendary king of the city of Uruk, in what is now Iraq. Thousands of years before Homer, the people of ancient Iraq composed poetry, debated the meaning of life, and studied the movement of the stars. These cultures – the Sumerian, Babylonian, and Assyrian – wrote their texts in the cuneiform script on tablets made of clay. Unlike the papyrus of the ancient Egyptians, clay can easily endure the passage of time, and so cuneiform tablets have survived in huge numbers. Archaeologists have uncovered around half a million texts written in cuneiform. But unbaked clay is also quite brittle, so the tablets usually do not come to us intact, but in bits and pieces. Today, philologists like Kleinerman, Gadotti, and George are hard at work piecing the fragments back together, but there is a long way to go. We are still just beginning to explore the treasure trove that is Babylonian literature.

The Epic of Gilgamesh is undoubtedly the most famous of these cuneiform texts. It is not, as is often claimed, the earliest known work of literature, in fact there are literary texts that are almost a thousand years older than the epic. But Gilgamesh is still a remarkable text. The fact that it continues to captivate readers from all the world, millennia after its original composition, tells you just how extraordinary the epic really is.

In the course of eleven tablets, we are told the story of Gilgamesh's friendship with the wild man Enkidu, and his failed search for immortality after Enkidu dies. As a young king, Gilgamesh is afflicted by a powerful restlessness. There is “a storm in his heart”, an abundance of energy that leads him to abuse the citizens of Uruk. Exhausted by his constant excess, the Urukeans pray for help. The gods decide to create Enkidu as a friend for Gilgamesh, hoping that the new playmate will keep the king occupied.

Enkidu grows up among the animals of the steppe, until one day he comes face to face with a hunter. Terrified by this savage creature the hunter asks his father what to do, and he is told to go to Uruk and present the problem to Gilgamesh. The king tells the hunter to bring a woman named Shamhat to the steppe. She will seduce Enkidu and thereby separate him from his animal companions. The hunter and Shamhat journey out into the wild, where they find Enkidu by a watering hole. Shamhat strips off her clothes and lures Enkidu into having sex with her for six days and seven nights. After this marathon of love, Enkidu finds that he has lost his raw animal strength, having instead gained the consciousness and intellect of a human being.

One or two scenes?

The Epic of Gilgamesh exists in a number of different versions. First, it was told as a cycle of independent poems in the Sumerian language. Then, the various threads of the story were woven together to form a single epic, in the Akkadian language. This is known as the Old Babylonian version, and it was composed c. 19th - 17th century BCE. Later, the epic was reworked, expanded, and updated to create what is known as the Standard Babylonian version. This is the version that is most often read today, and it was most likely composed around the 11th century BCE.

Sometimes the same episode is preserved in both an Old Babylonian and a Standard Babylonian version, allowing us to compare the different recensions. For example, Gilgamesh has two dreams that foreshadow his friendship with Enkidu, and though the gist of the episode is the same, the Standard Babylonian recension is more schematic and repetitive, as opposed to the livelier Old Babylonian text. Scholars used to think that the scene where Enkidu becomes human by having sex with Shamhat also existed in both an Old Babylonian and a Standard Babylonian version. Though there are slight differences between them, the sequence of events is essentially the same: the two make love for a week, and then Shamhat invites Enkidu to come to Uruk.

But the new tablet shows that this cannot be the case. The fragment gives us relatively little text, but it does provide us with a missing link between other, more fully preserved manuscripts. However, it joins these manuscripts in a way that is not at all what we expected. The new tablet contains both the end of the Old Babylonian episode, and the beginning of the Standard Babylonian one. Accordingly, the two episodes cannot be different versions of the same scene. Instead, both versions preserve one part of the same sequence: Enkidu and Shamhat have sex for a week, Shamhat invites Enkidu to Uruk, they have sex for a second week, and then Shamhat invites Enkidu to Uruk again.

How to be human

The discovery makes Enkidu and Shamhat's sexual marathon all the more impressive: two weeks of sex in a row is a daunting (if not unappealing) prospect. But the new tablet is also important for another reason. The two versions of the episode are slightly different, and since we now know these episodes to be part of the same story, the differences become all the more important.

In a nutshell, the differences between the two episodes reflect different stages of Enkidu's transition from an animal to a human being. The discovery allows us to study this transition in more detail: What does it mean to become human? What steps lead from a life among the animals to a full human consciousness? What did humanity entail for the ancient Babylonians?

The first time Shamhat invites Enkidu to come to Uruk she describes Gilgamesh as superb in strength and horned like a bull. Enkidu readily accepts her invitation, saying that he will come to Uruk – but only to challenge Gilgamesh and usurp his power. “I shall change the order of things”, he declares. “The one born in the wild is mighty, he has strength.” Though Enkidu has learned to plan and speak like a human being, his way of thinking is still very much that of a wild animal: he immediately sees Gilgamesh as an alpha male, a rival bull to be defeated. The only thing that matters to him at this point is strength and domination.

But the second time Shamhat invites him to Uruk, after they have had sex for yet another week, he sees things differently. Shamhat says that she will lead him to the temple, home of Anu, the god of heaven. Rather than change the order of things, Enkidu is to find a place for himself in society: “Where men are engaged in labours of skill, you, too, like a true man, will make a place for yourself.” Enkidu, now wiser after a second bout of civilizing sex, is ready to accept this invitation. “He heard her words, he consented to what she said: a woman's counsel struck home in his heart.” He has understood the value of urban life, accepting the fact that human society is not all about domination and strength, but also about cooperation and skill. Each human being is part of a larger social fabric, where everyone must find their own place.

What is interesting about this is that the epic tells that becoming human is a two-step process. First, one must learn to think like a human being, and second, one must learn to think like a member of society. After the first week of sex Enkidu may have acquired human language and a capacity for reflection, but he is still stuck in the world of animals: he thinks only in terms of challenging rivals and locking horns. To become fully human, he must learn to see himself not as an individual who has to assert his own strength, but as a social being who must participate in the life of the city.

A moving target

On a more general level, the new fragment is also a reminder of the epic's unique position within world literature. In a way, Gilgamesh is both the oldest and the newest member of the literary canon. It is the oldest work of literature that continues to be still widely read: The Old Babylonian version predates the Odyssey by roughly a millennium. But it is also constantly being updated, as new fragments come to light, forcing us to revise the text and produce new translations. We cannot hold out hope for a new snippet of the Iliad anytime soon, but Gilgamesh is still very much in flux, and its rediscovery is a work in progress. Almost 4,000 years after its earliest composition, the epic that we read continues to change and develop.

This is both exciting and frustrating. Each discovery brings new insights into the world of the epic and adds to our knowledge of Babylonian culture. The last time a new piece of Gilgamesh was uncovered, in 2014 CE, it brought us a new description of the Cedar Forest where Gilgamesh and Enkidu defeat the monster Humbaba. The Cedar Forest turned out to be a luscious jungle, full of tangled undergrowth, oozing resin, drumming monkeys, and a chorus of birds. But the fragmentary state of the epic also means that there are tantalizing moments in the story that, at least for now, remain unknown. The scene of Enkidu's death, halfway through the epic, is interrupted by a long break, as if to spare us the pain of witnessing his final agony.

I am currently preparing a new translation of the epic into Danish, in cooperation with my father, the poet Morten Sondergaard. When George published his study of the new fragment, I was faced with a situation that is quite unusual among translators: the text I was working on suddenly changed before my eyes, and I had to go back and rearrange my translation. Working with Gilgamesh is to tread on shifting ground, which is just one more aspect of the epic that makes it a source of unending fascination.