The best-known vision of the Norse afterlife is that of Valhalla, the hall of the heroes where warriors chosen by the Valkyries feast with the god Odin, tell stories from their lives, and fight each other in preparation for the final battle of Ragnarök, the end of the world and death of the gods. This image is as deeply associated with Norse beliefs from around the Viking Age (c. 790-1100 CE) as that of the Viking funeral in which a boat is decked out as a pyre with the corpse surrounded by treasures, and either buried or set on fire.

These descriptions come from works preserving Norse mythology and other types of literature (as well as physical evidence) which show that burying boats and ships as biers, or setting them on fire as pyres, did happen and such images have been popularized in media (most recently through TV series such as Vikings and The Last Kingdom). There were, however, a number of possible destinations for Scandinavian souls in the afterlife and boats, because they were so costly, seem to have been rarely buried or burned. A Viking – or any Scandinavian warrior – may have expected to wake up in Valhalla after death but the farmer or weaver who had never picked up a sword or axe would not. Even so, what precisely they would have expected is unclear.

Norse religion was fully integrated into the lives of the people and there was no one set of dogmatic beliefs on how the gods operated, how they were to be worshiped, or where the soul went to after death. Religious rituals were practiced privately in homes or at outdoor festivals and the Norse had no written scripture. It is difficult, therefore, to reconstruct Norse beliefs in the present day as they would have been enacted before and during the Viking Age.

Further, the Norse concept of the 'soul' was quite different from how it is understood in the present day or how it was by Christians in the 8th-12th centuries CE. The soul had four components and one's destination in the afterlife could range between continued existence in one's grave, haunting one's former home, one of the realms of the deities, or other possibilities.

Parts of the Soul

The Norse conception of the soul included four aspects which made up a whole person:

- Hamr – one's physical appearance which, however, would and could change. The hamr could be manipulated for shape-shifting, for example, or could change color after death.

- Hugr – one's personality or character which continued on after death.

- Fylgja – one's totem or familiar spirit which was unique to an individual and mirrored their hugr; a shy person might have a deer as their fylgja while a warrior would have a wolf.

- Hamingja – one's inherent success in life, seen as a quality (or protective spirit) which was both caused by a person's hugr and formed it; one's hamingja would be passed down through a family, for good or ill.

These parts of the soul may or may not have all gone to a single destination after death. There is evidence that the Norse believed in reincarnation where one's hugr would pass into the body of a newborn relative while one's hamingja continued on in the family at large and one's fylgja seems to have just ceased to exist at the person's death. There was no judgment by the gods involved in a soul's final destination; for the most part, it seems, a soul went wherever it went. The great hero-god Baldr goes to the grey land of Hel beneath the earth, not to Valhalla, and even the gods cannot bring him back. The Norse sagas themselves often contradict each other in presenting their view of the afterlife and the power of the gods.

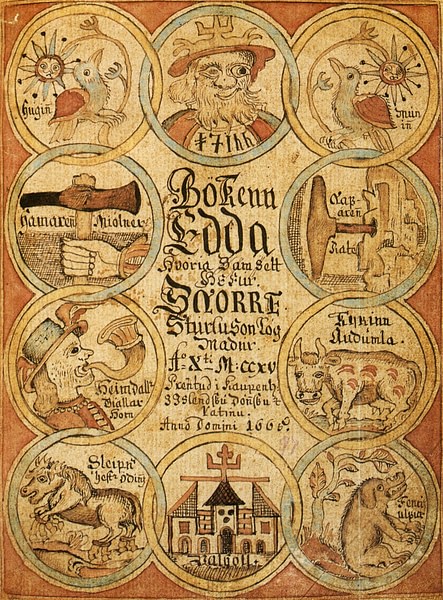

A difficulty in understanding Norse beliefs in the modern-day, as noted, is that Viking Age Scandinavians left us no written record (with the exception of inscriptions in runes, most importantly on runestones) until their interaction with and eventual spiritual conquest by Christianity (c. 10th-12th centuries CE). Prior to Christianity, Norse religion was transmitted orally but, afterwards, Norse Christians such as the Icelandic mythographer Snorri Sturluson (1179-1241 CE) wrote the changeable sagas and beliefs down in a structured way. Scholar Preben Meulengracht Sørensen writes:

The most important tool of the church was the book. This was revolutionary, as it made it possible to preserve and transmit knowledge from remote parts and times. Knowledge no longer depended on the comprehension and memory of individuals, and changeability was no longer, as in oral culture, a natural consequence of communication. (Sawyer, 222)

Writers like Sturluson preserved the Norse beliefs but omitted some details which survive from fragments of pre-Christian runic works, through physical evidence from graves, or are alluded to in other works from the Christian era. These omissions suggest to scholars that more specifics may have been altered, exaggerated, or omitted by later Christian scribes who found Norse beliefs and practices distasteful.

Realms of the Afterlife

This pattern holds in descriptions of the realms of the afterlife which were preserved by these scribes. It is probable that the dynamic, living religion of the Norse presented a more complete view but one can no longer tell because of the Christian lens through which most Norse beliefs were transmitted. Briefly, there were five possible destinations for a Norse soul after death:

- Valhalla

- Folkvangr

- Hel

- The Realm of Rán

- The Burial Mound

Valhalla – the hall of the heroes. When a Viking warrior died, the soul was believed to go to Odin's hall where he – or she – would meet old friends, talk and drink, and fight in preparation for the final battle of the gods at Ragnarok. Scholar H.R. Ellis Davidson writes:

In spite of Snorri's picture of an exclusively masculine Valhalla, there are grounds for believing that women too had the right of entry into Odin's realm if they suffered a sacrificial death. They too could be strangled and stabbed and burned after death in the name of the god. (150)

Folkvangr – 'The Field of the People' which was presided over by the fertility goddess Freyja. Little mention is made of Folkvangr in Norse tales but Freyja is usually depicted as benevolent, giving, and kind and so it is thought this realm would reflect her personality.

Hel – A grey land under the earth in the fog-world of Niflheim ruled by the goddess Hel and where the majority of souls would go. The realm of Hel has no correlation to the Christian conception of hell, but the goddess with the same name who personifies this realm is probably a Christian addition as for pre-Christian times belief in her is not attested.

The Realm of Rán – Sometimes alluded to as the Coral Caves of Rán. Rán was a giantess, married to Aegir the giant and Lord of the Sea, who lived at the bottom of the ocean. Rán's realm was illuminated by the massive treasure she had taken from sailors she had caught in her net and drowned and the souls of these sailors remained with her.

The Burial Mound – The soul of the deceased could also remain where the corpse was buried and was then known as a haugbui ('howe', a burial mound), a 'mound-dweller', who would not leave the grave. The soul could also remain in the area after death but left the mound to cause problems for the living. This entity was known as the draugr or as the aptrgangr (meaning 'after-goer' or 'again-goer'); i.e. 'one who walks after death'.

Two Types of Ghosts

The haugbui and draugr are the central ghost figures appearing in Norse literature. Other spirits mentioned are elemental entities or deities but the haugbui and draugr are the reanimated corpses of people – not ethereal spirits gliding over fields or down staircases but powerful supernatural beings in physical form who jealously guard their former possessions or terrorize their family or community.

The haugbui meant no one any harm unless their grave was disturbed. These souls were deeply attached to the area they were in and were content to stay there, as in the case of the warrior Gunnar Hamundarson from the Icelandic Njal's Saga (13th century CE). At one point, Gunnar is exiled for three years for a crime he is coerced into. He accepts his punishment and prepares to leave but, as he is walking away, he turns and looks back on his farm, realizes how much he loves it, and returns home.

Gunnar is later killed in an attack by the same enemies who had forced him into the earlier crime. He is buried with his goods in a mound on his property and one night the grave's door is found open. Gunnar is seen looking up at the moon and he “was merry, with a joyful face.” (Njal's Saga, ch. 78). The door in the mound-howe was for delivering food offerings to the soul because the dead were thought to be always hungry. A number of stories and legends include this detail of the open grave-door and the haugbui inside. H.R. Ellis Davidson writes:

There is mention of a door in the mound, so that men could enter it, and of wooden figures kept inside. The idea that the dead man rested inside his grave mound as in a dwelling is one found repeatedly in the Icelandic sagas…Sometimes we find the pleasant idea of friends buried in neighboring mounds conversing with one another. (154)

The haugbui was only dangerous if its mound (and grave goods) were threatened. The draugr, on the other hand, was malevolent and would leave the mound to wreak havoc – murdering people, killing animals, and destroying property. One of the best-known stories of a draugr comes from the Icelandic Grettir's Saga (13th-14th century CE). In this story, a farmer named Thorhall is having trouble keeping servants on his property; they keep leaving, claiming his place is haunted. He finally hires a tall heathen named Glam who says he has no fear of spirits and proves as good as his word as he takes care of the sheep and other tasks.

One Christmas Day, Glam is found dead in the fields (apparently because he ate meat on a fast-day the evening before). He is too heavy for the people to move easily and, besides, they want to celebrate; so his body is left out for a few days. When he is finally buried there is not much ceremony involved because he was a heathen, but he does not stay buried for long. Soon after, Thorhall has more trouble than before keeping help on his farm as Glam – now supernaturally tall and strong with skin “blue as hell” – goes about killing the flocks, breaking objects and house-riding (bouncing up and down while sitting on the roof).

One shepherd who agrees to work for Thorhall disappears and is found dead in the churchyard with his neck and all his bones broken. Another servant who has remained on the farm for years is found in the barn in a similar condition and Thorhall's livestock is killed and eaten. News of Thorhall's problems with the ghost eventually reaches the hero Grettir Asmundson who offers his services.

Grettir waits in the farmer's hall and, after a few nights, Glam appears. The hero and the draugr battle through the hall and then outdoors until Grettir cuts off Glam's head. Thorhall and Grettir then burn Glam's corpse and “thereafter they gathered his ashes into the skin of a beast and dug it down whereas sheep-pastures were fewest, or the ways of men” (Grettir's Saga, ch. 35). Thorhall then goes and tells his neighbors what has happened and where the ashes are buried so the spot can be avoided.

The story contains a number of motifs found in other stories about the draugr:

- Glam is not Christian and despises Christian precepts.

- He is not buried properly.

- He is a reanimated corpse of enormous strength and size.

- He feeds on animals and people.

- His skin is blue (sometimes draugrs are black or white or green).

- He can only be killed by having his head cut off.

- The ashes must be burned and either let to blow out to sea or buried away from people.

Stories such as this one often emphasized the importance of proper funerary rites by warning of the very real danger of creating a draugr when one could as easily have a gentle haugbui for a neighbor. If Glam had been buried properly, even though he was not of the Christian faith, he probably would have remained at rest.

This was not always the case, however. In the story of Hrapp from the Laxdæla saga (13th century CE), a good woman with a tyrannical husband observes all the proper burial rites and is still haunted by the man's draugr after his death. Hrapp demands he be buried in the living room of his house, upright, so that he can watch over all his possessions and servants. Even though this is done to his specifications, he still haunts the family and “killed most of his servants in his ghostly appearances” (Ch. 17). To end the hauntings, the family has to dig up his corpse and move it “away to a place near to which cattle were least likely to roam or men to go about” (Ch. 17).

After this is done, and without having to cut off Hrapp's head, the hauntings stop. This story would have given advice on how to deal with an unruly ghost but also emphasizes the importance of appreciating material objects without becoming obsessed with them. Unlike Gunnar, who loves his farm and possessions and is happy with them in the afterlife, Hrapp wants to continue to control what he had once possessed. Hrapp's insistence on maintaining control, instead of letting go, transforms him into an evil spirit and he epitomizes another common characteristic of the draugr: envy of the living and all they can still enjoy.

Conclusion

The popular image of the Viking warrior who scorns death, confident of a place at the tables of Valhalla, is contrasted by the view of death held by most Scandinavians in pre-Christian times who saw it as a tragedy. Death was the loss of all one had ever known and, if there even was such a thing as an afterlife, it was the dismal grey realm of Hel with its high walls and thick gates. Scholar Kirsten Wolf notes:

The eddic poem Havamal (Sayings of the High One), which is considered to express the sentiments of certainly a number of the common people in Norway and Iceland in the late Viking Age, scorns mystical beliefs, such as those in a future life. According to this poem, death is the greatest calamity that can befall a man; ill health and injury are better. Even a lame man can ride a horse, a handless man can drive herds, and a deaf man join in battle; it is better to be blind than burned on the funeral pyre. (214)

Further, as noted, there seems to have been no reason given for a soul to go to one realm rather than another after death, except in the case of Valhalla (and it is unclear how prevalent a belief in that realm really was). After the rise of Christianity in Scandinavian regions, the pagan afterlife was replaced by the vision of the Christian god's judgment and the realms of heaven, purgatory, and hell. According to Wolf, Christianity presented the Scandinavians “with a just and righteous god who was not subject to Ragnarok but ruling through eternity. It gave them firm answers to questions about death, life after death, and the purpose of it all” (223).

In time, Christian beliefs mingled with the earlier pagan precepts and, while people may have felt more confidence in where they were going after death, they still feared the dead who had gone before them. Funerary rites, such as bandaging the head of the corpse so it could not see where it was going to be buried (and so could not find its way back home) continued into the Christian era and the fear of the restless dead influenced the perpetuation of other similar rituals.

Christianity may have provided a more secure vision of the afterlife for the Norse but they still strongly believed there was no point in taking chances with ghosts. Images and talismans of Odin and Thor continued in use for protection from spirits well into the Christian period of Scandinavia, suggesting a reliance on the old ways of handling spirituality even as people accepted a new model of the afterlife.