Life for monks in a medieval monastery, just like in any profession or calling, had its pros and cons. While they were expected to live simply with few possessions, attend services at all hours of the day and night, and perhaps even take a vow of silence, monks could at least benefit from a secure roof over their heads. Another plus was a regular food supply which was of a much higher standard than the vast majority of the medieval population had access to. Besides attempting to get closer to God through their physical sacrifices and religious studies, monks could be very useful to the community by educating the youth of the aristocracy and producing books and illuminated manuscripts which have since proved to be invaluable records of medieval life for modern historians.

Development of Monasteries

From the 3rd century CE there developed a trend in Egypt and Syria which saw some Christians decide to live the life of a solitary hermit or ascetic. They did this because they thought that without any material- or worldly distractions they would achieve a greater understanding of and closeness to God. In addition, whenever early Christians were persecuted they were sometimes forced by necessity to live in remote mountain areas where the essentials of life were lacking. As these individualists grew in number some of them began to live together in communities, continuing, though, to cut themselves off from the rest of society and devoting themselves entirely to prayer and the study of scriptures. Initially, members of these communities still lived essentially solitary lives and only gathered together for religious services. Their leader, an abba (hence the later 'abbot') presided over these individualists – they were called monachos in Greek for that reason, which is derived from mono meaning 'one', and which is the origin of the word 'monk'. Over time, within this early form of the monastery, a more communal attitude to daily life developed where members shared the labour needed to keep themselves self-sufficient and they shared accommodation and meals.

From the 5th century CE the idea of monasteries spread across the Byzantine Empire and then to Roman Europe where people adopted their own distinct practices based on the teachings of Saint Benedict of Nursia (c. 480-c. 543 CE). The Benedictine order encouraged its members to live as simple a life as possible with simple food, basic accommodation and as few possessions as was practical. There was a set of regulations that monks had to follow and, because they all lived the same way, they became known as 'brothers'. Monastic rules differed between the different orders that evolved from the 11th century CE and even between individual monasteries. Some orders were stricter, such as the Cistercians which were formed in 1098 CE by a group of Benedictine monks who wanted an even less-worldly life for themselves. Women too could live the monastic life as nuns in abbeys and nunneries.

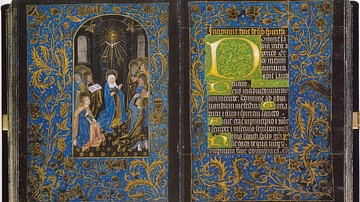

As monasteries were intended to be self-sufficient, monks had to combine daily labour to produce food with communal worship and private study. Monasteries grew in sophistication and wealth, greatly helped by tax relief and donations, so, as the Middle Ages wore on, physical labour became less of a necessity for monks who could now rely on the efforts of lay brothers, hired labourers or serfs (unfree labourers). Consequently, monks in the High Middle Ages were able to spend more time on scholarly pursuits, particularly producing such medieval monastic specialties as illuminated manuscripts.

Recruitment

People were attracted to the monastic life for various reasons such as piety; the fact that it was a respected career choice; there was the chance of real power if one rose to the top; and one was guaranteed decent accommodation and above average meals for life. The second or third sons of the aristocracy, who were not likely to inherit their father's lands, were often encouraged to join the church and one of the paths to a successful career was to join a monastery and receive an education there (learning reading, writing, arithmetic, and Latin). Children were sent in their pre-teens, often aged as young as five and then known as oblates, while those who joined aged 15 or over were known as novices. Both of these groups did not usually mix with full monks although neither oblates nor novices were ever permitted to be alone, unsupervised by a monk.

After one year a novice could take their vows and become a full monk, and it was not always an irreversible career choice as rules did develop from the 13th century CE that a youth could freely leave a monastery on reaching maturity. Most monks came from a well-off background; indeed, bringing a substantial donation on entry was expected. Recruits tended to be local but larger monasteries were able to attract people even from abroad. Consequently, there was never really any shortage of takers to join a monastery although monks only ever made up around 1% of the medieval population.

Monasteries varied in size with a small one having only a dozen or so monks and the larger ones having around 100 brothers. A major monastery like Cluny Abbey in France had 460 monks at its peak in the mid-12th century CE. The number of monks was essentially limited to the monastery's income which largely came from the land it owned (and which was given to it by patrons over the years). Monasteries included a good number of lay brothers in addition to the monks and these were employed to do manual labour such as agricultural work, cooking or doing the laundry. Lay brothers did observe some of the monastic regulations but lived in their own separate quarters.

The Abbot

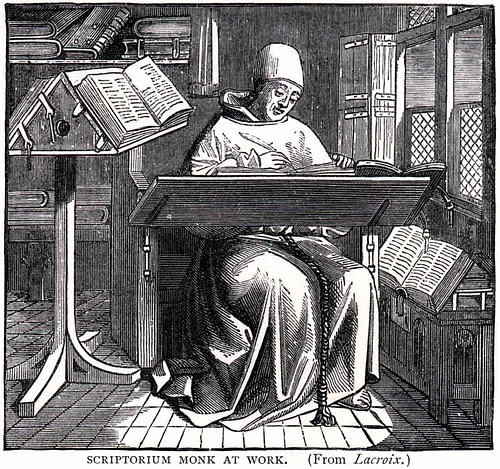

Monasteries were typically managed by an abbot who had absolute authority in his monastery. Selected by the senior monks, who he was supposed to consult on matters of policy (but could also ignore), the abbot had his job for life, health permitting. Not just a job for the old and wise, a monk in his twenties might stand a chance of being made abbot as there was a tendency to select someone who could hold the office for decades and so provide the monastery with some stability. The abbot was assisted in his administrative duties by the prior who himself had a team of inspectors who checked up on the monks on a daily basis. Smaller monasteries without an abbot of their own (but under the jurisdiction of another monastery's abbot) were typically led by the prior, hence the name of those institutions: a priory. Senior monks, sometimes known as 'obedientaries', might have specific duties, perhaps on a rotation basis, such as looking after the monastery's wine cellar, the garden, the infirmary, or the library and scriptorium (where texts were made).

The abbot represented the monastery when dealing with other monasteries and the state, in whose eyes he ranked alongside the most powerful secular landowners. Not surprisingly for such an important figure, monks were expected to bow deeply in the abbot's presence and kiss his hand in reverence. If an abbot were extremely unpopular and acted contrary to the order he could be removed by the Pope.

Rules & Regulations

Monks followed the teachings of Jesus Christ in rejecting personal wealth, as recorded in the Gospel of Mathew:

If you would be perfect, go, sell what you possess, and give to the poor, and you will have treasure in heaven; and come, follow me (19:21)

Along these lines, creature comforts were shunned but the strict application of such ideals really depended on each monastery. So, too, silence was a method to remind monks they were living in an enclosed society quite different from the outside world. Monks were generally not allowed to speak at all in such places as the church, kitchen, refectory or dormitories. One might be bold enough to attempt a snatch of conversation in the cloisters right after a general meeting but besides that indulgence, conversation was to be kept to an absolute minimum and when it did occur it was supposed to be restricted to ecclesiastical matters or everyday necessity. Monks were further restricted in that they could only talk to each other as speaking at all to lay brothers and novices was not permitted, not to mention to outside visitors of any kind. For this reason, monks often used gestures which they had been taught as novices and sometimes they even whistled rather than speak to a person or in a place they should not.

Anyone who had broken the rules was reported to the abbot; telling on one's brothers was seen as a duty. Punishments might include being beaten, being excluded from communal activities for a period, or even being imprisoned within the monastery.

Clothing & Possessions

Monks had to keep the tops of their heads shaved (tonsured) which left a distinctive band of hair just above the ears. In contrast to their hairline, a monk's clothes were designed to cover as much flesh as possible. Most monks wore linen underclothes, sometimes hose or socks, and a simple woollen tunic tied at the waist by a leather belt. Over these was their most recognisable item of clothing, the cowl. A monastic cowl was a long sleeveless robe with a deep hood. On top of the cowl another robe was worn, this time with long sleeves. In winter, extra warmth was provided by a sheepskin cloak. Made from the cheapest and roughest of cloth, a monk usually had no more than two of each clothing items but he did receive a new cowl and robe each Christmas.

A monk did not own very much of significance besides his clothes. He might have a pen, a knife, handkerchief, comb and a small sewing kit. Razors were only distributed at a prescribed time. In their own room, a monk had a straw- or feather mattress and a few woollen blankets.

A Monk's Daily Routine

Monks were not usually permitted to leave the monastery unless they had some special reason and were permitted to do so by their abbot. There were exceptions, as in Irish monasteries where monks famously roamed the countryside preaching and sometimes even founded new monasteries. For most monks, though, their daily life was entirely contained within the grounds of the monastery they had joined as a novice and which they would one day die in.

Monks usually got up with the sun so that could mean 4.30 am in summer or a luxurious 7.30 am in winter, the day being very much dictated by the availability of light. Beginning with a quick wash, monks spent an hour or so doing silent work, which for monks meant prayers, reading the text they had been assigned by their superior or copying a specific book (a laborious process that took many months). Next, morning mass was held, followed by the chapter meeting when everyone gathered to discuss any important business relevant to the monastery as a whole. After another working period, which might include physical labour if there were no lay brothers to do it, there was a midday mass (the High Mass) and then a meal, the most important of the day.

The afternoon was spent working again and ended around 4.30 pm in winter, which then saw another meal or, in the case of summer, a supper around 6 pm followed by more work. Monks went to bed early, just after 6 pm in winter or 8 pm in summer. They did not usually have an unbroken sleep, though, as around 2 or 3 am they got up again to sing Nocturns (aka Matins) and Lauds in the church. To make sure nobody was sleeping in the gloom one brother would go through the choir checking with a lamp. In winter they might not return to bed but perform personal tasks such as fixing and mending.

Monks were, of course, very poor as they had few possessions of any kind but the monastery itself was one of the richest institutions in the medieval world. Consequently, monks were well-catered for in the one area which probably mattered most to the majority of the population: food and drink. Unlike the 80% of those who lived outside monasteries, monks did not have to worry about going short or seasonal variations. They had good food all year round and their consumption of it was only really limited by how strict the rules of asceticism were in their particular monastery. In stricter monasteries, meat was not usually eaten except by the sick and it was often reserved for certain feast days. However, those monasteries with more generous rules allowed such meats as pork, rabbit, hare, chicken and game birds to appear on the communal dinner table more often. In all monasteries, there was never a shortage of bread, fish, seafood, grains, vegetables, fruit, eggs, and cheese as well as plenty of wine and ale. Monks typically had one meal a day in winter and two in summer.

Giving Back to the Community

Monks and monasteries did give back to the community in which they lived by helping the poor and providing hospitals, orphanages, public baths, and homes for the aged. Travellers were another group who could find a room when needed. As already mentioned, in education, too, monasteries played a prominent role, notably building up large libraries and teaching youths. Monasteries looked after pilgrim sites and were great patrons of the arts, not only producing their own works but also sponsoring artists and architects to embellish their buildings and those of the community with images and texts to spread the Christian message. Finally, many monks were important contributors to the study of history – both then and now, especially with their collections of letters and biographies (vitae) of saints, famous people, and rulers.