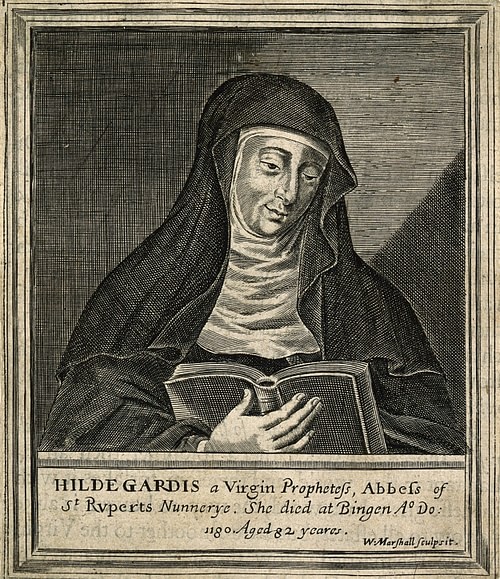

Monasteries were an ever-present feature of the Medieval landscape and perhaps more than half were devoted solely to women. The rules and lifestyle within a nunnery were very similar to those in a male monastery. Nuns took vows of chastity, renounced worldly goods and devoted themselves to prayer, religious studies and helping society's most needy. Many nuns produced religious literature and music, the most famous amongst these authors being the 12th century CE abbess Hildegard of Bingen.

Nunneries: Origins & Developments

Christian women who vowed to live a simple ascetic life of chastity in order to honour God, acquire knowledge and do charitable work are attested to from the 4th century CE if not earlier, just as far back as Christian men who led such a life in the remote parts of Egypt and Syria. Indeed, some of the most famous ascetics of that period were women, including the reformed prostitute Saint Mary of Egypt (c. 344-c. 421 CE) who famously spent 17 years in the desert. Over time ascetics began to live together in communities, although they initially continued to live their own individualistic lives and only joined together for services. As such communities became more sophisticated so their members began to live more communally, sharing accommodation, meals and the duties required to sustain the complexes which formed what we would today call monasteries and nunneries.

The monastic idea spread to Europe in the 5th century CE where such figures as the Italian abbot Saint Benedict of Nursia (c. 480-c. 543 CE) formed rules of monasterial conduct and established the Benedictine Order which would found monasteries across Europe. According to legend, Benedict had a twin sister, Saint Scholastica, and she founded monasteries for women. Such nunneries were often built some distance from monks' monasteries as abbots were concerned that their members might be distracted by any proximity to the opposite sex. Monasteries such as Cluny Abbey in French Burgundy, for example, prohibited the establishment of a nunnery within four miles of its grounds. Nevertheless, such separation was not always the case and there were even mixed-sex monasteries, especially in northern Europe with Whitby Abbey in North Yorkshire, England and Interlaken in Switzerland being famous examples. It is perhaps important to remember that, in any case, the medieval monastic life for men and women was remarkably similar, as the historian A. Diem here notes:

…medieval monastic life emerged as a sequence of “uni-sex” models. The long-lasting experiment of shaping ideal religious communities and stable monastic institutions created forms of monastic life that were largely applicable to both genders (albeit usually in strict separation). Throughout the Middle Ages, male and female monastic communities largely used a shared corpus of authoritative texts and a common repertoire of practices. (Bennet, 432)

Like male monasteries, nunneries were able to support themselves through donations of land, houses, money and goods from wealthy benefactors, from income from those estates and properties via rents and agricultural products, and through royal tax exemptions.

Convents

From the 13th century CE, there developed another branch of the ascetic life pioneered by male friars who rejected all material goods and lived not in monastic communities but as individuals entirely dependent on the handouts of well-wishers. Saint Francis of Assisi (c. 1181-1260 CE) famously established one of these mendicant (begging) orders, the Franciscans, which was then imitated by the Dominicans (c. 1220 CE) and subsequently by the Carmelites (late 12th century CE) and Augustinians (1244 CE). Women also took up this vocation; Clare of Assisi, an aristocrat and follower of Saint Francis, established her own all-female mendicant communities which are known as convents (as opposed to nunneries). By 1228 CE there were 24 such convents in northern Italy alone. The Church did not allow women to preach amongst the ordinary population so the female mendicants struggled to gain official recognition for their communities. In 1263 CE, though, the Order of Saint Clare was officially recognised with the proviso that the nuns remain inside their convents and follow the rules of the Benedictine order.

Monastic Buildings

A female monastery had much the same architectural layout that a male monastery had except that the buildings were laid out in a mirror image. The heart of the complex was still the cloister which ran around an open space and to which were attached most of the important buildings such as the church, the refectory for communal meals, kitchens, accommodation and study areas. There might also be accommodation for pilgrims who had travelled to see the holy relics the nuns had acquired and looked after (which could be anything from a slipper of the Virgin Mary to a skeletal finger of a saint). Many nunneries had a cemetery for nuns and another for lay people (men and women) who paid for the privilege of being buried there after a service in the nun's chapel.

Recruitment of Nuns

Women joined a nunnery primarily because of piety and a desire to live a life which brought them closer to God but there were sometimes more practical considerations, especially concerning aristocratic women, who were the principal source of recruits (much more so than aristocratic men were a source for monks). A woman from the aristocracy, at least in most cases, really had only two options in life: marry a man who could support her or join a nunnery. For this reason, nunneries were never short of recruits and by the 12th century CE they were just as numerous as male monasteries.

Young girls were sent by their parents to nunneries in order to gain an education – the best one available to girls in the medieval world – or simply because the family had such a number of daughters that marrying them all off was an unlikely possibility. Such a girl, known as an oblate, could become a novice (trainee nun) sometime in her mid-teens and, after a period of a year or so, take vows to become a full nun. A novice might also be an aged person looking to settle down to a contemplative and secure retirement or wanting to enroll simply to prepare themselves for the next life before time ran out. As with male monasteries, there were also lay women in nunneries who lived a slightly less austere life than full nuns and performed essential labour duties. There might also be hired female and even male labourers for essential daily tasks.

Rules & Daily Life

Most nunneries generally followed the regulations of the Benedictine order but there were others from the 12th century CE, notably the more austere Cistercians. Nuns generally followed the set of rules that monks had to but some codes were written specifically for nuns and sometimes these were even applied in male monasteries. The nuns were led by an abbess who had absolute authority and who was often a widow with some experience of managing her deceased husband's estate before she joined the nunnery. The abbess was assisted by a prioress and a number of senior nuns (obedientaries) who were given specific duties. Unlike monks, a nun (or any woman for that matter) could not become a priest and for this reason services in a nunnery required the regular visit of a male priest.

Virginity was an integral requirement for a nun in the very early medieval period because physical purity was considered the only starting point from which to reach spiritual purity. However, by the 7th century CE, and with the production of such treatises as Aldhelm's On Virginity (c. 680 CE), it was recognised that married women and widows could also play an important role in monastic life and that having the spiritual fortitude to live an ascetic life was the most important requirement of vowed women.

A nun was expected to wear simple clothing as a symbol of her shunning of worldly goods and distractions. The long tunic was typical attire, with a veil to cover all but the face as a symbol of her role as a 'Bride of Christ'. The veil hid the nun's hair which had to be kept cut short. Nuns could not leave their nunnery and contact with outside visitors, especially men, was kept to an absolute minimum. Even so, there were cases of scandal, such as in the mid-12th century CE at the Gilbertine Watton Abbey in England where a lay brother had a sexual relationship with a nun and, on discovery of the sin, was castrated (a common punishment of the period for rape, although in this case the relationship seems to have been consensual).

The daily routine of a nun was much like a monk's: she was required to attend various services throughout the day and say prayers for those in the outside world – in particular for the souls of those who had made donations to the nunnery. Generally, the power of a nun's prayer was regarded as equally efficient in protecting one's soul as a monk's prayer was. Nuns also spent a lot of time reading, writing and illustrating, especially small devotional books, compendiums of prayers, guides for religious contemplation, treatises on the meaning and relevance of visions experienced by some nuns, and musical chants. Consequently, many nunneries built up impressive libraries and manuscripts were not just for internal readers as many were circulated amongst priests and monks and even lent to lay people in the local community. One of the most prodigious such authors was the German Benedictine abbess Hildegard of Bingen (1098-1179 CE)

Unlike monks, nuns performed tasks of needlework such as embroidering robes and textiles for use in church services. The art was no trifle as at least one medieval nun was made a saint because of her efforts with a needle. Nuns gave back to the community through charitable work, especially distributing clothes and food to the poor on a daily basis and giving out larger quantities on special anniversaries. Lacock Abbey in Wiltshire, England (founded in 1232 CE by Ela, Countess of Salisbury), for example, gave out bread and herrings to 100 peasants on each anniversary of the founder's death. Besides giving out alms, nuns often acted as tutors to children, they looked after the sick, helped women in distress and provided hospice services for the dying. Nunneries thus tended to be more closely related to their local communities than male monasteries were and nunneries were often actually part of urban settings and less physically remote places. Consequently, nuns were perhaps much more visible to the secular world than their male counterparts.