The Battle of Stamford Bridge in Yorkshire, England on 25 September 1066 CE saw an army led by English king Harold II (r. Jan-Oct 1066 CE) defeat an invading force led by Harald Hardrada, king of Norway (r. 1046-1066 CE). Hardrada, aided by Harold's renegade brother Tostig, had managed to inflict a defeat on two English earls at the Battle of Fulford Gate a few days before, on 20 September, but Harold's army marched north to gain total vengeance, and both Hardrada and Tostig were killed at Stamford Bridge. Harold may have been victorious but his decision to promptly march south and face another invading army, this one led by William, Duke of Normandy (reigned from 1035 CE), would lead to catastrophe. At Hastings, on 14 October 1066 CE, Harold was killed and his army defeated, allowing the Normans to take over England.

Harold & The English Throne

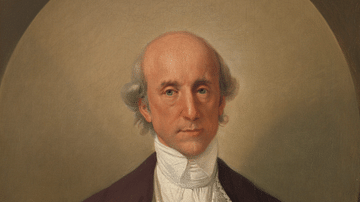

Harold Godwinson, Earl of Wessex, was made king on 6 January 1066 CE following the death of his brother-in-law King Edward the Confessor (r. 1042-1066 CE), who died childless. Harold had acquired the crown in unclear circumstances, although Edward, on his deathbed, had personally nominated Harold as his successor. Harold was the foremost military leader in the kingdom and had built his reputation on his successful campaigns in Wales in 1063-4 CE.

Going back to the events of two years earlier, in the spring of 1064 CE Harold was (possibly) sent on an unknown mission by Edward to the court of William, Duke of Normandy. The purpose may have been to inform William that he was the nominated successor to the English throne and pledge his loyalty to the Norman duke. Certainly, William would later claim that Edward had made such a promise back in 1051 CE. In alternative versions of events, Harold never went to Normandy at all or was merely blown off course and landed in France by accident. The English earl was then captured by Count Guy of Ponthieu and released only thanks to a payment from William, who then hosted Harold in his own court (or kept him a prisoner). William put Harold to good use in the Normans' battles with Duke Conan of Brittany where Harold fought bravely and earned the respect of his 'captors'. It was perhaps a condition of Harold's release from William's grasp that he had to promise William the throne of England or at least accept vassal status. That, at least, is the version presented by Norman writers.

Another take on events, presented in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, states that Harold only visited William's court to secure the release of a number of captured compatriots. To add another layer of interpretation on these murky happenings, the pro-Anglo-Saxon camp suggested that even if Harold did make a pledge of loyalty to William then, being at the time a captive, it was done under duress and so invalid.

In August 1066 CE, William, intent on enforcing his claim to the English throne, began extensive preparations for an invasion of England. A fleet was amassed on the northern coast of France near Saint-Valéry-sur-Somme. Harold knew of this impending invasion and prepared to meet it, but he had trouble keeping his own force together. The English army had already been in the field for over three months, and by harvest time men had to return to their farms where everyone was needed to ensure there would be enough corn for the coming year. Meanwhile, bad weather stalled William's plans - or he was cannily waiting for his opponents to disband - and Harold returned to London in the first week of September. Whatever the precise situation between Harold and William regarding the English throne and just where the invasion would strike became less of an immediate problem as there was now, in mid-September, suddenly an even more urgent threat to be faced: a full-scale invasion of northern England by Norway's King Harald Hardrada, aka Harald III.

Harold Hardrada

Hardrada would only play a cameo role in the Norman Conquest but many consider his decision to invade England at exactly the same time as William as the crucial factor in the ultimate demise of the Anglo-Saxons. Hardrada had an impressive military CV having spent years fighting as a mercenary for the Kievan Rus and, before that, in the elite Varangian Guard of the Byzantine Empire, famously helping capture from the Arabs both Messina and Syracuse on Sicily in 1038 CE.

Hardrada was aided by Tostig, the Earl of Northumbria, brother and great rival of Harold II. Tostig's harsh rule had caused a serious revolt in Northumbria in 1065 CE, and he was consequently stripped of his title and banished out of harm's way to Flanders. Tostig did not take this treatment well, and his ships harried the southern and eastern coasts of England. Escaping to Scotland, Tostig eventually ended up in Norway, where he saw Hardrada as the ticket to wresting the throne from his brother. In what must have been one of the most hotly contested thrones in history, Hardrada also laid claim to it. He had already unsuccessfully tried to enforce his claim to the throne of Denmark which, since 950 CE, had been receiving payments from English kings not to invade. The Danes had claimed sovereignty over large swathes of the country, and in the complex intertwined regional politics of England, Scandinavia, and Normandy, one of Edward the Confessor's immediate predecessors had been a Dane, King Cnut (aka Canute, r. 1016-1035 CE). Hardrada's dubious claim to the English throne had another, equally weak source, too, coming as an inheritance from his own predecessor, Sweyn (Swein) of Norway, who was an illegitimate son of Aelfgifu, wife of King Cnut.

Hardrada amassed a fleet of perhaps around 300 ships, although some estimates go as high as 500. Each Viking ship could, theoretically, have transported around 80 men including the rowers but an army as large as 24,000 would have been unlikely. Less than half that figure seems a much more probable number. The fleet sailed from Trondheim to Orkney and then moved south to land off the north-east coast of England near the mouth of the River Tyne on 8 September. There Hardrada was joined by a small fleet of perhaps 12 ships commanded by Tostig. From there the two fleets sailed south, stopping off to plunder Cleveland and then continuing down the coast to the mouth of the Humber River, up the River Ouse, and land at Ricall, just 16 km (10 miles) from the key city of York.

Battle of Fulford Gate

An Anglo-Saxon force of unknown size led by Eadwine, earl of Mercia, and Morcar, the earl of Northumbria, met the invaders at Fulford Gate, an uncertain location near York on 20 September. There are no contemporary historical records of the events of the battle, although it is mentioned in the Scandinavian sagas (epic poems) written two centuries later which are, like Snorri Sturluson's King Harald's Saga (part of the c. 1230 CE Heimskringla), unfortunately, packed with demonstrable inaccuracies, at least regarding the English history therein.

Both defenders and invaders were typically armed with a sword, large axe or long spear, and the better equipped (and front ranks) wore a chain mail coat. Further protection was provided by a conical helmet with a nose guard and a round or kite-shaped shield. There would have been some contingents of missile throwers who launched javelins, arrows, stone hammers, clubs and slingshots at the enemy before the other warriors moved forward as a unit with shields held close together to create a 'shield-wall'. The next stage would have been more chaotic, with small fighting groups and duels predominating. A common tactic was to use pairs of soldiers, one wielding with both hands a broad-bladed axe and another soldier with a sword and shield with the job of protecting the axeman who could not carry a shield.

While some historians believe the invaders had superior numbers, others assume that both forces at Fulford Gate were of a similar size if their respective commanders were willing to engage in open combat in a period when a single battle very often decided the fate of a kingdom. It may be that all of Hardrada's invasion force was not yet gathered in one place or a portion remained with the ships at Ricall. We do know that Hardrada and Tostig won the battle decisively, although quite why or how is not known for certain, except that both Eadwine and Morcar were in their twenties and inexperienced in large battles. Hardrada, on the other hand, was a seasoned commander in his fifties. The English earls may have been young but they did have the wits to escape the carnage and live to fight another day. The rest of the Anglo-Saxon army was not so fortunate and adding to the death toll from the battle itself, many of those warriors not killed by the enemy drowned as they were forced to retreat across the River Ouse.

When Harold, then in London, had received news of Hardrada's raids along the north-east coast around mid-September, he had immediately mustered his army, including his elite force of up to 3,000 housecarls (professional armoured troops) and then marched north, but he could not prevent Hardrada taking York in the meantime, the city capitulating without resistance on 24 September.

Stamford Bridge

Harold's army must have marched some 40 km (25 miles) a day to reach Tadcaster, 24 km (15 miles) from York, late on the 24th of September. The invaders were caught by surprise as Harold arrived, the English king selecting a wide meadow somewhere to the east of the River Derwent for the coming battle. Access to this handily flat area was via a wooden bridge known as Stamford Bridge, hence the name of the subsequent battle. Again, no details from contemporary records are available and the later sagas romanticise or simply invent many events. Two such famous episodes are the single Scandinavian warrior defending the bridge against impossible odds to allow Hardrada's reinforcements from Ricall time to gather and a personal meeting between Harold and Hardrada in which the former curtly told the latter he would concede only "7 feet of English soil". A more telling detail is the claim that Hardrada's men had the distinct disadvantage of being without their mail armour coats - they had left them in their camp following the victory celebrations after Fulford Gate and because they only expected to be negotiating hostages with the nobles of York that day (to ensure the city's loyalty). The last thing they expected was a full-on battle to decide the fate of England. It also seems likely that, caught by surprise, the invaders did not have time to form any battle plan or organise their troops properly.

More certain is the fighting was over within a day and both Hardrada and Tostig were killed. The battle was a complete victory for Harold with the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle recording that there were only enough survivors from the invading army to fill 24 ships, which sailed back home under the command of Hardrada's son, Olaf. The 13th-century CE chronicle The Life of King Edward notes that the fighting had been fierce and that the rivers were so full of corpses they "dyed the ocean waves for miles around with Viking gore" (Morris, 165). Tostig, despite his treachery, was buried with honour at York but the rest of the fallen were left to rot in the fields of Stamford Bridge, their bones still visible, according to some accounts, 50 years later.

As a footnote to the day's events, Hardrada, thanks to his more successful career prior to Stamford Bridge, subsequently had an entire cycle of sagas dedicated to him, in one of which is recorded (again a little fancifully) the poem he composed while dying:

We never kneel in battle,

before the storm of weapons

and crouch behind our shields;

so the noble lady told me.

She told me once to carry

my head always high in battle,

where swords seek to shatter

the skulls of doomed warriors.

(Bennet, 34)

Aftermath: William Conquers

Harold did not have a whole lot of time to celebrate his victory as, on 28 September 1066 CE, William and his invasion army landed at Pevensey in Sussex, southern England. The Normans would not have wondered where Harold was as they already had intelligence of Hardrada's invasion in the north. What William could not have known, though, was which king had won the battle of Stamford Bridge and who his opponent might be.

Then news came of the battle up north: Harold had won and was moving south as fast as he could to meet the Normans (significantly, the second forced march in a week). At Hastings, on 14 October 1066 CE, the superiority of the Norman cavalry against the Anglo-Saxon infantry, the slight advantage in numbers, and the tiredness of the Saxons ensured a victory for the invaders. Harold and other Saxon leaders, including the king's brothers Gurth and Leofwine, were killed. William the Conqueror, as he became known, was crowned William I, king of England on Christmas Day of the same year at Westminster Abbey, bringing an end to 500 years of Saxon rule. William, though, did have to struggle for five more years - winning battles against rebels in the north of England and building Norman castles everywhere - before he completely controlled his new realm.

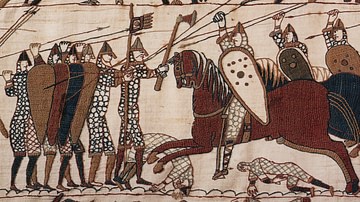

The Battle of Stamford Bridge is completely ignored by that great record of the Norman Conquest, the Bayeux Tapestry. Produced between 1067 and 1079 CE, the tapestry depicts in detail many aspects of the Norman Conquest and the events leading up to it but, as a propaganda piece, it is perhaps understandable that the crucial weakening of the Saxon army three weeks before at Stamford Bridge is carefully left out. Hastings might have forever eclipsed the Battle of Stamford Bridge into a footnote in history but the latter was responsible, perhaps more than any other factor, for the demise of both the Anglo-Saxons and the Vikings, ushering in a new era of history in northern Europe.