The medieval sources on the discovery and settlement of Iceland frequently refer to the explorers as “Vikings” but, technically, they were not. The term “Viking” applies only to Scandinavian raiders, not to Scandinavians generally. Some of settlers of Iceland may have been involved in Viking raids but they came to Iceland as farmers looking for a new start.

Unlike other regions colonized by the Vikings, Iceland had no indigenous population. When the Vikings struck the abbey at Lindisfarne in Britain's Northumbria in 793 or when they later raided in Wessex, Mercia, Ireland, or Scotland, they had to contend with those already living there. In Iceland, however, there was no one to conquer and no churches or abbeys to sack for portable wealth. The people who settled the land came initially from Norway (later from Orkney, the Shetlands, and Ireland) and were led by Norwegian aristocrats of considerable wealth who owned their own ships and could entice or command others to come with them.

The early history of the Scandinavians in Iceland is usually divided into three periods by modern scholars:

- The Age of Settlement, c. 870-930

- The Age of the Commonwealth, 930-1200

- The Age of the Sturlungs (or the Sturlung Age), 1200-1262

Christianity gained the upper hand in Iceland in c. 999/1000, replacing the Norse religion, but it is clear the majority of the people did not embrace the new faith willingly and it was more or less imposed on them by the Norwegian king Olaf Tryggvason (r. 995-1000) – who had forcibly converted Norway – and administered by the lawgiver Thorgeir Ljosvetningagodi (active c. 985-1001). According to scholar Robert Ferguson (among others), the half-hearted acceptance of Christianity in c. 999/1000 encouraged the violence and civil war that marked the Age of the Sturlungs, which ultimately resulted in the end of the commonwealth and Iceland's acceptance of Norwegian rule c. 1262.

The Age of Settlement

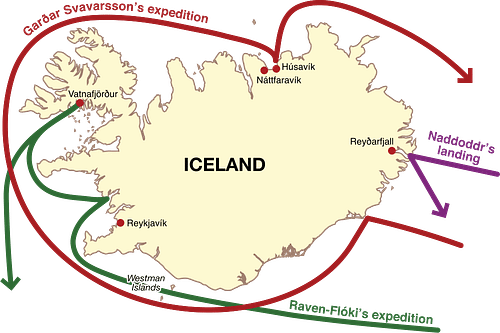

The earliest sources on Icelandic history are the Íslendingabók (“Book of the Icelanders”, c. 12th century) and the Landnámabók (“Book of the Settlements”, c. 13th century). According to the Landnámabók, the first settler in Iceland was Naddodd the Viking (c. 830) who discovered Iceland when he was blown off course en route to the Faeroe Islands.

He was followed later by Gardar the Swede (also known as Garðarr Svavarsson, c. 860s) who may also have been blown off course to Iceland. He established a small settlement on the shore of the bay of Skjálfandi (corresponding to the modern-day town of Húsavík), in the north. Gardar renamed the land “Gardar's Island” and sailed back home. One of his crew, however, a man named Nattfari, stayed behind with a slave and bondswoman. These three are said to have remained at the settlement on Skjálfandi Bay as the first permanent settlers.

The third, and best known, Scandinavian explorer to Iceland was Flóki Vilgerðarson (also known as Hrafna-Flóki, c. 868) who set out to deliberately colonize Iceland. Flóki stayed longer than the first two early explorers and established a community on the Borgarfjord (Borgarfjörður, on which lies the modern-day town of Borgarnes) on the west coast.

Ice blocking the fjord prevented Flóki from leaving and he was forced to stay much longer than he had planned. Prior to his departure he named the place “Iceland” and, upon his return to Norway, told everyone about the inhospitable land of ice and snow. Two members of his crew, however – Herjolf and Thorolf – praised Iceland, Thorolf going so far as to say it was so beautiful that butter dripped off the blades of grass. Their reports encouraged further migration from Norway to the new land which, in spite of Herjolf's and Thorolf's glowing praise, kept the name Flóki had given it.

Following Floki's return, interest in migration to Iceland rose tremendously in Norway. In the sources, not only the Íslendingabók and Landnámabók but works by Christian scribes, this is often attributed to the “tyranny” of the Norwegian king Harald Finehair (also known as Harald Fairhair, r. 872-930). Precisely what form this “tyranny” took is unclear but had something to do with the allocation of land and the high taxes imposed in Norway. A new land, where one could stake out a farm on a sizeable tract of land – without such taxes – would have seemed quite attractive.

The Landnámabók relates at length the tale of the first historical settler of Iceland, Ingólfr Arnarson (c. 874). Ingolfr and his foster-brother Hjörleifr were involved in a blood-feud in Norway and left for Iceland. They are said to have encountered Irish monks on the island who then left because they did not wish to live among the heathens. Hjörleifr and his party were killed by the slaves they had brought from Ireland and Ingólfr hunted the murderers down and killed them. Once his foster-brother had been avenged, Ingólfr founded the community which would become modern-day Reykjavík in 874.

Once a permanent settlement had been established, other colonists soon arrived. The Landnámabók records how, sometime around 927, when Iceland had been mostly settled, the people sent a man named Ulfljot back to Norway to develop a law code for Iceland based upon Norwegian laws. Ulfljot returned in 930 and delivered the law code to the Althing (the assembly of free men) of Iceland. By this time, Iceland had been divided into 36 principalities and each one had a chieftain representing them at the assembly to establish a peaceful and harmonious commonwealth.

The Age of the Commonwealth

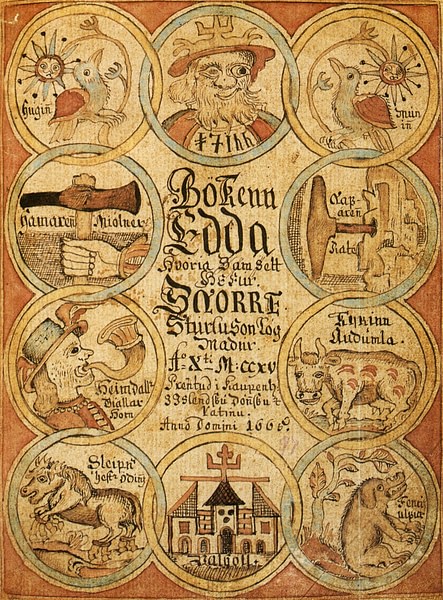

The early period of the Age of the Commonwealth (930-1030) is also known as “The Age of Saga” as this was the era in which most of the stories from the great Icelandic Sagas took place. These stories were passed down orally until the 12th- and 13th centuries when they were written down and include tales of the settlement of Iceland (the Íslendingabók and Landnámabók), as well as the famous The Saga of the Volsungs, The Saga of Ragnar Lothbrok, the Prose Edda, and the Poetic Edda which provided later generations with the knowledge of pre-Christian Norse beliefs and customs.

These accounts emphasize the equalitarian aspects of Norse society in that, although there was one chieftain of a tribe, decisions were made after consulting with advisors who represented the sometimes differing interests of the community. There were many separate communities along the coasts of Iceland known as communes. In each commune people lived by farming their own plot of land, raising cattle, fishing, hunting, and trading.

Each commune was led by five men elected for a one-year term. One of these five was sent as a representative to the Althing to settle disputes and regulate laws. Scholars Stefan Brink and Neil Price point out that “there is little doubt that the most important social institution in Iceland in the Middle Ages was the commune.” (574). This claim is accepted because each commune had its own identity but willingly cooperated with the others in matters of law to ensure equality and harmony between the communities.

Every spring and summer, the chieftain of each principality was sent to meet with the others at the Althing and vote on laws and various courses of action both religious and secular. Scholar Kirsten Wolf comments on the importance of law in Scandinavian society, writing:

That laws were important to Viking-age Scandinavians is beyond doubt. The modern English word “law” is an Anglo-Saxon loan of the Old Norse log (meaning “what was laid down or settled”). It would seem peculiar if the Anglo-Saxons borrowed such a word from a people that did not have a reputation for legal-mindedness. (150)

The Althing formed the basis for not only the law but also for cultural development within Iceland by maintaining harmony and balance between the communes. Icelandic government was an oligarchy, a “union of chieftains without a king” (Wolf, 151). The president of the Althing was the law-speaker who knew the law by heart and would recite it at the commencement of each gathering. The law-speaker served for a period of three years and then a new man was chosen. The laws in Iceland were communicated orally until c. 1117 when they were written down.

The Althing knew the law and mandated the law but had no power to enforce the law. Once a judgment was made, it was up to the individual to see that justice was done. The Althing could legislate land disputes and decide in favor of one farmer against another but had no power to make sure that decision was respected. Each individual was responsible, therefore, for upholding the decisions of the Althing and, as far as can be discerned, people did so. The Norse traditions of blood feuds and exacting a death for a death were replaced in Iceland by fines. Corporal punishment was replaced by the penalty of Outlawry by which a person was ostracized from the community.

These laws were based on communal religious beliefs and precedent as interpreted by the chieftains and the law-speaker. Wolf writes:

These chieftains had the title of godi (plural godar), a word that is derived from the Old Norse god (meaning “god”). The title therefore shows that the chieftains fulfilled both religious and secular functions. (151)

Peace was kept as long as everyone recognized the legitimacy of these laws and their sacred nature but this peace became increasingly threatened by Christian missionaries sent from Norway.

Christianity

According to the Kristni Saga (a 13th century account of the Christianization of Iceland), the first two Christian missionaries were a German named Fredrik (c. 981) and a Norwegian hand-picked by Olaf Tryggvason (prior to his ascent to the throne), Thorvald the Far-Traveler. Thorvald was so mercilessly taunted and ridiculed by the Icelanders that he killed two of them and had to flee back to Norway; Fredrik went with him.

After coming to power, Olaf sent another missionary band led by one Stefnir (c.997) who evangelized Iceland by destroying the temples and sacred shrines once he realized no one would be converted by his words. Scholar Robert Ferguson comments on the Icelanders' response to this, writing, “it is some indication of their alarm at Christianity's intolerant nature that, in a direct response to Stefnir's activities, the Icelanders now turned to the law to discourage the fanaticism of the followers of the new religion.” (300). Stefnir was outlawed and had to leave the country.

Olaf's next Christian representative was Thangbrand(c.999) who went the same route as Thorvald when ridiculed and killed two of his tormentors. He was also outlawed and returned to Norway. Olaf responded to his failure by confiscating the property of Icelanders in Norway and threatening to have them killed or maimed. He was talked out of this by two Icelandic Christian chieftains, Gissur Teitsson and his son-in-law Hjalti Skeggjason, who promised they would succeed where the others had failed. To make sure they did, Olaf secured four hostages, all related to the four most powerful Icelandic chiefs.

Upon their return, Gissur and Hjalti joined the others at the Althing where it shortly became clear that neither the Christians nor the pagans were willing to back down and some compromise had to be reached. The lawgiver Thorgeir Ljosvetningagodi, after meditating for 24 hours, delivered the verdict that everyone would become Christian and be baptized but pagans could still practice their faith in private.

This was done, as the Kristni Saga relates, to maintain unity because the zeal of the Christians was such that it threatened to break the country in half with pagan beliefs and laws governing one part and Christian ideals the other. Thorgeir seems to have felt that conversion to Christianity was inevitable in light of Olaf's determination but one must also consider how his decision was influenced by the hostages Olaf held and the possibility that he was bribed by one of the chieftains.

Whatever his motivation, the Icelanders submitted to his authority as law-speaker and converted to the new religion. Ferguson writes:

At the individual level, as travelers and traders, the conversion may have spared them the simple embarrassment of being old-fashioned in a modern world, country bumpkins clinging to outmoded ideas at the rim of the known world. Politically, it may have preserved their proud independence by averting the immediate threat of an invasion from Norway. (322)

Olaf Tryggvason died in 1000 and, in c. 1025, the Althing of Iceland negotiated a treaty with king Olaf Haraldsson of Norway (also known as Saint Olaf, Olaf II, r. 1015-1028) securing their personal rights and freedoms in Norway and autonomy in Iceland. Christian morality was now the underlying form for Icelandic law and the church grew in power, becoming highly influential in the development of new laws. The first written ecclesiastical laws of Iceland are dated to c. 1097 but were probably ratified much earlier and preserved orally, as the laws had always been.

The Age of the Sturlungs

Although the Althing was still convened, its activities were influenced by the Bishop of Iceland who presided from the Diocese of Skálholt. The first bishop was Ísleifur Gissurarson (served 1056-1080) and many others followed. The communes also continued to function as they had before only now observing Christian customs and traditions instead of those of the Norse religion. Instead of five elected men leading a commune, however, they were now led by a single chief and these chiefs, in time, amassed great power and wealth by adding other communes to their own.

Eventually, power ended up in the hands of six family clans, with the Sturlungs being the most powerful. In c. 1220, the Norwegian king Haakon Haakonsson (also known as Haakon the Old and Haakon IV, r. 1217-1263), became keenly interested in controlling Iceland and negotiated with the then-chieftain of the Sturlungs, Snorri Sturluson (c. 1179-1241), the great Icelandic mythographer and historian. Snorri agreed to become Haakon's vassal and vowed to work to bring the other chiefs under Norwegian influence, the goal finally being Norway's sovereignty over Iceland.

Snorri, for whatever reason, never made any attempt to fulfill his vow and it was taken up by his nephew Sturla Sighvatsson (l. 1199-1238). Sturla replaced Snorri as chieftain and initiated military campaigns against the other clans; Snorri was exiled back to Norway. Sturla and his father, the poet Sighvatr Sturluson (c. 1170-1238) engaged the clans of the Ásbirningar and Haukdælir families at the Battle of Örlygsstaðir in 1238 in which they were defeated and both killed. Gissur Thorvaldsson (1208-1268) of the Haukdælir clan and Kolbeinn ungi Arnórsson (1208-1245) of the Ásbirningar clan were now the two most powerful chieftains in Iceland and controlled the weaker clans and their communes.

Gissur then became a vassal of King Haakon Haakonsson of Norway and pushed the other chiefs to accept Norwegian sovereignty, too. In 1241, Snorri Sturluson returned from exile and Gissur, under orders from Haakon, led a team of warriors who killed the writer in his home. In c. 1242, Snorri's nephew Thordur kakali Sighvatsson (r. 1247-1250) returned to Iceland from Norway to avenge his uncle's death and also those of his father and brother at Örlygsstaðir. He fought Kolbeinn ungi Arnórsson to a draw in the naval Battle of Flóabardagi (Battle of the Gulf) in 1244 and defeated the forces of Kolbeinn's brother Brandur at the Battle of Haugsnes in 1246. Brandur was killed and the power of the Ásbirningar broken.

Thordur kakali Sighvatsson became the most powerful chieftain in Iceland and was also a vassal of Haakon of Norway. He and Gissur both appealed to the king to choose who would rule Iceland for him and Haakon chose Thordur; Gissur returned to Norway. In 1250, however, Haakon changed his mind and ordered Thordur to return to him. Gissur was sent back to Iceland in 1252 to encourage the chiefs to accept the terms of the agreement known as the Old Covenant establishing Norwegian sovereignty over Iceland, which was finally formalized between 1262-1264. Iceland would remain under Norwegian control until 1944.

Conclusion

The exact cause of the violence of the Age of the Sturlungs is unclear but some scholars suggest that it had to do with the forced conversion of the Icelanders from their traditional beliefs to a new faith. Ferguson, for example, writes:

This helpless spiral into barbarism may have been encouraged by the half-hearted abandonment of one set of cultural mores and values, and the imperfect and unconvinced adoption of another and very different set that led, over time, to a state of confused moral disorientation from which it proved too hard to recover. (323)

This conclusion is likely since Norse society under the old religion was centered on equality and all evidence indicates that early Iceland, pre-1000, followed this standard. It is only after the forced-adoption of Christianity that this paradigm changes and it seems this was encouraged by a new model where one man (the bishop) became the supreme authority in matters of religion and, therefore, law.

Norse polytheistic beliefs had room for any god who seemed worth worshipping – images and amulets invoking Jesus Christ were produced and worn alongside those of Thor's hammer – and there was no one deity considered better than another. Christianity's insistence on a single god and a single way of worshiping that god was as completely at odds with the Norse cultural ethos as the violence and imbalance of the Age of the Sturlungs was with Iceland's earlier days.