The Lycian Way follows over 540km (335 miles) of ancient roadways, mule tracks and shepherds' paths along one of Turkey's most remote and untouched coastlines. Theresa Thompson discovers the joys of following the trail and finding the ancient Lycians at the same time.

It was Lycia that clinched it for me. Or rather, the Lycians: an enigmatic Anatolian people who left behind them myriad massive free-standing and rock-cut tombs, and little else. And besides that, the thought of walking each day through the spectacular rocky countryside of south-west Turkey to discover ancient cities that remain today only as little visited archaeological sites, mostly unexcavated, and full of mystery.

Then, there was the teasing thought of a boat, a gulet, a beautiful traditional two-masted Turkish sailing boat. Friends had spoken of wonderful holidays cruising the Mediterranean's turquoise coasts, but prone to motion sickness and none too sure of the idea of life on a small boat, I'd shrugged that idea away. Not for me: I'd keep to adventures on land. But then, something clicked, and deciding that the only way to really know was to give it a go, I booked myself on a holiday with a title that promised Walking and Cruising the Lycian Shore.

Ah! The Lycian Shore: its magic had seeped into my consciousness years before from reading Freya Stark's book of that name. Known more for her travels in the Middle East and Afghanistan, and called by writer Lawrence Durrell 'the poet of travel', Stark (1893-1993) describing her 1950's voyage in the Elfin, spoke of swimming in secluded bays in waters that held light “like the star in a sapphire”, and mused on the histories and mysteries of the ancient citadels and sanctuaries she passed on a route that “continued to criss-cross with... ancient dramas.”

“Here is the source of all that has made us,” she said of Asia Minor.

It was beguiling. And now this trip promised something similar: archaeology, history, mystery, superb scenery, seas spangled with light and colour, exercise and relaxation.

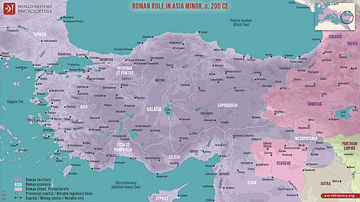

Lycia is a beautiful mountainous coastal region in south-west Anatolia (modern-day Turkey). In ancient times Lycia crops up in Greek mythology; as the Lukka Lands in Hittite and ancient Egyptian texts; and as people who originally came from Crete in the writings of Herodotus. In the Persian Wars, Lycians fought for the Persians and later came under their rule. In the Trojan War they were allies of the Trojans, and Homer's Iliad mentions two of their warrior leaders, Glaucus and Sarpedon, supposedly a son of Zeus.

The Lycians were said to be a fiercely independent people, and renowned naval raiders. Egyptian texts include them within a confederacy of 'Sea Peoples'. They were also culturally distinct. Whichever ostensible ruler, they retained a distinct identity with their own language and script. And unusually, according to Herodotus, they observed a matrilineal descent, the direct opposite of the Greeks who traced descent through the fathers. Conceivably a mark of the Lycians' individuality, they were the last people in Asia Minor to become part of the Roman Empire.

Our first walk took us up and around a ghost town that was occupied in Byzantine and Ottoman times and possibly built on or close to the site of an ancient Lycian town. Formerly called Levissi and known as Kayaköy today, in its more recent history, between 1922 and 1923, in an exchange of populations between Turkey and Greece, the Christians who lived there were made to leave at short notice for a new life in Greece.

It was a short walk, introducing us kindly to the rocky limestone terrain and forests of pine, cedar, and cypress that we would cross on this trip - the brochure labels the walking as 'intensive', and it is tougher at times – and we arrived at the bay where our gulet waited in plenty of time for the first of many delicious post-walk dips.

Tombs – those magnificent and near numberless ruins of assorted styles and sizes that mark out Lycian sites – were the focus of our second day's walk. Although the Lycians no longer exist as such and left little historical record, their tombs tell us a lot about them; from the way they treated their dead to their skill as stonemasons.

Climbing high above the Xanthos Valley, we reached a small plateau including the isolated farming village of Dodurga, which sits inside the larger ancient city of Sidyma. Its necropolis was our introduction to tombs in Lycia, although most here were actually from the Roman era. It turns out that most early buildings we were to see on this trip, from temples to theatres, were modified later in their histories to incorporate Hellenistic and Roman embellishments.

Strolling through the village it was clear that many of its buildings were built using stones recycled from the ancient city, and we spotted immense stone doorways still standing in gardens and outbuildings, and occasionally segments with ancient Greek inscriptions, of which one built into a corner of the village mosque listed the main gods and goddesses of Greek mythology. Some of the villagers had reused ancient tombs and Byzantine churches for storing goods or sheltering animals.

The Lycians took care designing their tombs. They had several types and the tombs frequently show Greek influences, and sometimes Persian. Perhaps the most striking are those carved into the living rock such as those at Pinara in the Xanthos valley.

Pinara was, at one point, one of the six principal cities of Lycia, and was certainly settled at least by the 5th century BCE, perhaps as one ancient writer suggests as an extension of the overpopulated city of Xanthos, the region's capital nearby. There is no Lycian site quite like it, I learn. Remote in its magnificent mountain setting, surrounded by pine forests and ancient olive trees, Pinara has never been systematically excavated – and for us, one of its glories was that it appeared to be little visited. Like many of the archaeological sites we explored, we had it virtually to ourselves.

A towering flat-topped acropolis, a veritable mountain, rises above the ancient city, its rusty red cliff face honeycombed by hundreds of simple rectangular tombs. It is an amazing sight. One theory I read suggested the Lycians may have believed that a mythical winged creature would carry them off into the afterlife; clearly, a cliff would facilitate this. If you have seen the Harpy Tomb in the British Museum you may recollect the reliefs of winged 'Sirens' (formerly thought to be Harpies) carved on the tomb's corners carrying tiny, presumed lifeless female figures in their arms.

First, we followed a path that led us to the so-called 'Royal Tomb' dramatically cut into the mountainside. With its splendid pediment and frieze, this has to have been made for an important ruler. It also has astonishingly detailed (though well-worn) reliefs in the porch depicting scenes of walled cities. They may show Pinara in its heyday for all we know, but even if generic they illustrate architectural details of Lycian homes, tombs and city fortifications.

Climbing up through the ruined city, along with more rock tombs we came across a building, perhaps a temple dedicated to Aphrodite that has unusual heart-shaped columns (and an enormous phallus in raised relief), also an odeon and agora (market place). In the lower acropolis, we picked our way along what was a shopping street over fallen columns and lintels from shop doors tumbled by earthquakes - frequent hereabouts - to reach the remains of a Byzantine church hanging on to the edge of a ravine. Then, winding our way downhill through the sweet-smelling pines we had our first view of the vast Greek-style theatre at the base of the city. It is stunning.

From the higher rows of the theatre, a place that once accommodated thousands of spectators we had breathtakingly beautiful views of the mountain, city and surrounding countryside. It was incredibly lovely and incredibly peaceful.

The Lycian landscape is dotted with free-standing tombs. Some turn up in odd places like in the middle of a road in a town as a traffic island; the pointed lids of some sarcophagi have the look of upturned boats, and others are like small stone houses. These 'house style tombs' are carved with protruding beams and sometimes have one or two stories. They are modelled on Lycian homes, and our tour leader, Peter Sommer, pointed out the similar construction of timber buildings in villages we passed through.

Tomb interiors are usually plain and may have several shelves. The sheer quantity and variety of Lycian tombs suggest some sort of cult of the dead. They did not build separate necropolises; their tombs were part of their lives. Gaping holes in many grave-chambers tell of raids in antiquity, perhaps soon after they were built (some have inscriptions and heads of Medusa warning off potential thieves), but there is evidence that the Lycians entombed their dead with a few everyday items and jewellery.

The Harpy Tomb mentioned above (not that we visited Xanthos on this tour) is an example of a pillar tomb - the marble chamber you see in the museum once sat atop a tall pillar. These are the oldest and least common form of tombs in Lycia and because of their ostentation were almost certainly used for important dynasts. We had seen the base of one pillar tomb at Sidyma, still standing sentinel over an ancient road that led in and out of the ancient city.

Toppled columns, stone lintels or pediments, and sarcophagi became familiar sights on our walks. Sometimes a sarcophagus might have carvings on it – a lion's head, a quadriga or four-horsed chariot, or seated human figures, for example - or a stone with a well-worn inscription that the classics scholars amongst us tried to translate (Lycian script isn't straightforward, adapted from the Greek alphabet but with added letters for sounds).

Other days we scrambled up to citadels, once to look across to the marshy site of the temple and fish oracle of Apollo (at Sura), one evening to the ancient city of Simena now crowned by a medieval castle and another time on a 16 kilometre-long ridge hike through forests of oak and strawberry trees from Phellos (the 'stony place'), a high citadel overlooking the Mediterranean, with incredible rock-cut house tombs. The unexpected became the norm. A giant carving of a bull, so indistinct you needed to be told where and how to look, and having scrambled over large boulders and bristly bushes, there was the reward of finding a recently discovered Roman mosaic.

On some days we followed parts of the Lycian Way, Turkey's first national long distance footpath. At 540 km long, it is rated as one of the world's top walking paths, but is very under-used this year as tourist numbers in Turkey have plummeted. In places it had become rather overgrown, if not impassable, but all day long we twisted and turned our way along it.

Many times we had to duck and dive our way through vegetation following Peter into hidden, abandoned temples and churches - all very Indiana Jones - but undaunted, we'd gamely agree this gave us a better workout!

Without a knowledgeable leader we would have missed many of these ruins, and certainly their significance. Some were barely visible amongst fallen stones and scrub until Peter would perhaps point out the curved remnants of the wall of a nave or some other manmade structure. Now and again we'd stand while he turned us into archaeologists, asking what we noticed about these ruins/stones/walls? What clues did a window arch give? Or who might have built this wall, was it Roman or earlier?

It was fun and interesting, though the trip was by no means all archaeology. Cruising along that gorgeous coastline was enough of a reason to go. And seasickness never really reared its head, though I stayed up on deck as much as possible. Even when a storm threatened it was okay, as we sheltered in a bay - along with other boats also taking refuge - it was the only time that our overnight stops were at all busy, other than in harbour. What archaeology we learnt came from easy and relaxed talks either during a break on a walk or at a site, or casually up on deck as we passed something interesting, such as when we cruised by the site of the Uluburun shipwreck, dated to the late 14th century BCE and discovered in 1982, during an underwater archaeological excavation that changed our understanding of what went on in the Late Bronze Age.

All in all, it was a superb experience. The sailing, the swimming in shimmering waters, a leatherback turtle paddling by, walking on rock and herb-strewn paths, the people - from our ship's four-man crew to the welcoming villagers sharing delicious warm flatbread straight from the oven, and pine honey! - and Turkey itself, its history, ancient and modern, mythological and archaeological, localised in a brief illuminating acquaintance with ancient Lycia.

“The past is our treasure,” Stark had written. Who can but agree? If you need an excuse for a journey such as this or such as hers, then, here you have it.

Images in this article were provided by Peter Sommer Travels. For more information about Peter Sommer Travels' Walking and Cruising the Lycian Shore visit: https://www.petersommer.com