In 378 CE the Tanukhid queen Mavia (r. c. 375 - c. 425 CE) of the Saracens led a successful revolt against the Roman Empire, pitting her forces against the armies under the emperor Valens (364-378 CE). Launching her insurrection from the region of southern Syria, she destroyed Roman territories in southern Jordan through modern-day Israel and Arabia.

The primary sources for her story are the Ecclesiastical History of Rufinus of Aquileia (c. 345-411 CE) who describes her in Book XI.6, Socrates Scholasticus (c. 380-439 CE) in his Ecclesiastical History Book IV.36, Theodoret of Cyprus (c. 393 - c. 458 CE) in his Ecclesiastical History Book IV.20, and Sozomen (c. 400-450 CE) in his Ecclesiastical History Book VI:38. A widespread revolt of the tribes of Arabia against Rome is also described in a work known as the Ammonii Monachi Relatio (dated to between c. 373-377 CE) which most likely describes Mavia's revolt of 378 CE and should be dated to that year.

While all of these historians provide more or less detailed descriptions of Mavia's insurrection, none of them provides a reason for it. All they say is how, after the death of her husband, she launched a successful revolt which forced Rome to sue for peace on her terms. She had only one demand: that a Christian monk named Moses be made bishop of her people.

This stipulation has suggested to some scholars that Mavia and her tribe were orthodox Nicene Arabian Christians who were objecting to Rome's plans to install an Arian bishop as their spiritual leader and so rebelled. In the book Christ in the Christian Tradition, for example, the scholar Aloys Grillmeier cites a rumor attributed to the cleric Theodorus Lector (d. c. 543 CE) that Mavia's tribe was Christian and goes on to state:

It seems likely, however, that at least some members of [Mavia's] tribe were Christians; how else can their desire for a bishop be explained? (34)

Scholar Irfan Shahid believes that Mavia's revolt needs to be understood within the context of “the ecclesiastical history of the period and its theological controversies” (152). In his Byzantium and the Arabs in the Fourth Century, Shahid focuses continually on the Christian aspect of the conflict as related in the primary sources and how the dispute between Mavia and Rome is related to the Arian heresy.

These claims ignore the complex nature of the 4th century CE in this region as well as the original accounts which record the rebellion. Nowhere in these accounts is it suggested that Mavia was a Christian and Sozomen, in fact, makes it clear that there were few Christians in her tribe even after Moses became bishop. Nowhere in any of the sources is it claimed that Valens planned to install an Arian bishop over Mavia's people. Further, it must be noted that the original sources are ecclesiastical histories which would surely have made mention of Mavia's Christianity if it had been a factor in the rebellion. The most likely cause of the revolt is not religious differences but Valens' breach of protocol.

The Saracens & Rome

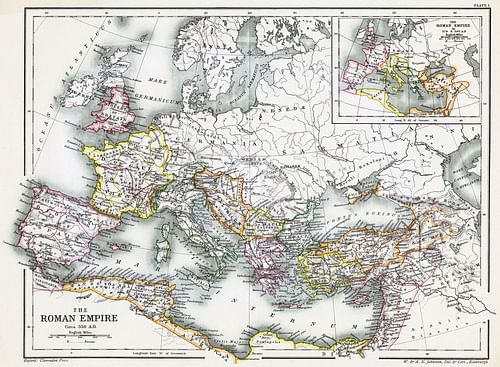

The Kingdom of Nabatea flourished in the region of ancient Jordan between 168 BCE and 106 CE; when it fell, the area was annexed by Rome as Arabia Petrea. The Nabateans had controlled the Incense Routes between Saba in southern Arabia and the Port of Gaza on the Mediterranean Sea even earlier (by at least 312 BCE) and were powerful enough to also exercise control over the Bedouin tribes of the area.

Among the tribes absorbed by the Nabateans were the Tanukhids who appear to have shared in their prosperity. Between c. 40 and 106 CE the Nabatean kings lost territory and power to Rome and their hold over the tribal coalitions relaxed. The Tanukhids became foederati of Rome but seem to have understood the agreement as existing only between their phylarch (“leader of the tribe”) and the emperor of Rome; their phylarch's successor – and by extension the people – had no obligation to continue service to Rome after the leader's death unless another agreement was reached.

The Gothic Wars

In the latter part of the 4th century CE, Rome needed as many foederati as they could muster against barbarian invasions and, during the reign of Valens especially, against the Goths. Valens engaged the Gothic king Athanaric (d. 381 CE) between 367-369 CE unsuccessfully and finally had to agree to terms as stipulated by the Goths.

Valens' conflict with Athanaric probably would have continued but for the intervention of the Huns who devastated the regions of the Goths and drove a number of them under the leadership of another Goth leader, Fritigern (d. 380 CE), across the border into Roman territories. The Goths had long been considered sub-human barbarians by the Romans, but, needing more and more men to fill their ranks, Goths had also regularly served as foederati fighting against their fellow Goths.

The Romans' poor opinion of the Goths finally resulted in the conflict known as the First Gothic War of 376-382 CE when Roman mistreatment of the Goths under Fritigern became intolerable. Fritigern led his people in an uprising and, in response, Valens mobilized the armies of Rome to put the Goth rebellion down.

Queen Mavia

It is at this point that Mavia enters history as Valens called upon his foederati to provide auxiliary troops for the army. Her husband had just died, and as noted, it does not seem that she recognized any formal agreement with Rome to supply them with troops. Socrates Scholasticus notes that Mavia began hostilities shortly after Valens had left Antioch, which most scholars place in c. 377 CE. Sozomen describes the rebellion and Rome's futile attempts to control it:

About this period, the king of the Saracens died and the peace which had previously existed between that nation and the Romans was dissolved. [Mavia], the widow of the late monarch, after attaining to the government of her race, led her troops into Phoenicia and Palestine, as far as the regions of Egypt lying to the left of those who sail towards the source of the Nile, and which are generally denominated Arabia. This war was by no means a contemptible one, although conducted by a woman. (Book VI:38)

When the Romans realized they could not defeat her, they sought terms and found Mavia had only one: she wished the monk named Moses from her region to be made bishop of her people.

The Orthodox-Arian Question

Her demand has led many to conclude that Mavia and her people were orthodox Nicene Christians who wanted an orthodox bishop, not an Arian, as their spiritual leader. At this time, there were two opposing Christian interpretations of who Jesus was. The orthodox Nicene interpretation claimed that Jesus was one with God the Father and the Holy Spirit and had never been created (a theological stance known as Homoosion meaning “one in being”) while the Arian interpretation held that Jesus was a created being, “begotten by the father”, and subordinate to him.

Arianism was first articulated by the cleric Arius (c. 256-336 CE) while the so-called orthodox interpretation was ratified by clerics under Constantine the Great (r. 312-337 CE) at the First Council of Nicaea in 325 CE. Constantine had defeated Maxentius, his rival as emperor, in 312 CE at the Battle of the Milvian Bridge and claimed his victory had been assured by a vision from the god Jesus Christ. If Jesus was only a man begotten of God then he was a demigod, not a full god, and Constantine had no patience with that interpretation. At the First Council of Nicaea, in fact, he threatened the bishops who would not condemn Arianism with exile or execution.

At the time of Mavia's uprising, Valens was an Arian as were a number of important bishops and clerics in Rome and throughout the provinces. To the orthodox Nicene Christians, Arianism was heresy because it denied the godhood of Jesus; to the Arians, the Nicene interpretation was polytheism as it maintained there was a godhead of three distinct and eternal entities. Orthodox Christians would have objected to being led by an Arian just as Arian Christians would have to an orthodox cleric leading them.

Mavia's demand, therefore, has understandably been interpreted in light of this controversy, and it would make sense that she was an orthodox Christian leading a tribe of orthodox Christians who refused to have an Arian bishop as spiritual leader. Some scholars (such as Shahid) have claimed that Rome wished to impose an Arian bishop on Mavia's Nicene Christian tribe and her objection took the form of a rebellion.

Although this interpretation would seem to make sense, it is not supported by the early accounts. The monk Moses is described as a member of Mavia's race who lived a blameless life and, through his faith in God, was able to perform miracles. It has been established that such monks evangelized the tribes of Arabia, not by proselytizing, but by example; their lives of selfless devotion to God drew others toward the Christian faith.

The Arabian tribes, like the Goths, were initially hostile to Christian missionaries because they believed – rightly – that Christianity was a Roman religion whose missionaries were sent to undermine their cultural values and traditions through conversion. Individual monks, however, who were not overt evangelists for the faith, seem to have been admired by the Arabs at this time and centuries later. They are sometimes referred to by the Arabic word rahib (plural: ruhban) which is translated as “overseer” in a spiritual sense.

The scholar Cenap Cakmak discusses rahib in this regard, interpreting it to mean “a person who devotes himself to intense worship” (1246). The ruhban were holy men whose faith transcended religious distinctions and divides and defined them as men of God, not as members of any particular organized religious system. Cakmak notes how this is apparent centuries after Mavia's revolt in passages of the 7th-century CE Quran:

The Quran depicts the priest (or monk) as a religious person who leads a secluded life most probably in a monastery without interfering in any political or daily matters. The depiction in the Quran also suggests that a priest spends his time performing rituals and prayers and stays away from sinful acts. (1245)

This type of religious figure would have been contrasted with the bishops and other clerics of Rome, who were frequently corrupt, engaged in various sordid affairs, and were members of a church hierarchy which had more to do with secular power than spiritual vision.

Mavia, then, could have been demanding that Rome use its power to persuade Moses to leave his solitary life as a monk and take on the responsibility of the spiritual leader of her people. She would have made this demand based on the innate goodness and spiritual power of Moses; not because she was an orthodox Christian.

Moses & the Peace Treaty

Unlike most of the monks in the Arabian region, Moses was an Arab. Shahid has noted that it may be his ethnicity that made him all the more impressive to Mavia and her people; he was one of their own. Moses was most likely an orthodox Christian as he is depicted as refusing to be ordained in Alexandria by the Arian bishop Lucius. The historian Michael the Syrian (d. 1199 CE) makes this claim, stating explicitly that Moses refused to be ordained by Arians. It may be, however, that Moses was objecting to Lucius personally, as a corrupt Christian cleric, rather than asserting doctrinal differences. Socrates Scholasticus describes the ordination of Moses and the conclusion of the peace treaty:

A person named Moses, a Saracen by birth, who led a monastic life in the desert, became exceedingly eminent for his piety, faith, and miracles. Mavia, the queen of the Saracens, was therefore desirous that this person should be constituted bishop over her nation, and promised on this condition to terminate the war. The Roman generals, considering that a peace founded on such terms would be extremely advantageous, gave immediate directions for its ratification.

Moses was accordingly seized, and brought from the desert to Alexandria, in order to be initiated in the sacerdotal functions: but on his presentation for that purpose to Lucius, who at that time presided over the churches in that city, he refused to be ordained by him, protesting against it in these words: “I account myself indeed unworthy of the sacred office; but if the exigencies of the state require my bearing it, it shall not be by Lucius laying his hand on me, for it has been filled with blood.” When Lucius told him that it was his duty to learn from him the principles of religion, and not to utter reproachful language, Moses replied, “Matters of faith are not now in question; but your infamous practices against the brethren sufficiently prove the inconsistency of your doctrines with Christian truth. A Christian is no striker, reviles not, does not fight; for it becomes not a servant of the Lord to fight. But your deeds cry out against you by those who have been sent into exile, who have been exposed to the wild beasts, and who have been delivered up to the flames. Those things which our own eyes have beheld are far more convincing than what we receive from the report of another.”

Moses, having expressed himself in this manner, was taken by his friends to the mountains that he might receive ordination from those bishops who lived in exile there. His consecration terminated the Saracen war; and so scrupulously did Mavia observe the peace thus entered into with the Romans, that she gave her daughter in marriage to Victor, the commander-in-chief of the Roman army. (IV.36)

The other accounts also credit Moses with concluding the peace between the Saracens and Rome. Sozomen does not mention Moses being ordained by bishops in exile, noting only that, after he refused to be ordained by Lucius, “he went to the Saracens” and further that “he reconciled them to the Romans and converted many to Christianity and passed his life among them as a priest, although he found few who shared in his belief” (VI.38).

Conclusion

Following the peace treaty, Valens was now free to deal with the Goth uprising. Mavia's revolt had delayed his deployment of troops in Thrace and he was now impatient to resolve the problems with the Goths. According to historian Ammianus Marcellinus (4th century CE), Valens was a vain man who refused to wait for reinforcements from the emperor Gratian (r. 367-383 CE) of the Western Roman Empire and foolishly launched an attack on a superior force. This claim is no doubt true, but it is also possible that Mavia's rebellion had delayed Valens so long, and had concluded so unsatisfactorily, that he felt he needed a major victory quickly to recover his prestige.

Valens met the Goths under Fritigern at the Battle of Adrianople where he was killed and the Roman army defeated in 378 CE. The Goth victory terrified the Romans who fortified their cities, including Constantinople, against attack. Ammianus notes how Saracen cavalry participated in the defense of Constantinople as foederati of Rome.

Peace with the Goths was concluded by Theodosius I (r. 379-395 CE) c. 382 CE and the terms were so favorable that they contributed to another uprising of the Tanukhids, who felt betrayed, in 383 CE. Precisely what these terms were is unclear but it seems that Mavia's coalition felt they had been treated unfairly in comparison. This revolt was crushed quickly, and Tanukhid power declined rapidly in the region afterwards. Another Arab tribal coalition, the Salihids, now became Rome's most important foederati in the province.

It has been suggested that Mavia might have been killed in the 383 CE revolt based on how quickly her tribe lost its prestige afterwards. This claim is speculative but so is the other, advanced by Shahid, that Mavia ruled until at least 425 CE. Until further evidence comes to light, Mavia's final fate remains a mystery. At the height of her power, however, it is clear she was a formidable warrior-queen who was able to challenge the legions of Rome and emerge victorious. It seems equally clear that her rebellion was not motivated by her alleged Christian faith but by her demand for respect as the reigning queen of her people.