By early 1070 CE William I (r. 1066-1087 CE) had almost completed the Norman conquest of England. There remained threats from the border regions with Wales and Scotland but the north of England had finally be subdued by the ruthless harrying of that region over the winter of 1069-70 CE. Unfortunately for William, there was one more serious challenge to his authority. This was the invasion of eastern England by an army led by the Danish king Sweyn II (r. 1047-1076 CE), and it gave the few remaining Anglo-Saxon rebels, led by Hereward the Wake, a last throw of the dice against the king's new Norman order in England. The focal point of this last rebellion was Ely Abbey in East Anglia but, like the numerous rebellions over the previous five years, William was victorious, and in the summer of 1071 CE the conquest was finally complete.

Consolidating the Conquest

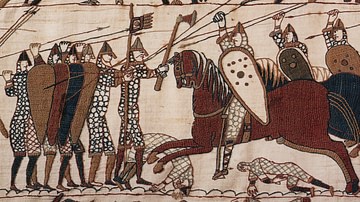

After the Battle of Hastings in October 1066 CE, William, the Duke of Normandy made short work of the south-east of England, quickly capturing Dover Castle, Canterbury, Winchester, and finally London. Crowned William I of England on Christmas Day, 1066 CE had been an excellent year for the Conqueror. Unfortunately, the next five years were much more troublesome. Two mini-invasions by Harold II' sons, who sailed from their retreat in Ireland to the west coast of England, were swept back, attacks from Wales were repulsed, and three rebellions based around York were finally stamped out by William's 'harrying of the north' - a sustained campaign of terror over the winter of 1069-70 CE when villages, crops, and livestock were torched to prevent any future rebellion. Loyal Norman nobles were eventually replacing all the old Anglo-Saxon elite, and motte and bailey castles were erected across the country to finally install some semblance of order. In 1071 CE, there remained, though, one final challenge to William's authority, a dangerous alliance of the few remaining Anglo-Saxon rebels and a Viking army led by King Sweyn II of Denmark.

The Danish Raid of 1069 CE

The Viking Danes had always exploited any trouble in England to launch raids and grab what booty and slaves they could. In addition, the Anglo-Saxon rebels had been calling for assistance in their efforts against William ever since his victory at Hastings. In September 1069 CE King Sweyn Estrithsson sent his brother, Asbjorn to lead a raid on the eastern coast of England. The Danish fleet consisted of around 300 ships and, at York, it linked up with the rebels and their figurehead, Edgar aetheling, great-nephew of Edward the Confessor (r. 1042-1066 CE). On 21 September, the castles of York were taken, the commanders ransomed off, and the ordinary troops massacred. William responded by marching at the head of an army to the north, but by the time he arrived the rebels had fled the city and the Danes had retreated down the River Trent with their extensive booty from York. Without a fleet of his own, William could not pursue the Danes and so he returned to the old policy of the Anglo-Saxon kings and paid them to leave English shores. It was to be only a temporary solution to the Danish threat as the raiders ignored their side of the bargain and remained in the impenetrable marshes of Lincolnshire over the winter. The Danes avoided all direct conflict, and it seemed this first invasion was really only intended to establish a bridgehead. The following year, Sweyn would be on English shores in person.

Hereward the Wake

In 1070 CE Asbjorn's Danish force had been depleted by the hunger and the cold of the harsh winter but they were now bolstered by the arrival of reinforcements led by Sweyn himself. The Danish king probably realised that the depleted force was now no longer sufficient to attempt a full-scale invasion but at least he could orchestrate a typical Viking raid and bring back home some booty. This looked an attractive possibility as, in May 1070 CE, Ely, then an island in the fens of East Anglia, had become the rallying point of the dying-but-still-smouldering Anglo-Saxon rebellion. Sweyn sent his brother to lead a force into the fens, where they linked up with a local nobleman Hereward the Wake who, like so many Anglo-Saxons, had lost his family estates to the new Norman overlords and was now reduced to living the life of an outlaw. Hereward, whose exploits are told in enriched tales of the later medieval period, was willing to fight to get his lands back again.

The joint rebel-Danish army marched on Peterborough in May/June 1070 CE, targeted, according to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, because William intended to appoint a new abbot at the abbey there, the Norman Turold of Fécamp (aka Turold of Malmesbury). The abbey itself was attacked and, despite valiant resistance from the monks, it was sacked and looted of its treasures and stored up wealth, the excuse being these riches should be kept from grasping Norman hands (and in truth William had been raiding other monasteries in 1070 CE to pay his armies). Hereward may have sought to use this treasure to pay an army to continue the resistance against William. In the event, the Danes promptly claimed the loot for themselves and, happy with their bounty, they made another pay-off deal with William and sailed off back home. In one of those delicious ironies of history and a tale of 'crime never pays', most of the Danish fleet and, with it, the treasure was sunk in a North Sea storm.

The loss of his Danish allies and his loot did not deter Hereward from fighting on, and he established his base at Ely Abbey from where he launched a sustained guerrilla campaign. Hereward was so successful that he began to attract the few remaining Anglo-Saxon rebels from across the country. By the first months of 1071 CE, numbers had swelled and included three big-name additions: Athelwine, the former bishop of Durham, Morcar, the former earl of Northumbria, and the on-off rebel who kept slipping in and out of favour with the king, Earl Waltheof. Now looking like a major rebellion might be organised, several small expeditions were sent by the king, including one led by the trusted commander William Malet, but all proved unsuccessful. The Conqueror was compelled to intervene personally.

William Fights Back

In the summer of 1071 CE, an army was mustered and a fleet assembled for a two-pronged attack on the rebels. The fleet approached from the east coast through the Wash and then sailed down the River Ouse, cutting off the abbey of Ely. Meanwhile, from the south-west, a land army marched from Aldreth (or Stuntney in the east in some sources), pushing across to Ely. William, overcoming the difficult terrain, made use of local knowledge to find a track through the marshes where he had to build a causeway to reach the island itself using timber and stones brought for the purpose. According to the most detailed (but often fantastical) source on the Ely rebellion, the 12th-century CE Gesta Herewardi, William also had the timbers and logs laid over inflated sheepskins to ensure the causeway could stay afloat (which it did not at the first attempt at crossing, drowning many men).

When the causeway was ready and the army crossed it, the king was presented with another problem. The abbey was built of stone and presented a formidable challenge to the attackers. Siege engines had to be brought in over the causeway and fortifications were set up to encircle the abbey. In the event, all these pre-attack preparations brought swift dividends, and the defenders, realising a long siege was about to get underway, either escaped in small boats or gave themselves up. Not for the first time, William's formidable military reputation combined with his meticulous attention to preparation and logistics had won him the situation without any actual fighting being necessary.

Many of those rebels unfortunate enough to be captured were mutilated or blinded, still more were imprisoned for life, including Athelwine and Morcar. On the other hand, Earl Waltheof settled with William, even marrying his niece Judith. Hereward escaped with a small group of rebels, later meeting his death at the hands of some Norman soldiers, or making peace with William, or living in exile on the Continent, depending on which medieval source you believe of this larger-than-life figure.

Aftermath

After Ely, William looked to the north. The king of the Scots, Malcolm III (r. 1058-1093 CE) had long been giving both refuge and military support to the Anglo-Saxon rebels and especially to Edgar aetheling, whose sister Margaret the king had married. In 1072 CE William, with England now free from rebels, could finally turn his attention to Scotland, and with a combined land and sea operation, he put a stop to the regular raids into Northumbria. Malcolm's submission was achieved and, as part of the peace bargain, Edgar was exiled to Flanders. William had finally secured both his realm and his place in history as one of the greatest of military commanders.