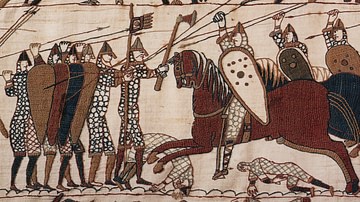

The Norman conquest of England, led by William the Conqueror (r. 1066-1087 CE) was achieved over a five-year period from 1066 CE to 1071 CE. Hard-fought battles, castle building, land redistribution, and scorched earth tactics ensured that the Normans were here to stay. The conquest saw the Norman elite replace that of the Anglo-Saxons and take over the country's lands, the Church was restructured, a new architecture was introduced in the form of motte and bailey castles and Romanesque cathedrals, feudalism became much more widespread, and the English language absorbed thousands of new French words, amongst a host of many other lasting changes which all combine to make the Norman invasion a momentous watershed in English history.

Conquest: Hastings to Ely

The conquest of England by the Normans started with the 1066 CE Battle of Hastings when King Harold Godwinson (aka Harold II, r. Jan-Oct 1066 CE) was killed and ended with William the Conqueror's defeat of Anglo-Saxon rebels at Ely Abbey in East Anglia in 1071 CE. In between, William had to more or less constantly defend his borders with Wales and Scotland, repel two invasions from Ireland by Harold's sons, and put down three rebellions at York.

The consequences of the Norman conquest were many and varied. Further, some effects were much longer-lasting than others. It is also true that society in England was already developing along its own path of history before William the Conqueror arrived and so it is not always so clear-cut which of the sometimes momentous political, social, and economic changes of the Middle Ages had their roots in the Norman invasion and which may well have developed under a continued Anglo-Saxon regime. Still, the following list summarises what most historians agree on as some of the most important changes the Norman conquest brought in England:

- the Anglo-Saxon landowning elite was almost totally replaced by Normans.

- the ruling apparatus was made much more centralised with power and wealth being held in much fewer hands.

- the majority of Anglo-Saxon bishops were replaced with Norman ones and many dioceses' headquarters were relocated to urban centres.

- Norman motte and bailey castles were introduced which reshaped warfare in England, reducing the necessity for and risk of large-scale field engagements.

- the system of feudalism developed as William gave out lands in return for military service (either in person or a force of knights paid for by the landowner).

- manorialism developed and spread further where labourers worked on their lord's estate for his benefit.

- the north of England was devastated for a long time following William's harrying of 1069-70 CE.

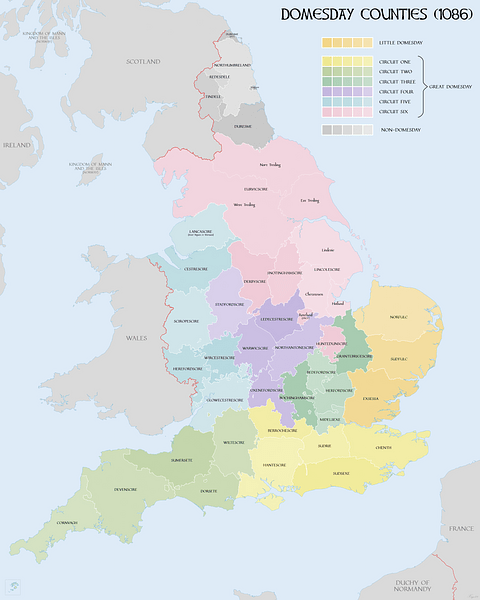

- Domesday Book, a detailed and systematic catalogue of the land and wealth in England was compiled in 1086-7 CE.

- the contact and especially trade between England and Continental Europe greatly increased.

- the two countries of France and England became historically intertwined, initially due to the crossover of land ownership, i.e. Norman nobles holding lands in both countries.

- the syntax and vocabulary of the Anglo-Saxon Germanic language were significantly influenced by the French language.

The Ruling Elite

The Norman conquest of England was not a case of one population invading the lands of another but rather the wresting of power from one ruling elite by another. There was no significant population movement of Norman peasants crossing the channel to resettle in England, then a country with a population of 1.5-2 million people. Although, in the other direction, many Anglo-Saxon warriors fled to Scandinavia after Hastings, and some even ended up in the elite Varangian Guard of the Byzantine emperors.

The lack of an influx of tens of thousands of Normans was no consolation for the Anglo-Saxon aristocracy, of course, as 20 years after Hastings there were only two powerful Anglo-Saxon landowners in England. Some 200 Norman nobles and 100 bishops and monasteries were given estates which had been distributed amongst 4,000 Anglo-Saxon landowners prior to 1066 CE. To ensure the Norman nobles did not abuse their power (and so threaten William himself), many of the old Anglo-Saxon tools of governance were kept in place, notably the sheriffs who governed in the king's name the districts or shires into which England had traditionally been divided. The sheriffs were also replaced with Normans but they did provide a balance to Norman landowners in their jurisdiction.

The Church was similarly restructured with the appointment of Norman bishops - including in 1070 CE, the key archbishops of Canterbury (to Lanfranc) and York (to Thomas) - so that by 1087 CE there were only two Anglo-Saxon bishops left. Another significant change was the move of many dioceses' headquarters - the main church or cathedral - to urban locations (Dorchester to Lincoln, Lichfield to Chester, and Sherborne to Salisbury being just some examples). This move gave William much greater administrative and military control of the Church across England but also benefitted the Church itself by bringing bishops closer to the relatively new urban populations.

The royal court and government became more centralised, indeed, more so than in any other kingdom in Europe thanks to the holding of land and resources by only a relatively few Norman families. Although William distributed land to loyal supporters, they did not typically receive any political power with their land. In a physical sense, the government was not centralised because William still did not have a permanent residence, preferring to move around his kingdom and regularly visit Normandy. The Treasury did, though, remain at Winchester and it was filled as a result of William imposing heavy taxes throughout his reign.

Motte & Bailey Castles

The Normans were hugely successful warriors and the importance they gave to cavalry and archers would affect English armies thereafter. Perhaps even more significant was the construction of garrisoned forts and castles across England. Castles were not entirely unknown in England prior to the conquest but they were then used only as defensive redoubts rather than a tool to control a geographical area. William embarked on a castle-building spree immediately after Hastings as he well knew that a protected garrison of cavalry could be the most effective method of military and administrative control over his new kingdom. From Cornwall to Northumbria, the Normans would build over 65 major castles and another 500 lesser ones in the decades after Hastings.

The Normans not only introduced a new concept of castle use but also military architecture to the British Isles: the motte and bailey castle. The motte was a raised mound upon which a fortified tower was built and the bailey was a courtyard surrounded by a wooden palisade which occupied an area around part of the base of the mound. The whole structure was further protected by an encircling ditch or moat. These castles were built in both rural and urban settings and, in many cases, would be converted into stone versions in the early 12th century CE. A good surviving example is the Castle Rising in Norfolk, but other, more famous castles still standing today which were originally Norman constructions include the Tower of London, Dover Castle in Kent, and Clifford's Tower in York. Norman Romanesque cathedrals were also built (for example, at York, Durham, Canterbury, Winchester, and Lincoln), with the white stone of Caen being an especially popular choice of material, one used, too, for the Tower of London.

Domesday, Feudalism & the Peasantry

There was no particular feeling of outraged nationalism following the conquest - the concept is a much more modern construct - and so peasants would not have felt their country had somehow been lost. Neither was there any specific hatred of the Normans as the English grouped all William's allies together as a single group - Bretons and Angevins were simply 'French speakers'. In the Middle Ages, visitors to an area that came from a distant town were regarded just as 'foreign' as someone from another country. Peasants really only felt loyalty to their own local communities and lords, although this may well have resulted in some ill-feeling when a lord was replaced by a Norman noble in cases where the Anglo-Saxon lord was held with any affection. The Normans would certainly have seemed like outsiders, a feeling only strengthened by language barriers, and the king, at least initially, did ensure loyalties by imposing harsh penalties on any dissent. For example, if a Norman were found murdered, then the nearest village was burnt - a policy hardly likely to win over any affection.

At the same time, there were new laws to ensure the Normans did not abuse their power, such as the crime of murder being applied to the unjustified killing of non-rebels or for personal gain and the introduction of trial by battle to defend one's innocence. In essence, citizens were required to swear an oath of loyalty to the king, in return for which they received legal protection if they were wronged. Some of the new laws would be long-lasting, such as the favouring of the firstborn in inheritance claims, while others were deeply unpopular, such as William's withdrawal of hunting rights in certain areas, notably the New Forest. Poachers were severely dealt with and could expect to be blinded or mutilated if caught. Another important change due to new laws regarded slavery, which was essentially eliminated from England by 1130 CE, just as it had been in Normandy.

Perhaps one area where hatred of all-things Norman was prevalent was the north of England. Following the rebellions against William's rule there in 1067 and 1068 CE, the king spent the winter of 1069-70 CE 'harrying' the entire northern part of his kingdom from the west to east coast. This involved hunting down rebels, murders and mutilations amongst the peasantry, and the burning of crops, livestock, and farming equipment, which resulted in a devastating famine. As Domesday Book (see below) revealed, much of the northern lands were devastated and catalogued as worthless. It would take over a century for the region to recover.

Domesday Book was compiled on William's orders in 1086-7 CE, probably to find out for tax purposes exactly who owned what in England following the deaths of many Anglo-Saxon nobles over the course of the conquest and the giving out of new estates and titles by the king to his loyal followers. Indeed, Domesday Book reveals William's total reshaping of land ownership and power in England. It was the most comprehensive survey ever undertaken in any medieval kingdom and is full of juicy statistics for modern historians to study such as the revelation that 90% of the population lived in the countryside and 75% of the people were serfs (unfree labourers).

A consequence of William's land policies was the development (but not the origin of) feudalism. That is, William, who considered all the land in England his own personal property, gave out parcels of land (fiefs) to nobles (vassals) who in return had to give military service when required, such as during a war or to garrison castles and forts. Not necessarily giving service in person, a noble had to provide a number of knights depending on the size of the fief. The noble could have free peasants or serfs (aka villeins) work his lands, and he kept the proceeds of that labour. If a noble had a large estate, he could rent it out to a lesser noble who, in turn, had peasants work that land for him, thus creating an elaborate hierarchy of land ownership. Under the Normans, ecclesiastical landowners such as monasteries were similarly required to provide knights for military service.

The manorial system developed from its early Anglo-Saxon form under the Normans. Manorialism derives its name from the 'manor', the smallest piece of land which could support a single family. For administrative purposes, estates were divided into these units. Naturally, a powerful lord could own many hundreds of manors, either in the same place or in different locations. Each manor had free and/or unfree labour which worked on the land. The profits of that labour went to the landowner while the labourers sustained themselves by also working a small plot of land loaned to them by their lord. Following William's policy of carving up estates and redistributing them, manorialism became much more widespread in England.

Trade & International Relations

The histories and even the cultures to some extent of France and England became much more intertwined in the decades after the conquest. Even as the King of England, William remained the Duke of Normandy (and so he had to pay homage to the King of France). The royal houses became even more interconnected following the reigns of William's two sons (William II Rufus, r. 1087-1100 CE and Henry I, r. 1100-1135 CE) and the civil wars which broke out between rivals for the English throne from 1135 CE onwards. A side effect of this close contact was the significant modification over time of the Anglo-Saxon Germanic language, both the syntax and vocabulary being influenced by the French language. That this change occurred even amongst the illiterate peasantry is testimony to the fact that French was commonly heard spoken everywhere.

One specific area of international relations which greatly increased was trade. Before the conquest, England had had limited trade with Scandinavia, but as this region went into decline from the 11th century CE and because the Normans had extensive contacts across Europe (England was not the only place they conquered), then trade with the Continent greatly increased. Traders also relocated from the Continent, notably to places where they were given favourable customs arrangements. Thus places like London, Southampton, and Nottingham attracted many French merchant settlers, and this movement included other groups such as Jewish merchants from Rouen. Goods thus came and went across the English Channel, for example, huge quantities of English wool were exported to Flanders and wine was imported from France (although there is evidence it was not the best wine that country had to offer).

Conclusion

The Norman conquest of England, then, resulted in long-lasting and significant changes for both the conquered and the conquerors. The fate of the two countries of England and France would become inexorably linked over the following centuries as England became a much stronger and united kingdom within the British Isles and an influential participant in European politics and warfare thereafter. Even today, names of people and places throughout England remind of the lasting influence the Normans brought with them from 1066 CE onwards.