While Oman is perhaps the most mysterious corner of the Arabian peninsula to Westerners, the country retains a strong sense of identity, a pride in its ancient past, and unique surprises in the domain of cultural heritage. In this exclusive interview, James Blake Wiener of Ancient History Encyclopedia (AHE) speaks to Mr. Tony Walsh - the author of The Land of Frankincense - about the country's varied landscapes and rarified cultural treasures.

JBW: While most people do not immediately associate the Middle Eastern nation of Oman with prehistoric and ancient sites, the country has a long and varied past, stretching back over 100,000 years. Arabs, Persians, Turks, the Portuguese, and Zanzibaris have all shaped Oman's culture and history.

Tony, you have lived in Oman for over two decades; what has kept you living in the country?

TW: I particularly enjoyed the experience of living in a different culture from my own and the opportunity to explore a country which offered me a constant stream of interest.

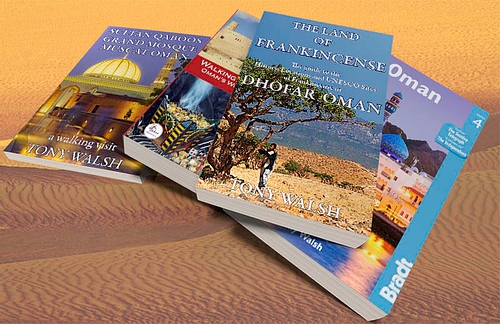

JBW: Your latest travel guide — The Land of Frankincense — explores the Dhofar Governorate in the south of Oman as well as four of the country's five UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

What differentiates this region from others in Oman, and why are so many cultural treasures located in Oman's far south? Please tell us about the monsoons that make southern Oman verdant and relatively cool during the summer season.

TW: The regularity of the almost clockwork arrival of the rain brought by the monsoon is what makes Dhofar unique in the Arabian peninsula. The coastal mountains have a dual effect on the local climate in littoral Dhofar. They block and concentrate the effect of the cloud bearing monsoon winds from the southwest and also act as a barrier to the hot desiccating winds of the Rub Al Khali Desert, immediately to the mountain's north. Rain does fall elsewhere on the peninsula but with the almost clockwork-like arrival of the monsoon's rain, ancient man could plan his movements to hunt animals, knowing where they would be.

Agriculture planting and harvesting could also be planned to take advantage of the precipitation. An added bonus to the monsoon is that while temperatures in most of the Arabian peninsula rise to over 50° C (122° F), in Dhofar the temperature fluctuates between 20-30° C (68-86° F). Most remarkably the effects of a predictable seasonal change in wind direction from the northeast to southwest in the Arabian Sea allows long-distance sea voyages to be organised with a predictable date of return. I feel that it is this combination of benign climate and ability to travel through the monsoon which enabled man to develop a cultural base in Dhofar that we can enjoy today.

There are several historic trading towns along the coastline here, perhaps the forerunner of these is Samharam which flourished between the 3rd century BCE and 5th century CE. This period was one of growth in the Frankincense trade and Samharam developed as a walled trading town located within a superb natural trading harbour. It was established before the Roman–Indian direct trade started and as this trade grew Samharam became a beneficiary of it.

JBW: Aside from those sites in Dhofar highlighted in your last title, what other ancient sites would you recommend to visitors in Oman? Moreover, do you have a favorite ancient or medieval site that you find particularly evocative? If so, which one, and why?

TW: Although my book focuses on Dhofar's "Land of Frankincense," northern Oman, with its man-made oasis culture and remains of an ancient copper mining civilisation, also has a wealth of little known archaeological sites. For a casual visitor this region's historic forts are the dominant historic monument; indeed it would be fair to say that any settlement of more than a few dozen houses would have some type of fortification.

More interesting is Oman's ancient man-made irrigation channels, the aflaj, which in origin date back at least 2,500 years. This water system enabled man to flourish in a desert climate and has also directly impacted the cooperative human culture in Oman as the system is very labour and capital intensive to construct.

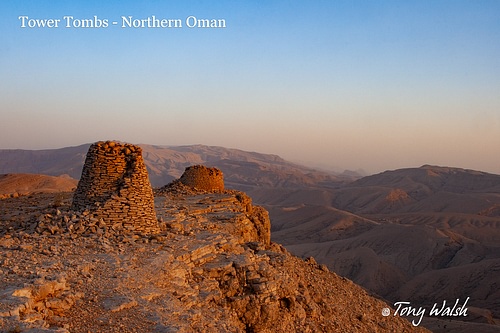

However, for me, perhaps the most evocative ancient site in Oman are a number of cairn tombs, which in this region are usually referred to a "beehive tombs" because of some similarity to the northwest European "skep" beehives. Perched on the edge of a cliff at 1800 m (5906 ft) are a cluster of these tombs, which have been dated to 3500-2000 BCE. Their extraordinary location overlooking low hills and a sand desert in the distance create a sense of evocative drama, presumably the reason their builders chose such an inaccessible location to not only build these tombs, but also bury their dead in them, although they must have lived in the valleys below.

JBW: I would be curious to know more about the importance of the Frankincense tree in Oman — where and how does it grow? Is it an essential element in Omani culture and identity?

TW: The Frankincense tree, Boswellia sacra, grows in the Dhofar Mountain range in southern Oman. Surprisingly it grows throughout these mountains, from the cloud covered cliffs that drop into the Arabian Sea to desiccated valleys which lead into Rub Al Khali desert. These mountains carry into Yemen and they are the only location where Boswellia sacra grows naturally, and no other variety of Boswellia grows in them.

The tree itself has little importance in Oman, however, the resin from the tree, when tapped and air-dried, is used daily in most Omani homes. Most commonly the resin is put on a heat source so that smoke is given off. The fragrance from the smoke is fresh with pine and citrus background making its everyday use as an air-freshener most common. Smoking Frankincense resin is also believed to protect from evil, and this is a key element for many people in its daily use within a home and perhaps in a car.

I should not forget to add that the burning of Frankincense is also a key aspect of hospitality in Oman, as an incense burner with smoking Frankincense is presented to guests so that they can use the smoke to fragrance themselves. Very usefully the smoke also drives off flying insects, which is ideal after the rains of the monsoon too!

JBW: Finally, in your own words, what is the best thing about Oman?

TW: Although the historical buildings of Oman are an endlessly interesting part of Oman, for me the best thing about the country is the people, who are welcoming and hospitable to visitors.

JBW: Tony, thank you so much for speaking with me, on behalf of Ancient History Encyclopedia, about your new title and Oman. We wish you many happy adventures in research and in, of course, Oman as well.

TW: It Is my pleasure to speak with you, and I hope you also are able to enjoy Oman in the near future.

Mr. Tony Walsh has written extensively about Oman for local and international media as well as for Oman government publications. He has lived in Arabia since 1986, for most of that time in Muscat. Though initially managing retail businesses in Oman and Saudi Arabia, he has also worked in tourism since 1993, exploring Oman from the Straits of Hormuz to the Yemen border and beyond. His Arabic can justifiably be called "street Arabic" as, although he learnt to read and write in a class, it was the man on the street who taught him the language. His coffee table book on the UNESCO World Heritage Sites in Oman - Walking through History: Oman's World Heritage Sites - covers thirteen locations, which are spread throughout the country, and Walsh has also re-written Bradt's travel guides covering Oman and Muscat. The Land of Frankincense is Walsh's latest publication.