The civil service examinations of Imperial China allowed the state to find the best candidates to staff the vast bureaucracy that governed China from the Han Dynasty onwards (206 BCE - 220 CE). The exams were a means for a young male of any class to enter that bureaucracy and so become a part of the gentry class of scholar-officials. The exams had multiple levels and were extremely difficult to pass, requiring extensive knowledge of Confucian classics, law, government, and oratory amongst other subjects. For the state, the system supplied not only able candidates who were selected on merit but also ensured an entire class developed which had sympathy with the ruling status quo. The exams were in place for over a thousand years and are the principal reason why education is still particularly revered in Chinese culture today.

Historical Development

The idea of recruiting officials to staff the imperial bureaucracy developed from the Han Dynasty. An Imperial Academy had been established in 124 BCE for scholars to study in depth the Confucian and Taoist classics, and by the end of the Han period, this institution was training an impressive 30,000 students each year. In general, the state held the view that education was a mark of a civilised society and in order to get the best administrators to run China's vast territories efficiently, an entire class of scholar civil servants was required. This view would prevail under varying dynasties right up to the mid-20th century CE. From the early 8th century CE the military had its own separate set of examinations.

The rulers of the Sui Dynasty (581-618 CE), who had once again unified China, were keen to further improve and centralise the traditional administration system set up by the Han. There was now a much greater emphasis not on an officials' family connections and their letters of recommendations from powerful friends but on the abilities demonstrated in their performance in civil service examinations held in the capital. These examinations combined elements from tests used in previous regimes such as questions on government and knowledge of the classics of Chinese literature, especially those on Confucianism.

Emperor Gaozu (r. 618-626 CE), founder of the Tang dynasty (618-906 CE) continued with the same policy and added further refinements such as testing a candidate's speaking skills. The examinations themselves were now more sophisticated with both regularly held ones and special event exams to weed out the very best recruits. Now fully established, the civil service examinations tested a young man's knowledge of the following:

- writing and calligraphy

- formal essay writing techniques

- classic literature

- mathematics

- legal matters

- government matters

- poetry

- clear and coherent speaking

Young men also had to present themselves as 'worthy and upright', and for this reason, certain males were excluded, for example, slaves, actors, criminals, and children of prostitutes.

Examinations were initially organised by the Board of Civil Office and thereafter by the Board of Rites, they were held annually, and they attracted up to 2,000 candidates. Extremely testing, only about 1% of examinees actually passed, although it was possible to retake the examinations an unlimited number of times. Those who passed then faced another examination at the Board of Civil Office.

During the Song dynasty (960-1279 CE) the examinations were restructured to meet greater demand - five times that seen during the Tang. Now a qualifying examination was imposed to select those candidates more likely to do well in the examinations proper. These pre-tests were usually carried out in the local provinces and by the end of the dynasty, some 400,000 candidates were sitting them each year. Successful candidates could then participate in the now three-day examination event held annually in the capital. Those who passed that examination were invited to sit another examination in the imperial palace. From 973 CE, the emperor himself personally supervised this last round of exams. There also began in this period certain measures to limit (but certainly not eliminate) corruption such as the introduction of anonymous marking, the use of a number instead of a candidate's name to avoid bias, and, in the case of the second and third level exams, even the copying of handwriting by a clerk to disguise who had answered the papers.

As if the prize ticket of a place in the state apparatus were not enough of an inducement to candidates, there were other benefits, too. Successful candidates were allowed to wear certain robes which became status symbols in wider society, they were given certain tax benefits, and their new status meant they avoided corporal punishment for some criminal offences. As ever, though, candidates had to be male and reasonably well-educated to start off with. Peasant children who could not write or had no access to scholarly texts had no chance of bettering their position in society. Indeed, such were the demands of the exams that parents had to spend a good deal of money on private tutors to get their sons ready for the most important test of their lives. Candidates were helped by the greater availability of printed books, some of which would be compiled specifically to aid exam-takers.

When the Mongols ruled China during the Yuan Dynasty (1276-1368 CE) the exams were first cancelled altogether and then reinstated but with quotas based on a candidate's ethnicity - Han Chinese were only allowed 25% of the exam places. The civil service examination system was fully revived, though, in 1370 CE under the Ming dynasty (1368-1644 CE). Adding their own refinements to the traditional setup of previous Chinese dynasties, the Ming introduced a geographical quota system so that the richer regions did not, as was previously the case, dominate all the positions in the civil service. Meanwhile, the increase in the number of schools meant children with parents who could not afford private tuition could now, at least in some areas, receive the essential education necessary to prepare for the exams.

Ming era exams were held every three years - each autumn in the provinces, then each spring in the major cities for level two, then immediately after, level three in the imperial palace. There were no limits to the number of candidates until numbers grew to such proportions that a measure in 1475 CE limited the candidates to 300 per sitting. There was also some attention given to the degree with which a candidate passed and in which sections. The special 'scholarly' (jinshi) section was given great weight, and it was essential to pass this part to take up senior civil service positions in a candidate's future career. Those who got the best marks in the jinshi section could look forward to a plum job in the prestigious Hanlin Academy, where state documents such as new laws and imperial decrees were compiled, checked, and amended. Despite the rise in candidates, success was still relatively low as examiners kept increasing the challenges. During the Ming, only 2-4% of candidates passed the second level exams and 7-9% the third level.

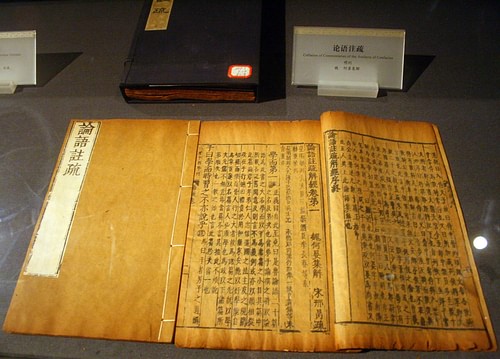

With the spread of Neo-Confucianism, the Ming Dynasty exams also favoured knowledge of the 'Four Books': Analects of Confucius, Mencius, Great Learning, and Doctrine of the Mean. Study of these texts became essential to pass the examinations until their abolition in the 20th century CE. The exams themselves became more exacting with levels one and two each having three separate parts. Candidates had not only to answer questions but also write extended essays, intended to allow examiners to assess the political views of candidates, not just their academic ability. Finally, under the Ming, successful candidates in the lowest level exam who had not passed the second level had to periodically take tests if they wanted to keep their status.

Under the Qing dynasty (1644-1911 CE) yet another layer of complication was added to the exam system. An examination for younger boys, which they had to pass in order to be eligible to take the level one regional civil service exam, was introduced. Although aimed at developing the skills of younger boys, a male of any age had to have passed this exam before proceeding further through the system. The Qing also added another level at the other end of this academic obstacle course. Now candidates who passed the level three palace exam had to do yet another written test, this time set by the emperor himself. The good news was that success in this final paper meant an immediate senior appointment.

A Student's View

The practical implication of such a challenging series of exams was that young boys had to start learning early if they were to have any chance at all of ultimate success. Private tuition from the age of four or five ensured they learnt how to read and write in classic Chinese, which was different from everyday spoken Chinese. Classic Confucian texts had to be memorised if not actually fully understood. Calligraphy skills had to be developed to give a pleasing impression on the first level exams (the other levels had copyists for impartiality as mentioned above). Sound knowledge of China's history was another good foundation to acquire at this stage. Next, they had to acquire the skills of the 'eight-legged' essay, a formalised presentation of ideas with set phrases and structure needed for some of the exam responses.

Closer to the exam, students swatted up on the one classic text they could choose to be tested on in depth (they would be tested on others, too) as well as brushing up their essay writing skills on practical policy issues of the day. For the second and third level exams, a knowledge of imperial edicts, government decrees, and judicial rulings was essential as they would be tested on their ability to draft such official documents.

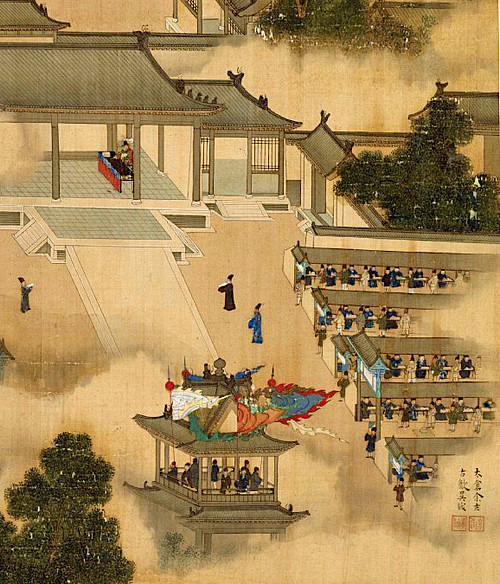

Come exam day in the provinces, all candidates sat in a hall or courtyard of a local government office. The all-day event (repeated twice within a week), was an important one in the community, with stalls being set up to sell food and family and well-wishers gazing on from outside. The second level exams in the cities were spread over a week. Candidates had to present themselves the week before the actual exams with all their paperwork in order (although there was still the odd case of students sending a more able substitute), arrange their accommodation, and make sure they had all the necessary brushes, ink, and paper they would need. Indeed, expected to stay closeted in individual exam cells, they also needed food, candles, and blankets. A cell had an open front so invigilators could check up on everyone. Inside was a number of plain wooden boards to make a desk and seat or a bed. Here, each candidate would spend three days taking the exam. Before entering, each candidate was searched and anyone caught cheating was thrown out, banned from taking the exam the next time it was held, and in some cases, stripped of the certificate they had gained at level one.

The writer Pu Sung-ling (d. 1715 CE) gives the following vivid account of what it was like to sit such an exam:

When he first enters the examination compound and walks along, panting under his heavy load of luggage, he is just like a beggar. Next, while under-going the personal body search and being scolded by the clerks and shouted at by the soldiers, he is just like a prisoner. When he finally enters his cell and, along with the other candidates, stretches his neck to peer out, he is just like the larva of a bee. When the examination is finished at last and he leaves, his mind in a haze and his legs tottering, he is just like a sick bird that has been released from a cage.

(quoted in Dawson, 35)

Once collected, the papers were checked, copied, and presented to the examiners who generally gave out the results within 20 days. Those who passed were invited to a special banquet with the examiners. Those who failed would invariably try again next time. The average age of successful candidates was around 30, with those passing the third level palace exam perhaps being 40 years of age.

Social Impact

The civil service examinations system had several important effects on Chinese society. The very idea that ability was more important than one's family connections and social background was a radical idea that stirred in people of all types the realisation that one did not have to follow the same life and work of one's parents. There were limited places, even more limited jobs at the end of the process, and one needed a basic education to begin with (not to mention one had to be male, too), but there was, at least for some, a possible pathway to social progression.

A side effect of the examination system based on merit was a reduction in the grip on power and wealth held by the hereditary aristocracy. There was, too, a reduction in the potential for corruption by replacing the old system where local officials appointed their own subordinates based on family connections and bribes rather than merit (although high-ranking officials could still circumvent the exam system and nominate people for low positions right through the history of Imperial China). Another side effect of creating this desire to join the scholar-official class was the creation of a compliant section of society who shared common values, one of which was to preserve the system they aspired to join and actively participate in. A fundamental principle of Confucianism was, after all, a sense of duty. Finally, as those taking the exams had to move great distances to do so and, if successful their civil service appointment could be anywhere, at least one section of society became more mobile, continuing the general trend of sections of the population moving from rural to urban communities.

There were several negative consequences to the system, too. Many of those who repeatedly took the exams but failed ended up as frustrated teachers helping other hopefuls or were obliged to find positions as junior clerks, sometimes unpaid. The whole uniformity of the examinations systems encouraged conformity rather than new thinking. In addition, as with any system based exclusively on examinations which hardly ever changed in scope, those who were successful were the ones who best studied how to pass rather than those who best understood the subjects they were questioned on.

The examination system was imitated in other Asian countries, notably in Japan, Korea, and Vietnam. However, as the medieval period wore on and scientific advancements were made elsewhere, particularly in the West, China did lag behind as the exams system emphasised knowledge of classic literature and the cultivation of moral sensibility rather than of scientific and technical subjects. For this reason, after a thousand years and having become part of the very fabric of Chinese public life, the Qing abolished the civil service exams system in 1905 CE. Its legacy remains, though, in the particularly high regard, indeed, almost reverence with which education is held in Chinese culture today.