The camel caravans which crossed the great dunes of the Sahara desert began in antiquity but reached their golden period from the 9th century CE onwards. In their heyday caravans consisted of thousands of camels travelling from North Africa, across the desert to the savannah region in the south and back again, in a hazardous journey that could take several months. Stopping along the way at vital oases, the caravans were largely controlled by the Berbers who acted as middlemen in the exchange of such desired commodities as salt, gold, copper, hides, horses, slaves, and luxury goods. The trans-Saharan trade brought with it ideas in art, architecture, and religion, transforming many aspects of daily life in the towns and cities of a hitherto isolated part of Africa.

The Camel

Although North Africa had once possessed a camelid animal, the Camelus thomazi, this had become extinct during the Stone Age. The dromedary camel (Camelus dromedarius), the one with a single hump, was perhaps introduced from Arabia into Egypt in the 9th century BCE and in the rest of North Africa not before the 5th century BCE (although the precise dates are disputed amongst historians). Camels still did not become common, though, until the 4th century CE. Caravans of horses and donkeys had crossed parts of the Sahara in antiquity but it was the hardy camel which allowed ancient peoples to carry more goods across the inhospitable Sahara and do it faster, reducing both costs and risks. The Encyclopedia of Ancient History has the following summary regarding the advantages of camels as transport:

The value of the camel is not only confined to its high adaptation to severe desert conditions and its regulation of heat and water via its sweat glands: its ability for long-distance travel of about 48 km per day and its high carrying capacity (240 kg) make it a “ship of the desert,” in comparison with the load capacity of horses, donkeys, and mules at roughly 60 kg. Indeed, the camel's life span of 50 years surpasses that of the donkey (30-40 years) and the horse (25-30 years). (1281)

From the 8th century CE, the Moroccans were successfully breeding camels on a huge scale and they even created a cross-breed between the dromedary camel and the two-humped Bactrian camel of Asia (Camelus bactrianus). The result of these experiments produced two variants of dromedaries: a sleek, fast-running camel useful for messenger services and a heavier, slower camel that could carry more weight than the pure dromedary.

The Caravans in Antiquity

Long before the great trans-Saharan caravans of the medieval period, there was a more localised trade between nomadic desert peoples and the tribes of the savannah region south of the Sahara, often called the Sudan region. Rock salt from the Sahara itself, which was badly needed in the salt-impoverished savannah, was exchanged for cereals (e.g. rice, sorghum, and millet), which could not be grown in the desert.

The Greek historian Herodotus, writing in the 5th century BCE (Histories, Bk 4. 181-5), noted a camel caravan route which went from Thebes in Egypt to Niger (although Memphis is more likely to have been the starting point). The Roman writer Pliny the Elder (23-79 CE) noted in his Natural History (5.35-8) that the caravans were managed by the Garamantes, probably ancient Berbers, who lived south of Libya. The Garamantes, in control of the date-palmed oases at Fezzan, acted as middlemen between the peoples of North Africa and sub-Saharan Africa. This arrangement would continue throughout the history of trans-Saharan commerce because those who controlled the desert, who knew the secrets of meeting its formidable challenges, also controlled the trade.

Roman Tripolitania (modern Libya) was supplied with gold, ivory, ebony, cedarwood, and exotic beasts destined for the circuses, while olive oil and luxury goods like fine ceramics, glassware, and cloth were sent south in the exchange. Further east, there were also camel caravans linking Darfur in northwest Sudan to Assiut on the Nile at least from the 1st century CE. Known as the Darb al-Arbein ('Road of 40 Days') it brought ivory and elephants from Africa's interior and thrived into Late Antiquity.

Trans-Saharan Trade Routes

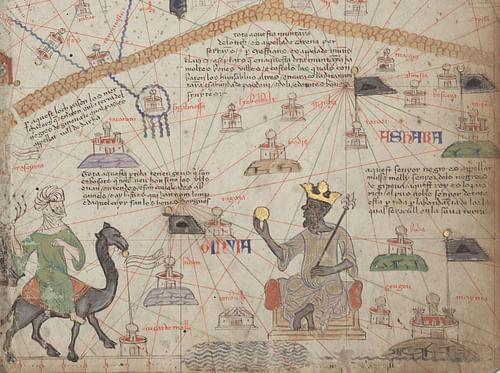

The really large camel caravans that travelled the minimum 1000 kilometres (620 miles) to cross the entire Sahara desert really took off from the 8th century CE with the rise of Islamic North African states and such empires as the Ghana Empire of the Sudan region (6th-13th century CE). Routes would shift over the centuries like the sand dunes of the desert as empires rose and fell either side of the Sahara and as new resources were discovered that could be exploited in the trade that never ceased.

The first route seems to have been between Wadi Draa (southern Morocco) and the Ghana Empire (southern Mali) in the mid-8th century CE and passed through an area of the Sahara controlled by the Sanhaja Berbers. Within 50 years two more major routes had been established which passed through Saharan territory controlled by the Tuareg, an offshoot of the Sanhaja. These were from western Algeria to the Songhai kingdom on the bend of the Niger River and from Libya to Lake Chad (a route blessed by many small oases and a very large one, Kawar). In the mid-11th century CE, a major route went between the Almoravid towns of Sijilmasa north of the Sahara and Awdaghost in the south. In the next century, with the rise of the Almohads in North Africa, Walata would replace Awdaghost at the southern end of the route. Walata was further to the east and so in a better position to act as a collecting point following the discovery of new gold fields. Gao and Timbuktu on the Niger River were also now attracting enough trade to be an end destination for caravans setting off from what is today Tunisia and southern Algeria. The great North African cities of Marrakesh, Fez, Tunis, and Cairo were all important starting or destination points for the trans-Saharan caravans.

From around 1450 CE Portuguese ships were sailing down the Atlantic coast of Africa and offering an alternative to the trans-Saharan caravan routes. From 1471 CE, these ships were accessing the aptly-named Gold Coast in the south of West Africa. However, the rise of the Songhai Empire (1460 - c. 1591 CE) ensured that there was still a huge market and supply of goods for Saharan traders to exploit in the savannah region.

Navigating the Sahara

A typical caravan could have 500 camels but some of the annual ones had up to 12,000 camels in them. These great caravans usually travelled in the best season for travel, winter. To avoid the heat of the midday sun, caravans typically set off at dawn to the call of horns and kettledrums, then rested in the shade of tents during the middle of the day, and moved on again in the late afternoon, continuing until well after dark.

The journey across the Sahara could take at least from 40 to 60 days, and it was only made possible by stopping at oases along the way, but even with these water stops, the journey was brutal and hazardous. That there were established routes, and that Arab medieval writers were so particular in mapping them, is strong evidence that any improvised deviation, the taking of shortcuts or the missing of the next oases through poor navigation or a sandstorm, was very likely to bring disaster. Other dangers included bandits, venomous snakes, scorpions, and the supernatural demons desert people often believed haunted certain parts of the Sahara.

The biggest problem, of course, was water. A person needs a minimum of one litre of water a day in the desert under optimum conditions but this would barely achieve survival. The typical consumption is 4.5 litres a day. Fortunately, camels need not drink anything at all for several days, although when they do reach a water source they drink prodigiously. The chief limit on a caravan, then, was how much water it could carry and how quickly it could get to the next water source along the route.

As well as camel drivers and slaves to do the basic menial tasks, the caravan might have certain officials such as a scribe to record transactions, specialist guides for particular areas of the route, messengers, and an imam to lead daily prayers. Most important of all was the caravan leader, called the khabir, who exercised total authority en route. As with most positions of power, so too came grave responsibilities, and the khabir was liable for any losses and accidents (unless he could demonstrate he was not to blame for them). The historian H. J. Fisher describes the many qualities a good khabir needed:

He knew the desert routes and watering places, and he was able to find his way by the stars at night, or if need be by the scent and touch of the sand and vegetation. He had to understand the proper rules of desert hygiene, remedies against scorpions and snakes, how to heal sickness and mend fractures. He had to know the various chiefs of towns and tribes with which the caravan had to deal along the way, and in this respect a responsible khabir might consolidate his position by strategic marriages in several localities, or into several tribes.

(quoted in Fage, 267)

Besides the stars and the smell of the sand and vegetation, a desert Berber, as today, used many other indicators of direction such as the height of the sun and moon, the lay of the land, mountains on the horizon, the shadows of the dunes, wind direction, the spray of sand blown from the peaks of dunes, ancient eroded gullies, the distribution of rocks and pebbles, the presence of mirages, and the position of camel dung, which is pointed in shape with the point always in the direction of the next water source.

Carrying oneself across the desert, then, was certainly a challenge, guiding camels loaded down with slabs of rock salt was difficult enough, too, but if slaves were being transported, it became a voyage of attrition for everyone, as one 11th-century CE writer noted in his description of the problems of a caravan leader mid-journey:

He was exhausted with his slave men and women. This woman had grown thin, this one was hungry, this one was sick, this one had run away, this one was afflicted by the guinea worm. When they encamped they had much to occupy him.

(quoted in Fage, 639)

Herodotus described caravans stopping every 10 days at a known oasis, the lifelines of the desert. Some of these oases could be mere wells and a few houses but others, like Awdila, the Fezzan group, and the Kufra group (all in Libya), were great spreads of luxuriant greenery, a sight indeed for sore desert traveller's eyes. Here there were date palms, lemon trees, and fig trees, as well as wheat and vines cultivated using irrigation canals. On the other hand, many oases over time simply disappeared under the shifting sands or their waters dried up and they were abandoned to the next sandstorm. Stopping for resupply at an oasis did not come for free either as the tribes that controlled them exacted a tax on the passage of goods through their territory. In order to ensure no outsiders muscled in on the lucrative management of the caravans, Saharan peoples would often cover the smaller desert wells with sand to hide them.

There were attempts to make the journey less inhospitable by increasing nature's meagre offerings along the way. Abd al-Rahman, the governor of Maghrib (r. 747-755 CE), ordered a series of wells to be dug on a route from southern Morocco to the Sudan region. Water was drawn up from such wells using camel-haired ropes and leather buckets, pulled by a camel walking away from the well in a straight line.

Traded Goods

What exactly was worth all the bother of transporting over large distances very much depended on the particular rich elites in the north and south of the desert, something which changed not only because of tastes and fashion but also the rise and fall of states and their access to goods which could be exchanged.

Salt was the major commodity going south which was exchanged for gold, ivory, hides, and slaves (acquired from African tribes conquered by the sub-Saharan empires). Goods were gathered up from across the entire West African region and channelled along the Niger and Senegal Rivers to trading 'ports' like Timbuktu. As the Sudan region saw new and richer empires rise like the Mali Empire (1240-1645 CE) and Songhai Empire, so a wealthy elite sought evermore exotic and expensive goods from North Africa and the wider Mediterranean.

Besides salt, the caravans transported southwards glazed pottery (luxury vases, cups, oil lamps, and incense burners), precious and semi-precious stones (especially garnet and amazonite), cowrie shells and copper wire to be used as currencies, copper ingots, horses, manufactured goods, fine cloth, beads, coral, dates, raisins, and glassware (cups, goblets, and perfume bottles). As the Sudan empires spread their influence and new powers rose such as Hausaland, so this brought in new goods to the trans-Saharan trade like kola nuts (a mild stimulant), ostrich feathers, perfumes, and tobacco.

Legacy

The major and most immediate consequence of the trans-Saharan trade was that it gave states tremendous power in their respective regions as they came to possess goods which were highly valued by their own populations and those of competitor states. These goods could be consumed to enhance the prestige of the ruling class or traded on or taxed which made ruling elites even richer than before and, through the payment of armies, left them in an even more dominant position over subjugated tribes and smaller states. More subtly, there was another kind of baggage besides the trade goods which came with the merchants who crisscrossed the Sahara. Ideas, technology, and religion all spread, too.

Although the extent of either direction's cultural influence is difficult to gauge precisely, we do know that Islam was introduced into the Sudan region via northern traders from the 9th century CE. Mosques and Islamic town planning began to be seen in Sudan towns. The adoption of precise scales using accurate glass weights was adopted in some Sudan cultures, almost certainly in response to the need to accurately measure gold dust. However, some things did not seem to catch on. For example, the import of Mediterranean pottery had little effect on the production of traditional Sudan pottery shapes and designs. So, too, better kilns capable of higher firing temperatures have been revealed by archaeology in the north but were not adopted in the Sudan. In the other direction, the technique of mud-rubble to fill wall cavities may have been adopted in the north from Sudan practices.

The caravans, albeit on a much smaller scale than in their heyday, are still going today. Saharan salt from Taoudenni is still transported by Tuareg camel caravans, the 90-kilo slabs now ultimately destined for the refineries of Bamako in Mali. Four-wheel drive vehicles and satellite phones may be of enormous value to modern desert travellers but the camel still remains one of the most dependable ways to reach and transport goods in the remoter parts of the Sahara.