Women in the Middle Ages were frequently characterized as second-class citizens by the Church and the patriarchal aristocracy. Women's status was somewhat elevated in the High and Late Middle Ages by the cult of the Virgin Mary and courtly love poetry but, even so, women were still considered inferior to men owing to biblical narratives and the patriarchy.

Still, there were many notable women throughout the Middle Ages who were able to break from societal norms to live the kind of life they chose for themselves and claim a position of power traditionally associated with males. In almost every case, these women were from the upper class and had slightly more social mobility than the lower classes, but there are records clearly indicating that women throughout the Middle Ages worked alongside men in medieval guilds and were significant and sought-after artists, writers, illustrators, artisans, and monarchs.

Famous Women of the Middle Ages

Scholars divide the Middle Ages into three periods:

- Early Middle Ages – 476-1000

- High Middle Ages – 1000-1300

- Late Middle Ages – 1300-1500

There were many famous women throughout these three eras but the following twelve are among the best-known:

- Empress Theodora of Byzantium

- Hilda of Whitby

- Ende the Illuminator

- Aethelflaed, Lady of the Mercians

- Matilda of Tuscany

- Hildegard of Bingen

- Eleanor of Aquitaine

- Marie de France

- Julian of Norwich

- Christine de Pizan

- Margery Kempe

- Joan of Arc

Many of these women significantly influenced their own time as well as later generations through their vision and ability to act on that vision. How women were perceived by society through the lens of the Church, how they were considered as legal and social entities by the law, and how they actually lived out their lives were never precisely the same, but the women named above took control of their situations to live as independent women, equal to men, in a patriarchal society. Scholar Eileen Power comments:

The position of women is often considered as a test by which the civilization of a country or age may be judged. The test is extraordinarily difficult to apply, more particularly to the Middle Ages, because of the difficulty of determining what in any age constitutes the position of women. The position of women is one thing in theory, another in legal position, yet another in everyday life. In the Middle Ages, as now, the various manifestations of women's position reacted on one another but did not exactly coincide; the true position of women was a blend of all the three. (9)

The Church exerted the greatest influence over how women were perceived through the teachings of the Bible. Famous biblical heroines such as Ruth or Deborah, the Virgin Mary or Mary Magdalene were countered by Eve or Jezebel and the admonitions of St. Paul in his epistles which claimed that men were superior to women and women should submit themselves to male authority. Even though more women were able to assert themselves in the latter part of the Middle Ages, some did so even earlier.

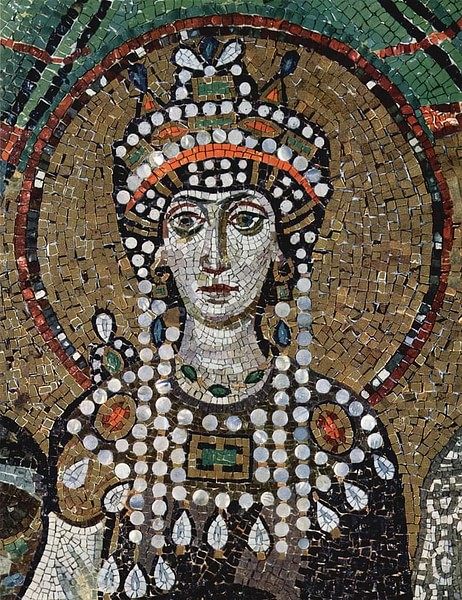

Theodora of Byzantium

Theodora (l. 500-548) was an actress in Constantinople (and possibly a prostitute) who converted to Christianity and took up wool-spinning and weaving as a profession. How she met the future emperor Justinian (r. 527-565) is unclear, but he was so in love with her that he changed the law which forbade royalty from marrying actresses and made her his wife and partner in rule.

Theodora was an empress regnant, a female monarch with power equal to the emperor, and Justinian regularly took her counsel to heart. The most famous example of this is when she talked Justinian and his court out of fleeing the city during the Nika Riots of 532. She is said to have cleverly conceded to the court that she was aware a woman should not speak in the presence of men but that the situation at hand called for extreme measures. She then advised them against fleeing the city simply to preserve their own lives because such lives afterwards would not be worth living. Justinian accepted her advice and dealt with the problem instead of running from it. The couple ruled the Byzantine Empire jointly until Theodora's death, possibly from breast cancer, in 548.

Hilda of Whitby

Hilda (l. 614-680) was a noblewoman in the early days of the Kingdom of Northumbria who chose a life of piety and devotion to one at court. She rose from a novice to abbess of her order and founded Whitby Abbey, which became a center for learning and culture. Hilda was an able administrator who took care of the many facets of running the sizeable estate of the abbey but was always available for counsel and encouragement. She is known as the patron saint of poets for inspiring the shepherd Caedmon to write his famous hymn, the oldest extant poem in Old English. In 664, King Oswiu of Northumbria chose Hilda's abbey as the site for the synod which decided to accept Roman Catholicism over Celtic Christianity as the official religion of the region, and he did so because of Hilda's reputation for wisdom and the strength of her counsel. She became even more famous after her death when a number of miracles were attributed to her and she was venerated as a saint.

Ende the Illuminator

It is well-established that, by the 13th century, women were involved in book production as scribes, illustrators, and illuminators of manuscripts, but Ende's work makes clear that women were involved in this process as early as the 10th century. Ende was a nun at a monastery in Spain when she worked on the manuscript now known as the Gerona Beatus compiled by the monk Beatus of Liebana in c. 786. The manuscript, now housed at the Gerona Cathedral in Catalonia, Spain, is signed by the artists who worked on it and includes the line "Ende pintrix et Dei adiutrix" (Ende, painter and God's helper); the feminine form of the Latin makes clear that the illuminator was a woman. Other female illuminators and scribes are known from later centuries, including Guda (12th century) and Claricia (13th century), but Ende is the earliest known to date.

Aethelflaed, Lady of the Mercians

Aethelflaed (r. 911-918) was the daughter of Alfred the Great (r. 871-899) and became Queen of Mercia following the death of her husband Aethelred II. As a daughter of Alfred, who believed literacy encouraged piety, she was highly educated and cultured. Her court was a well-known center of culture at which her nephew Athelstan, future King of the Anglo-Saxons and first King of England, grew up under her patronage.

She is best known as the Lady of the Mercians who defeated the Vikings at the Battle of Chester in 907 by carefully planning the defense of the city as an offensive ambush. She formed alliances with Irish mercenaries to aid in defense of her kingdom, planned and organized the cities and villages for maximum efficiency and aesthetic charm, and worked with her brother Edward the Elder of Wessex to protect the region against further Viking raids and to boost the economy. At her death, she was briefly succeeded by her daughter Aelfwynn before her kingdom was absorbed by Edward into Wessex.

Matilda of Tuscany

Matilda (1046-1115, also known as Matilda of Canossa) was one of the most powerful women in the Middle Ages and the preeminent political force in medieval Italy. She is best known for her military prowess in defending her lands and the authority of Pope Gregory VII (c. 1073-1085) from the aggression of Henry IV of the Holy Roman Empire (r. 1056-1105). Matilda personally supervised military operations and expeditions while ably managing the affairs of state which included administration over a vast kingdom. Following the death of Gregory VII, Matilda continued to defend the papacy and her reign until finally defeating Henry IV in battle personally in 1095. In 1111, she was crowned Imperial Vicar and Vice-Queen of Italy by Henry V.

Hildegard of Bingen

Hildegard (1098-1179) was a German polymath; a mystic, healer, scientist, visionary, author, composer, and abbess who claimed to receive visions from God from the time she was three years old and never doubted their truth. In 1150, she is said to have received a vision to move her order to Rupertsburg and, when her male superior refused her, she pressed the issue until her request was granted. A female cleric standing up to a male superior in an order never ended well for the woman and yet Hildegard prevailed and even founded a second order on her own after establishing herself at Rupertsburg. She never received a formal education but was highly literate as well as being well-versed in musical composition. She corresponded with others regularly and left behind a large collection of letters in addition to her literary, religious, scientific, medical, and musical works.

Eleanor of Aquitaine

Eleanor (l. c. 1122-1204) was Queen of France, Queen of England, wife of two kings, mother of King Richard I (the 'Lion-heart'), King John of Magna Carta fame, Marie de Champagne (patroness of Chretien de Troyes), as well as a number of other notable children. She personally participated in the Second Crusade along with her ladies-in-waiting, allegedly riding bare-breasted into battle at one point to distract the Saracens.

Her accomplishments were numerous, but among them was her role as patroness of the arts which encouraged the development of the concepts of courtly love and chivalry in French literature. Although the impact of these concepts on medieval society is still debated, there is evidence that the works of authors like Chretien de Troyes and Andreas Cappelanus significantly influenced the aristocracy to regard women more as individuals and less like property.

Marie de France

Marie (wrote c. 1160-1215) was a multilingual French poet, translator, and proto-feminist best known for her poetic work The Lais of Marie de France which popularized the concept of courtly love, the chivalric code, and the power of women. She is recognized as the first female poet of France but seems to have spent the majority of her time in Britain and was closely associated with the court of Henry II and his wife Eleanor of Aquitaine. She is usually credited with establishing the medieval genre of chivalric literature but this is challenged on the grounds that Andreas Cappelanus and Chretien de Troyes – two notable pioneers of the genre - were writing at the same time and, probably, for the same patroness (Eleanor) and her daughter Marie de Champagne. Marie de France's poetry and fables were very popular among the aristocracy of France and England even though they directly challenged the position of the Church on women as the weaker sex, subordinate to male authority. Marie's poetry frequently features strong women who dominate men and are able to direct their own fates, even if they eventually are destroyed by their resistance to the patriarchy.

Julian of Norwich

Julian (l. 1342-1416, sometimes given as Lady Juliana of Norwich) was a mystic, visionary, and author of the masterpiece of religious literature, Revelations of Divine Love. Julian's actual name is unknown, and her pen name comes from her residence at St. Julian's Church in Norwich, England. In May 1373, Julian believed she was dying and, as she lay in her bed, received a number of visions from God which she wrote down shortly afterwards. She expanded on her original manuscript years later, developing her earlier thoughts to greater extent. Her essential message focused on God's compassion and love for all, and she empowered women by comparing God's love to a mother's love which accepts all her children's failings without judging. The anger and condemnation so often seen in the official position of the Church, she claimed, came not from God but from men because God had only the best in mind for humanity and, as she wrote, “all will be well and every manner of thing will be well” in spite of how circumstances might appear. Her work was relatively unknown until the early 20th century when it inspired and influenced poets such as T. S. Eliot, but in her own time she was well-known for her counsel and her influence on the medieval mystic Margery Kempe.

Christine de Pizan

Christine (l. 1364-1430) was the first professional female writer in Europe, counselor to kings and aristocracy, and proto-feminist whose works were highly influential in her own time and continued to be in later centuries. Christine was married to an aristocratic court secretary who died of the plague in 1389. With no means to support herself, her children, and her elderly mother, Christine turned to writing. Her father had encouraged her literary pursuits and so, even though she was never formally educated, she could read and write and never seems to have regarded her lack of professional training a bar to success.

She is best known for The Book of the City of Ladies and The Book of the Three Virtues, also known as The Treasure of the City of Ladies, both published in 1405. The first is her refutation of misogynist characterizations by the medieval author Jean de Meun in his popular Romance of the Rose, and the second is a hands-on practical advice manual for women in caring for themselves, their finances, husbands, and estates. Her works were quite popular in her lifetime and she was frequently sought for advice.

Margery Kempe

Margery (l. c. 1373 - c. 1438) was a Christian mystic who dictated her experiences and visions to create the first autobiography in English, The Book of Margery Kempe. In her life and work, she consistently challenged the patriarchy of the Church and was tried a number of times for heresy but never convicted. Her devotion to God and belief in the truth of the visions she received made it impossible for her to keep quiet about her faith and she frequently bore witness publicly in the communities where she lived. The prohibition against female clergy and biblical admonition against women teaching men or speaking in a man's presence led to further conflict with the clergy as well as laymen of the towns she lived in. She visited Julian of Norwich in c. 1413 for validation of her visions and mystical experiences, which Julian granted. Margery was either illiterate or poorly educated and dictated her book, in part, to reach a wider audience than she could in person.

Joan of Arc

Joan (l.1412-1431, also known as Jeanne d'Arc) was a French visionary mystic and military leader known for her victories in the Hundred Year's War and tragic death by execution in 1431. She claimed to have received a message from God in a vision of three saints who appeared to her when she was 13 directing her to drive the English from France and ensure the coronation of the Dauphin at Rheims.

Joan, a poor farm girl with no military experience, persevered through repeated obstacles and snubs from French military officials until she was granted access to arms and armor and allowed to join the army. She lifted the siege of Orleans, leading men in battle, and participated in strategic and tactical engagements afterwards but was captured by the Burgundian allies of the English and handed over to an English tribunal who executed her for heresy in 1431 through burning at the stake. Joan was 19 years old at the time of her death. The sentence of the court was later invalidated and Joan is honored as one of the patron saints of France in the present day.

Conclusion

There were, of course, many other women of note throughout the Middle Ages. Some of these are the German dramatist and poet Hrotsvitha (10th century); the Scottish queen Gruoch (11th century), model for Shakespeare's Lady Macbeth; the Italian physician Trota of Salerno (c. 1100); Jeanne de Clisson (c. 1300-1359), the Breton pirate, and the Italian feminist/humanist author Laura Cereta (1469-1499).

Many other women's names are known from court documents, business transactions, land sales, and successfully running their late husband's business, their own business, as well as managing estates and as valued members of medieval guilds. Lady Eleanor of Montfort (also known as Eleanor of England, l. 1215-1275) negotiated the surrender of Dover Castle so successfully that her supporters were pardoned and Brunhilda of Austrasia (l. c. 543-613) ruled the Frankish kingdoms of Austrasia and Burgundy.

There were, no doubt, many other women who also lived notable lives but whose names are now lost because they went unnoticed by the male writers of their time. The names of the most famous women of the Middle Ages are still known in the present day not because the patriarchy of the time valued them, for the most part, but in spite of that social hierarchy which denied women the avenues of expression and autonomy open to men.