Today, Marseille is known more for its modern history – World War II, North African immigration, and, of course, the rousing choruses of France's national anthem, La Marseillaise. Yet it is also one of France's most ancient cities, one rich in traces of the pre-modern past – for those who go looking.

There are plenty of ways to pass time in the city, from exploring the 17th-century CE Fort St-Jean to spending hours in the spectacular Museum of European and Mediterranean Civilizations (MUCEM). Locals like to lay out in the sun, here, and swim in the sparkling-blue harbor. But here I am, on a bright and lovely day, hunting for traces of early Christian cults.

Marseille was one of the first places that early Christianity landed in the West. The city has a long history as a trading port, bustling with merchants and cosmopolitan ideas. It was founded by Greek colonists from Phocaea, now in southern Turkey, in 600 BCE. Massilia, as it was then known, quickly became a center of Hellenistic (Greek) civilization in the western Mediterranean. It picked the wrong side during the Roman Civil War of 49 BCE, and it was the armies of Julius Caesar himself who officially brought the city into the Roman Empire. It was after the Roman conquest that nascent Christianity, like perfumes and spices and silks, arrived from the East into the port of Marseille and spread to the rest of Gaul.

A misty layer of legend surrounds the exact date of Christianity's arrival – and the question of who, exactly, brought it. Many of these theories date back to the early Middle Ages. Some say that it was Lazarus, the man Jesus raised from the dead, who – banished from Palestine – arrived in Marseille and became the city's first bishop. Others claim that it was Mary Magdalene, landing on the rocky shores of what is now the Camargue National Park and spending the rest of her life in the nearby mountains. An hour outside the city is the Grotto of Saint-Baume, said to be where she ended her days.

These stories are doubted, of course, and cannot be confirmed. Still, they speak of a sense the locals have about the deep roots of Christianity in Marseille, and in Provence more generally.

There was certainly a Christian community in Arles (then called Arelate) in 254 CE, and Marseille had an official congregation by 314 CE, the year after Emperor Constantine (r. 306-337 CE) converted to Christianity. Some of France's oldest Christian buildings are in the region.

Compared to some of Provence's ancient villages, Marseille is a less obvious place to go looking for marks of the distant past. This is a thoroughly modern city, one whose tumultuous history has impressed upon it the distinctly 19th-century style, with Parisian apartment buildings decorated with wrought iron balconies. Those traces, however, are absolutely here. They offer us a way to understand the regional importance of early Christianity and to explore two of its most important aspects: saints and monasticism.

Marseille Cathedral

Walking along the waterfront in Marseille, it is hard to miss the Cathedral, which is colloquially known as “la Major.” Standing right near the Old Port, it is a massive construction, entirely striped in black and white. The church was built in the 19th century CE, but its design was intended to evoke Byzantine and Roman splendor.

Romanesque architecture generally gets associated with darkness and gloominess, but on a hot and sun-soaked day, one instantly understands the appeal. Walk inside la Major and the heat, dust and hubbub of Marseille's busy port suddenly disappear, replaced with an atmosphere of serenity. This might only count as relative serenity in peak tourist season, but it still hints at reasons for the endurance of the small-windowed Romanesque style in this region. Huge Gothic windows turn churches into greenhouses – good for a gloomy North English village, but less desirable in a climate with sunshine to spare.

The church has many attractions, including the beautiful patterning along the façade's primary arch. But I have come to bear witness to one particular sight. Walk down the right side of the church. At the back of the large chapel stands a golden statue: it wears a bishop's hat and carries a crook. At its feet, there is a box made of gold and glass. Here - in the box - is Saint Lazarus.

Why were relics so important to early Christianity? To some extent, it is an open question: relics run precisely contrary to Judaism's prevailing ideas about ritual purity. The Greeks worshipped heroes in a way that can be seen as a precursor to the veneration of saints, establishing temples around their tombs, and Egyptian ideas about the dead had been infiltrating the Mediterranean world for a long time. Perhaps, too, the importance of relics can be linked to the importance of martyrdom.

Martyrs, for a long time, were a Christian ideal. All early Christians declared themselves ready to die for their faith, sometimes even going so far as to goad Roman imperial authorities into indulging them. Death and its veneration lay at the heart of what it meant to be Christian. According to standard Roman practice, when martyrs were executed, their bodies would often be destroyed. Fellow believers would gather up the remnants that escaped destruction. Even after Constantine converted and Christianity became the religion of the state, martyrdom was still a religious ideal.

The relics of martyrs and saints retained the saint's divine powers. They healed the sick, especially. They were also powerful expressions of folk religion. Sainthood was completely unregulated by the central church until later in the Middle Ages, so saints were popularly elected by the people in the milieu of a particularly holy man or woman. Their remains would be gathered up, hosted in elaborate reliquaries and placed in churches named for them; festivals were celebrated in their honor.

Is the skull behind the glass windows – in a reliquary whose golden arches evoke those of the cathedral itself – really Lazarus'? It might not be: the Orthodox Church holds competing relics that are also claimed to be those of the Lazarus raised by Jesus. The skull in Marseille could belong to a different Lazarus, a bishop from nearby Aix-en-Provence, who was buried in the Abbey of Saint Victor in 420 CE. The body of the other Lazarus was supposedly hidden in the Abbey of Saint Victor to protect them from Saracen pirates – so one can imagine how the mix-up might have happened. It might not matter either way. Relics have always been symbols of divine blessing more than literal historical artifacts.

The story of the relics, and their controversy - they were recognized and then unrecognized in turn by the church - is told on nearby informational banners, all in French. It feels like a shame to leave them behind, but there is more exploring to do.

Church of St. Laurent

It is a straight line uphill from La Major to the entrance of the Fort St-Jean. Across the street stands the rather unassuming Church of Saint Laurent, built in the Romanesque style in the 12th century CE. After the splendor of Marseille Cathedral, there is something comforting about the simplicity of this church.

The Church of St. Laurent itself was built in the throes of the Middle Ages, much later than the early-Christian period of my interest. Yet the architecture of the church is quite similar to what those early churches may have looked like. It offers a sense of what day-to-day religious life might have felt like, with its simple decoration which focuses on liturgy rather than adornment. Early Christians thought that images, especially of holy figures, were a slippery slope to idol-worship; they rampaged through Roman temples destroying sculptures. It is not until much later that the elaborate adornment of churches came into being.

Despite its proximity to the Fort, this church does not receive many visitors. It is a fit place to relax, and to appreciate the calm.

Abbey of St. Victor

My last stop is right next to the Old Port and in the shadow of Fort Saint-Nicolas. With its towers, it looks more like a stereotypical medieval castle than a monastery. But this is the Abbey of Saint Victor, one of the first monasteries established in the Christian West.

The abbey was built in honor of a martyr. Saint Victor, a Roman soldier, was killed in 303 CE for refusing to sacrifice to the Roman gods because of his Christian faith. His relics were hidden by supporters in a nearby rock quarry, which quickly became a place for pilgrimage and one of the holiest places in Massilia. In the 5th century CE, Saint John Cassian (360 - 435 CE), arriving from the East, founded a chapel on the site. Born in Romania, Cassian had been a monk in Bethlehem and had traveled all over Palestine and Egypt, where the first monastic movements were forming. Men like Saint Anthony of the Desert (251 - 356 CE) were withdrawing from human society, finding holiness in solitude, prayer and asceticism, the practice of self-denial.

Saint Cassian was not the person who brought Eastern-style monasticism to Provence - it had arrived via North Africa sometime before. But the Abbey of St. Victor and two books that he wrote around the same time helped to popularize the life for the men and women of Roman Gaul. For him, living in a spirit of brotherhood was a central part of monastic life - monks should live and pray together, not banish themselves to silence.

Monks and their abbeys were extremely influential in the formation of Christianity as we know it: famously, too, they were the main transmitters of religious and secular knowledge through most of the Middle Ages. The Abbey of St. Victor never achieved the prominence of other southern French abbeys such as Cluny, but it was a center of religious life for Marseille. It also preserves some remarkable vestiges of its earliest origins.

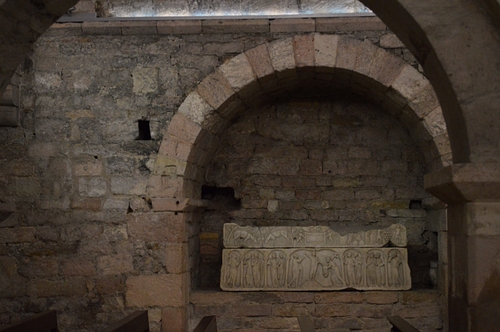

The church as it stands today was built around the year 1000 CE when the abbey was given over to a Benedictine order, so I headed right down to the crypt. The walls were built along with the rest of the church, but there are elements of the older church that remain. It was in underground spaces like these that early Christians celebrated mass: close to the tombs of the martyrs, far from the prying eyes of those that disapproved of the new religion. There is still a secretive atmosphere to the crypt, although the high ceilings keep it from feeling claustrophobic.

It is easy to lose track of time here, going from one elaborately carved sarcophagus to the next. These figures, carved out of local limestone, are a perfect mix of classical Roman sculpture and the medieval ones familiar from later churches. A small children's coffin shows the wolf that suckled Romulus and Remus. I peek into every corner and spend some time in front of the mosaic in the oldest part. It is hard not to imagine those early monks putting the shards together, combining an ancient artistic practice with their radical new religion.

When I visited St. Victor's, the alcoves were being used for an exhibition of contemporary work by a Spanish artist, and the space was full of the sound of a choir practicing Gregorian chants. Almost 2,000 years of religious practice were suddenly all together.

***

If Marseille has piqued your interest, then Provence hosts thousands of other early Christian treasures between lavender fields and vineyards - and, of course, ancient sites. To the east, near Cannes, lies the Merovingian (5th century CE) splendor of Fréjus Cathedral. Around an hour away is Arles, best known for its spectacularly preserved Roman ruins but also home to the eerily beautiful Church of St. Trophime. In addition to having a spectacular collection of early relics - among them being the head of St. Anthony - St. Trophime has undergone a series of architectural updates over the centuries. From a tiny chapel, it has been added to in a way that leaves every layer of history. There is no better way to appreciate Christianity's twists and turns.