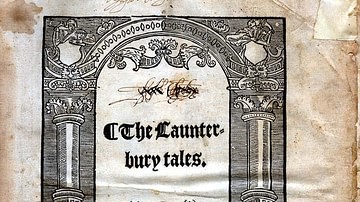

The Book of the Duchess is the first major work of the English poet Geoffrey Chaucer (l. c. 1343-1400 CE), best known for his masterpiece The Canterbury Tales, composed in the last twelve years of his life and left unfinished at his death. The Canterbury Tales, first published c. 1476 CE by William Caxton, became so popular that Chaucer's earlier work was overshadowed, only receiving critical attention much later and popular notice as late as the 19th century CE.

Among these is The Book of the Duchess, composed c. 1370 CE in honor of Blanche, Duchess of Lancaster (l. 1342-1368 CE), wife of John of Gaunt (l. 1340-1399 CE), Duke of Lancaster and Chaucer's best friend. Blanche died in 1368 CE, probably from the plague, at the age of 26, and John of Gaunt mourned her for the rest of his life even though he would remarry. The Book of the Duchess is thought to have been composed on the second anniversary of her death. It may have been commissioned by John of Gaunt and was read at Blanche's memorial service on the two-year anniversary of her death. The poem was clearly appreciated by John of Gaunt as, afterwards, he rewarded Chaucer with a grant of ten pounds a year for life, at that time equal to almost a year's salary.

The poem is written in Middle English and belongs to the literary genre known as the high medieval dream vision in which a narrator opens by relating some problem he is experiencing and then falls asleep, has a dream which suggests or clearly reveals a solution to the problem, and wakes feeling at peace or resigned to his situation. Chaucer's piece deviates from this form in that the narrator never claims to have resolved his problem through the dream; the poem ends simply with him saying he woke and wrote the dream down.

This being so, the entire poem should be understood as having been written after the narrator woke from the dream and so his problem of unrequited love – which he describes as a "sickness" he has suffered from for eight years (lines 36-37) – continues even after the dream. Chaucer would have crafted the piece in this way to highlight the difficulty in moving on from loss. The poem offers no solution to the problem of grief other than a compassionate listener in the form of his narrator. Through a series of questions and by relating stories, the narrator helps the knight relive the joys of his relationship and express his grief over the loss of his wife even though there is nothing he can do to relieve it.

Summary

The poem opens with the narrator complaining that he cannot sleep and lives in a kind of apathy where he feels neither joy nor sorrow, does not care about anything, and fears he may die because of his lack of sleep (lines 1-29). In lines 30-42 he says how he does not really know why he is experiencing this but can guess and how there is only one physician who can heal him but will not do so. The poem relies on an audience's acquaintance with the romantic vision of courtly love, a poetic genre of medieval literature developed in Southern France in the 12th century CE which frequently featured a knight hopelessly in love and devoted to a lady. The lady in these poems is often depicted as a physician who can heal the knight either emotionally, spiritually, or physically, and so the 'physician' the narrator refers to in line 39 is a lady he loves who has either left him or will not return his love.

Since he cannot sleep, the narrator reads a book (Ovid's Metamorphosis, though the title is never given) containing the story of the lovers Seys (usually given as Ceyx) and Alcyone. Seys goes on a sea voyage and, when he fails to return on the given day, Alcyone begins to worry. She prays to the goddess Juno for a sign of whether Seys still lives and her prayer is answered in the form of Morpheus, god of sleep, appearing as Seys to tell her he is dead. Alcyone dies of grief three days later (lines 62-214). The narrator then marvels at the story and how Alcyone received an answer to her prayer when he has not and so he prays to Juno, almost instantly falls asleep, and begins to dream (lines 215-291).

He finds himself in bed on a May morning with birds singing and quickly gets dressed to join a hunt in progress outside. He is separated from the others in the party and walks alone through the woods until he comes upon a man in black sitting alone (lines 292-445). The man, described as a handsome and noble knight, is writing a poem and completely unaware of the narrator. The poem is a lament for lost love, which the knight recites as he writes, in which he says how the love of his life has died and he will never feel joy again. The narrator is moved by the poem and even more so by the knight's obvious sorrow and moves to comfort him, but the knight is so deep in despair he does not notice at first (lines 445-514).

The narrator apologizes for disturbing the knight, says how he is obviously depressed and asks what he can do to help. The knight answers that there is nothing anyone can do and then relates how miserable his life has become, how he curses fortune which has stripped him of happiness, and how life is meaningless now whereas once it was bright and joyful (lines 515-709). The narrator then tries to console him by reminding him of the wisdom of Socrates in confronting fate, and how famous lovers have suffered throughout history like Medea with Jason, Dido with Aeneas, Samson with Delilah (lines 710-740).

The knight tells him he does not know what he is talking about because the knight has lost far more than any of the people cited and tells him to sit down and he will make the problem clearer. The knight then tells the narrator of how he met this beautiful woman, fell in love, and married her (lines 741-1041). The narrator interrupts to say how his wife sounds very nice but she could not have been as perfect as the knight is depicting her. The knight replies how everyone saw her in the same way and there was never anyone as beautiful or kind or gentle as she (lines 1042-1111). The narrator still does not grasp the knight's problem and asks him to tell of their first words with each other and how she came to know he loved her and then asks plainly what has gone wrong with the relationship (lines 1112-1144).

The knight obliges and tells the narrator of the first song he composed for her and then talks about their relationship and how much she meant to him (lines 1145-1297). The narrator asks, "Where is she now?" and the knight replies, "She is dead" at which the narrator exclaims, "Be God, hyt is routhe!" (literally, "it is sorrowful" but better translated as "I am so sorry!") and instantly hears the hunting party returning. He then wakes from the dream to find himself in his bed with the book of Seys and Alcyone in front of him, marvels at the dream he had and says how he knew he had to write it down immediately (lines 1298-1334). The poem ends with the narrator saying how he has done so and now his dream his done.

The Text

The Book of the Duchess, like all of Chaucer's works, is written in Middle English, well before spelling was standardized by the poet, writer, and lexicographer Samuel Johnson (1709-1784 CE) wrote the first English dictionary. Words are spelled as they sound and the poem is written to be read aloud. Read silently, the meaning of a word is not always clear but, out loud, and within the context of the sentence, is better understood. The first line, for example, “I have gret wonder, be this lyght” is clearly “I have great wonder, by this light” when spoken out loud.

The letter 'Y' stands for 'I' but stresses on syllables follow the rhyme of the poem and so the 'Y' is sometimes sounded as 'ee' and sometimes as 'ee-uh'. The word 'quod' or 'quoth' means 'to speak' and a 'sweven' is a 'dream'. Other words, which may at first seem strange, are intelligible within the sentence's context where the spelling of a previous word, closer to modern English, will make the meaning clear. The following text comes from the online site Libarius.com (cited in the bibliography below) which provides hyperlinks and glossary to Middle English on its site. This is the standard version as found in The Riverside Chaucer edited by scholar Larry D. Benson, 1987 CE.

I have gret wonder, be this lyght,How that I live, for day ne nyght

I may nat slepe wel nigh noght,

I have so many an ydel thoght

Purely for defaute of slepe 5

That, by my trouthe, I take no kepe

Of nothing, how hit cometh or gooth,

Ne me nis nothing leef nor looth.

Al is ylyche good to me —

Joye or sorwe, wherso hyt be — 10

For I have felyng in nothyng,

But, as it were, a mased thyng,

Alway in point to falle a-doun;

For sorwful imaginacioun

Is alway hoolly in my minde. 15

And wel ye woot, agaynes kynde

Hit were to liven in this wyse;

For nature wolde nat suffyse

To noon erthely creature

Not longe tyme to endure 20

Withoute slepe, and been in sorwe;

And I ne may, ne night ne morwe,

Slepe; and thus melancolye

And dreed I have for to dye,

Defaute of slepe and hevynesse 25

Hath sleyn my spirit of quiknesse,

That I have lost al lustihede.

Suche fantasies ben in myn hede

So I not what is best to do.

But men myght axe me, why soo 30

I may not slepe, and what me is?

But natheles, who aske this

Leseth his asking trewely.

Myselven can not telle why

The sooth; but trewely, as I gesse, 35

I holde hit be a siknesse

That I have suffred this eight yere,

And yet my boote is never the nere;

For ther is phisicien but oon,

That may me hele; but that is doon. 40

Passe we over until eft;

That wil not be, moot nede be left;

Our first matere is good to kepe.

So whan I saw I might not slepe,

Til now late, this other night, 45

Upon my bedde I sat upright

And bad oon reche me a book,

A romaunce, and he hit me took

To rede and dryve the night away;

For me thoghte it better play 50

Then playen either at ches or tables.

And in this boke were writen fables

That clerkes hadde, in olde tyme,

And other poets, put in ryme

To rede, and for to be in minde 55

Whyl men loved the lawe of kinde.

This book ne spak but of such thinges,

Of quenes lyves, and of kinges,

And many othere thinges smale.

Amonge al this I fond a tale 60

That me thoughte a wonder thing.

This was the tale: There was a king

That highte Seys, and hadde a wyf,

The beste that mighte bere lyf;

And this quene highte Alcyone. 65

So hit befel, therafter sone,

This king wolde wenden over see.

To tellen shortly, whan that he

Was in the see, thus in this wyse,

Soche a tempest gan to ryse 70

That brak hir mast, and made it falle,

And clefte her ship, and dreynte hem alle,

That never was founden, as it telles,

Bord ne man, ne nothing elles.

Right thus this king Seys loste his lyf. 75

Now for to speken of his wyf: —

This lady, that was left at home,

Hath wonder, that the king ne come

Hoom, for hit was a longe terme.

Anon her herte gan to erme; 80

And for that hir thoughte evermo

Hit was not wel he dwelte so,

She longed so after the king

That certes, hit were a pitous thing

To telle hir hertely sorwful lyf 85

That hadde, alas! this noble wyf;

For him she loved alderbest.

Anon she sente bothe eest and west

To seke him, but they founde nought.

'Alas!' quod she, 'that I was wrought! 90

And wher my lord, my love, be deed?

Certes, I nil never ete breed,

I make a-vowe to my god here,

But I mowe of my lord here!'

Such sorwe this lady to her took 95

That trewely I, which made this book,

Had swich pite and swich routhe

To rede hir sorwe, that, by my trouthe,

I ferde the worse al the morwe

After, to thenken on her sorwe. 100

So whan she koude here no word

That no man mighte fynde hir lord,

Ful ofte she swouned, and saide 'Alas!'

For sorwe ful nigh wood she was,

Ne she koude no reed but oon; 105

But doun on knees she sat anoon,

And weep, that pite was to here.

'A! mercy! Swete lady dere!'

Quod she to Juno, hir goddesse;

'Help me out of this distresse, 110

And yeve me grace my lord to see

Sone, or wite wher-so he be,

Or how he fareth, or in what wyse,

And I shal make you sacrifyse,

And hoolly youres become I shal 115

With good wil, body, herte, and al;

And but thou wilt this, lady swete,

Send me grace to slepe, and mete

In my slepe som certeyn sweven,

Wher-through that I may knowen even 120

Whether my lord be quik or deed.'

With that word she heng doun the heed,

And fil a-swown as cold as ston;

Hir women caught her up anon,

And broghten hir in bed al naked, 125

And she, forweped and forwaked,

Was wery, and thus the dede sleep

Fil on hir, or she toke keep,

Through Juno, that had herd hir bone,

That made hir to slepe sone; 130

For as she prayde, so was don,

In dede; for Juno, right anon,

Called thus her messagere

To do her erande, and he com nere.

Whan he was come, she bad him thus: 135

'Go bet,' quod Juno, 'to Morpheus,

Thou knowest hym wel, the god of sleep;

Now understond wel, and tak keep.

Sey thus on my halfe, that he

Go faste into the grete see, 140

And bid him that, on alle thing,

He take up Seys body the king,

That lyth ful pale and no-thing rody.

Bid him crepe into the body,

And do it goon to Alcyone 145

The quene, ther she lyth alone,

And shewe hir shortly, hit is no nay,

How hit was dreynt this other day;

And do the body speke so

Right as hit was wont to do, 150

The whyles that hit was on lyve.

Go now faste, and hy thee blyve!'

This messager took leve and wente

Upon his wey, and never ne stente

Til he com to the derke valeye 155

That stant bytwene roches tweye,

Ther never yet grew corn ne gras,

Ne tree, ne nothing that ought was,

Beste, ne man, ne nothing elles,

Save ther were a fewe welles 160

Came renning fro the cliffes adoun,

That made a deedly sleping soun,

And ronnen doun right by a cave

That was under a rokke y-grave

Amid the valey, wonder depe. 165

Ther thise goddes laye and slepe,

Morpheus, and Eclympasteyre,

That was the god of slepes heyre,

That slepe and did non other werk.

This cave was also as derk 170

As helle pit over-al aboute;

They had good leyser for to route

To envye, who might slepe beste;

Some henge hir chin upon hir breste

And slepe upright, hir heed y-hed, 175

And some laye naked in hir bed,

And slepe whyles the dayes laste.

This messager come flying faste,

And cryed, 'O ho! Awake anon!'

Hit was for noght; ther herde him non. 180

'Awak!' quod he, 'who is, lyth there?'

And blew his horn right in hir ere,

And cryed `awaketh!' wonder hye.

This god of slepe, with his oon ye

Cast up, axed, 'who clepeth there?' 185

'Hit am I,' quod this messagere;

'Juno bad thou shuldest goon' —

And tolde him what he shulde doon

As I have told yow here-tofore;

Hit is no need reherse hit more; 190

And wente his wey, whan he had sayd.

Anon this god of slepe a-brayd

Out of his slepe, and gan to goon,

And did as he had bede him doon;

Took up the dreynte body sone, 195

And bar hit forth to Alcyone,

His wif the quene, ther-as she lay,

Right even a quarter before day,

And stood right at hir beddes fete,

And called hir, right as she het, 200

By name, and sayde, 'My swete wyf,

Awak! Let be your sorwful lyf!

For in your sorwe there lyth no reed;

For certes, swete, I nam but deed;

Ye shul me never on lyve y-see. 205

But good swete herte, look that ye

Bury my body, at whiche a tyde

Ye mowe hit finde the see besyde;

And far-wel, swete, my worldes blisse!

I praye god your sorwe lisse; 210

To litel whyl our blisse lasteth!'

With that hir eyen up she casteth,

And saw noght; 'A!' quod she, 'for sorwe!'

And deyed within the thridde morwe.

But what she sayde more in that swow 215

I may not telle yow as now,

Hit were to longe for to dwelle;

My first matere I wil yow telle,

Wherfor I have told this thing

Of Alcione and Seys the king. 220

For thus moche dar I saye wel,

I had be dolven everydel,

And deed, right through defaute of sleep,

If I nad red and taken keep

Of this tale next before: 225

And I wol telle yow wherfore:

For I ne might, for bote ne bale,

Slepe, or I had red this tale

Of this dreynte Seys the king,

And of the goddes of sleping. 230

Whan I had red this tale wel

And over-loked hit everydel,

Me thoughte wonder if hit were so;

For I had never herd speke, or tho,

Of no goddes that coude make 235

Men for to slepe, ne for to wake;

For I ne knew never god but oon.

And in my game I sayde anoon —

And yet me list right evel to pleye —

'Rather then that I shulde deye 240

Through defaute of sleping thus,

I wolde yive thilke Morpheus,

Or his goddesse, dame Juno,

Or som wight elles, I ne roghte who —

To make me slepe and have som rest — 245

I wil yive him the alderbest

Yift that ever he abood his lyve,

And here on warde, right now, as blyve;

If he wol make me slepe a lyte,

Of downe of pure dowves whyte 250

I wil yive him a fether-bed,

Rayed with golde, and right wel cled

In fyn blak satin doutremere,

And many a pilow, and every bere

Of clothe of Reynes, to slepe softe; 255

Him thar not nede to turnen ofte.

And I wol yive him al that falles

To a chambre; and al his halles

I wol do peynte with pure golde,

And tapite hem ful many folde 260

Of oo sute; this shal he have,

Yf I wiste wher were his cave,

If he can make me slepe sone,

As did the goddesse Alcione.

And thus this ilke god, Morpheus, 265

May winne of me mo fees thus

Than ever he wan; and to Juno,

That is his goddesse, I shal so do,

I trowe that she shal holde her payd.'

I hadde unnethe that word y-sayd 270

Right thus as I have told hit yow,

That sodeynly, I niste how,

Swich a lust anoon me took

To slepe, that right upon my book

I fil aslepe, and therwith even 275

Me mette so inly swete a sweven,

So wonderful, that never yit

I trowe no man hadde the wit

To conne wel my sweven rede;

No, not Ioseph, withoute drede, 280

Of Egipte, he that redde so

The kinges meting Pharao,

No more than koude the leste of us;

Ne nat scarsly Macrobeus,

(He that wroot al th'avisioun 285

That he mette, Kyng Scipioun,

The noble man, the Affrican —

Swiche marvayles fortuned than)

I trowe, a-rede my dremes even.

Lo, thus hit was, this was my sweven. 290

Me thoughte thus: — that hit was May,

And in the dawning ther I lay,

Me mette thus, in my bed al naked: —

I loked forth, for I was waked

With smale foules a gret hepe, 295

That had affrayed me out of slepe

Through noyse and swetnesse of hir song;

And, as me mette, they sate among,

Upon my chambre-roof withoute,

Upon the tyles, al a-boute, 300

And songen, everich in his wise,

The moste solempne servyse

By note, that ever man, I trowe,

Had herd; for som of hem song lowe,

Som hye, and al of oon acorde. 305

To telle shortly, at oo worde,

Was never y-herd so swete a steven,

But hit had be a thing of heven; —

So mery a soun, so swete entunes,

That certes, for the toune of Tewnes, 310

I nolde but I had herd hem singe,

For al my chambre gan to ringe

Through singing of hir armonye.

For instrument nor melodye

Was nowher herd yet half so swete, 315

Nor of acorde half so mete;

For ther was noon of hem that feyned

To singe, for ech of hem him peyned

To finde out mery crafty notes;

They ne spared not hir throtes. 320

And, sooth to seyn, my chambre was

Ful wel depeynted, and with glas

Were al the windowes wel y-glased,

Ful clere, and nat an hole y-crased,

That to beholde hit was gret Joye. 325

For hoolly al the storie of Troye

Was in the glasing y-wroght thus,

Of Ector and of king Priamus,

Of Achilles and king Lamedon,

Of Medea and of Iason, 330

Of Paris, Eleyne, and Lavyne.

And alle the walles with colours fyne

Were peynted, bothe text and glose,

Of al the Romaunce of the Rose.

My windowes weren shet echon, 335

And through the glas the sonne shon

Upon my bed with brighte bemes,

With many glade gilden stremes;

And eek the welken was so fair,

Blew, bright, clere was the air, 340

And ful atempre for sothe hit was;

For nother cold nor hoot hit nas,

Ne in al the welken was a cloude.

And as I lay thus, wonder loude

Me thoughte I herde an hunte blowe 345

T'assaye his horn, and for to knowe

Whether hit were clere or hors of soune.

I herde goinge, up and doune,

Men, hors, houndes, and other thing;

And al men speken of hunting, 350

How they wolde slee the hert with strengthe,

And how the hert had, upon lengthe,

So moche embosed,I not now what.

Anon-right, whan I herde that,

How that they wolde on hunting goon, 355

I was right glad, and up anoon;

I took my hors, and forth I wente

Out of my chambre; I never stente

Til I com to the feld withoute.

Ther overtook I a gret route 360

Of huntes and eek of foresteres,

With many relayes and lymeres,

And hyed hem to the forest faste,

And I with hem; — so at the laste

I asked oon, ladde a lymere: — 365

'Say, felow, who shal hunten here'

Quod I, and he answerde ageyn,

'Sir, th'emperour Octovien,'

Quod he, `and is heer faste by.'

'A goddes halfe, in good tyme,' quod I, 370

'Go we faste!' and gan to ryde.

Whan we came to the forest-syde,

Every man dide, right anoon,

As to hunting fil to doon.

The mayster-hunte anoon, fot-hoot, 375

With a gret horne blew three moot

At the uncoupling of his houndes.

Within a whyl the hert y-founde is,

Y-halowed, and rechased faste

Longe tyme; and so at the laste, 380

This hert rused and stal away

Fro alle the houndes a prevy way.

The houndes had overshote hem alle,

And were on a defaute y-falle;

Therwith the hunte wonder faste 385

Blew a forloyn at the laste.

I was go walked fro my tree,

And as I wente, ther cam by me

A whelp, that fauned me as I stood,

That hadde y-folowed, and koude no good. 390

Hit com and creep to me as lowe,

Right as hit hadde me y-knowe,

Hild doun his heed and joyned his eres,

And leyde al smothe doun his heres.

I wolde han caught hit, and anoon 395

Hit fledde, and was fro me goon;

And I him folwed, and hit forth wente

Doun by a floury grene wente

Ful thikke of gras, ful softe and swete,

With floures fele, faire under fete, 400

And litel used, hit seemed thus;

For bothe Flora and Zephirus,

They two that make floures growe,

Had mad hir dwelling ther, I trowe;

For hit was, on to beholde, 405

As thogh the erthe envye wolde

To be gayer than the heven,

To have mo floures, swiche seven

As in the welken sterres be.

Hit had forgete the povertee 410

That winter, through his colde morwes,

Had mad hit suffren, and his sorwes;

Al was forgeten, and that was sene.

For al the wode was waxen grene,

Swetnesse of dewe had mad it waxe. 415

Hit is no need eek for to axe

Wher ther were many grene greves,

Or thikke of trees, so ful of leves;

And every tree stood by himselve

Fro other wel ten foot or twelve. 420

So grete trees, so huge of strengthe,

Of fourty or fifty fadme lengthe,

Clene withoute bough or stikke,

With croppes brode, and eek as thikke —

They were nat an inche asonder — 425

That hit was shadwe overal under;

And many an hert and many an hynde

Was both before me and bihinde.

Of founes, soures, bukkes, does

Was ful the wode, and many roes, 430

And many squirelles that sete

Ful hye upon the trees, and ete,

And in hir maner made festes.

Shortly, hit was so ful of bestes,

That thogh Argus, the noble countour, 435

Sete to rekene in his countour,

And rekene with his figures ten —

For by tho figures mowe al ken,

If they be crafty, rekene and noumbre,

And telle of every thing the noumbre — 440

Yet shulde he fayle to rekene even

The wondres, me mette in my sweven.

But forth they romed wonder faste

Doun the wode; so at the laste

I was war of a man in blak, 445

That sat and had yturned his bak

To an ook, an huge tree.

'Lord,' thoghte I, 'who may that be?

What ayleth him to sitten here?'

Anoon-right I wente nere; 450

Than fond I sitte even upright

A wonder wel-faringe knight —

By the maner me thoughte so —

Of good mochel, and yong therto,

Of the age of four and twenty yeer. 455

Upon his berde but litel heer,

And he was clothed al in blakke.

I stalked even unto his bakke,

And ther I stood as stille as ought,

That, sooth to saye, he saw me nought, 460

For-why he heng his heed adoune.

And with a deedly sorwful soune

He made of ryme ten vers or twelve

Of a compleynt to himselve,

The moste pite, the moste routhe, 465

That ever I herde; for, by my trouthe,

Hit was gret wonder that nature

Might suffren any creature

To have swich sorwe, and be not deed.

Ful pitous, pale, and nothing reed, 470

He sayde a lay, a maner song,

Withoute note, withoute song,

And hit was this; for wel I can

Reherce hit; right thus hit began. —

'I have of sorwe so grete won, 475

That Joye gete I never non,

Now that I see my lady bright,

Which I have loved with al my might,

Is fro me dedd, and is a-goon.

And thus in sorwe lefte me alone. 480

'Allas, o deeth! What ayleth thee,

That thou noldest have taken me,

'Whan that thou toke my lady swete?

That was so fayr, so fresh, so free,

So good, that men may wel y-see 485

'Of al goodnesse she had no mete!' —

Whan he had mad thus his complaynte,

His sorowful herte gan faste faynte,

And his spirites wexen dede;

The blood was fled, for pure drede, 490

Doun to his herte, to make him warm —

For wel hit feled the herte had harm —

To wite eek why hit was adrad,

By kinde, and for to make hit glad;

For hit is membre principal 495

Of the body; and that made al

His hewe chaunge and wexe grene

And pale, for no blood was sene

In no maner lime of his.

Anoon therwith whan I saugh this, 500

He ferde thus evel ther he sete,

I wente and stood right at his fete,

And grette him, but he spak noght,

But argued with his owne thoght,

And in his witte disputed faste 505

Why and how his lyf might laste;

Him thoughte his sorwes were so smerte

And lay so colde upon his herte;

So, through his sorwe and hevy thoght,

Made him that he ne herde me noght; 510

For he had wel nigh lost his minde,

Thogh Pan, that men clepeth god of kinde,

Were for his sorwes never so wrooth.

But at the laste, to sayn right sooth,

He was war of me, how I stood 515

Before him, and dide of myn hood,

And grette him, as I best koude.

Debonairly, and nothing loude,

He sayde, `I prey thee, be not wrooth,

I herde thee not, to sayn the sooth, 520

Ne I saw thee not, sir, trewely.'

'A! goode sir, no fors,' quod I,

'I am right sory if I have ought

Destroubled yow out of your thought;

Foryive me if I have mistake.' 525

'Yis, th'amendes is light to make,'

Quod he, `for ther lyth noon ther-to;

Ther is nothing missayd nor do,'

Lo! how goodly spak this knight,

As it had been another wight; 530

He made it nouther tough ne queynte

And I saw that, and gan me aqueynte

With him, and fond him so tretable,

Right wonder skilful and resonable,

As me thoghte, for al his bale. 535

Anoon-right I gan finde a tale

To him, to loke wher I might ought

Have more knowing of his thought.

'Sir,' quod I, `this game is doon;

I holde that this hert be goon; 540

Thise huntes conne him nowher see.'

'I do no fors therof,' quod he,

'My thought is theron never a deel.'

'By oure lord,' quod I, `I trowe yow weel,

Right so me thinketh by your chere. 545

But, sir, oo thing wol ye here?

Me thinketh, in gret sorwe I yow see;

But certes, good sir, yif that ye

Wolde ought discure me your wo,

I wolde, as wis god help me so, 550

Amende hit, yif I can or may;

Ye mowe preve hit by assay.

For, by my trouthe, to make yow hool,

I wol do al my power hool;

And telleth me of your sorwes smerte, 555

Paraventure hit may ese your herte,

That semeth ful seke under your syde.'

With that he loked on me asyde,

As who sayth, `Nay, that wol not be.'

'Graunt mercy, goode frend,' quod he, 560

'I thanke thee that thou woldest so,

But hit may never the rather be do,

No man may my sorwe glade,

That maketh my hewe to falle and fade,

And hath myn understonding lorn, 565

That me is wo that I was born!

May noght make my sorwes slyde,

Nought the remedies of Ovyde;

Ne Orpheus, god of melodye,

Ne Dedalus, with playes slye; 570

Ne hele me may phisicien,

Noght Ypocras, ne Galien;

Me is wo that I live houres twelve;

But who so wol assaye himselve

Whether his herte can have pite 575

Of any sorwe, lat him see me.

I wrecche, that deeth hath mad al naked

Of alle blisse that ever was maked,

Y-worthe worste of alle wightes,

That hate my dayes and my nightes; 580

My lyf, my lustes be me looth,

For al welfare and I be wrooth.

The pure deeth is so my fo

Thogh I wolde deye, hit wolde not so;

For whan I folwe hit, hit wol flee; 585

I wolde have hit, hit nil not me.

This is my peyne withoute reed,

Alway deinge and be not deed,

That Sesiphus, that lyth in helle,

May not of more sorwe telle. 590

And who so wiste al, be my trouthe,

My sorwe, but he hadde routhe

And pite of my sorwes smerte,

That man hath a feendly herte.

For who so seeth me first on morwe 595

May seyn, he hath y-met with sorwe;

For I am sorwe and sorwe is I.

'Allas! and I wol telle the why;

My song is turned to pleyning,

And al my laughter to weping, 600

My glade thoghtes to hevynesse,

In travaile is myn ydelnesse

And eek my reste; my wele is wo,

My goode is harm, and ever-mo

In wrathe is turned my pleying, 605

And my delyt into sorwing.

Myn hele is turned into seeknesse,

In drede is al my sikernesse.

To derke is turned al my light,

My wit is foly, my day is night, 610

My love is hate, my sleep waking,

My mirthe and meles is fasting,

My countenaunce is nycete,

And al abaved wherso I be,

My pees, in pleding and in werre; 615

Allas, how mighte I fare werre?

'My boldnesse is turned to shame,

For fals Fortune hath pleyd a game

Atte ches with me, allas, the whyle!

The trayteresse fals and ful of gyle, 620

That al behoteth and nothing halt,

She goth upryght and yet she halt,

That baggeth foule and loketh faire,

The dispitouse debonaire,

That scorneth many a creature! 625

An ydole of fals portraiture

Is she, for she wil sone wryen;

She is the monstres heed ywryen,

As filth over ystrawed with floures;

Hir moste worship and hir flour is 630

To lyen, for that is hir nature;

Withoute feyth, lawe, or mesure.

She is fals; and ever laughinge

With oon eye, and that other wepinge.

That is broght up, she set al doun. 635

I lykne hir to the scorpioun,

That is a fals, flateringe beste;

For with his hede he maketh feste,

But al amid his flateringe

With his tayle he wol stinge, 640

And envenyme; and so wol she.

She is th'envyouse charite

That is ay fals, and seemeth weel,

So turneth she hir false wheel

Aboute, for it is nothing stable, 645

Now by the fyre, now at table;

Ful many oon hath she thus yblent;

She is pley of enchauntement,

That semeth oon and is not so,

The false theef! What hath she do, 650

Trowest thou? By our Lord, I wol thee seye.

Atte ches with me she gan to pleye;

With hir false draughtes divers

She stal on me, and took my fers.

And whan I saw my fers aweye, 655

Alas! I couthe no lenger playe,

But seyde, "Farewel, swete, y-wis,

And farwel al that ever ther is!"

Therwith Fortune seyde, "Chek her!"

And "Mate!" in mid pointe of the chekker 660

With a poune erraunt, allas!

Ful craftier to pley she was

Than Athalus, that made the game

First of the ches: so was his name.

But God wolde I had ones or twyes 665

Y-koud and knowe the jeupardyes

That koude the Grek Pithagores!

I shulde have pleyd the bet at ches,

And kept my fers the bet therby;

And thogh wherto? for trewely, 670

I hold that wish nat worth a stree!

Hit had be never the bet for me.

For Fortune can so many a wyle,

Ther be but fewe can hir begyle,

And eek she is the las to blame; 675

Myself I wolde have do the same,

Before god, hadde I been as she;

She oghte the more excused be.

For this I say yet more therto,

Hadde I be god and mighte have do 680

My wille, whan she my fers caughte,

I wolde have drawe the same draughte.

For, also wis god yive me reste,

I dar wel swere she took the beste!

'But through that draughte I have lorn 685

My blisse; allas! that I was born!

For evermore, I trowe trewly,

For al my wil, my lust hoolly

Is turned; but yet what to done?

Be oure Lord, hit is to deye sone; 690

For nothing I ne leve it noght,

But live and deye right in this thoght.

There nis planete in firmament,

Ne in air, ne in erthe, noon element,

That they ne yive me a yift echoon 695

Of weping, whan I am aloon.

For whan that I avyse me weel,

And bethenke me everydeel,

How that ther lyth in rekening,

In my sorwe for nothing; 700

And how ther leveth no gladnesse

May gladde me of my distresse,

And how I have lost suffisance,

And therto I have no plesance,

Than may I say, I have right noght. 705

And whan al this falleth in my thoght,

Allas! than am I overcome!

For that is doon is not to come!

I have more sorowe than Tantale.'

And whan I herde him telle this tale 710

Thus pitously, as I yow telle,

Unnethe mighte I lenger dwelle,

Hit dide myn herte so moche wo.

'A! good sir!' quod I, 'say not so!

Have som pite on your nature 715

That formed yow to creature,

Remembre yow of Socrates;

For he ne counted nat three strees

Of noght that Fortune coude do.'

'No,' quod he, 'I can not so.' 720

'Why so, good sir! Pardee!' quod I;

'Ne say noght so, for trewely,

Thogh ye had lost the ferses twelve,

And ye for sorwe mordred yourselve,

Ye sholde be dampned in this cas 725

By as good right as Medea was,

That slow hir children for Jason;

And Phyllis als for Demophon

Heng hirself, so weylaway!

For he had broke his terme-day 730

To come to hir. Another rage

Had Dydo, quene eek of Cartage,

That slow hirself for Eneas

Was fals; a whiche a fool she was!

And Ecquo dyed for Narcisus. 735

Nolde nat love hir; and right thus

Hath many another foly don.

And for Dalida died Sampson,

That slow himself with a pilere.

But ther is noon alyve here 740

Wolde for a fers make this wo!'

'Why so?' quod he; 'hit is nat so,

Thou woste ful litel what thou menest;

I have lost more than thow wenest.'

'Lo, sir, how may that be?' quod I; 745

'Good sir, tel me al hoolly

In what wyse, how, why, and wherfore

That ye have thus your blisse lore,'

'Blythly,' quod he, 'com sit adoun,

I telle thee up condicioun 750

That thou hoolly, with al thy wit,

Do thyn entente to herkene hit.'

'Yis, sir.' 'Swere thy trouthe therto.'

'Gladly.' 'Do than holde herto!'

'I shal right blythly, so God me save, 755

Hoolly, with al the wit I have,

Here yow, as wel as I can,'

'A goddes half!' quod he, and began: —

'Sir,' quod he, `sith first I couthe

Have any maner wit fro yowthe, 760

Or kyndely understonding

To comprehende, in any thing,

What love was, in myn owne wit,

Dredelees, I have ever yit

Be tributary, and yiven rente 765

To love hoolly with goode entente,

And through plesaunce become his thral,

With good wil, body, herte, and al.

Al this I putte in his servage,

As to my lorde, and dide homage; 770

And ful devoutly prayde him to,

He shulde besette myn herte so,

That it plesaunce to him were,

And worship to my lady dere.

'And this was longe, and many a yeer 775

Or that myn herte was set o-wher,

That I did thus, and niste why;

I trowe hit cam me kindely.

Paraunter I was therto most able

As a whyt wal or a table; 780

For hit is redy to cacche and take

Al that men wil therin make,

Wherso so men wol portreye or peynte,

Be the werkes never so queynte.

'And thilke tyme I ferde so 785

I was able to have lerned tho,

And to have coud as wel or better,

Paraunter, other art or letter.

But for love cam first in my thought,

Therfore I forgat hit nought. 790

I chees love to my firste craft,

Therfor hit is with me laft.

Forwhy I took hit of so yong age,

That malice hadde my corage

Nat that tyme turned to nothing 795

Through to mochel knowleching.

For that tyme yowthe, my maistresse,

Governed me in ydelnesse;

For hit was in my firste youthe,

And tho ful litel good I couthe, 800

For al my werkes were flittinge,

And al my thoghtes varyinge;

Al were to me yliche good,

That I knew tho; but thus hit stood.

'Hit happed that I cam on a day 805

Into a place, ther I say,

Trewly, the fayrest companye

Of ladies that ever man with ye

Had seen togedres in oo place.

Shal I clepe hit hap other grace 810

That broght me ther? Nay, but Fortune,

That is to lyen ful comune,

The false trayteresse, pervers,

God wolde I coude clepe hir wers!

For now she worcheth me ful wo, 815

And I wol telle sone why so.

'Among thise ladies thus echoon,

Soth to seyn, I saw ther oon

That was lyk noon of al the route;

For I dar swere, withoute doute, 820

That as the someres sonne bright

Is fairer, clere, and hath more light

Than any planete, is in heven,

The mone, or the sterres seven,

For al the worlde so had she 825

Surmounted hem alle of beaute,

Of maner and of comlynesse,

Of stature and wel set gladnesse,

Of goodlihede so wel beseye —

Shortly, what shal I more seye? 830

By God, and by his halwes twelve,

It was my swete, right al hirselve!

She had so stedfast countenaunce,

So noble port and meyntenaunce.

And Love, that had herd my boone, 835

Had espyed me thus soone,

That she ful sone, in my thoght,

As helpe me God, so was ycaught

So sodenly, that I ne took

No maner reed but at hir look 840

And at myn herte; for-why hir eyen

So gladly, I trow, myn herte seyen,

That purely tho myn owne thoght

Seyde hit were bet serve hir for noght

Than with another to be weel. 845

And hit was sooth, for, everydeel,

I wil anoon-right telle thee why.

I saw hir daunce so comlily,

Carole and singe so swetely,

Laughe and pleye so womanly, 850

And loke so debonairly,

So goodly speke and so frendly,

That certes, I trow, that evermore

Nas seyn so blisful a tresore.

For every heer upon hir hede, 855

Soth to seyn, hit was not rede,

Ne nouther yelow, ne broun hit nas;

Me thoghte, most lyk gold hit was.

And whiche eyen my lady hadde!

Debonair, goode, glade, and sadde, 860

Simple, of good mochel, noght to wyde;

Therto hir look nas not asyde,

Ne overthwert, but beset so weel,

Hit drew and took up, everydeel,

Alle that on hir gan beholde. 865

Hir eyen semed anoon she wolde

Have mercy; fooles wenden so;

But hit was never the rather do.

Hit nas no countrefeted thing,

It was hir owne pure loking, 870

That the goddesse, dame Nature,

Had made hem opene by mesure,

And close; for, were she never so glad,

Hir loking was not foly sprad,

Ne wildely, thogh that she pleyde; 875

But ever, me thoght, hir eyen seyde,

"By god, my wrathe is al for-yive!"

'Therwith hir liste so wel to live,

That dulnesse was of hir adrad.

She nas to sobre ne to glad; 880

In alle thinges more mesure

Had never, I trowe, creature.

But many oon with hir loke she herte,

And that sat hir ful lyte at herte,

For she knew nothing of her thoght; 885

But whether she knew, or knew hit noght,

Algate she ne roghte of hem a stree!

To gete hir love no ner was he

That woned at home, than he in Inde;

The formest was alway behinde. 890

But goode folk, over al other,

She loved as man may do his brother;

Of whiche love she was wonder large,

In skilful places that bere charge.

'Which a visage had she therto! 895

Allas! myn herte is wonder wo

That I ne can discryven hit!

Me lakketh bothe English and wit

For to undo hit at the fulle;

And eek my spirits be so dulle 900

So greet a thing for to devyse.

I have no wit that can suffyse

To comprehenden hir beaute;

But thus moche dar I seyn, that she

Was rody, fresh, and lyvely hewed; 905

And every day hir beaute newed.

And negh hir face was alderbest;

For certes, Nature had swich lest

To make that fair, that trewly she

Was hir cheef patron of beautee, 910

And cheef ensample of al hir werke,

And moustre; for, be hit never so derke,

Me thinketh I see hir ever-mo.

And yet more-over, thogh alle tho

That ever lived were not alyve, 915

They ne sholde have founde to discryve

In al hir face a wikked signe;

For hit was sad, simple, and benigne.

'And which a goodly, softe speche

Had that swete, my lyves leche! 920

So frendly, and so wel y-grounded,

Up al resoun so wel y-founded,

And so tretable to alle gode,

That I dar swere by the rode,

Of eloquence was never founde 925

So swete a sowninge facounde,

Ne trewer tonged, ne scorned lasse,

Ne bet coude hele; that, by the masse,

I durste swere, thogh the pope hit songe,

That ther was never yet through hir tonge 930

Man ne woman gretly harmed;

As for hir, ther was al harm hid;

Ne lasse flatering in hir worde,

That purely, hir simple recorde

Was founde as trewe as any bonde, 935

Or trouthe of any mannes honde.

Ne chyde she koude never a deel,

That knoweth al the world ful weel.

`But swich a fairnesse of a nekke

Had that swete that boon nor brekke 940

Nas ther non sene, that missat.

Hit was whyt, smothe, streght, and flat,

Withouten hole; and canel-boon,

As by seming, had she noon.

Hir throte, as I have now memoire, 945

Semed a round tour of yvoire,

Of good gretnesse, and noght to grete.

'And goode faire Whyte she hete,

That was my lady name right.

She was bothe fair and bright, 950

She hadde not hir name wrong.

Right faire shuldres, and body long

She hadde, and armes; every lith

Fattish, flesshy, not greet therwith;

Right whyte handes, and nayles rede, 955

Rounde brestes; and of good brede

Hyr hippes were, a streight flat bake.

I knew on hir non other lak

That al hir limmes nere sewing,

In as fer as I had knowing. 960

'Therto she koude so wel pleye,

Whan that hir liste, that I dar seye,

That she was lyk to torche bright,

That every man may take of light

Ynogh, and hit hath never the lesse. 965

'Of maner and of comlinesse

Right so ferde my lady dere;

For every wight of hir manere

Might cacche ynogh, if that he wolde,

If he had eyen hir to beholde. 970

For I dar sweren, if that she

Had among ten thousand be,

She wolde have be, at the leste,

A cheef mirour of al the feste,

Thogh they had stonden in a rowe, 975

To mennes eyen koude have knowe.

For wher-so men had pleyd or waked,

Me thoghte the felawship as naked

Withouten hir, that saw I ones,

As a coroune withoute stones. 980

Trewely she was, to myn ye,

The soleyn fenix of Arabye,

For ther liveth never but oon;

Ne swich as she ne know I noon.

'To speke of goodnesse; trewly she 985

Had as moche debonairte

As ever had Hester in the bible

And more, if more were possible.

And, soth to seyne, therwithal

She had a wit so general, 990

So hool enclyned to alle gode,

That al hir wit was set, by the rode,

Withoute malice, upon gladnesse;

Therto I saw never yet a lesse

Harmul, than she was in doing. 995

I sey nat that she ne had knowing

What harm was; or elles she

Had coud no good, so thinketh me.

'And trewely, for to speke of trouthe,

But she had had, hit had be routhe. 1000

Therof she had so moche hir del —

And I dar seyn and swere hit wel —

That Trouthe him-self, over al and al,

Had chose his maner principal

In hir, that was his resting-place. 1005

Therto she hadde the moste grace,

To have stedfast perseveraunce,

And esy, atempre governaunce,

That ever I knew or wiste yit;

So pure suffraunt was hir wit. 1010

And reson gladly she understood,

Hit folowed wel she coude good.

She used gladly to do weel;

These were hir maners everydeel.

'Therwith she loved so wel right, 1015

She wrong do wolde to no wight;

No wight might do hir no shame,

She loved so wel hir owne name.

Hir luste to holde no wight in honde;

Ne, be thou siker, she nolde fonde 1020

To holde no wight in balaunce,

By half word ne by countenaunce,

But-if men wolde upon hir lye;

Ne sende men into Walakye,

To Pruyse, and into Tartarye, 1025

To Alisaundre, ne into Turkye,

And bidde him faste, anoon that he

Go hoodles to the drye see,

And come hoom by the Carrenare;

And seye, "Sir, be now right ware 1030

That I may of yow here seyn

Worship, or that ye come ageyn!'

She ne used no suche knakkes smale.

'But wherfor that I telle my tale?

Right on this same, as I have seyd, 1035

Was hoolly al my love leyd;

For certes, she was, that swete wyf,

My suffisaunce, my lust, my lyf,

Myn hap, myn hele, and al my blisse,

My worldes welfare, and my lisse, 1040

And I hires hoolly, everydeel.'

'By our lord,' quod I, 'I trowe yow weel!

Hardily, your love was wel beset,

I not how ye mighte have do bet.'

'Bet? ne no wight so wel!' quod he. 1045

'I trowe hit, sir,' quod I, 'parde!'

'Nay, leve hit wel!' 'Sir, so do I;

I leve yow wel, that trewely

Yow thoghte, that she was the beste,

And to beholde the alderfaireste, 1050

Who so had loked hir with your eyen.'

'With myn? Nay, alle that hir seyen

Seyde and sworen hit was so.

And thogh they ne hadde, I wolde tho

Have loved best my lady fre, 1055

Thogh I had had al the beautee

That ever had Alcipyades,

And al the strengthe of Ercules,

And therto had the worthinesse

Of Alisaundre, and al the richesse 1060

That ever was in Babiloyne,

In Cartage, or in Macedoyne,

Or in Rome, or in Ninive;

And therto also hardy be

As was Ector, so have I Ioye, 1065

That Achilles slow at Troye —

And therfor was he slayn also

In a temple, for bothe two

Were slayn, he and Antilegius,

And so seyth Dares Frigius, 1070

For love of hir Polixena —

Or ben as wys as Minerva,

I wolde ever, withoute drede,

Have loved hir, for I moste nede!

"Nede!" nay, I gabbe now, 1075

Noght "nede", and I wol telle how,

For of good wille myn herte hit wolde,

And eek to love hir I was holde

As for the fairest and the beste.

'She was as good, so have I reste, 1080

As ever was Penelope of Grece,

Or as the noble wyf Lucrece,

That was the beste — he telleth thus,

The Romayn Tytus Livius —

She was as good, and no-thing lyke, 1085

Thogh hir stories be autentyke;

Algate she was as trewe as she.

'But wherfor that I telle thee

Whan I first my lady say?

I was right yong, the sooth to sey, 1090

And ful gret need I hadde to lerne;

Whan my herte wolde yerne

To love, it was a greet empryse.

But as my wit koude best suffyse,

After my yonge childly wit, 1095

Withoute drede, I besette hit

To love hir in my beste wise,

To do hir worship and servyse

That I tho coude, be my trouthe,

Withoute feyning outher slouthe; 1100

For wonder fayn I wolde hir see.

So mochel hit amended me,

That, whan I saugh hir first a-morwe,

I was warished of al my sorwe

Of al day after, til hit were eve; 1105

Me thoghte nothing mighte me greve,

Were my sorwes never so smerte.

And yit she sit so in myn herte,

That, by my trouthe, I nolde noghte,

For al this worlde, out of my thoght 1110

Leve my lady; no, trewely!'

'Now, by my trouthe, sir,' quod I,

'Me thinketh ye have such a chaunce

As shrift withoute repentaunce.'

'Repentaunce! Nay, fy,' quod he; 1115

'Shulde I now repente me

To love? nay, certes, than were I wel

Wers than was Achitofel,

Or Anthenor, so have I Ioye,

The traytour that betraysed Troye, 1120

Or the false Genelon,

He that purchased the treson

Of Rowland and of Olivere.

Nay, why! I am alyve here

I nil foryete hir never mo.' 1125

'Now, goode sir,' quod I right tho,

'Ye han wel told me here before.

It is no need reherce hit more

How ye sawe hir first, and where;

But wolde ye telle me the manere, 1130

To hir which was your firste speche —

Therof I wolde yow be-seche —

And how she knewe first your thoght,

Whether ye loved hir or noght,

And telleth me eek what ye have lore; 1135

I herde yow telle her-before.'

'Ye,' seyde he,'thow nost what thou menest;

I have lost more than thou wenest.'

'What los is that, sir?' quod I tho;

'Nil she not love yow? Is hit so? 1140

Or have ye oght y-doon amis,

That she hath left yow? Is hit this?

For goddes love, telle me al.'

'Before god,' quod he, 'and I shal.

I saye right as I have seyd, 1145

On hir was al my love leyd;

And yet she niste hit never a deel

Noght longe tyme, leve hit weel.

For be right siker, I durste noght

For al this worlde telle hir my thoght, 1150

Ne I wolde have wratthed hir, trewely.

For wostow why? she was lady

Of the body; she had the herte,

And who hath that, may not asterte.

'But, for to kepe me fro ydelnesse, 1155

Trewely I did my besinesse

To make songes, as I best koude,

And ofte tyme I song hem loude;

And made songes a gret del,

Al-thogh I coude not make so wel 1160

Songes, ne knowe the art al,

As coude Lamekes sone Tubal,

That fond out first the art of songe;

For, as his brothers hamers ronge

Upon his anvelt up and doun, 1165

Therof he took the firste soun;

But Grekes seyn, Pictagoras,

That he the firste finder was

Of the art; Aurora telleth so,

But therof no fors, of hem two. 1170

Algates songes thus I made

Of my feling, myn herte to glade;

And lo! this was the alderfirst,

I not wher that hit were the werst. —

"Lord, hit maketh myn herte light, 1175

Whan I thenke on that swete wight

That is so semely on to see;

And wisshe to god hit might so be,

That she wolde holde me for hir knight,

My lady, that is so fair and bright!" — 1180

'Now have I told thee, sooth to saye,

My firste song. Upon a daye

I bethoghte me what wo

And sorwe that I suffred tho

For hir, and yet she wiste hit noght, 1185

Ne telle hir durste I nat my thoght.

'Allas!' thoghte I, 'I can no reed;

And, but I telle hir, I nam but deed;

And if I telle hir, to seye sooth,

I am adrad she wol be wrooth; 1190

Allas! what shal I thanne do?"

'In this debat I was so wo,

Me thoghte myn herte braste a-tweyn!

So atte laste, soth to sayn,

I me bethoghte that nature 1195

Ne formed never in creature

So moche beautee, trewely,

And bountee, withouten mercy.

'In hope of that, my tale I tolde,

With sorwe, as that I never sholde; 1200

For nedes, and, maugree my heed,

I moste have told hir or be deed.

I not wel how that I began,

Ful evel rehercen hit I can;

And eek, as helpe me god withal, 1205

I trowe hit was in the dismal,

That was the ten woundes of Egipte;

For many a word I over-skipte

In my tale, for pure fere

Lest my wordes misset were. 1210

With sorweful herte, and woundes dede,

Softe and quaking for pure drede

And shame, and stinting in my tale

For ferde, and myn hewe al pale,

Ful ofte I wex bothe pale and reed; 1215

Bowing to hir, I heng the heed;

I durste nat ones loke hir on,

For wit, manere, and al was gon.

I seyde "mercy!" and no more;

Hit nas no game, hit sat me sore. 1220

'So atte laste, sooth to seyn,

Whan that myn herte was come ageyn,

To telle shortly al my speche,

With hool herte I gan hir beseche

That she wolde be my lady swete; 1225

And swor, and gan hir hertely hete

Ever to be stedfast and trewe,

And love hir alwey freshly newe,

And never other lady have,

And al hir worship for to save 1230

As I best koude; I swor hir this —

"For youres is al that ever ther is

For evermore, myn herte swete!

And never false yow, but I mete,

I nil, as wis God helpe me so!" 1235

'And whan I had my tale y-do,

God woot, she acounted nat a stree

Of al my tale, so thoghte me.

To telle shortly as hit is,

Trewely hir answere, hit was this; 1240

I can not now wel counterfete

Hir wordes, but this was the grete

Of hir answere: she sayde, "nay"

Al outerly. Allas, that day

The sorwe I suffred, and the wo! 1245

That trewely Cassandra, that so

Bewayled the destruccioun.

Of Troye and of Ilioun,

Had never swich sorwe as I tho.

I durste no more say therto 1250

For pure fere, but stal away;

And thus I lived ful many a day;

That trewely, I hadde no need

Ferther than my beddes heed

Never a day to seche sorwe; 1255

I fond hit redy every morwe,

For-why I loved hir in no gere.

'So hit befel, another yere,

I thoughte ones I wolde fonde

To do hir knowe and understonde 1260

My wo; and she wel understood

That I ne wilned thing but good,

And worship, and to kepe hir name

Over al thing, and drede hir shame,

And was so besy hir to serve; — 1265

And pite were I shulde sterve,

Sith that I wilned noon harm, y-wis.

So whan my lady knew al this,

My lady yaf me al hoolly

The noble yift of hir mercy, 1270

Saving hir worship, by al weyes;

Dredelees, I mene noon other weyes.

And therwith she yaf me a ring;

I trowe hit was the firste thing;

But if myn herte was ywaxe 1275

Glad, that is no need to axe!

As helpe me God, I was as blyve,

Reysed, as fro dethe to lyve,

Of alle happes the alderbeste,

The gladdest and the moste at reste. 1280

For trewely, that swete wight,

Whan I had wrong and she the right,

She wolde alwey so goodely

For-yeve me so debonairly.

In alle my youthe, in alle chaunce, 1285

She took me in hir governaunce.

Therwith she was alway so trewe,

Our joye was ever yliche newe;

Our hertes wern so even a payre,

That never nas that oon contrayre 1290

To that other, for no wo.

For sothe, yliche they suffred tho

Oo blisse and eek oo sorwe bothe;

Yliche they were bothe gladde and wrothe;

Al was us oon, withoute were. 1295

And thus we lived ful many a yere

So wel, I can nat telle how.'

'Sir,' quod I, 'where is she now?'

'Now!' quod he, and stinte anoon.

Therwith he wex as deed as stoon, 1300

And seyde, 'Allas! that I was bore,

That was the los, that here before

I tolde thee, that I had lorn.

Bethenk how I seyde here beforn,

"Thou wost ful litel what thou menest; 1305

I have lost more than thou wenest" —

God woot, allas! Right that was she!'

'Allas! sir, how? What may that be?'

'She is deed!' 'Nay!' 'Yis, by my trouthe!'

'Is that your los? By god, hit is routhe!' 1310

And with that worde, right anoon,

They gan to strake forth; al was doon,

For that tyme, the hert-hunting.

With that, me thoghte, that this king

Gan quikly hoomward for to ryde 1315

Unto a place ther besyde,

Which was from us but a lyte,

A long castel with walles whyte,

Be seynt Johan! on a riche hil,

As me mette; but thus it fil. 1320

Right thus me mette, as I yow telle,

That in the castel was a belle,

As hit had smiten houres twelve. —

Therwith I awook myselve,

And fond me lying in my bed; 1325

And the book that I had red,

Of Alcyone and Seys the king,

And of the goddes of sleping,

I fond it in myn honde ful even.

Thoghte I, 'this is so queynt a sweven, 1330

That I wol, be processe of tyme,

Fonde to putte this sweven in ryme

As I can best, and that anoon.' —

This was my sweven; now hit is doon.