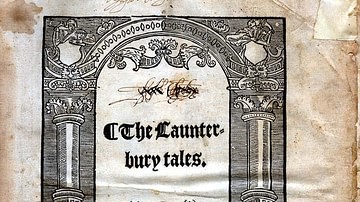

In Geoffrey Chaucer's first major work, The Book of the Duchess (c. 1370 CE), two genres of medieval literature are combined – the French poetic convention of courtly love and the high medieval dream vision – to create a poem of enduring power on the theme of grief. The piece was composed for Chaucer's friend John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster (l. 1340-1399 CE) in honor of his late wife Blanche (l. 1342-1368 CE) who died, most likely of plague, at the age of 26. John of Gaunt mourned her loss for the rest of his life, observing the date of her death every year, and may have commissioned the poem for Blanche's memorial service on the two-year anniversary of his loss. Chaucer's work was clearly appreciated by John of Gaunt as he rewarded Chaucer for it with a grant of ten pounds a year for life, at that time equal to almost a year's salary.

Although Chaucer was working in the forms of established genres, he departs from both significantly to make two points regarding grief:

- No one's grief is any more or any less significant than another's.

- There is no quick-fix for grief and one can only endure and learn to live with the loss.

The tradition of courtly love held that there was a hierarchy of grief while the high medieval dream vision consistently presented a worldview in which an individual could be consoled and find closure to a problem through a dream, sent by God, which resolved the issue. Chaucer draws on both traditions in depicting a grieving knight and the sympathetic narrator who attempts to console him and, in doing so, inverts their central visions and values to provide a reader with insight into the depths of grief and the limits of consolation.

Summary

The poem opens with the narrator complaining that he cannot sleep, has not slept in eight years, and suffers from a sickness of the heart. He never explicitly states that he is suffering from a broken heart but says there is only one physician who can heal him but will not do so (lines 39-40). The image of the noble lady, the object of one's affection, as a physician who can hurt or heal was established by the courtly love tradition, and Chaucer writes with the understanding his audience knows this. The 'physician' here is a woman the narrator loves, and he is suffering from unrequited love, most likely in the form of an unfaithful lover.

Unable to sleep, the narrator begins to read Ovid and the story of Alcyone and Seys (commonly given as Ceyx), two lovers parted by death. Ceyx has gone on a sea voyage and, when he does not return in time, Alcyone begins to worry and then is tormented by the fear that he has died. She prays to Juno to at least give her some answer and, in a dream, the god of sleep Morpheus appears as Ceyx to tell her he is dead and she will find his body washed up on the shore. Alcyone dies of grief three days after Ceyx appears to her. The narrator is amazed that Alcyone should pray to a pagan goddess and get an answer when, for the past eight years, he has gotten no answer to his prayers. He immediately prays to Juno for help and almost instantly falls asleep.

He dreams he wakes up in a May morning in bed and, hearing a hunt in progress below, goes to join in. He mounts a horse and follows the hunt into the wood but becomes separated from the rest of the party and is walking on foot when he comes upon a knight in black sitting alone and composing a poem about lost love in which he says how his "lady bright" is dead and he has lost everything because she was without equal and can never be replaced (lines 475-486). The narrator thinks he is just composing a 'complaint', a formal type of verse in which a poet draws upon established conceits and images for effect. He understands, however, that the knight is genuinely upset (although he does not know the cause) and sits down to console him.

Throughout the rest of the poem, until almost the very end, the knight talks about his memories of his wife and his grief over her loss and the narrator fails to grasp that the poem the knight was writing earlier is about his own situation. The narrator, dealing with his own type of heartache, continually thinks the knight is talking about unrequited love or an unfaithful lover, repeatedly giving examples of loss in life and how famous lovers have coped until the knight clearly tells him his lady is dead and the narrator sympathizes (lines 1300-1310). Directly after this, the horns sound ending the hunt and the narrator wakes.

He finds himself in bed holding Ovid's book but remembers the dream exactly and says how it was so amazing he will have to write it down immediately. The poem ends with the narrator stating that the work is now done but renders no decision on whose grief is worse, the narrator's or the knight's.

Grief in Courtly Love

The poem's subject matter is couched in the medieval genre of courtly love, a French poetic tradition concerned with romantic relationships and affairs of the heart. According to the 12th-century CE scribe Andreas Capellanus, high-born ladies such as Eleanor of Aquitaine (l. c. 1122-1204 CE) and her daughter Marie de Champagne (l. 1145-1198 CE) would hold 'courts of love' in which they would discuss romantic matters, judge between couples having relationship problems, and resolve philosophical questions concerning love.

Whether these courts were serious, simple games, or a satirical invention by Andreas is still debated by scholars, but it is clear that Eleanor and Marie encouraged a literary tradition which was developed by some of the greatest French poets of their time – Chretien de Troyes (l. c. 1130-1190 CE) and Marie de France (12th century CE) among them – and that later poets, including Chaucer, drew heavily on that tradition.

Andreas codified the rules of courtly love in his De Amore (The Art of Love) which included four cardinal precepts:

- Marriage is no excuse for not loving

- One who is not jealous, cannot love

- No one can be bound by a double love

- Love is always increasing or decreasing

In addition to these, there were discussions of how one should approach, court, and win a lover as well as which conclusion to a relationship was worse: an unfaithful lover or one who died. It was decided that infidelity was worse because an unfaithful lover destroyed one's past memories as well as taking away future hope, while a lover who died was taken against their will and so one could still cherish memories of one's time with them.

This hierarchy of grief is first fully developed by the great French poet and composer Guillaume de Machaut (l. c. 1300-1377 CE) in a number of his works but most notably in his piece The Judgment of the King of Bohemia. In this poem, a lady and a knight meet by chance in a field. They are both suffering from grief and agree to tell each other their problems. The lady is grieving because her lover has died while the knight's lover was unfaithful and left him. They argue over whose grief is greater when the poet-as-narrator enters the scene to suggest they ask the King of Bohemia to decide their case. After hearing both sides, the king decides in favor of the knight because he is left with nothing but bitterness while the lady still has her fond memories.

The High Medieval Dream Vision

Chaucer's early short poems and ballads were heavily influenced by Machaut and so is The Book of the Duchess. The poem follows the form of the high medieval dream vision in which a narrator introduces a personal problem, falls asleep and experiences a dream which deals with this problem, then wakes feeling comforted as his difficulty has been resolved. Chaucer's piece adheres to the basics of this genre but departs in one significant aspect: the narrator's problem is not resolved by the dream.

One of the best-known works of the dream vision genre is the 14th-century CE poem The Pearl by an anonymous poet. The narrator is a grieving father whose daughter has recently died. Mourning his loss, the narrator wanders into a garden and, while weeping, falls asleep. He dreams that he wakes in a heavenly garden in the afterlife and meets a lovely maiden whom he recognizes as his daughter. He laments his loss, and she tells him he has lost nothing since, as he can see, she still exists, only in another place. She consoles him by citing scripture and Christian doctrine and tells him he must be patient and follow God's will and, someday, he will join her. The narrator does not want to wait and tries to cross the stream in the garden which divides them but then wakes up back in the earthly garden. He recognizes the truth of his dream and is at peace knowing his daughter is in heaven and he will see her again one day.

This work, and others like it (most notably Piers Plowman from the same era) assured the reader that all would be well if one only accepted the will of God and was patient, recognizing that God's will and plan for one's life was not always apparent and not always easy. In Chaucer's work, even though he identified himself as a committed Christian, it is not God who answers the narrator's prayer concerning sleep but Juno, a pagan goddess, and no god appears in the work to resolve the grief of either the narrator or the knight.

Chaucer's Inversion of Genres

Chaucer dismisses the central motif of the high medieval dream vision in providing no relief for his characters and also rejects the precept of courtly love concerning grief. He leaves it up to a reader to answer the question of whose grief is worse but, at the same time, subtly inverts the traditional answer that an unfaithful lover is worse. When the narrator finally understands that the knight's lady is dead, he is genuinely shocked and dismayed to a degree not seen previously in the poem. Earlier, the narrator is sympathizing with the knight and offering advice and consolation but, when he finds the knight's wife is dead, he has nothing to say except how hard that must be and how sorry he is and, shortly after, he wakes from the dream.

Andreas Capellanus claims that, if a lover is unfaithful, one should go find another and, as much as possible, should not grieve the loss. Guillaume de Machaut maintains that one should banish the unfaithful lover from one's heart and try not to ever think of them again. The narrator repeats this advice to the knight sincerely and seems to console himself when he talks about famous historical or literary figures throughout time who have thrown away their lives foolishly over unfaithful lovers (lines 721-741). The knight finally responds that none of that means anything because the lady he has lost was his whole world who gave all meaning to his life and is irreplaceable (lines 1052-1053). There is no relief for an irreplaceable loss. When the narrator realizes the knight's situation, he is struck almost speechless and, in contrast to his earlier attempts at consolation, can utter only a single line.

The hierarchy of grief according to the rules of courtly love is thereby inverted in The Book of the Duchess. It is not infidelity that brings the greatest grief because the unfaithful lover should rightly be forgotten and replaced with one better. True grief is the loss of one's love through death because one is left with all the affection one had before but no one to share it with. The knight will continue to mourn his lost love for the rest of his life because he simply has no alternative; there is no moving on when one is bound by the past through memory and throughout the poem the knight has been vividly living in the past as he tells the narrator about his true love.

Although the narrator, at the end of the poem, only says how incredible the dream was, it should be remembered that he is relating the whole experience after having the dream. The first lines of the poem in which the narrator relates his insomnia and heartache are his situation following the dream as well as before it. Unlike the typical high medieval dream vision, the narrator's problem is not resolved by the dream. Further, his glib exit at the conclusion of the poem may be his attempt to avoid rendering a verdict on whose grief was worse because he has now seen how hard it is to have lost a loved one to death and so the traditional assurances of the courtly love conceit no longer console while, at the same time, he is still suffering from his own grief which the dream vision did nothing to resolve.

The occasion of the composition of The Book of the Duchess was almost certainly a memorial service for Blanche and John of Gaunt was present when the poem was first read. Chaucer, therefore, had to make the changes in the traditions of the genres he was working in to connect fully with his audience-of-one. John of Gaunt would hardly have appreciated a work which claimed his loss was less painful than that of a cuckolded husband or lover. Although some scholars have suggested that Chaucer wrote the poem to warn John of Gaunt of the dangers of excessive grief, this is not supported by the text. The narrator's attempts to downplay the knight's grief only continue until he understands the lady is dead at which point he fully sympathizes with the enormity of the knight's loss and the poem then quickly concludes.

Unlike many of Chaucer's works, The Book of the Duchess is complete and so the conclusion must be understood as intentional and as carefully crafted as the rest of the work. Chaucer presents a reader with a study in grief from the point of view of one who is grieving but also attempting to console another. After all of the narrator's attempts, when he finally understands the knight's situation, all he can say is, in effect, "I am so sorry for your loss" and this, Chaucer suggests, is really the only thing of value anyone can say under such circumstances.