The so-called Vénus de Milo is perhaps one of the most iconic works of Western art of any period. The statue of the goddess was found on the Aegean island of Milos, to which she owes her name, on the eve of the Greek War of Independence (1821-1830 CE). With her delicate face and elegant curves, she is a vision of grace and beauty. She gazes serenely ahead, her expression peaceful, befitting a goddess. The softness of her upper body contrast with the heavy, elaborately draped garment that almost seems to slip off her hips. This enchanting figure is believed to represent Aphrodite, who in the famous story about the Trojan War was awarded the golden apple intended for the most beautiful goddess. And upon seeing this more than life-size statue in the Louvre, the viewer tends to understand Paris' decision.

She is said to be made of Parian marble (small grained metamorphosed limestone with crystalized calcium carbonate) and fashioned out of two separate blocks: the upper, nude half of her body, and her draped lower half. When the Vénus de Milo arrived at the Louvre, she was immediately praised as a masterpiece of Classical Greek art. Even though the statue later turned out to belong to the Hellenistic period, this did not diminish its popularity. Artists such as Cézanne and Dalí were inspired by her beauty and in popular culture, she assumed a life of her own.

The celebrated work of art, however, also has a shadowy side. For example, much about the discovery of the statue remains unclear due to conflicting reports about its exact findspot and the state in which it was found. The mysterious disappearance of the plinth that was originally displayed with the statue and that clearly dated to the Hellenistic period, only adds to the obscurity. It handily enabled her attribution to Praxiteles, the famous Attic sculptor of the 4th century BCE, by the director of the Louvre. In addition, the identification of the charming goddess with Aphrodite is far from certain. But perhaps the greatest enigma about this perfectly imperfect sculpture remains the question what she did with her arms. This article will deal with this question, in addition to discussing the discovery, interpretation and appropriation of the statue.

Discovery

Accounts of the discovery of the statue are riddled with misleading, conflicting, or otherwise mutually exclusive testimonies. These accounts are found in the correspondence between naval officers and commanders passing by the island, and diplomats stationed in Milos, Smyrna, Athens, and Constantinople, most notably Charles de Riffardeau, Marquis de Rivière (the French Ambassador to the Ottoman court in Constantinople) who presented the statue to King Louis XVIII (r. 1814-1824 CE), who in turn donated it to the Louvre. Some of these individuals subsequently published their testimonies, while American artist-turned-journalist William Stillman visited the island twice while some inhabitants were still alive who remembered the events surrounding the discovery.

We learn from these accounts that a peasant – by the name of Yorgos or Giorgios Kentrotas or Kendrotas and/or his father Theodoros; or Theodore Kondros Botoni; or Yorgos and his son Antonio Bottonis – discovered the statue while plowing the field or while searching for reusable building blocks in February or April 1820 CE; and that they found it on or near the peasant's plot of land, on a rocky hillside, in a small (oblong or oval) cave or cavity, in a buried or otherwise concealed chamber or niche, or among the ancient city ruins or the ancient (amphi-)theater. Other accounts describe its discovery on terraced steps covering an ancient Roman gymnasium, in the ancient city wall, in a Roman boundary-wall or in an apse of a 7th-century CE Christian church or chapel in the vicinity of the modern capital of the island (variously called Milos, Castro, or Trypiti).

The reports inconsistently claim that the statue was found with two blocks still joined together by two iron clamps or tenons; in two pieces, first the nude upper part, and after more digging the draped lower part; several other fragments of the statue (after more digging or searching: especially smaller fragments of its middle section); other statues (namely two herms) and marble fragments (including an upper arm and hand holding a round object); and that these other fragments were uncovered in the same space or near the area; that an inscribed but illegible or partially legible slab or plinth was found near the statue. Speculation about these inconsistencies seems fruitless. It should at least be clear that the truth about the exact circumstances surrounding the discovery at its findspot is irretrievably lost.

Interpretation

The fine marble statue arrived in Paris by February 1821 CE, where it has received pride of place to this day in the Louvre and came to be known worldwide as the “Vénus de Milo.” For, she was immediately identified as “Venus Victrix” (the victorious Aphrodite), hailed as a masterpiece of Classical Greek art, and attributed by the museum's director, Auguste de Forbin, to Praxiteles, the 4th-century BCE Attic sculptor who notoriously first portrayed Aphrodite nude.

The identification was based not only on the nude torso of the female figure but also on the basis of the apple that the goddess was supposed to hold in her left hand. That is to say, the indistinct round object in one of the hands found in Milos was understood to be the golden fruit of discord between Hera, Athena, and Aphrodite at the wedding of Peleus and Thetis, and that Aphrodite was eventually awarded the fruit in the Judgment of Paris. Whether this hand actually belonged to the statue has often been questioned, due to the evident differences in material, scale, and style; but examples of similar statues identified as Aphrodite with an apple in one of her hands do exist, such as the Venus of Arles.

Apart from Praxiteles, early attempts were also made to attribute the sculpture to his contemporary Scopas, Lysippus, or even Phidias, the famous 5th-century BCE creator of one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, the Zeus of Olympia. However, the Vénus de Milo was initially presented with a plinth that has often been ignored in scholarly discussions and has since disappeared. It was drawn in situ by a son of a pupil of the French painter Jacques-Louis David shortly after it was first put on display. On the (viewer's) right fragment of the plinth, an inscription read: "[Alex]ander, son of [M]enides, from [Ant]iochia on the Menander, made this [statue]."

As the Carian city (present-day Kuyucak) owed its name to the refoundation by the Seleucid king Antiochus I (r. 280-261 BCE); that would make the statue a Hellenistic provincial work, rather than Classical Attic masterpiece. Moreover, the inscription has been dated on epigraphic grounds to c. 150-50 BCE. Nearly a century after the statue's discovery, furthermore, an “Alexandros, son of Menides, from Antiochia” was epigraphically attested twice as a victor at the Thespian Festival in honor of the Museum near Mt. Helicon ( c. 80 BCE). It is inconceivable that the curators at the Louvre would have added an inscribed part to the statue if they had not believed that the (perfectly fitting) fragment did belong to the plinth. Moreover, the plinth cannot have been a modern forgery as no one could have invented a name that would later prove to be historical. Yet, not a word of the Hellenistic sculptor is mentioned in the Louvre. A Hellenistic bust (variously attributed to the river god Inopos, Alexander the Great and Mithridates VI), found on the Cycladic island of Delos may be attributed to the same artist on account of its great stylistic similarities to the Venus de Milo.

Reconstruction

After its arrival in Paris, imperfections were retouched, a proper left foot was added to the statue, and a new pedestal was fashioned without the inscribed part of the plinth. Some of the other marble fragments that were found at the same time were presented in a display case, never quite letting go of the implication that the hand with the supposed apple belonged to the figure. A great many suggestions have been made how the statue would have looked with her arms. Most of these modern reconstructions have ignored the inscribed part of the original plinth, which on the top has a square hole for attaching an object or second (smaller) figure.

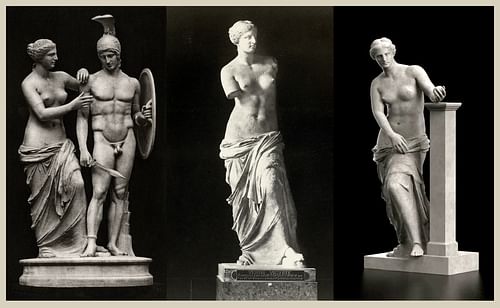

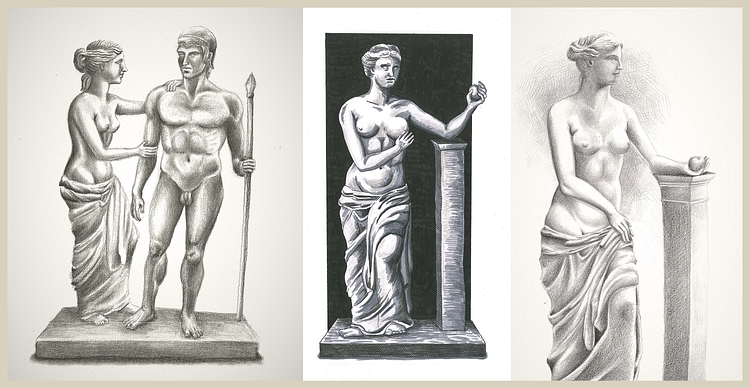

Félix Ravaisson, curator of Antiquities at the Louvre from 1870 CE until his death in 1900 CE, developed the theory that the Vénus de Milo represented the goddess of love together with the god of war, Ares (or Mars). He had full-scale casts made of the sculpture together with the Mars Borghèse to demonstrate his reconstruction. Ravaisson pointed out that in this interpretation Aphrodite would stand on the dominant (right) side of the image, with her left foot raised to further signal her superiority; and he imagined how the goddess whispered sweet words of love and peace in her lover's ear to disarm the ferocious warrior. It is true, of course, that similar group compositions, of Venus and Mars very much inspired by the types of the Vénus de Milo and Mars Borghèse, do exist from Roman Imperial times.

Another influential reconstruction was proposed by Adolf Furtwängler, director of the Glyptothek in Munich, in 1895 CE. Furtwängler did incorporate the missing part of the plinth in his suggestion and included a rectangular column on which the figure leans with her left arm, holding an apple in her hand. With her right arm across her lower torso, she grasps the drapery slipping off her body.

Many more restorations have been submitted, often with the right arms crossing the torso in some manner – as damage below her right breast indicates that some kind of support for the upper right arm was originally attached there. The swelling of the muscles of her proper left shoulder would seem to indicate that she raised her arm at least up to shoulder height. Thus, one proposal has the goddess leaning with her left elbow on a round column offering the apple to a dove placed on her right hand. In another reconstruction, she holds a mirror in her right hand, adjusting her hair with the left. In a pose similar to the Venus of Capua, the figure may be thought to write with a stylus on a shield resting on her raised left knee. Another curator at the Louvre, Charles de Clarac, saw her holding a shield in both hands, like the Winged Victory of Brescia. And yet another reconstruction interprets the statue as a Nike presenting wreaths in either hand.

It should be noted that the woman wears a headband (tainia) in her beautifully coiffed hair, not the regular crown (stephanē) of Aphrodite. This detail might be an indication that we are not looking at the goddess of love but another female figure. That she represents a divine, rather than a mortal figure, might be gauged from her unshod right foot. It has indeed been suggested that the statue represents Amphitrite, the sea goddess who was worshipped on Milos. An Algerian mosaic from Cirta depicts Amphitrite with her spouse Neptune (Poseidon), in a nearly identical pose as that submitted by Ravaisson.

One more proposed reconstruction deserves mention, offered in 1960 CE by Elmer Suhr, professor of classics at the University of Rochester. He imagined the goddess in the act of spinning, with her left arm raised up high and holding a distaff in the hand, while the right arm extends forward turning the spindle. Although this interpretation takes the statue's anatomy into account, including the musculature of the left shoulder and the twisting torso (with its apparent spinal deformity), it does not incorporate the inscribed part of the plinth or the possible object standing to the (viewer's) right. Still, an upraised marble arm carrying a (perhaps golden) distaff, due to its weight and fragility, might well have required a support (not envisioned by Suhr) – for instance a column or a companion such as Eros or a statuette of herself such as on the Venus of Lovatelli. Maybe one the of Fates (or Moirai) might be thought more appropriate for spinning threads, but Suhr has demonstrated that spinning did have associations with fertility, sexuality, and marriage – and referred to parallels such as the Venus of Castellani.

Appropriation

With its long-held insistence that the Vénus de Milo represents a masterpiece of Classical Attic art from the school of Praxiteles, Scopas, Lysippus or Phidias, rather than a late-Hellenistic work by a then-unknown sculptor, Alexander of Antiochia, the Louvre succeeded in promoting the statue to one of its most cherished treasures. In 1911 CE, Auguste Rodin, the famous French sculptor, wrote an ode to Vénus de Milo in which he praised the ancient statue for its harmonious proportions, its perfection of divine grace, universal beauty, and noble truth. In all, Rodin saw the immortal personification of Womanhood itself.

The iconic ancient sculpture has become an inspiration for many other modern artists since its arrival in the Louvre. The French Post-Impressionist painter Paul Cézanne, for instance, drew a pencil study (c. 1881/8 CE). René Magritte, the Belgian Surrealist, painted a reduced-sized plaster cast in bright pink and dark blue, which he entitled “Les Menottes de Cuivre (The Copper Handcuffs)” (1931). Neo-Dada Pop Artist Jim Dine has regularly revisited the Vénus de Milo in his paintings and sculptures since the 1970s CE and has placed three larger-than-life-sized, headless bronzes in 1990 CE near the MoMA on Sixth Avenue in Midtown Manhattan, N.Y., appropriately called “Looking Toward the Avenue.” American visual artist Lawrence Argent reimagined a 28-meters (92 ft) silver swirling Venus for Trinity Place in San Francisco, CA, shortly before his death (2017 CE).

Her image has graced covers of magazines and advertisements; replicas can be found in souvenir shops; songs have been performed about her by Nat King Cole, Miles Davis, Louis Armstrong, and Chuck Berry; her image appears on coffee mugs and rubber toys that squeak; she even appears as a gummy in an episode of The Simpsons.

Perhaps the most well-known and certainly most fascinating appropriation is the “Vénus de Milo aux tiroirs (Venus of Milos with Drawers)” by Spanish Surrealist Salvador Dalí (1936 CE), a half-size painted plaster cast with metal knobs and fur-tuft pompons on its slightly opened drawers. Inspired by Marcel Duchamp's “ready-mades” and heavily influenced by Sigmund Freud, Dalí's reimagined reproduction purports to exhibit the ancient goddess of love as a fetishistic anthropomorphic cabinet with secret drawers filled with a maelstrom of mysteries of sexual desires that only a modern psychoanalyst can interpret.

Conclusion

From its obscure discovery via deceptive interpretations and various attempts at reconstruction to fanciful appropriations, the so-called Vénus de Milo continues to fascinate. Her physical beauty and aesthetic charm have the disarming effect of encouraging flights of fancy. Without her arms, her mystery is all the greater, the statue has come to embody the ideal female form and has thus become the object of more than an occasional sexualized gaze.