Elephants were thought of as fierce and frightful monsters in antiquity, very real though rarely seen until the Hellenistic period. They were deployed on the battlefield to strike terror into the enemy, however, since fear was considered divinely inspired, elephants can be interpreted as religious symbols even in warfare. From the reign of Alexander the Great elephants became associated with Hellenistic military processions and coinage often expressed the symbolic connection between elephants and military victories.

“Behold the wild beasts around you,” God spoke to Job and continued describing a fearsome and mighty monster, literally a Behemoth (lit. “wild beast”), likened to bulls, with ribs made of bronze and a spine of cast iron. (Job 40:15-24.) This beast lies by the papyrus, reed and sedge, it strikes the river to pour water in its mouth and does not fear the flood. Regardless of what animal the biblical Behemoth might reflect, it remains interesting that later, according to Pliny, the Romans would call elephants “bulls” after first encountering them during the campaign against Pyrrhus. The first classical author to write about elephants, Herodotus, mentioned them among various more or less fabulous creatures and wild beasts, such as lions, bears, snakes, serpents, unicorns, dog-headed men, headless men, and savages.

Later in the 5th century BCE, Ctesias, who (unlike Herodotus) must have seen elephants himself, declared that Indians hunt the man-eating martichora (elsewhere called manticore) on elephants a paragraph before discussing griffons that protect the goldmines in the Indian mountains. Next, the venerable Aristotle likewise discussed elephants in the same context as the martichora and believed that they could live for up to 300 years and “can be taught to kneel in the presence of the king.” (History of Animals 2.1, 8.9 and 9.46.)

Greek authors continued to associate elephants with legends and fabulous monsters – that is, for our modern mind non-existing figments of ancient imagination. Diodorus related that Indian elephants were outfitted to strike terror in warfare against the invading Assyrian queen Semiramis. Strabo mentioned elephants about 50 times: citing Onesicritus that elephants could live for up to 500 years; Megasthenes who claimed to have seen elephants in a Bacchic chase; and Artemidorus who described elephants in Ethiopia along with sphinxes and dragons. Even later authors could be quoted to confirm that in classical Greek and Latin literature, elephants belong to the same order of fierce and frightful fabulous monsters as the martichora, unicorn, griffon, sphinx, dragon, and hippocamp.

From Alexander to Hannibal

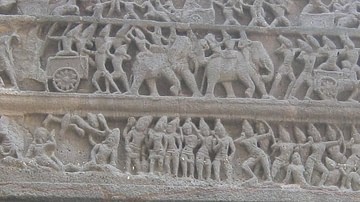

During the eastern campaign of Alexander the Great (356-323 BCE), Greek and Macedonian soldiers first encountered elephants in Assyria, at the Battle of Gaugamela (331 BCE), where they were, however, apparently not deployed. The use of elephants in warfare had spread to Persia in earlier centuries from India where elephants had been used for millennia. After Gaugamela, 15 elephants were captured from the Persian camp, along with the baggage, chariots and camels. As the gates of Susa were opened for Alexander, his forces acquired another twelve elephants.

Farther along the campaign, another 125-150 elephants were obtained in the Indus Valley as a gift of a local prince and through hunting. The Macedonian army then encountered elephants in the field at the Battle of the Hydaspes (326 BCE; the westernmost tributary of the Indus now called the Jhelum) against a king called Porus (perhaps Paurava, i.e., “King of the Purus”). During the ensuing fight, the enemy's elephants trampled foot soldiers indiscriminately in the confusion when attacked from the flank by the Macedonian cavalry. Another 80 elephants were captured after the battle, thus bringing the total to about 250.

The Macedonian army, nevertheless, refrained from advancing into the Ganges Valley – as they received information not only about the vastness of the country but also the alleged strength of its forces (including at least 3000 elephants). Upon their return to Persia (c. 325 BCE), some 200 elephants are mentioned which had arrived via Arachosia and Carmania. When Alexander died, his funeral carriage was decorated among many other things with a tablet of Indian elephants driven by mahouts, followed by Macedonian troops.

During the succession crisis that erupted at Alexander's sudden death, elephants were employed not only when opposing factions were about to engage each other in fighting, but also to execute the death sentence after the rivals were put on ad-hoc trial. When Ptolemy (c. 367-282 BCE), the appointed governor of Egypt, transferred said funerary cortege to Memphis, the Macedonian regent Perdiccas retaliated by invading Egypt with the royal army, including elephants (c. 321/0 BCE). After Perdiccas' disastrous defeat about 50-60 elephants apparently fell to Ptolemy. The latter minted coinage that expressed the symbolic connection between elephants and Alexander's military victories.

His son, Ptolemy Ceraunus, who was passed over for the succession, imitated his father's coinage when he claimed the succession over Lysimachus' kingship. For, after the latter's death at the Battle of Corupedium (280 BCE), Ceraunus had first joined Seleucus, then murdered him as avenger of Lysimachus' death, and issued gold staters with the portrait of Alexander on the obverse and Athena Nikephorus on the reverse along with smaller symbols such as an elephant and a lion's head. Ceraunus famously died on the back of an elephant against the Galatians entering the Greek peninsula from across the Balkans (279 BCE).

When Pyrrhus of Epirus (319-272 BCE) requested support for his upcoming Italian campaign, Ptolemy II could afford to provide him with 50 elephants, among other forces. Pyrrhus already had 20 war elephants (although it remains unclear from where or whom he had obtained them). The ultimately unsuccessful campaign was commemorated on a ceramic plate from Capena (now in the Villa Giulia, Rome), which shows a turreted elephant with a rider and fighters on its back, followed by a cub. It was the first time that the inhabitants of the Italian peninsula had ever seen elephants.

The Pyrrhic campaign inspired the Carthaginians to acquire war elephants by the time of the Second Punic War (218-201 BCE). When Hannibal (247 - c. 182 BCE) moved against Rome, he crossed the Pyrenees from Spain with 37 elephants among his vast forces. Although the Carthaginians suffered heavy losses while crossing the Alps, an unspecified number of elephants did enter the Po Valley and then crushingly defeated the Roman consular armies at the Trebia River. While reinforcements of African forest elephants would eventually reach Hannibal, they failed to assert any decisive effect even at the final Battle of Zama (201 BCE). Still, their symbolic importance for Carthage is expressed on a series of Hannibal's coinage, which depict a cloaked rider with a goad in his hand, but no turret.

From Rome back to India

Allegedly the cognomen of Gaius Julius Caesar (100-44 BCE) derived from the Moorish word for “elephant” (caesai), rather than from caesius or caeruleus (pertaining to the color of the sky). (Hist. Aug., Ael. 2.3.) Furthermore, Caesar supposedly entered Britain with an elephant in 54 BCE (Polyaen. 8.23.5.) More historically, Juba of Numidia (approx. present-day northern Algeria) supplied elephants to the Pompeian forces during the Roman Civil War (49-45 BCE). Still, Caesar was able to defeat Metellus Scipio at the Battle of Thapsus in Tunisia (46 BCE) and he captured over 60 elephants after his African victory and displayed 40 in a Roman triumph. Indeed, Caesar's silver denarius coinage of his moving mint (c. 50-45 BCE) significantly employed the elephant trampling a serpent as he crossed the Rubicon River as an allusion to the victory of good over evil.

One of the most precious artifacts among the Boscoreale treasure discovered in 1895 CE (now in the Louvre) – and perhaps one of the most beautiful works of ancient art – is a silver emblema dish with an allegorical portrait attributed to Cleopatra Selene (40-5 BCE), the daughter of Cleopatra and Mark Antony. After the death of her parents, Octavian brought her to Rome and subsequently married her to King Juba II of Numidia, son of Juba I. They were established as rulers of Mauretania (approx. present-day northern Morocco) and their son Ptolemy was the last known descendant of the Ptolemaic dynasty. On the emblema, Cleopatra Selene wears an elephant scalp as a headdress and is surrounded by a profusion of religious symbols and attributes particularly associated with Ptolemaic Egypt.

Let us briefly return to the Hellenistic period and quickly make our way back eastwards. Most war elephants deployed in the Hellenistic period derived from India. Seleucus I (c. 358-281 BCE) is said to have obtained 400-500 which he employed against Antigonus I and Lysimachus but then they are never heard of again. Antiochus I (324/3-261 BCE) deployed war elephants against the Galatians who had crossed the Balkans into Greece and then moved into Asia Minor (c. 275/4 BCE). Allegedly, Antiochus' 16 elephants instilled panic among the Galatians, causing great carnage and producing victory in battle. Seleucid coinage regularly propagates the symbolic military importance of elephants as an expression of their power. Incidentally, Eleazar Maccabaeus was crushed by a Seleucid elephant, after piercing it with his spear at the Battle of Beth Zechariah in 162 BCE. (1-Macc. 6:34.)

On many Hellenistic-style coins, signet rings and seal stones from Graeco-Bactria and Graeco-India elephants are depicted – a tradition that dates back to Harappan stamps-seals from the 3rd and 2nd millennium BCE. The iconography includes Bactrian kings wearing the elephant scalp as headdress as well as Hindu deities accompanied by an elephant. The founder of the Mauryan kingdom, Chandragupta established his power shortly after Alexander's death (r. c. 322/1-299/8 BCE). He issued punch-marked silver coins with religious symbols featuring an elephant and a bull, the sun and a tree on a hill, as well as the chakra (a “disc” referring to a Tantric nerve nexus). Well into common era the elephant continued to feature frequently on Kushan coinage (1st-4th century CE), including kings riding elephants.

Elephants as Religious Symbols

Elephants were historically deployed on the battlefield to strike terror into enemy troops inexperienced with their sight. Cavalry horses, especially, are frightened even of their smell. However, the animals often turn on their own ranks trampling indiscriminately whoever comes in their way. One should wonder, therefore, why generals would be interested in recruiting these pachyderm monsters in warfare at all when there is little strategic advantage in deploying them against each other. We may take as a clue from the ancient notion that fear, like panic, was divinely inspired, and that elephants should first of all be interpreted as religious symbols – even in warfare.

This suggestion is substantiated by the accounts of the Battle of Raphia (217 BCE) which decisively settled the Fourth Syrian War between the forces of Ptolemy IV and Antiochus III in favor of the former. The encounter was one of the largest pitch battles of the Hellenistic period, and supposedly the only ancient battle in which African elephants fought Indian. Before the fighting, Ptolemy's elephants are said to have raised trunks in prayer to the rising sun. The king commemorated his victory by sacrificing four of his enemy's elephants. When the sun god Helius (Amun-Ra) appeared to him in a dream expressing his anger, Ptolemy set up four bronze elephants as votives to appease the god.

There are, furthermore, evident religious connections and influences between elephants and Hindu deities. For instance, Indra, the Lord of Heaven, rides a white elephant, which symbolizes his victory over the dragon Vritra, his adversary. Incidentally, Indra, like Zeus and even Alexander the Great, wields the thunderbolt. The frightful emanation of Shiva Bhairava and the mother goddess Varahi are depicted seated on an elephant; he clad in elephant's skin and tiger's hide, with a drum, corpse, trident, bowl, stick, and deer in his six hands; she with a plough, sacred tree, elephant goad, and noose. The Indian elephant god Ganesha, the Lord of Hosts, belongs to the retinue of Shiva. While the worship and iconography of Ganesha only developed from the 4th century CE, the sacred status of the elephant in India is well established since the 3rd millennium BCE.

Alexander's Divine Sonship

Alexander's elephant headdress is generally understood as an emblem of his victory over Porus. It appears frequently as an attribute of military might on Hellenistic bronze figurines and decorative elements (of which several examples are found in museums across the world). One such small-scale statuette (now in New York), perhaps based on large-scale sculpture, depicts Alexander in the act of combat, riding a (now missing) animal, wearing the elephant scalp on his head.

Alexander's posthumous portraiture was first devised under Ptolemy in Egypt and subsequently imitated by Lysimachus, Seleucus, and Ceraunus. Alexander's facial features are full of pathos, his diadēma (headband) signifies his royalty, his large bulging eyes intimating his divinity. The portraiture is best-known from early Hellenistic coinage but also appears on engraved gems. Of particular importance is the combination of the elephant scalp with a ram's horn over his temple and the aegis (a sacred goat's fleece) thrown over his shoulder. The combination of these three attributes remains poorly understood, although the portrait as a whole makes little sense from a classical Graeco-Macedonian perspective.

Starting with the association with Alexander's Indian triumph, the exuvia (elephant's scalp) might best be understood as an attribute of an Indian deity, such as Indra, Shiva, or Krishna. Notice particularly the protuberance on the elephant's forehead which is particular to the Indian elephant. The trunk appears to curl as if in prayer in a manner resembling an upright cobra (uraeus). Furthermore, the scalp is worn over the head as Heracles wore the scalp of the Nemean Lion. That is to say, the headdress represents the heroic appropriation of a monstrous attribute as an emblem of victory over a fabled foe.

Alexander was believed to be descended from Heracles, the son of Zeus. Ancient authors recognized Heracles in an unspecified Hindu deity and the identification remains unsettled among modern scholars. Indra, the sky god, who wields thunder and lightning, might be compared with Zeus. Indra, however, is the son of Dyaus Pitrā (“Sky Father”), which parallels Zeus Pater and Jupiter. The supreme deity Shiva is considered both benign and frightful. The frightful Shiva, also understood as an emanation of Indra, is a destroyer, the slayer of demons. He, therefore, embodies aspects of both Heracles and Dionysus, and Alexander was also believed to be descended from Dionysus, through Deianira, the wife of Heracles. Krishna, an avatar of Vishnu, is a princely hero. So, he too may possibly have been the Hindu deity identified with Heracles by the Greeks and Macedonians.

Next, the ram's horn that encircles Alexander's temple is understood to be an attribute of Ammon, the Libyan oracular deity, whose cult lies in the desert oasis of Siwah. Ammon was identified both with Zeus and Amun-Ra, the supreme creator god. After his coronation in Memphis, the priest at Siwah confirmed that Alexander was recognized as the son of god.

The third attribute, the aegis belonged to Zeus, who presented it to Athena, who in turn is commonly depicted wearing the fleece. In Alexander's posthumous portraiture, it seems to be tied around his neck by two writhing snakes. The snakes might allude to the legend that Olympias was impregnated by a god in the form of a snake. The snakes may also refer to the uraeus (upright cobra) or the serpents coiling around the head of Medusa.

The three attributes were associated with three supreme deities of three different cultures: the aegis with Zeus; the ram's horns with Ammon; the exuvia with Indra. All three attributes symbolize Alexander's divine sonship and the attributes portray him as the heroic descendant of the slayer of demons, underlying the associations between the mythic figures of Dionysus and Heracles (both sons of Zeus), Shiva (an emanation of Indra) and Krishna (an avatar of Vishnu), as well as Horus (the reincarnation of Osiris). In other words, Alexander's posthumous portraiture presents him as the rightful ruler over these cultures and the known world.

Triumph of Fame over Death

One of Petrarch's four famous Triumphs, the “Triumph of Fame over Death,” has been frequently illustrated by generations of artists. On an early 16th-century Flemish tapestry (now in New York) the personification of Fame stands in a chariot drawn by two white elephants as they trample death and fate. Fame is accompanied by Plato and Aristotle, Alexander, and Charlemagne. The shape of the elephants' trunks resembles the trumpet Fame sounds. Alexander's undying fame thus owes more than is usually acknowledged to the elephant.

Understood as an emblem of military might, in antiquity and well beyond, I have argued that the elephant was a mythic monster. Employed historically in warfare to strike fear in the enemy, it should be remembered that panic was believed to be divinely inspired. The religious association of the elephant with victory and power is therefore obvious. This association might be compared with the aegis, which served the apotropaic function of warding off evil forces and was itself connected with divine protection and military defense. Even the ram's horn – derived from the god Ammon of Siwah, and Amun-Ra of Memphis – acts to instill terror. In Greek mythology, Pan and the satyrs in the retinue of Dionysus were depicted with ram's horns. The ram's horn was thus a divine attribute associated with panic and madness. In short, in ancient thought elephants were considered mythic monsters that belonged to the same category as fabulous beasts such as the griffon and sphinx, martichora and unicorn, dragon and hippocamp, very real though rarely seen until the Hellenistic period.