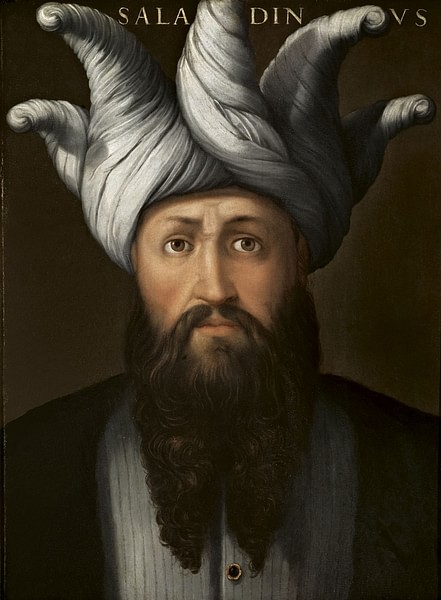

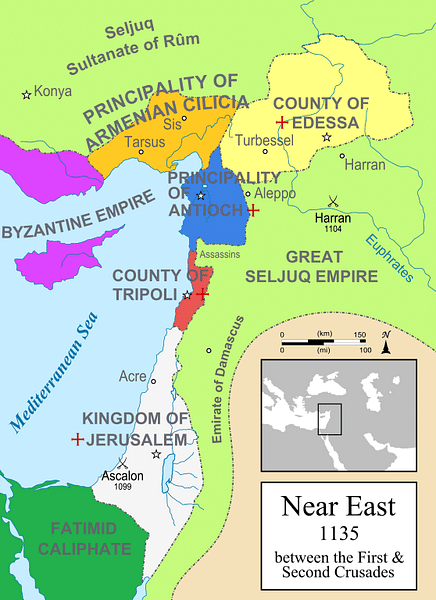

Saladin (c. 1137 – 1193 CE), the Muslim ruler who crushed the mighty Crusader army at the Horns of Hattin (1187 CE) and re-took Jerusalem after 88 years of Crusader control, was born in a world where the disunity of the Muslims had allowed foreign invaders to take over their territory. The Islamic front was divided between the Sunni Abbasid caliphate of Baghdad and the Shia Fatimid caliphate of Egypt. Apart from this, the once mighty Seljuk Sultanate (which acted as the supreme authority over the Abbasids), was now fragmented into small states; each ruled by a separate leader. The stage was set for foreign occupation, and by the end of the First Crusade (1095 – 1102 CE), Jerusalem, a holy city for Jews, Christians and Muslims, had fallen into western hands. The local population was brutally massacred and to add injury to insult, the Al Aqsa Mosque was desecrated. Unchallenged by the disunited Muslims, the occupying Europeans, or Franks as they were known, established four Latin kingdoms, collectively referred to as the Crusader States: the County of Edessa, County of Tripoli, Principality of Antioch and the Kingdom of Jerusalem.

Slowly and steadily, the “Saracens” (the term used by the Franks to refer to the Muslims) were preparing to strike back under the leadership of a ruthless leader – Imad ad-Din Zengi, the “atabeg” (regional representative of the Seljuk Sultan) of the Mesopotamian city of Mosul. After bringing Aleppo under his control, Zengi dealt the first major blow to the Europeans by retaking Edessa in 1144 CE. But he was murdered two years later and his mission to drive out the Franks passed on to his younger son Nur ad-Din (sometimes also given as Nur al-Din), his successor in Aleppo. Saladin's family worked for the Zengids at the time, his uncle Asad ad Din Shirkuh was one of Nur ad-Din's bravest generals. Nur ad-Din was like a master to Saladin and in time (after his death in 1174 CE), it would be Saladin and not Nur ad-Din's own relatives and descendants, who would carry on his mission. Harold Lamb, writes in his book, The Flame of Islam: “Undoubtedly, he was the man most fit to succeed Nur ad-Din.” (38)

The first and foremost part of that mission would be to unite the Muslims under one banner: Jihad (literal meaning – struggle, contextually – holy war) by any means necessary.

Vizier of Egypt

Saladin rose to prominence in 1169 CE when he was chosen as the vizier of Egypt by the Fatimid Caliph Al Adid after his uncle Shikuh's death, who was the former vizier (he had earned the rank after a six years long struggle along with Saladin, as his second in command, to push the Crusaders out of Egypt and to extend Zengid authority over it). All odds were against this young and inexperienced Sunni Kurd, who was a complete alien to the Shia dominant Egypt. But Saladin proved everyone wrong; he was quick to appoint his own family members to important positions in Egypt as they were the only ones in the hostile kingdom of Nile whom he could trust. And as for all those who stood in his way or threatened him, let us just say that they all “moved aside” under mysterious circumstances and with striking regularity. Stanley Lane Poole describes Saladin's motives as follows:

He devoted all his energies henceforth to one great object – to found a Moslem empire strong enough to drive the infidels out of the land (referring to the Latin Kingdoms or the Outremer). “When God gave me the land of Egypt,” said he, “I was sure that He meant Palestine for me also.”… He had vowed himself to the Holy War. (99)

Saladin did not wait a moment to expand his domain from his Egyptian power-base:

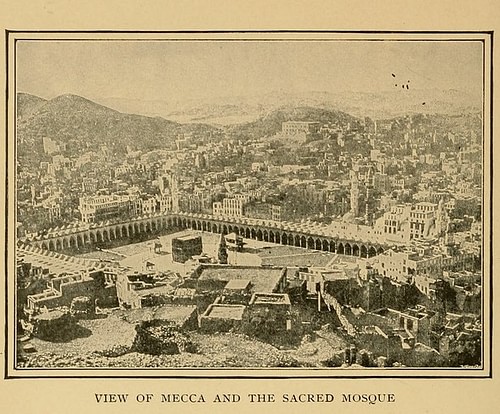

- 1170 CE: In December, Saladin captured the fort of Eilat at the head of the Gulf of Akaba, hence securing the Red Sea route for pilgrims to Mecca (the most important holy city of Islam).

- 1171 CE: On Nur ad-Din's orders and the insistence of his own father, he abolished the Fatimid Shia Caliphate and brought Egypt back under the canopy of the Sunni Abbasid Caliphate. The caliph Al Adid never came to know of this act as he was ill and Saladin wanted to let him die in peace, which he did a few days later. Now Saladin had absolute control over Egypt.

- 1172 CE: Saladin sent one of his generals to conquer the provinces on the North African coast, Barka and Tripoli (not to be confused with the Crusader County of Tripoli in modern-day Lebanon), as far as Gabes, which he did by the next year. Although he could not really consolidate his power beyond the province of Barka.

- 1173 CE: He sent his brother Turan Shah to conquer Sudan with a two-fold motive: expansion of power and suppression of Black rebels who were threatening to join the Crusaders. Shah managed to achieve both motives when he conquered the Sudanese city of Ibrim.

- 1174 CE: Turan Shah then led an expedition to Mecca, where he was joined by a powerful Arab lord, to conquer Yemen. One after the other, Yemen strongholds such as Zebid, Jened, Aden, Sana, etc. fell to the Ayyubids. This expedition also gave the Sultan, free access to the Red Sea trade routes, which he used to further empower his Egyptian power-base.

Taking Syria

Nur ad-Din died in 1174 CE and was succeeded by his eleven-year-old son As-Salih but as he was a minor, a eunuch named Gumushtigin became his regent and moved him to Aleppo. The governor of Damascus, threatened by both Gumushtigin and the King of Jerusalem: Amalric I (who had advanced on Syria to exploit Nur ad-Din's death), turned to Saif ad-Din II (the ruler of Mosul and grandson of Imad ad-Din Zengi) for help but he was uninterested and busy annexing Nur ad-Din's territories. He then pleaded to Saladin for help - the latter had not been willing to annex Syria unless it was for Islam and now it was. Syria was without a leader and vulnerable to Crusader attacks and even more to the greedy personal ambitions of people like Gumushtigin. Saladin left Egypt with 700 hand-picked horsemen and took control of Damascus (which would become his capital), where he received much applause for distributing a fortune from As-Salih's treasury among the people. Stanley Lane Poole describes Saladin's initial reluctance to march on Syria as follows:

Mere personal ambition would have led most men in Saladin's position to take advantage of the weakness of his neighbors, but to ascribe any such conscious motive to him would be to misread his character. Unless he could persuade himself that the general interests of the Saracens, and especially of the Moslem faith, required his intervention, he would hesitate to aggrandize his power at the expense of one whose (referring to As-Salih) sister was his own wife and whose father had been his lord and benefactor. (134)

Saladin left his brother Tughtigin in Damascus as governor and left to conquer the Syrian cities of Emesa and Hamah, then he turned to Aleppo which shut its gates on his face. The vizier allied with an order named “Hashishins” (the Assassins) and demanded that the Sultan be killed but as fate was his best friend, he escaped death at the hands of the order, which was known to never miss its target. Then came the news that Raymond, the Count of Tripoli (the Latin Kingdom) had attacked Emesa (on the request of the vizier, as a diversion) and Saladin rushed there in response but the Crusaders withdrew before he arrived. Saladin then conquered Baalbek, where his own father was once a governor under Imad ad Din Zengi.

Saladin then marched onto territories neighboring Aleppo and conquered them including the vital fort of Azaz, after a dangerous siege. In 1176 CE, a treaty was signed between Saladin and As-Salih and the latter recognized the former's over-lordship. As-Salih's sister came to Saladin to plead for the return of Azaz, the Sultan not only complied to her request but also escorted her back to the gates of Aleppo with numerous gifts (it is noteworthy that Saladin almost lost his life while he was besieging Azaz, this shows his generosity and his devotion to the family of Nur ad-Din). Saladin also allied with the Assassins after realizing that destroying them was extremely risky but an alliance was mutually beneficial. He left Turan Shah in charge of Syria and returned to Cairo, where he supervised the development of its infrastructure, especially its citadel.

Race For Aleppo

First Saif ad Din and then As-Salih died in the year 1181 CE. Saif ad Din's brother Izz ad-Din succeeded him in Mosul and had his brother Imad ad-Din (named after his grandfather) placed in charge of Aleppo. Imad ad-Din was originally the governor of the Mesopotamian city of Sinjar and was not liked by the people of Aleppo, in fact on one occasion, the people of Aleppo paraded a wash-tub before him, saying: “You were never meant for a king! Try taking in washing!” (Poole, 173).

Syria was once again vulnerable and had to be brought to order. Saladin marched upon the Jezira region of Northern Mesopotamia in 1182 CE where he conquered city after city including Edessa. Then he turned towards Sinjar and besieged it for 15 days after which it fell. Upon the fall of the city, in December, Saladin's army lost all control, they stormed and sacked the city, but he managed to save the governor and his officers and had them sent to Mosul in a safe and honorable manner. Now Saladin turned towards Aleppo, neither side was willing for a battle (although Saladin could have crushed Imad ad-Din, he seems not to have wanted to) and an exchange was arranged: Aleppo in return of Sinjar and its dependent territories (on vassal terms). Imad ad-Din happily complied and in 1183 CE Saldin entered the city.

Defending Mecca & Medina

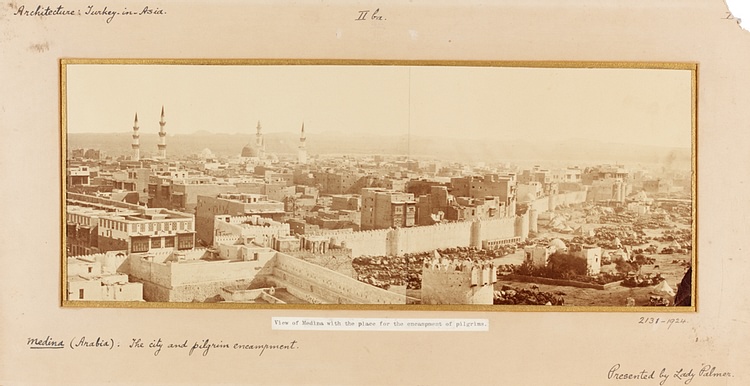

After gaining Aleppo, Saladin became the most powerful figure in the Islamic world. To the horror of the Crusaders, he had managed to unite all major Islamic states surrounding the Latin kingdoms under his banner. In 1183 CE however, a Crusader named Reynauld of Chatillon dared to send a fleet through the Red Sea route to attack the Muslim holy cities of Mecca and Medina (with the intent of destroying the Ka'aba and desecrating the grave of the Holy Prophet of Islam – peace be upon him) but this fleet was stopped in time by the Ayyubid ships from Egypt and the Crusader soldiers were captured and killed like cattle for blasphemy.

John Davenport writes about Saladin's reaction:

So uncharacteristic was such retribution that his commanders did not follow through on Saladin's order at first. The Sultan's own brother, Saif al-Din al-Adil, questioned his decision, prompting Saladin to write him an explanatory letter. The men must die, Saladin wrote, for two reasons, one practical and one personal. First, the raiders had almost made it all the way into one of the holiest cities in Islam undetected. If he let them live, they would certainly return by the same route with a larger, more determined force… Second, the honor of Islam cried out for revenge, for blood. (46)

Saladin was angered at this move and in return, he twice besieged Reynauld's stronghold – the impregnable fort of Kerak but had to withdraw both times as the forces of the Kingdom of Jerusalem came to Reynauld's aid. In 1185 CE, the King of Jerusalem, Baldwin IV the leper (son and successor of Amalric I) died and peace was declared between the Franks and the Muslims as the Crusaders were in no state to wage any holy wars.

Unified Islamic Front & Jihad

Mosul, the only thorn in Saladin's path, also entered the canopy of his over-lordship in 1186 CE when Izz ad-Din offered to be Saladin's vassal. The Sultan agreed and Izz ad-Din was allowed to keep and govern his lands. At this point, Saladin overpowered the Crusaders and angering him or attempting to break the peace would now have been the worst idea. However, that is exactly what Reynauld did in 1187 CE when he attacked a Muslim trade caravan in defiance of the treaty. The Kingdom of Jerusalem backed him up in this outrageous act and paid the price when Saladin annihilated the greatest ever Crusader army (until that time but still smaller than Saladin's army) in the Horns of Hattin in July, 1187 CE, where he also fulfilled his oath of killing Reynauld with his own hands.

This great victory which paved the path for the blood-less re-taking of Jerusalem (although many Christians would be enslaved) later the same year was only achieved because of Saladin's 17 long years of effort to unite the Islamic states under his effective leadership. Later on in his life, when he was forced to defend his gains against the Third Crusade, despite being old, weak and seriously ill, he commented about this fragile unity: “If I were to die, it would be difficult to get together such an army as this again.” (Lamb, 166). And considering subsequent events, he was proved absolutely right.

This content is provided by the

This content is provided by the