Dogs have played a prominent role in the lives of humans going back thousands of years and, more than any other domesticated animal, this role has remained relatively unchanged. In the present day, dogs serve as guardians, perform tricks or tasks, and are seen as companions and even members of one's family just as they were in earlier eras.

Although in the past dogs were more often working animals than pets, the dog was still valued highly and, during medieval times, was considered an important status symbol, vital to the hunt, and was often prominently featured in one of the most popular forms of medieval literature: courtly love romances.

In Europe in the Middle Ages (476-1500 CE), the dog performed many services such as turn-spit (turning the kitchen spit), guard dog, lymer (a dog that sniffs out game), a raches (one that ran the quarry down once the hunt was on), kennets (smaller hunting hounds), water-drawers (dogs who turned the well-wheels to raise buckets), and messengers (dogs who carried letters tucked into their collars back and forth between homes or businesses). Primarily, however, the dog was associated with the hunt and breeders focused on methods of creating the best hunting dog which would bring the greatest price. Hunting dogs wore different kinds of collars from a broad leather piece to slim cords depending on their role in the hunt and their breed.

Dogs & the Hunt

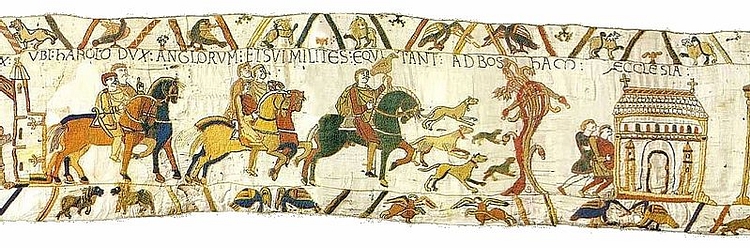

The most famous depiction of collared dogs at the hunt in the medieval era is probably the Bayeux Tapestry which records the victory of William the Conqueror (l. c. 1027-1087 CE) at the Battle of Hastings in 1066 CE over the king of England, Harold Godwinson (also known as Harold II, r. January-October 1066 CE). The tapestry (which should more accurately be designated an embroidery) is thought to have been commissioned by Bishop Odo, William's half-brother, sometime in the 1070s CE and features a number of dogs.

Dogs in the piece wear slim collars most likely made of leather. The collars have a ring for the leash and are of different colors as the dogs run free as though on a hunt, in the company of their master, Harold, even though no quarry is specified in the embroidery. Scholars have speculated that this image was composed to illustrate Harold's carelessness as opposed to William's steady determination.

Europe had enacted collar and leash laws as early as c. 515 CE in the Lex Romana Burgundionum. This regulation stipulates that dogs must be restrained by collars and leashes and that any damage done by an untethered dog would be the full responsibility of the owner. This did not apply to the king or nobility, however, and the Forest Laws of the 6th century CE (the first game laws) forbade hunting in the king's forest while allowing for the hunting parties of nobility to cross any land they pleased.

The dog most commonly used in these hunts was the greyhound, and the Forest Laws, in conjunction with the popularity of the hunt among the nobility, resulted in the legislation of King Hywel Dda of Wales (c. 880-950 CE) which made killing a greyhound a capital crime. This was quite possibly in response to the rampant course of the hunt over other people's property without regard for their dogs, crops, or homes (a practice which would continue for centuries in Britain) and possibly reprisals against dogs by landowners. King Canute (c. 985-1035 CE) made it illegal for anyone but nobility to own a greyhound and increased the severity of the Forest Laws. He mandated the hobbling of other dog breeds (by severing the tendons) within a ten-mile radius of the king's forest, a practice which was continued by William the Conqueror.

All of these laws were thought, by the nobility at least, to be in the best interest of the crown and, since the king was elevated by divine right, in the interests of the people generally. By c. 1070 CE, these laws were well established and this leads to the interpretation of King Harold's dogs running without a defined purpose in the Bayeux Tapestry as alluding to his carelessness and failure to rule effectively. Although an interesting interpretation of the piece, it seems just as likely the hounds have just been released for the hunt and no quarry yet found. The claim that the dogs in the beginning of the story are depicted differently from those at the end is untenable; the dogs throughout the embroidery all are shown in more or less the same way.

Dog Collars of the Hunt

These collars the dogs wear in the piece could have been similar to those discovered in boat graves in Valsgarde, Sweden, the leather bands with four-pronged metal squares sewn onto them, attached by a loop and twine around the dog's neck. Dog collars in the medieval period ran the spectrum from the simple leather band to elaborate metal work. A collar from Waterford, Ireland dated to the 12th century CE is an intricate bronze web pattern which was attached to a leather backing by six small holes drilled into it. This collar is also thought to be similar to those worn by the dogs in the latter section of the Bayeux Tapestry.

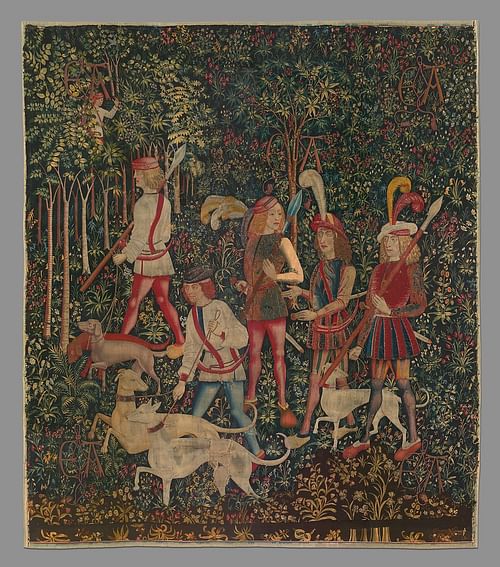

Paintings from this era depict collared dogs on the hunt guided by long poles, not leashes. A variation on the pole motif is most famously seen in the Unicorn Tapestries, created c. 1495-1505 CE, which are seven elaborate works depicting a medieval hunt for the unicorn in which the hunters wield spears instead of poles. Dogs feature in six of these seven tapestries, all in broad collars which are inscribed with letters and floral designs. The dog collars have been variously interpreted as either representing the owners, the dogs, or as a kind of metafictional device indicating the family the pieces were created for.

The dogs of the Unicorn Tapestries are mostly greyhounds, though other breeds are also featured, and are shown in the broad leather collar. Some dogs, however, are restrained by what appear to be slip leads, slim chains, or ropes attached to the collar. It is clear the dogs are integral to the hunt and it is thought the action of the seven works realistically depicts the role dogs played in actual hunts of the time. Dogs were primarily used as shepherds, in hunting, and as guardians of the home and livestock in this era, just as they had been in ancient Rome and Greece.

The tapestries follow the initial hunt for the mythical unicorn to its cornering by the hounds and its final capture in the last tapestry, in which no dogs appear. Although the tapestries have, for centuries, been interpreted through a Christian lens - with Christ represented by the unicorn - this makes very little sense when one views the scenes themselves. Even if one were to somehow force one's will to accept the scenes as related to Christ's passion and death, the final tapestry (The Unicorn in Captivity) seems antithetical to the primary Christian message of resurrection and a triumph over death and sin.

Dogs in Courtly Love Romance

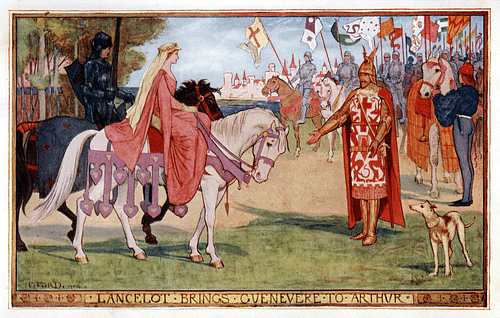

It is far more likely that the story the tapestries unfold has to do with the medieval concept of courtly love in which the noble knight battles for the safety or honor (or both) of the fair, and often elusive, maiden. The most notable examples of this motif in literature come from Chretien de Troyes (l. c. 1130-1190 CE), a poet at the court of Marie de Champagne (l. 1145-1198 CE), in the latter part of the 12th century CE. Specifically, in his Lancelot, or The Knight of the Cart, Guinevere puts the great knight through a number of humiliating trials such as telling him first to lose, and then to win, a tournament in order to prove his devotion to her.

The unicorn in the tapestries might be better understood to represent the lady who must be rescued, sometimes in spite of herself, and the hardships one must be prepared to endure to accomplish this, even to wounding the person one seeks to save. At the time the Unicorn Tapestries were created, courtly love romance was still a popular genre as it had been used by Geoffrey Chaucer (l. c. 1343-1400 CE) in many of his works and by Sir Thomas Malory (l. c. 1415-1471 CE) in his Le Morte D'Arthur. Le Morte D'Arthur, which drew heavily on the courtly love tradition, was published by William Caxton in 1485 CE and became a bestseller and so it is reasonable to assume an audience viewing the Unicorn Tapestries would have been well-acquainted with the courtly love tradition.

Aside from Chaucer and Malory, the courtly love tradition attracted the attention of some of the best-known poets of the Middle Ages including Marie de France (wrote c. 1160-1215 CE), Boccaccio, and Dante among many others. A number of the greatest works of courtly love poetry come down to the present day anonymously, however, and among these is the Chatelaine de Vergy (13th century CE) in which a dog plays a prominent role.

A chatelaine (a woman who runs a large estate), niece of the Duke of Burgundy, falls in love with a brave and handsome knight in her uncle's service. The knight returns her feelings but she makes him swear to keep their love a secret. No mention is made of the chatelaine being married or why they must conceal their love. When the knight comes to see her, he must wait alone in the garden until the chatelaine's small dog comes to get him and lead him to her. This all works well until the Duchess of Burgundy falls in love with the knight and tries to seduce him. He rejects her and, insulted, she tells her husband he tried to seduce her.

The knight is charged with treason against his lord and is in peril of being executed and so must break his promise to the chatelaine. He tells her uncle of their love, the little dog that leads him to meet her, and explains he has no interest in the Duchess and did not try to seduce the Duke's wife in any way. The Duke lets it all go and tells his wife what the knight said and how she must have mistaken his earlier intentions. The Duchess is not about to follow her husband's example in forgiveness, however, and at the feast of Pentecost teases the chatelaine about her knight and well-trained dog, insinuating that the two are one. The chatelaine realizes the knight has betrayed her trust and kills herself. When the knight finds her, he kills himself in grief. The Duke then avenges them both by killing the Duchess and devoting himself to celibacy among the Knights Templar.

Petitcreiu the Magical Dog

Another example of the dog in literature comes from one of the most popular romances of the Middle Ages, the Tristan by Gottfried von Strassburg (d. c. 1210 CE), which includes an episode featuring a small lapdog named Petitcreiu which is often cited as a favorite section even among readers in the present day.

In this story, Tristan is separated from his true love Isolt, wife of his uncle from whose court he had to flee, and is staying at the court of the Duke Gilan. He is missing Isolt and grieving his loss when he is introduced to this magical dog from Avalon, Petitcreiu, the Duke's close companion, whose coloring no one can name as it seems to change in hue depending on which angle one looks at it. Further, the dog has a gold collar with a little bell on it which rings whenever Petitcreiu moves and takes away all cares and sorrows of anyone in the room.

Tristan makes a deal with Gilan to kill a giant who has been extorting the kingdom for years in return for anything he asks. After slaying the giant Urgan, Tristan asks for the dog and Gilan tries to get him to accept any other gift but the knight refuses. Once he has Petitcreiu, Tristan sends the dog to Isolt so it will cheer her up since he knows she is pining for him as badly as he is for her.

When Isolt receives the dog she is overjoyed, knowing Tristan was thinking of her, and at first feels even happier because of the magic of the dog's bell. After only a little while, however, she has the bell removed from the dog's collar because she wants to honestly experience her feelings and not have her pain assuaged by magic. Faced with the choice of the ache of missing her lover or having that pain masked by illusion, Isolt chooses grief over solace and truth over illusion; and the instrument of her choice is a dog.

Gelert & Guinefort: Faithful Dogs

This type of story, featuring the faithful dog, was repeated with variations throughout the Middle Ages. The tragic death of one or both lovers was a popular motif in medieval literature, just as it is in the present day, but equally popular were tales of the faithful dog who featured in such stories. Dogs were no mere utilitarian addition to the home or workplace anymore as their loyalty and dependability became increasingly valued.

The dog as a loyal friend on the hunt was made popular by the legendary figure of King Arthur whose dog Cavall (also given as Cabal) was said to have left his pawprint in a stone while he and Arthur were hunting the great boar Twrch Tryth in Wales. Arthur honored his canine friend by erecting a cairn and placing the pawprint stone at the top. People would come and take the top stone as a souvenir but the next day it would return to its rightful position just as, the legend goes, a dog will always return to its master. The dog was frequently depicted in art and legend as a faithful companion and The Legend of Gelert, from Wales (c. 13th century CE), which is too often presented without question as historical fact, is an example of this.

According to the tale, Gelert was the dog of Llewelyn the Great of Gwynedd and his faithful companion for many years. Llewelyn trusted the dog so completely that he posted him as guardian of his infant son. One day, returning home, Llewelyn found the dog covered in blood and the cradle overturned. In a moment of thoughtless fury, he drew his sword and killed the dog and a moment later heard his son crying; only when he went to check the boy did he find the dead body of the wolf Gelert had saved his son from. After burying Gelert, Llewelyn was said to have never smiled or felt happiness again in his life.

The story became so popular that, by the 18th century CE, it was capitalized on by the owner of a local hotel who claimed to have found Gelert's grave and charged tourists to see it. Gelert's supposed grave remains a tourist attraction in the village of Beddgelert in the present day with memorial plaques in Welsh and English relating the story.

The legend is almost certainly taken from the story which formed the basis of the Cult of Saint Guinefort, the Holy Greyhound which flourished about the same time (13th century CE). This story has all the same elements as Gelert's tale except it takes place near Lyon, France and it is a snake, not a wolf, who threatens the child and is killed by the noble Greyhound Guinefort who is then killed by his master, mistaking the circumstances, and believing the dog attacked his son. After Guinefort's death, his master drops his body down a nearby well and fills it with stones to create a grand grave. The well later became a popular pilgrimage site for Christians seeking healing, especially women for their infants, and grew into a Christian cult centered on the dog and its healing power.

Conclusion

The dog's association with healing, the divine, and protection goes back thousands of years to ancient Mesopotamia, China, and Egypt but there is no hard evidence to suggest that anyone in medieval Europe was aware of this. It is a fascinating aspect of the relationship between dogs and humans that dogs are almost uniformly seen in the same way by civilizations around the world which had no interaction with each other. The only notable difference in how dogs were perceived is in China and Mesoamerica where, in addition to their usual virtues, they were also bred as a food source.

In the Middle Ages, the protective nature of the dog linked it to the Christian ideal of the divine while, in earlier civilizations it was associated with deities such as Gula (in Mesopotamia) or Anubis (Egypt) and regarded as a guide who moved easily between the afterlife and the mortal world (China, Mesoamerica, and elsewhere). Throughout recorded time, the dog has consistently held more or less the same position in human society while other pets have not (most notably the cat in the Middle Ages), highlighting how deeply people past and present depend on the dog for protection and the simple comfort of a good friend.