It is said that Chester is the richest city in Britain in terms of archaeological and architectural treasures. One of the finest strategic outposts of the Roman Empire, it is one of the few walled cities left in Britain today. Rachael Lindsay takes us on a personal tour of her home town.

Every time I return to my home town of Chester, tucked on the English border with Wales, I find myself going back to the majestic sandstone circuit of Roman walls, the half-timbered buildings of the city centre and the peaceful Old Dee Bridge over the River Dee.

Brushing my hand over a worn stone in the Roman Gardens, I am immediately transported back to the 1st century CE and the warm bath house of which this pillar formed a part. Standing in the gravel pit of the Roman amphitheatre, I can hear the roar of the crowd urging their gladiator to fight to the death. Gazing up to the Eastgate Clock, I wonder about every person who has done so before me.

Despite its disguise as a pretty residential town near the England-Wales border, Chester has the power to transport me across ages to the most glorious and the most difficult days in its fascinating 2,000-year history.

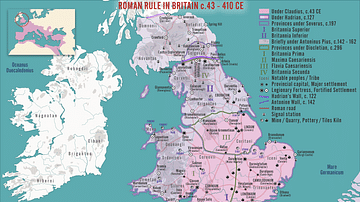

Chester started life in the late 70s CE as one of the three most powerful army camps in the Roman province of Britannia. The Romans were storming across Britannia or ”'the land of tin” building military camps and extending their empire. From their initial arrival on the beaches of Kent, they were advancing northwards and needed a base in the Northwest of Britannia, preferably near a river so that they could transport goods to and from the base.

So they built the very biggest fortress of all those built at that time, alongside the River Dee, which they named Deva Victrix - Deva, after the British name for the river that ran alongside the fort; and Victrix, after the “Legio XX Valeria Victrix” camp that was based at Deva. Deva Victrix was later to become the Chester that I call home.

Chester's Roman beginnings can best be understood by walking around the astonishingly well-preserved Roman walls and standing in the awe-inspiring Roman amphitheatre.

Its importance as a medieval city can be appreciated with a visit to the flowing River Dee, a wander through the remains of its motte-and-bailey castle or a stroll along the Rows. And to appreciate the extensive restoration and building work carried out in Victorian times, there are few better examples than Chester's cathedral and its graceful Eastgate Clock. Let us begin, however, with a stroll around the walls.

THE WALLS

The Roman walls surrounding the heart of Chester remain one of the city's most distinctive features, forming an almost-circuit of sandstone close to two miles in length. Throughout the ages, Roman centurions, Saxon soldiers and medieval archers have kept watch at these walls and, since the circuit took on recreational use in the 18th century CE, Samuel Johnson and John Wesley amongst other notable figures have taken to strolling around the walled walkway.

As well as thinking back to my days of “running the walls” with the school running club when I return to the walls today, each sandstone brick tells the story of Chester's former residents - and, of course, their enemies.

When the Romans built the fortress of Deva, it was protected by an earth embankment topped with a wooden palisade and a gate on each of its four sides. It is difficult to imagine just how imposing the fortress's gated three-metre tall rampart would have seemed to those passing by. But the army fortress quickly attracted a civilian settlement who lived in the shadow of the mighty fort, probably due to the attractiveness of trading with the Romans. As the years progressed, the fort only became more menacing as the rampart and palisade were reconstructed using locally quarried sandstone to create a solid protective wall.

By 410 CE, the Roman army had abandoned their bathhouses, homes and amphitheatre in Deva Victrix as part of the process that marked the end of Roman rule in Britain. Despite this, the Romano-British civilian settlement (which was probably made up of some former Roman soldiers and their families) stayed on, using the sturdy sandstone walls of the fortress for protection against local attack.

During medieval times, the Saxons set to work repairing, strengthening and extending the existing Roman walls, and they did such a good job of it that the sections re-built at this time still form the greater part of the walls today.

In the 17th century CE, civil war descended upon England as the whole country was gripped in the struggle between the elected democracy of the Parliamentarians and the absolute monarchy of the Royalists. The King's eldest son was the Earl of Chester so Chester, naturally, supported King Charles and the Royalists during the Civil War.

However, due to Chester's strategic position as the gateway to Wales and the fact that it was an important centre of trade, the Parliamentarians were very keen to control it. Once again, an improvement project began on the Roman walls, adding watchtowers to warn of approaching Parliamentarian troops.

But despite these enhancements, Chester's walls were breached several times during the ensuing three years of Parliamentarian attack. Legend has it that on one occasion, Chester's women were called upon to spend the night repairing a breach in the walls because the men were so utterly exhausted from the day's battle.

In the peace that followed the difficult days of the Civil War, the walls were no longer required for defence and, in 1707 CE, the decision was made to create a re-flagged walkway around the walls for its citizens to circuit the city. Today, the walls comprise the most complete Roman and medieval town wall system in Britain and almost every section of the wall is protected by Grade 1 listing.

THE AMPHITHEATRE

Chester's Roman amphitheatre, one of the Romans' grandest contributions to Great Britain, was the largest amphitheatre in Britain when it was built in the late 1st century CE. Located just outside of the city wall circuit, it is now a semi-circular sweep of gravel surrounded by crumbling sandstone and lush green grass. Each time I step foot on this site, I am both awed by its construction and slightly horrified by the thought of what went on within its stands over 2,000 years ago.

Contrary to popular belief, this amphitheatre was not a space for military training but was a civilian amphitheatre, most probably used for cockfighting, bull-baiting and combat sports. Over 7,000 spectators would assemble in the stone stands of this open-air venue, chatting to their neighbours, buying souvenirs and readying themselves for a heavily armed gladiator fight where only one man would stand triumphant once the combat reached its bloody finale.

In 2005 CE, Chester's Roman amphitheatre was the site of one of Britain's largest archaeological excavations, where it was discovered not only that the amphitheatre was, in fact, a two-storey structure similar to those found along the Mediterranean (such as Tunisia's El Djem) but that it was actually built on the foundations of a second and earlier theatre. Little is known about this earlier construction except that it was simpler than the first and probably dates back to Legio II Adiutrix, which was posted to the area in the late 70s CE.

These discoveries changed much of what historians had thought about the amphitheatre up until 2005 CE. Recent improvement works have transformed the site of the amphitheatre, making it even easier to imagine its former days of glory.

A huge mural depicting the complete amphitheatre by British artist, Gary Drostle, now forms the backdrop to the site with a new footbridge allowing visitors to enter from the perspective of a mighty, but probably fairly nervous, Roman gladiator.

THE RIVER

On a sunny day, the residents of Chester flock to the banks of the river to enjoy the gorgeous sunsets reflecting on the water and to make the most of the seasonal attractions. These include the local brass players serenading from the bandstand, the pedalos that can be sailed up and down the river's length and the kiosks that sell the ever-popular 99 ice cream.

The river's importance for leisure today contrasts with its former vitality as an economic bloodline and a route for inland trade and shipping. This economic purpose can be traced back to the days when the Saxon Kings of Wessex re-founded Chester.

Little is known about the period between the Roman's exit and the 9th century CE but Chester regained prominence in the late Anglo-Saxon era, becoming a flourishing burh or borough, thanks to its location on the banks of the River Dee. The Dee meant that Chester's residents could import wine, food and livestock from Wales, France and Spain and export leather, Chester's main industry at the time. Thanks to its location on the banks of the river, the town was flourishing.

The river also had industrial uses. In 1093 CE, the Earl of Chester, Hugh Lupus, commissioned the building of a sandstone weir slightly upstream from the Old Dee Bridge, to hold water for his corn mills. This later provided inspiration for the traditional folk song, which tells the story of a miller's delight with his machine:

I live by my mill, God bless her! She's kindred, child and wife;

I would not change my situation for any other in life;

No lawyer, surgeon or doctor e'er had a groat from me;

I care for nobody no not I if nobody cares for me.

This weir, however, contributed to the silting up of the River Dee and, as the new port of Liverpool's trading function on the River Mersey grew, Chester's dwindled. What is now the Roodee racecourse, the oldest course in the country, was once Chester's Roman harbour and part of the river – the only curious reminder of its maritime past today is the stone cross stump in the middle of the broad, bright green course, which shows the marks of water ripples on its stem.

THE CASTLE

Perched on a small hill overlooking the River Dee, the castle complex of Chester today is much changed from its original motte-and-bailey construction. But it still provides a brilliant vantage point over the river and racecourse and, each time I visit, I close my eyes and imagine being a prisoner inside the stone walls.

Following the Norman Conquest, Earl Hugh Lupus built the typical motte and bailey castle of the time from timber, which was later replaced by stone. This castle enhanced Chester's reputation as a military force and became the base for expeditions against North Wales in the 12th and 13th centuries CE.

The unlucky Welsh leader, Gruffudd ap Cynan, was captured and imprisoned in the castle for several years, during which time Earl Hugh took possession of Wales, building castles at Bangor, Caernarfon and Aberlleiniog. Gruffudd was eventually dragged from his castle prison and was fettered in the market-place for all Chester's residents to see, when, so the story goes, Cynwrig the Tall took the opportunity to rescue Gruffudd so that he could flee to Ireland. Following Gruffudd's escape, the castle's crypt continued to act as a useful gaol for important prisoners of the day such as Richard II and Yorkist John Neville during the War of the Roses.

Today, the crumbling remains of the original castle can be visited within the neoclassical complex that Thomas Harrison developed around the original structure in the late 18th century CE. It is truly like stepping back in time to enter through the Doric arches of the grand, classically-influenced gateway through to the stone Agricola Tower, the original gateway to the castle, within which wonderful religious frescoes from about 1240 CE still remain.

My favourite is the fresco of a man leaning in to embrace his lover which, although cracked and faint now, provides an impression of how stunning and ornate these walls once were. The Cheshire Military Museum, which chronicles the lives of British regiments connected with the county, is also housed within the complex in a typically neoclassical pale and symmetrical building, formerly used as a barracks.

THE ROWS

When I was growing up, I believed that every city had its own “rows”. These are a series of half-timbered black and white buildings joined with long galleries and housing shops and cafés both on the ground level and on the first floor or 'gallery' level. I quickly learnt of course that this arrangement of storey-high shops, cafes and offices entered via little stairways between shops on the ground level is quite unique to Chester – in fact, there is no comparable arrangement on the scale of Chester's rows anywhere else in the world.

Chester's rows were built during the Medieval period. At that time, the rows would have led through from shop rooms to living quarters for the craftspeople and their families. The shops would have been busy workshops with signs outside showing images of the craft created within since few people at the time would be literate. Their exact origins remain unclear but some historians think that they may have been built on top of the rubble of Roman buildings or even that Roman tombstones were used in repairs.

Before civil war descended upon England in the 17th century CE, the majority of these rows were continuous along an entire street, meaning that their first-floor galleries had no breaks to prevent free pedestrian access along the whole row of workshops.

However, Sir Richard Grosvenor, a descendant of the first Earl of Chester, began the trend for enclosing the rows when he moved his family from his country estate to his townhouse during the besiegement of Chester in 1643 CE.

Sir Richard wanted to increase the size of his house since the siege meant he was obliged to spend all of his time there. So he gained permission to enclose the row, stopping passers-by from being able to access the upper-storey gallery on the part of the row that he owned, meaning that the residents of Chester were obliged to descend and then ascend the row in order to access the surrounding shops. Being an influential figure at the time, Sir Richard's decision had an impact on the planning decisions of his neighbours who also began to enclose their sections of the row or build entirely new houses which did not incorporate the surrounding row.

Although some of Chester's residents had the means to improve their homes at the beginning of the besiegement, three years of intense Parliamentary attack on the Royalist stronghold of Chester were beginning to take their toll. Without a steady supply of food or the means to make money from trade, people were suffering terribly – not only this but also because the little money they had was being taken in taxes to contribute to repairs of the city walls.

After the Parliamentarians blockaded the single food supply route to the city, the starving residents of Chester took to eating dogs, cats and even rats in a desperate attempt to stave off hunger. Many died of starvation even so.

In January 1646 CE, Lord Byron the Governor of Chester surrendered the city to the Parliamentarians on the understanding that its ancient and religious monuments would be preserved. But the parliamentarians paid little heed to this agreement and damaged Chester's High Cross, its castle, its houses and workshops as well as several churches. Once they were finished, Chester lay in ruins.

Following these difficult days, the people of Chester began to rebuild their city, and many of the half-timbered rows that can be seen in Chester today originate from this period of rebuilding, with oak timbers painted black with tar for protection from the elements and wattle and daub painted white with lime wash.

Not every half-timbered row or building in Chester today is from the Tudor period however: some are 'Mock Tudor' buildings constructed by the Victorians. Original examples include Tudor House on Lower Bridge Street, the Bear and Billet pub just inside Southgate and the haunted house of Stanley Palace on Watergate Street.

To this day, the black and white rows remain a unique part of Chester's life with interesting shops and restaurants on the perfect level for people watching.

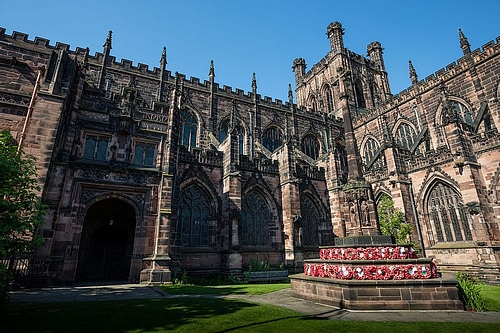

THE CATHEDRAL

The medieval sandstone building of Chester Cathedral stands proudly on the inner circle of the Walls circuit. It is a very English hotchpotch of architectural styles from its Norman north transept to the elaborate tracery of the Decorated Gothic windows and the delightful ornate choir stalls which date back to the late 14th century CE. It is a place of peace with a history that is intertwined with that of the city.

It has been suggested that Chester Cathedral's origins can be traced back to the late Roman period when some of the Romans started to convert to Christianity and build Christian basilicas. Whether or not the Romans built such a basilica in Chester, we know that by the 10th century CE, the remains of Saint Werburgh had been enshrined in a church at Chester forming an important pilgrimage site for medieval Christians. This construction was later razed to the ground and, sadly, no trace of it remains today.

Hugh Lupus, the earl of Chester weir and castle fame, endowed a Benedictine monastery on the site of the current cathedral with the help of St Anselm and other monks from Normandy in France. This medieval monastery stood for 500 years before King Henry VIII ordered the dissolution of the monasteries in England. This time, however, the buildings survived and became a cathedral of the Church of England, by order of King Henry VIII himself.

Since becoming a cathedral, the building has undergone huge restoration work over the centuries and this is why so many architectural styles can be found inside its walls. The red sandstone brick offers a warm glow to worshippers inside the cathedral but it is a delicate material that perishes easily in the English weather.

The most extensive restoration work was carried out by Victorian restorer, George Gilbert Scott, who replaced internal fittings that were destroyed during the Civil War, such as the ornate choir screen. He also made the exterior of the cathedral homogenous in its appearance, using red sandstone from nearby Runcorn.

One of the most tranquil places in Chester today is the Cathedral garden, which houses a memorial to the Cheshire Regiment as well as the first detached bell tower to be built in England for a cathedral since the Reformation.

THE CLOCK

Eastgate Clock sits majestically atop the arched sandstone structure of Eastgate on the site of the original entrance to the Roman fortress. Throughout my teenage years, ”let's meet at the clock” was a commonly used phrase as the pedestrianised area below the colourful wrought iron and copper structure made the perfect meeting place. Walking over Eastgate along the city walls also provides a great bird's eye view onto Eastgate Street below.

The clock, along with many of Chester's most prominent and well-preserved buildings, was erected in the Victorian era. In 1848 CE, the pale-bricked Italianate-style Chester General Railway Station opened and is preserved as one of only 22 listed railway stations in England. The Town Hall was also built in this period and remains a fine example of the Ruskinian Gothic Revival architecture of the time.

The Town Hall building boasts another famous clock in Chester, showing a three-sided clock tower with the side facing Wales missing, supposedly because “Chester won't give Wales the time of day”. The Eastgate Clock was built in 1897 CE to mark Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee and is said to be the second most photographed clock in Britain after London's Big Ben.

AND MY HOME

Every time I return to Chester, I am reminded once again of its fascinating stories and everything it has been through to stand today. Such stories are not only told through the impressive displays of Roman artefacts in the Grosvenor Museum or in the military archives of the Cheshire Military Museum but in the living city that Chester remains today.

I can almost feel the terror of a Parliamentarian breach when I jog the circuit of the Roman walls and am transported back to a buzzing medieval workshop when I catch up with an old friend in a café on the rows. Chester's magic lies in the fact that its history does not just live on in dusty documents but in the impressively preserved buildings, monuments and public spaces that are still being used and enjoyed by Chester's citizens today.

I invite you to come and experience the city of Chester, and my home, for yourself.