The Jade Museum (Spanish: Museo del Jade y de la Cultura Precolombina) in San José, Costa Rica houses the world's largest collection of ancient jade from the Americas. With nearly 7,000 pieces in its collection, the artifacts at the Museum of Jade reflect the creativity and beliefs of Costa Rica's indigenous peoples, as well as their rich economic and cultural exchanges with the civilizations of Mesoamerica. In this exclusive English-language interview, World History Encyclopedia's James Blake Wiener speaks to Curator Virginia Novoa Espinoza about the museum's magnificent collection and the artistry of Costa Rica's pre-Columbian peoples.

JBW: Dr. Virginia Novoa Espinoza, thank you for speaking with me on behalf of World History Encyclopedia (WHE). When many people hear of jade - a green, semi-precious stone - they think of China or Korea instead of Central America.

Jade, however, was found throughout Central America in ancient times and prized by the indigenous peoples of Costa Rica. What can you tell us about the symbolic meaning, the social use, and the function of jade in ceremonial activities in ancient Costa Rica?

VNE: For the pre-Columbian people of Mesoamerica and this part of Central America, jade was related to fertility, water, and power; perhaps it captivated people in the past for being a scarce mineral, hard to find in their territories, for its hardness, brightness, range of green tones, among other important characteristics.

As such, jade was used to carve not only body adornments - pendants, beads, nose- and earrings - but, with it, they created symbols characteristic of their system of beliefs. In Costa Rica, it was linked to animism, a basic principle of shamanism, which assigned a soul to the natural elements or to objects of daily use and different types of animals. Figures of these animals in jade or other materials were not considered a simple representation; when carrying these objects, you were carrying the recreated animal's fierceness, agility, silence, to protect and mediate between the people and the spiritual world.

Between 500 BCE and 800 CE, there were significant social changes linked to the increasingly sedentary lifestyle and agricultural developments, resulting in a gradual population increase, the forming of disperse village communities with specialized craftspeople working with different materials; a process marking the dawn of rank societies, the emergence of such functions as chiefs, spiritual leaders, farmers, among other members forming the social group.

Jade, with its implicit symbolism, was a prestige marker among these leading characters and their families; similarly, its social function was always like a talisman, the mediator between the people and the spiritual world or underworld. So, it was used during ceremonies and festivities related to funerary rites, healing practices, and agricultural events, or as funerary offerings.

JBW: The Museum of Jade showcases approximately 2,500 jade objects. How did jade reach what is present-day Costa Rica in ancient times, and how did indigenous people craft such exquisite pieces of art?

VNE: The significant quantity of pre-Columbian jade objects in the museum gives us an idea about the scale of production in present-day Costa Rica between 500 BCE and 800 CE. Of course, the time range is ample, but such quantities of jades are not yet reported for the rest of Central American countries. From my perspective, this indicates that Costa Rica's pre-Columbian settlers had specialized craftspeople carving rocks and minerals; when they grew acquainted with jade as raw material, it captivated them, and it became important at the social and ideological level attributed to it by other cultural groups.

What is called jade comes from metamorphic rocks composed by the mineral jadeite nephrite, the main source reported in the valley of the Motagua river in Guatemala. This makes jade unique; geologists have not identified any source of this material in Costa Rica, given the country's recent geological formation. This suggests a technological exchange, a transfer of knowledge, which took place following different routes of reciprocity, from south to north or vice versa. This permitted exchanging knowledge of lapidary art (jade carving) with the Olmec and Maya civilizations and finished artifacts from those areas, as attested by some jades of Mesoamerican production found in archaeological contexts of Costa Rica which may be observed in the museum's collection. In my opinion, the jade phenomenon was an important factor within the social dynamics and population movements throughout America.

It is clear there is more to investigate about the jade route from the primary source, following different collection points possibly near the Gulf of Mexico, Soconusco in Mexico, in Copán or the Gulf of Honduras, Chalchuapa in El Salvador, among other points, from which this raw material could have moved by land or sea until reaching this part of Central America. Jade concentrated particularly in two regions of Costa Rica: the northern zone and the Central Caribbean, and so some researchers mention them as possible workshop locations.

The Olmec civilization was the first to carve jade, and later, the Maya followed suit, both being noted lapidary centers. However, since pre-Columbian times, jade-working also reached a significant level in Costa Rica, with local styles portraying indigenous beliefs. Another element to consider is the large amount of objects found in the archaeological contexts.

One of jade's characteristics is hardness which requires great skill and tools such as leather strings, woods, jade or quartz-point drills and abrasive sands (mainly with quartz content) as well as a water source near the workshop. Without going into too much detail, some techniques consisted of perforating the blocks with a jade-point drill (taladro de balance), then joining the holes with string, and forming the desired shape using abrasive sands and water. Many of the figures have bi-conic holes to hang them because the object was drilled on both sides. Jade's brightness is characteristic, translucid; the final finish or gloss was achieved by rubbing the piece with leather, wood, abrasive sands and beeswax. The predominant shapes are hatchets, generally decorated with human or animal figures carved on the upper part of the handgrip, and body adornments, earrings, nose rings, and necklaces among others.

JBW: Although the Jade Museum was founded in 1977 CE by Marco Fidel Tristán Castro, the collection is currently housed in a new five-story structure, which opened in 2014 CE. Stressing the distinctiveness of the museum's holdings, Costa Rican architects sought to evoke a connection between the building's architecture and the shape of jade itself.

How has the museum chosen to organize its immense collection of jade?

VNE: The Jade Museum is part of the semiautonomous Costa Rican entity, the National Insurance Institute (INS); it has been the custodian of this collection of 7,000 archaeological objects, including 240 ethnographic pieces and 360 works of contemporary art. We take our role in safeguarding the country's cultural heritage very seriously.

The museum was established as an archaeological collection in 1977 CE on the 11th floor of INS' main building. The exhibition was relocated in 2006 CE to the ground floor of INS an in 2014 CE to the current building of the Jade Museum and of pre- Columbian Culture. The building's architectural design was proposed by architect Diego Van Der Laat; its aspect evokes a block of jade sectioned in half, through which light comes in and is distributed throughout the five exhibition floors. Similarly, visitors are greeted in the lobby by a block of jade (uncut) brought from the Motagua River Valley, as a sensory experience regarding the texture and color of this raw material.

I was in charge of the curation of this permanent exhibition, with the responsibility of assessing all this archaeological heritage which consist not only of jade pieces but also other materials. I decided to plan an explanatory thematic proposal; it is not linear or chronological but the objects lead us in a particular narrative through Costa Rica's ancient history, with the purpose of highlighting aspects of cultural identity, social organization, and human diversity in the pre-Columbian world. The permanent exhibition's scientific proposal develops 16 themes and 51 subthemes, approaching different social, cultural and technological aspects of pre-Columbian societies, with the objects museographically arranged in four rooms according to each theme.

The museum has one of the best collections of pre-Columbian jade of America, which led to the main conceptual theme, jade working, its symbolism and aspects relating to social and spiritual power and its context. Other thematic areas are developed around diverse social, economic, political and ideological themes distributed in different rooms with suggestive names like "jade," "day," "night," and "ancestral memory."

JBW: The Museum of Jade also contains thousands of priceless objects made of stone, gold, shell, and bone, in addition to ceramics, adzes, ceremonial stone sculptures, and other richly decorated specimens that date from c. 500 BCE - c. 800 CE.

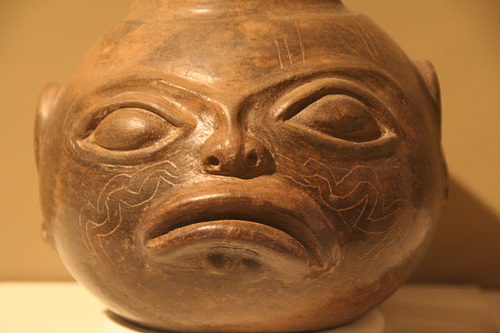

VNE: The archaeological collection under the custody of the Jade Museum is comprised of objects in different materials such as jade, stone, wood, bone, shell, and resins. They were made for the daily and ideological needs of the settlers of this territory during the pre-Columbian period. The variety of shapes and finishes of the pieces let us infer they were intended for multiple functions within the community, but these objects also help researchers interpret general aspects of the social changes, chronology, and technology.

The collection of objects is in good state of conservation; other characteristics serve as a supporting database for comparative analysis, used by national and foreign researchers, or students of different fields such as archaeology and art, among others. At international level, some of the museum's relevant pieces in jade, ceramics, and stone have been shown in different temporary exhibits in North America, Mexico, and Spain. In the area of stonework, ceremonial metates stand out, since they were carved under the dish using haut and bas-relief, depicting transformation scenes and their spiritual world. The collection has objects from different archaeological regions and periods, but more important than dates, the exhibition shows the human beings behind the artifacts, their everyday objects.

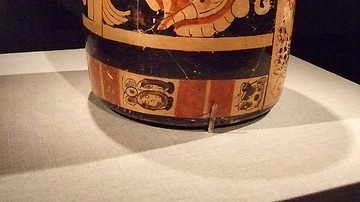

JBW: The ceramics from Costa Rica's Nicoya Peninsula, which is situated on the Pacific Coast, are most interesting as they seem to reflect cultural and economic exchanges with ancient Mesoamerica. Can you tell us more about these ceramics and the exchanges between native peoples in Mesoamerica and what is present-day Costa Rica before the arrival of the Spanish in the 16th century CE?

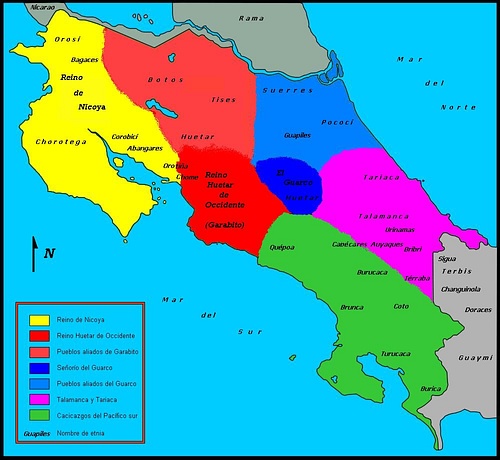

VNE: Yes, in this sector of Costa Rica's North Pacific is what is culturally known as the "Greater Nicoya Archaeological Region," where important social changes took place, particularly from 800 CE. Ceramics' decoration developed from using bichrome (two colors) to polychrome with mixed styles using Mesoamerican motifs (Tlaloc, Winged Serpent, Tezcatlipoca, Ehécatl, Cruz kan, seating human figure with headdress among others) and local elements. Before going into this, it must be noted that according to linguistic studies the first settlers of what is Costa Rican territory today were related to Chibcha groups of South America.

Some researchers think there were various factors contributing to the arrival of Mesoamericans to the Greater Nicoya; I would say it was political pressure and collapse occurring in southern Mexico around 800 CE that forced some groups (Chorotegas and Nicaraos) to migrate to other places they knew via exchange and trade, in this case to the coasts of Costa Rica's Pacific, where they settled, bringing their own culture. Spanish chroniclers identified and described these Mesoamerican groups in the 16th century CE; few documents mention the original settlers: Corobicíes, Ramas, Votos. I emphasize there was syncretism in the territory which is now Costa Rica, reflected not only in the elaboration of polychrome pottery but in the funerary practices, in their settlements, and the physiognomy of people.

JBW: Another treasure at the Jade Museum and one of Costa Rica's enduring archaeological mysteries are the mysterious stone spheres (Spanish: Las Bolas de Costa Rica). The Jade Museum has three of them on display in its permanent collection. Where do they come from, when were they made, and what do we know about them?

VNE: The stone spheres are iconic pre-Columbian artifacts; they were produced from c. 300 BCE in Costa Rica's South Pacific, what archaeologists call the Diquís Sub region. They were crafted from igneous and sedimentary rocks; their size varies between 15 cm to 2.5 m in diameter. The sculpting technique for this type of object required access to a stone quarry with gabbro, granodiorites, limestone in order to find the appropriate block and shape it by grinding with stone hammers and chisels and sand.

I think the mystery is revealed when we turn our sight to the craftspeople specialized in carving stone who had the ancestral knowledge of modeling any type of material; we see it in other Costa Rican jade artifacts, decorated ceremonial metates, which are outstanding at American level for their motifs and decorations. The spheres were used as landmarks in public areas, in funerary contexts, and also as rank symbols. In some cases, they are aligned at sites of complex architecture. Here I wish to mention that, in June 2014 CE, four settlements with pre-Columbian stone spheres of Diquís were declared World Heritage by UNESCO.

JBW: Among all of the artifacts at the Jade Museum, which ones hold special meaning to you and why? Additionally, do visitors to the museum comment frequently on any artifacts in particular?

VNE: As the curator I have been quite close to the whole collection, choosing the pieces for each theme. From my training as archaeologist, I would say each one of these pieces has its peculiarity; they do not cease to fascinate me with the mastery of the applied technique in all types of industry (jade, gold, bone, shell, stone among other materials) achieving realistic figures with stylizations, with an awesome synthesis and also the ideological ingredient they added to each object.

It is clear that jade pieces made in Costa Rica stand out with their local style. If I have to choose, I will go for the jade pendant with two bird heads, which represents duality and, in fact, this is where the museum's logo came from. The jade figure evokes the association with the vulture position (scavenger bird) posed with open wings as when drying its plumage, even granting it a mystical image, changing from bird crossing the air to one that although posed still has outstretched wings. The figure in this position with two heads, materialized in jade as an element of power, symbolizes a dual relation (two natural or psychological phenomena), the bird of prey that being a scavenger may be related to life and death, guiding souls to the afterlife (psychopomp).

Visitors are always curious about the diverse objects exhibited in the different rooms; among the most attractive ones are the hatchets carved in jade, necklaces, the spheres, barrels, hanging panel metates, the ceramic feminine figure with body painting , the ritual pole made of volcanic rock, the ceramic pipes and inhalers, the polychrome vessels, and the incense burners with cover.

JBW: Every year, Costa Rica is visited by over 2 million foreign tourists, who come to explore the country's national parks, rainforests, volcanos, and beaches. In your own words, why should they also come and visit the Museum of Jade in San José?

VNE: Costa Rica has the privilege of possessing 6% of the world's biodiversity, expressed in the different ecosystems (tropical rain forest, cloud forest, dry forest, extensive volcanic mountain ranges, wetlands, moors; even a volcanic island), something tourists from different parts of the world can enjoy first hand. These wonders of nature also provided human beings in the past with space to establish their home and means of subsistence (food, water, raw materials); their constant interaction and observation of the flora and fauna gave origin to myths and beliefs to explain supernatural aspects.

These beliefs are expressed in realistically depicted or stylized animals and fruits in different materials as a way of recreating their natural environment. If a tourist visits the different ecosystems and is lucky enough to see, for example, the diversity of fauna in its natural state, there will be a point of comparison, when visiting the Jade Museum, to admire how craftsmen portrayed many bird species, reptiles, fish, turtles among other animals in these objects. When you visit a museum anywhere in the world, it is the synthesis made by learning of the different cultural groups forming and consolidating the current inhabitants of that country's identity which lets you understand their habits, physiognomy, and ancestral memory. Therefore tourists should not only visit the beach and volcanoes but also learn about the history of the people; for that, you have the Jade Museum in San José, Costa Rica.

JBW: Thanks so much for your time and consideration, Dr. Virginia Novoa Espinoza! I enjoyed learning about the Museum of Jade, and I hope to visit Costa Rica in the near future.

VNE: My pleasure. We hope that you and your readers can make it to Costa Rica and come enjoy a tour of the Jade Museum's archaeological exhibition rooms.

Virginia Novoa Espinoza obtained her BA in Anthropology at the University of Costa Rica, where she graduated as Licentiate of Archaeology, with honors (University of Costa Rica). She later earned her MA in Anthropology at the University of Costa Rica as well. She has been the Curator of Archaeology in the Jade Museum since 2003 CE, and she has experience in the preparation of scientific scripts, supporting museographical and educational texts. She was formerly in charge of managing the museum's archaeological collection from 2004-2014 CE. From 2003 to 2016 CE, she taught archaeology courses at the School of Anthropology with the University of Costa Rica. She has participated in lectures and training workshops with different audiences - tourist guides, primary and secondary school students, teachers, visitors in general - on archaeological subjects. Widely published in newspapers, journals, and books, Virginia Novoa Espinoza has also lead many workshops and works as a consultant in the field of archaeology.