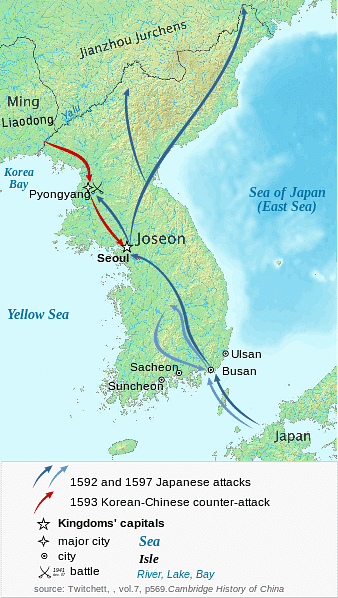

The two Japanese invasions of Korea between 1592 and 1598 CE, otherwise known as the 'Imjin Wars', saw Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1537-1598 CE), the Japanese military leader, put into reality his long-held plan to invade China through Korea. The ambitious campaign got off to a brilliant start as cities like Pyongyang and Seoul were captured, but eventually, the combined operations of the Korean navy led by Admiral Yi Sun-sin, a large land army from Ming China, and well-organised local rebels resulted in the first invasion stalling in 1593 CE. After protracted and unsuccessful peace talks, Hideyoshi launched a second, much less successful invasion in 1597 CE, and when the warlord died the next year, the Japanese forces withdrew from the peninsula. One of the largest military operations ever undertaken in East Asia prior to the 20th century CE, the conflict would not only have devastating consequences for all concerned but permanently sour relations between Japan and Korea.

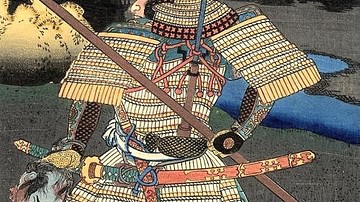

Toyotomi Hideyoshi

Toyotomi Hideyoshi was a gifted general who took over the position as Japan's most powerful military leader following the death of his superior Oda Nobunaga in 1582 CE. Both men contributed greatly to unifying Japan, and the economic and military power this put into the hands of Hideyoshi proved all too tempting. The warlord wanted an empire.

Hideyoshi's plan was nothing less than to conquer Ming China (1368-1644 CE), but to do that he first needed to control Korea or at least march right through it. Indeed, Hideyoshi's scheme was so ambitious some historians have taken it as evidence of a mental disorder which manifested itself in other forms such as his paranoia that those closest to him, including his nephew and first-choice heir, were conspiring against him. Whatever the warlord's mental state, he did not perhaps have an exaggerated view of his own martial abilities as he did not personally lead his armies in Korea. Some have also argued that Hideyoshi was not as mad as all that and he was shrewdly sending his most powerful generals on a foreign expedition to keep them from stirring up trouble at home. Whatever the precise motivations, the first campaign bore the hallmark planning of the warlord's great campaigns in Japan. The invasion might be hugely ambitious, but if anyone could pull it off, it was Toyotomi Hideyoshi.

The First Invasion

In April 1592 CE Hideyoshi amassed a huge fighting force which consisted of 158,000 warriors and a navy with 9,200 mariners. In reserve, he had another 100,000 armed men stationed ready in northern Kyushu. The invading army, with its headquarters at Nagoya in Hizen, was led by three powerful daimyo or feudal lords: Kato Kiyomasa, Konishi Yukinaga, and Kuroda Nagamasa. A naval fleet was assembled with most of the ships being manned by former wako or pirates. Sailing in May, the army arrived near the port of Pusan (Busan) at the southeast tip of the Korean peninsula and got off to a flying start by capturing the fort there despite stiff resistance to the last Korean man and then, even more significantly, defeated a Korean army led by General Sin Ip at the battle of Chungju. The invading army, benefiting from the triple boons of planning, professionalism, and firearms (which the Korean army lacked), captured Seoul on 12 June. The Koreans were caught entirely by surprise and King Seonjo (r. 1567-1608 CE) fled to the north of his country.

The Japanese force then split into three, one part, led by Konishi Yukinaga, headed for and captured Pyongyang on 23 July while another, commanded by Kato Kiyomasa, marched to the northern frontier with Manchuria and the Yalu river. Meanwhile, Kuroda Nagamasa took his force to the northeast. Still more units moved to hold the centre and south of the peninsula. Phase one of the invasion was complete and successful. Phase two was to now attack China and to that end, supplies were gathered by force from the Korean farmers and even taxes were collected. So far, everything seemed terribly efficient on the part of the invaders.

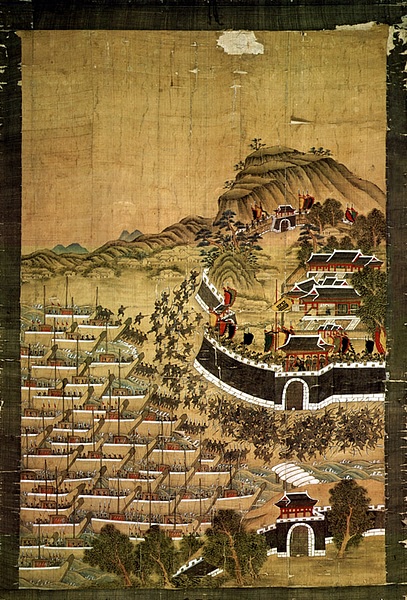

Then the Japanese came against a large and stubborn stumbling block: the Korean navy. Commanded by the gifted admiral Yi Sun-sin (l. 1545-1598 CE), the fleet had a small number of 'turtle-ships' (kobukson) - perhaps only five - which had covered decks making them difficult to board or inflame. Besides being equipped with cannons, a dragon's head which spewed smoke and protective spikes, it is possible (concrete details are lacking) that the decks of these ships were covered in iron plates making them the world's first ironclad battleships. Yi Sun-sin attempted to cut off the resupply of Japanese-held Busan. This he did not quite manage but he did win several naval engagements (Haengju, Chinju, and Hansan Island) and so blocked the Japanese from entering the Yellow Sea where they were needed to give crucial support to the Japanese armies in the north.

Logistics became decisive, and the supplies of the Japanese land forces dwindled. Another problem was the harshness of the Japanese occupation, which resulted in several peasant uprisings and a campaign of resistance which disrupted even further the army's logistics and lines of communication. The crucial factor, though, in the future turn of events was the intervention of the Chinese. Emperor Wanli (r. 1573-1620 CE) of the Ming Dynasty, perhaps realising that this was indeed only stage one of a planned attack on China itself and morally obliged to fulfil the obligation of the East Asian tributary system where neighbouring states sent tribute to China, dispatched a small army led by General Li Rusong to aid the Koreans in July 1592 CE. This force was easily rebuffed, but Wanli was not deterred and he sent a second, much larger army of perhaps 50,000 men. Arriving in Korea a few months later, the Chinese defeated the army led by Konishi Yukinaga at Pyongyang in January-February 1593 CE. The Japanese commander was compelled to retreat back to Seoul. From there, Konishi negotiated an end to hostilities but the Japanese remained in occupation of the southern half of Korea for the next four years.

Armistice & Diplomacy

Then a series of negotiations, subterfuge and delay tactics ensued between the three powers. In June 1593 CE, the Chinese sent an envoy to negotiate directly with Hideyoshi in Japan. The Japanese warlord was either mad or daring or both as he demanded of the Chinese emperor impossible terms. He asked for a return to the old system of tribute trade, a marriage of alliance between the emperor of Japan and a daughter of Emperor Wanli, and four provinces of southern Korea. Seeing that such an approach would not lead to any agreement, Konishi, still in Korea, made diplomatic manoeuvres of his own to persuade the Chinese that, through him, Hideyoshi might ultimately accept a theoretical vassal status to the Chinese emperor. Konishi even went so far as to forge a letter from Hideyoshi in which the warlord was referred to as the 'King of Japan.' The Chinese were willing to bestow this title upon Hideyoshi and so ambassadors were sent to Osaka in December 1596 CE. The warlord was not best pleased to discover the arrangements made behind his back. The Chinese envoys were dismissed, and preparations were made for a second invasion of Korea.

The Second Invasion

The reserve army of 100,000 men was now sent across to Korea to bolster the Japanese forces already there. In August 1597 CE Hideyoshi set them the task of permanently annexing for Japan the four southern provinces of Korea. The object was much more limited than the first invasion, but this time several factors were against the Japanese right from the start. First, the Koreans now knew what was coming and were much more prepared. Second, a Chinese army was now already in Korea. Third, the excellent Korean navy, still commanded by Yi Sun-sin (back after a brief imprisonment thanks to his rivals' machinations), had not gone away and still controlled the coastal waters.

Despite these disadvantages and like the first time around, the invasion got off to a good start and made headway towards Seoul but the winter of 1597-8 CE did not help the campaign, and Konishi had to resort to defending his position at Busan and a line of coastal forts (wajo). Meanwhile, Yi Sun-sin won a decisive naval battle at Myongnyang. The Japanese occupiers were further harassed by the local peasantry and bands of guerrilla fighters, the ubyong or 'righteous armies' which included monks in their ranks. It now looked a distant dream to ever control Korea, never mind mobilise into Ming China. Then fate showed its hand. When news of Hideyoshi's death arrived in September 1598 CE, an armistice was arranged between the three powers and the invasion was abandoned. Despite the supposed ceasefire, many Japanese troops had to fight their way to the coast before being shipped back home. In the harrying of the Japanese withdrawal, Yi Sun-sin was killed by a lucky bullet. It was an unjust end to the man most responsible for saving Korea. The admiral's diary of the war, Nanjung-ilgi ('Daily Writings during the Troubles') was posthumously published.

Consequences & Aftermath

Korea

The most immediate of the many consequences of the wars for the Koreans was the death of at least 125,000 of them. The Japanese samurai frequently cut off the nose and ears of their victims and sent these back to Japan as proof of their kills. There was also the removal of 60-70,000 Koreans, taken as prisoners of war to Japan. Korea was ravaged by the invasion, and its agriculture suffered terribly because of the Japanese scorched-earth policy; production levels would take two centuries to recover. In the cities, too, there were dire tales of death, starvation, and disease. Seoul, in particular, saw its population plummet from around 100,000 to 40,000. In addition, many important Korean cultural sites (notably Bulguksa Temple near Gyeongju), libraries, and artworks were either destroyed or spirited away to Japan. Finally, the Koreans did not quite manage to rid themselves of the invaders. A small Japanese settlement near Busan with a contingent of samurai for protection was maintained.

China

The Ming dynasty had been in decline under Emperor Wanli long before the Japanese invasion of Korea, especially when he had withdrawn from court affairs in 1582 CE following the death of his talented Grand Secretary Zhang Juzheng. The power vacuum was willingly filled by the court eunuchs, but it was the huge cost of the wars both with the Mongols and the Japanese that caused the Chinese economy to nosedive. Within 50 years, the Ming would be toppled first by rebels and then by the Manchus, founders of the Qing dynasty (1644-1911 CE).

Japan

Hideyoshi had died of natural causes on 18 September 1598 CE, and with him went the fate of the Korean campaign as his successor Tokugawa Ieyasu (r. 1603-1605 CE) abandoned the idea of creating an East Asian Empire. From 1607 CE diplomatic and trade relations were restored with Korea and would endure for a further two centuries, even if the wounds of the Imjin Wars would never really heal.

On a more positive note, the Imjin Wars are sometimes referred to as the 'Pottery Wars' because many Korean pottery artists, already much admired for the white porcelain they had been producing in great quantities, were forcibly relocated to Japan during the conflict. These exiles would have a significant influence on Japanese ceramics, especially Satsuma ware, and create a boom in Japanese wares from the 17th century CE onwards. Other ideas came to Japan with captured scholars like Kang Hang (l. 1567-1618 CE) who introduced Neo-Confucianism to the country.

This content was made possible with generous support from the Great Britain Sasakawa Foundation.