The battle of Cynossema, in 411 BCE, was an Athenian victory during the final years of the Peloponnesian War. It marked the resilience of the renowned Athenian democratic system after their major defeats in Sicily and also after a small civil war within Athens. This victory, narrated by the famous Ancient Greek historian Thucydides, was crucial for the maintenance and balance of power in the Aegean Sea which was the main theatre of combat in the concluding years of the conflict. This defeat over the Spartan fleet demonstrated the utmost strategic importance the Athenians gave to the Hellespont straight which functioned as one of the major arteries for their empire and the Delian League.

Thucydides

Our main source for the battle is Thucydides (c. 460/455 - 399/398 BCE), an Athenian general and historian, the author of the History of the Peloponnesian War, which tells a contemporary story of the conflict between Sparta and Athens in the final years of the 5th century BCE. It is clear in his writing style that he was heavily influenced by famous playwrights of his time like Sophocles and Euripides and also by Socrates in some of his philosophical views about the Greek world and city-states. Xenophon, continued in Thucydides' footsteps after he abruptly stopped writing about the final years of the war, thus elevating himself to the main source for modern-day historians after Thucydides.

The Peloponnesian War

The Second Peloponnesian War (431-404 BCE) was a conflict that had been already going on for two decades years before the Battle of Cynossema. Its impact on the Hellenic world was astonishing, it changed forever the balance of power of the Greek city-states but, more importantly, it changed the Greeks themselves. They had never experienced a prolonged war like this one. The Peloponnesian War is the perfect example of the classic war dichotomy of land power versus maritime power. The Athenians held the dominion of the seas while the Spartans and their allies had control over the land. However, Athens was protected by enormous city walls that covered the entire city plus its port. Athens was this way self-sufficient and invulnerable to land attacks and prolonged sieges, as long as it had a navy to collect tribute and import goods to the capital. On the other hand, Sparta was protected by two parallel mountain ranges in the centre of the Peloponnesian Peninsula, this way, as long as it held military control over the land, its capital was safe.

The war began with a small local rivalry between the island of Corcyra (modern-day Corfu) and the city of Corinth. The first phase of the war, normally called the Archidamian War, was marked by low war enthusiasm and slow movements of troops that operated normally only in summer. The two leaders of the warring factions, the Spartan King Archidamus and the Athenian leader Pericles, were against the war and were pushed to it by their people and allies. This phase of the war was marked by some victories and defeats by both sides, which had little impact on the overall picture of the conflict.

The war entered its second phase after the victory of Athenian general Demosthenes at the battle of Pylos and, especially, on the island of Sphacteria. This great military victory over the Spartans on their field of expertise (land battles) caused great turmoil in the Greek world because it destroyed Sparta's reputation. This forced a truce between the Spartans and Athens called the Peace of Nicias in 421 BCE. The truce was short-lived because of the campaigns of the Spartan general Brasidas in Thrace and other political factors inside Athens and Sparta's elite. Alcibiades persuaded the population of Athens to campaign against the Greek colonies of Sicily, a manoeuvre that ended in disaster.

The Athenian defeat in Sicily brought colossal repercussions in the immediate aftermath. Reflecting the Spartan defeat in the Battle of Sphacteria, the failure of the Athenians in Magna Graecia destroyed not only their empire's best generals (Demosthenes and Nicias) but also the myth of maritime invincibility of their navy. The news of this disaster overwhelmed the Delian League. Firstly, it brought severe political consequences at the internal level, especially in Athens. An enormous democratic scepticism evolved in the capital and, gradually, giving rise to a new populist oligarchy at the heart of the empire. Sparta, following the advice of Alcibiades, adopted an offensive war strategy in order to take advantage of their newfound strategic superiority. Because of this, the Peloponnesian League managed to incite numerous rebellions within the Athenian Empire across the Aegean Sea, mainly in the islands of Rhodes, Miletus, Chios, and other prominent city-states in Asia Minor.

When the oligarchs seized power in Athens, the centre of gravity of the Athenian Empire shifted towards the geographical heart of the Aegean, and the bulk of the democratic fleet (not loyal to the new government in the capital), made its headquarters of operations in the island of Samos, which became the de facto capital of the Delian League while Athens was left to its destiny; its strategic importance was severely reduced. However, the Hellespont, in the north of the Aegean, was controlled by the Athenians who taxed the passage and controlled the import shipments of grain and supplies that feed the Delian war machine.

Although the democrats in Athens managed to retake control of the city, their political legitimacy was still questionable at the time of the Battle of Cynossema. The main catalyst of the battle was probably Tissaphernes, the Persian Satrap of the Asia Minor regions of Lydia and Caria. This local governor conspired with Alcibiades before in order to supply logistical aid to the Spartans in the Aegean. His goal was to reconquest the Greek poleis in Asia Minor. However, when the support did not arrive, the Spartans looked elsewhere, mainly in the northern regions of Asia Minor, where the Satrap Pharnabazus, the local governor of Dascylium in Phrygia, ruled and promised them money and help.

Battle of Cynossema

The Athenians were occupied with their operations in the Aegean when they received news about movement of the Spartan fleet northwards. Rapidly, they sailed to intercept the enemy before they reached the strait of the Hellespont. However, Mindarus, the Spartan general, due to a strong storm in the region of Icarus, decided to stop halfway and resupply on the island of Chios. Thrasyllus, an Athenian general who operated in the Aegean, heard of this and attacked the city of Eresus, on the island of Lesbos, to lure the enemy to attack them there and make them fight on his own terms. Meanwhile, he was waiting for reinforcements from the Hellespont, under the leadership of another Athenian general called Thrasybulus.

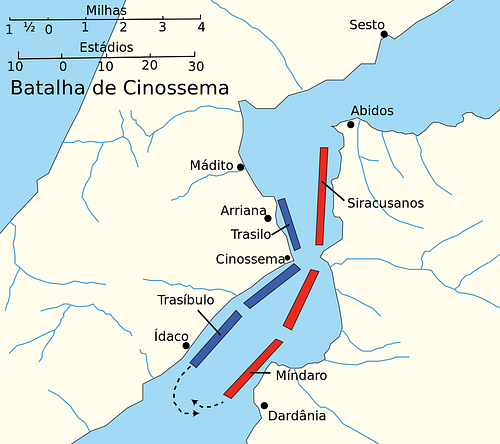

The Spartans were not compelled by the trap and sailed along the eastern part of the island of Lesbos to avoid detection. Mindarus managed to reach the Hellespont and close the strait with a fleet composed of 86 ships and Mindarus camped his army between the villages of Abydos and Arcanania. This closed one of the main pathways of the Delian League and threatened economic collapse and hunger. The two Athenian generals had to invest everything they had in the effort to retake the strait through a large-scale maritime battle, so they sailed to the Dardanelles with a fleet of 76 trireme ships.

Realizing that a battle was now imminent, both combatants extended their flank; the Athenians along the Chersonese from Idacus to Arrhiani with seventy-six ships; the Peloponnesians from Abydos to Dardanus with eighty-six. (Thucydides, Chapter XXVI)

The two fleets met with the ships positioned parallel to the coast; the Athenians in the European side and the Spartans in the Asian side of the strait. Mindarus organised his navy in a straight line, with their allied Syracusans on the right, the most experienced troops in the centre, and commanding the left himself. The Athenians arranged their ships akin, with Thrasybulus on the right and Thrasylus on the left. The objective was to push the enemy hard enough to force them ashore and destroy them completely. With this in mind, the Athenians gambled everything on this battle and were completely conscious that defeat could jeopardise the whole war.

The battle started with the Spartan triremes attacking the Athenian fleet. Mindarus tried to outflank the Athenian right in order to trap them inside the strait and thus prevent the enemy fleet from retreating to the Aegean. However, Thrasybulus foresaw this movement and, acting quickly, stretched his line to be wider than Mindarus' and tried to outflank the Spartan left instead. However, to widen the line, the Athenians had to transfer ships to the flanks, leaving the whole line weak and fragile to strong attacks. The Athenians traded strengths for manoeuvrability.

When the Peloponnesians saw the enemy spreading their lines, they seized the opportunity to charge harder, and the Spartans in the centre and their allied Syracusans on the right managed to push the Athenians to the coast. The battle was now reduced to the Athenian right and their capability to outflank Mindarus. Thrasybulus launched his forces boldly and was able to crush Mindarus. Meanwhile, the rest of the Peloponnesian navy was distracted by their swift victory and did not even notice that the left side of their fleet was lost. Thrasybulus took advantage of this situation and charged the strait northwards swiping the entire Spartan and Syracusan fleet, taking them by surprise. Due to the panic that ensued, the Peloponnesians fled just to be caught and destroyed moments later by the Athenians.

Up to this time they had feared the Peloponnesian fleet, owing to a number of petty losses and to the disaster in Sicily; but they now ceased to mistrust themselves or any longer to think their enemies good for anything at sea. (Thucydides, Chapter XXVI)

After the battle was won, a trireme was sent to Athens with the news of this victory. The entire Peloponnesian navy was destroyed and the Delian League regained de facto control over the Mediterranean Sea. In Sparta, King Agis II was replaced by his younger half-brother Agesilaus, and it was at this point in time that the ambitious Spartan general Lysander makes his first appearance. He rebuilt the Spartan navy with the help from the Persians and insisted on an offensive maritime tactic in order to inflict a decisive blow to the enemy and thus win the war. A few years later Lysander had the opportunity to attack the Hellespont, and he did exactly that having learned from the mistakes at Cynossema. He won the battle against Alcibiades that was recorded as the Battle of Aegospotami. This victory caused serious logistical problems to the Athenian Empire, and a few days later Lysander conquered the Piraeus and Athens. This officially announced the end of the Peloponnesian War.

Conclusion

In the Battle of Cynossema, we see the witness the unsullied Athenian military discipline, even after years of war, and even being this a decisive battle that would determine the outcome of their empire. Victory can be attributed to two simple elements; discipline and experience. The Spartans had more manpower, were better supplied, and their troops were superiorly equipped compared to the Athenians. Despite holding the upper hand most of the time during the battle, the Peloponnesians were not able to fulfil their objective. The lack of discipline of the Syracusans and the Spartans resulted in the destruction of their fleet; something that could have been easily avoided had they maintained their formations to repulse the attack from Thrasybulus after he defeated Mindarus.

Donald Kagan, in his book The Peloponnesian War, emphasised that the Athenian population rejoiced at the news of this victory and it reinforced the legitimacy of their newly reinstalled democratic regime. This contributed heavily to the extension of the war that offered the Delian League the opportunity to regain superiority in the Aegean Sea. Nonetheless, the Spartans did not forget the importance of the strait of the Hellespont, later in the war, it proved itself to be the Achilles heel of the Athenian Empire and the key to its destruction.