The Unam Sanctam (1302) was a papal bull issued by Pope Boniface VIII (served 1294-1303) requiring the complete submission of all people, including kings, to the authority and dictates of the pope. As the Church was understood as holding the keys to heaven and hell, and the pope was head of the Church, failure to comply threatened salvation.

The medieval Church developed and retained its power by encouraging the innate human fear of death and the Church's vision of itself as the only path to salvation from hell. The pagan systems of the past all had some version of judgment after death whereby good people were rewarded and bad people punished, but Christianity claimed there was no such thing as a 'good person' and the soul's final destination was entirely a matter of God's mercy in administering divine justice.

The biblical Book of Romans 3:10 makes clear "there is none righteous, no, not one" and develops that concept through 3:23: "For all have sinned and come short of the glory of God." The author of the epistle to the Romans, Saint Paul, continues this theme in Chapter 6 in which he explains how once one accepts Christ as savior, one is baptized into Christ's death and resurrection, and one's old, sinful self is reborn (Romans 6:3-11). The rest of Romans 6 is an admonishment on sin, ending with the famous line, "For the wages of sin is death; but the gift of God is eternal life through Jesus Christ our Lord" (Romans 6:23).

Drawing on these scriptures and others, the Unam Sanctam claimed that, since no one is worthy of heaven, and the Church alone, with the pope as its head, can provide salvation, even kings were to submit completely to the pope. The nobility rejected the bull and it was largely ignored, allowing the monarchy to continue to rule without papal interference. The Unam Sanctam is regarded as one of the most direct attempts of the medieval Church to assert control over temporal affairs.

Authority of the Church

One of the early appeals of Christianity was direct communion with God through Jesus Christ. Christ, as Paul makes clear to the Athenians in the Book of Acts, was everywhere. One could speak to Christ from one's hearth, walking down the street, or in a congregation of like-minded believers, but one did not need to go to a temple or sacred grove and make a sacrifice to be heard by the divine. God, through the intercession of Jesus Christ, was always listening.

After the Church was legitimized by Constantine the Great (r. 306-337) in the 4th century, developing into a powerful political and social entity, God was no longer accessible unless one was a member in good standing. To be such a member, one needed to observe the Church's teachings. Paul's admonitions in the Book of Romans and elsewhere on the sinful nature of humanity and the necessity of salvation, coupled with the human fear of death, made the Church – God's representative body on earth – an absolute necessity. A sinful individual, unschooled in Church doctrine, had no hope of understanding the will of God or the meaning of the scriptures and required the intercession of a priest.

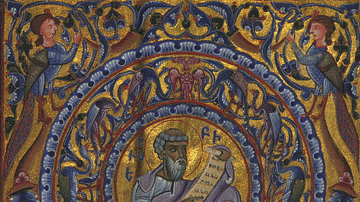

The parish priest derived his power from the Church hierarchy above him going up through canons, legates, bishops, cardinals, to the pope – the successor to the apostle Saint Peter – and the only man on earth who could claim to speak for God. The pope's supreme power, however, did not always sit well with the European aristocracy and ruling class who noticed that God's will and the pope's self-interest were often curiously combined.

While continuing to point out its own vital necessity to the population at large, the papacy recognized it needed some hard-hitting evidence to convince stubborn monarchs to comply with its wishes. The Church required some temporal authority to substantiate its claim to spiritual authority even over a monarch but also needed to make clear that it was only through total submission to the Church that one could expect salvation from hell. Two documents from the Middle Ages served this purpose, one was The Donation of Constantine and the other, the Unam Sanctam ("One Holy Church"), considered the ultimate claim of the absolute spiritual authority of the Catholic Church.

The Donation of Constantine

The Donation of Constantine was a document claiming that Constantine the Great, who had legitimized Christianity, had "donated" his authority to the Church in gratitude for being cured of leprosy through sincere conversion and baptism by Pope Sylvester I (served 314-335). The document made clear that Constantine's power as emperor afterwards derived from the Church, and it was used by popes to coerce European rulers into complying with the Church's agenda.

The first use of The Donation of Constantine is thought to have been just after the rise to power of Pepin the Short, King of the Franks (r. 751-768). Pope Zachary (served 741-752) hoped to control the new king and the lands of the Franks but died shortly after Pepin was installed. His successor, Pope Stephen II (served 752-757), following the same agenda, is thought to have used the document to prove the Church's sovereignty even over sovereigns.

Since the Church gave a king his power, the Church could just as easily take it away. Pepin the Short, who was illiterate and would not have known what the document said, never mind whether it was legitimate, responded with The Donation of Pepin, a large land grant to the papacy of regions he had recently conquered from the Lombards. The Donation was also used by Pope Adrian I (served 772-795) to coerce Charlemagne (l. 742-814) into following his father's example and granting lands to the Church. Charlemagne simply ignored the request, however.

The document was a forgery, most likely made under the direction of Pope Stephen II, but no one would know this until the 15th century. Even though monarchs throughout the Middle Ages contested the document, they had no resources to even attempt to prove it was fake. The scholar and priest Lorenzo Valla (l. c. 1407-1457) proved it was a forgery through a careful evaluation of the text c. 1439-1440 in which he demonstrated that the language used was not consistent with that of 4th-century Rome but could be dated with certainty to the 8th century, the time of Stephen II and Pepin the Short.

The Unam Sanctam

The Donation made it clear that monarchs owed their power to the papacy, but a king, even while respecting Constantine for his legacy, might still question why the Church and the papacy were deserving of such an honor - or of any honor – at the expense of a sitting monarch. Between 1296-1302, one king – Philip IV of France (r. 1285-1314) – did just that when he decided to tax the clergy in defiance of traditional policy. Pope Boniface VIII reacted with a papal bull forbidding the clergy paying the king anything without papal approval. Philip IV responded with an embargo which effectively cut the papacy off from significant sources of revenue.

The feud between the pope and the king continued until, in 1302, Boniface VIII issued the Unam Sanctam, which reads:

Urged by faith, we are obliged to believe and to maintain that the Church is one, holy, catholic, and also apostolic. We believe in her firmly and we confess with simplicity that outside of her there is neither salvation nor the remission of sins, as the Spouse in the Canticles [Sgs 6:8] proclaims: 'One is my dove, my perfect one. She is the only one, the chosen of her who bore her, 'and she represents one sole mystical body whose Head is Christ and the head of Christ is God [1 Cor 11:3]. In her then is one Lord, one faith, one baptism [Eph 4:5]. There had been at the time of the deluge only one ark of Noah, prefiguring the one Church, which ark, having been finished to a single cubit, had only one pilot and guide, i.e., Noah, and we read that, outside of this ark, all that subsisted on the earth was destroyed.

We venerate this Church as one, the Lord having said by the mouth of the prophet: 'Deliver, O God, my soul from the sword and my only one from the hand of the dog.' [Ps 21:20] He has prayed for his soul, that is for himself, heart and body; and this body, that is to say, the Church, He has called one because of the unity of the Spouse, of the faith, of the sacraments, and of the charity of the Church. This is the tunic of the Lord, the seamless tunic, which was not rent but which was cast by lot [Jn 19:23- 24]. Therefore, of the one and only Church there is one body and one head, not two heads like a monster; that is, Christ and the Vicar of Christ, Peter and the successor of Peter, since the Lord speaking to Peter Himself said: 'Feed my sheep' [Jn 21:17], meaning, my sheep in general, not these, nor those in particular, whence we understand that He entrusted all to him [Peter]. Therefore, if the Greeks or others should say that they are not confided to Peter and to his successors, they must confess not being the sheep of Christ, since Our Lord says in John 'there is one sheepfold and one shepherd.' We are informed by the texts of the gospels that in this Church and in its power are two swords; namely, the spiritual and the temporal. For when the Apostles say: 'Behold, here are two swords' [Lk 22:38] that is to say, in the Church, since the Apostles were speaking, the Lord did not reply that there were too many, but sufficient. Certainly, the one who denies that the temporal sword is in the power of Peter has not listened well to the word of the Lord commanding: 'Put up thy sword into thy scabbard' [Mt 26:52]. Both, therefore, are in the power of the Church, that is to say, the spiritual and the material sword, but the former is to be administered for the Church but the latter by the Church; the former in the hands of the priest; the latter by the hands of kings and soldiers, but at the will and sufferance of the priest.

However, one sword ought to be subordinated to the other and temporal authority, subjected to spiritual power. For since the Apostle said: 'There is no power except from God and the things that are, are ordained of God' [Rom 13:1-2], but they would not be ordained if one sword were not subordinated to the other and if the inferior one, as it were, were not led upwards by the other.

For, according to the Blessed Dionysius, it is a law of the divinity that the lowest things reach the highest place by intermediaries. Then, according to the order of the universe, all things are not led back to order equally and immediately, but the lowest by the intermediary, and the inferior by the superior. Hence, we must recognize the more clearly that spiritual power surpasses in dignity and in nobility any temporal power whatever, as spiritual things surpass the temporal. This we see very clearly also by the payment, benediction, and consecration of the tithes, but the acceptance of power itself and by the government even of things. For with truth as our witness, it belongs to spiritual power to establish the terrestrial power and to pass judgement if it has not been good. Thus, is accomplished the prophecy of Jeremias concerning the Church and the ecclesiastical power: 'Behold to-day I have placed you over nations, and over kingdoms 'and the rest. Therefore, if the terrestrial power err, it will be judged by the spiritual power; but if a minor spiritual power err, it will be judged by a superior spiritual power; but if the highest power of all err, it can be judged only by God, and not by man, according to the testimony of the Apostle: 'The spiritual man judgeth of all things and he himself is judged by no man' [1 Cor 2:15]. This authority, however, (though it has been given to man and is exercised by man), is not human but rather divine, granted to Peter by a divine word and reaffirmed to him (Peter) and his successors by the One Whom Peter confessed, the Lord saying to Peter himself, 'Whatsoever you shall bind on earth, shall be bound also in Heaven' etc., [Mt 16:19]. Therefore whoever resists this power thus ordained by God, resists the ordinance of God [Rom 13:2], unless he invent like Manicheus [Mani, founder of Manichaeism] two beginnings, which is false and judged by us heretical, since according to the testimony of Moses, it is not in the beginnings but in the beginning that God created heaven and earth [Gen 1:1]. Furthermore, we declare, we proclaim, we define that it is absolutely necessary for salvation that every human creature be subject to the Roman Pontiff.

(Papal Encyclicals Online; Ross & Martin pp. 233-236)

The Unam Sanctam was issued 18 November 1302 and response to it was almost universal rejection among the European nobility. Philip IV had the renowned and controversial theologian, philosopher, and Dominican friar John of Paris (l. 1255-1306) write a refutation arguing that the Church did indeed have spiritual authority but not over temporal matters and certainly not over kings who ruled by divine right and so had clearly already been installed in power by God and required no further submission to papal whims.

Philip IV then accused Boniface of various crimes which he claimed he could prove and demanded he step down as pope. Boniface responded by drafting the excommunication of Philip IV, but before he could issue it, Philip IV sent 1,000 knights to attack Boniface in his palace and drag him back to Lyon for trial in September 1303.

Boniface was captured, beaten, and deprived of food and water for three days until he was rescued by local citizens loyal to him. Even so, his harsh treatment affected his health and he died a month later of fever in October 1303. Boniface VIII was succeeded by Clement V (served 1305-1314), a Frenchman, who sided with Philip IV and even moved his court to Avignon to please the king.

The excommunication of Philip IV was dropped, and Clement V instead issued a declaration clearing Philip of any guilt in the attack on Boniface. The Unam Sanctam was then ignored by the European nobility who sided with Philip IV and John of Paris in claiming that the Church had no power over temporal affairs and a monarch should be able to rule as he saw fit without fear of ecclesiastical interference or reprisals for failing to comply with papal demands.

Conclusion

The nobility's arguments were all sound but ultimately futile because logical and rational claims had no power against the seemingly self-evident truth that the Church alone had the power to unlock the gates of heaven for a soul, consign it to the suffering of purgatory, or condemn it to hell. A king might accept excommunication for some transgression but would ultimately have to come to some form of terms with the pope to have it lifted in order to continue to be regarded as a legitimate Christian monarch.

In the same way the papacy dealt with the monarchy, the Church in general operated with the common folk of the Middle Ages. From the 9th century onwards, the Church issued documents known as penitentials which served as a guide for clergy in prying into the private affairs of parishioners in order to enforce the proper practice of Christianity. Right practice reflected right belief – defined as orthodox Catholic belief – and those who were found deviating from acceptable practice could be accused of heresy. Improper practices included employing diviners to tell one's future, using incantations to ward off misfortune or bring luck, the use of charms and talismans, collecting medicinal herbs while chanting incantations instead of the Our Father, and criticizing Church policy, among many others.

Even though the Unam Sanctam did not have the effect Boniface was sure it would, it perfectly reflected the Church's view of itself as the only legitimate agent of salvation; a view it impressed on the population of Europe consistently along with the reality of the fires of hell awaiting transgressors after death. The Church's insistence on its unique position had already contributed to the so-called Great Schism of 1054 between the Roman Catholic Church in the west and the Eastern Orthodox Church as the medieval Church of Rome claimed it alone had received authority from Saint Peter and the eastern Church should surrender its autonomy.

In 1054, the Eastern Orthodox Church refused to comply in the same way that Philip IV of France refused in 1302 and, eventually, as the men who led the Protestant Reformation of the 16th century would do also. The spiritual authority of the Church was finally compromised, however, not by critics' refutations but by its own internal failings which provoked such reactions. Many of the policies and practices of the Church clearly contradicted the idealized vision it had of itself and its role in saving the souls of those it claimed to serve and this would eventually contribute to its fracture during the Protestant Reformation.