The Mongol invasions of Japan took place in 1274 and 1281 CE when Kublai Khan (r. 1260-1294 CE) sent two huge fleets from Korea and China. In both cases, the Japanese, and especially the samurai warriors, vigorously defended their shores but it would be typhoon storms and the so-called kamikaze or 'divine winds' which sank and drowned countless ships and men, thus saving Japan from foreign conquest. The whole glorious episode, which mixed divine intervention with martial heroism, would gain and hold mythical status in Japanese culture forever after.

Diplomatic Opening

The Mongols had already sucked half of China and Korea into their huge empire, and their leader Kublai Khan now set his sights on Japan. Kublai was the grandson of Genghis Khan and had founded the Yuan dynasty of China (1271-1368 CE) with his capital at Dadu (Beijing), but just why he now wanted to include Japan in his empire is unclear. He may have sought to conquer Japan for its resources. The country did have a long-standing reputation in East Asia as a land of gold, a fact recounted in the West by the Venetian traveller Marco Polo (1254-1324 CE). Kublai Khan may have wished to enhance his prestige or eliminate the trade between that country and his great enemy in southern China, the Southern Song Dynasty (1125-1279 CE). The conquest of Japan would also have brought a new and well-equipped army into the Khan's hands, which he could have used to good effect against the troublesome Song. The invasions may even have been some sort of revenge for the havoc that the wako (Japanese pirates) had been causing to East Asian coastlines and trade ships. Whatever his reasons, the approach was clear: diplomacy first, warfare second.

The Great Khan sent a letter to Japan in 1268 CE recognising its leader as the 'king of Japan' and expressing a desire to foster friendly relations but also demanding tribute be paid to the Mongol court with the ominously veiled threat that the use of arms was, the Khan hoped, to be avoided. A Chinese ambassador, Zhao Liangbi, was also sent to Japan in 1270 CE, and he stayed there for a year to foster some sort of understanding between the two nations. Further letters and ambassadors were sent by the Khan up to 1274 CE, but all were blatantly ignored as if the Japanese did not quite know how to respond and so decided to sit silently on the diplomatic fence.

The Kamakura Shogunate had ruled Japan since 1192 CE, and the regent shogun Hojo Tokimune (r. 1268-1284 CE) was confident he could meet any threat from mainland Asia. Troops were put on alert in the Dazaifu fortress and military base in northwest Kyushu where any invasion seemed most likely to land, but the Khan's diplomatic approach was rebuffed both by the Japanese emperor and the shogunate. The lack of subtlety in the Japanese response to the Khan's overtures may have been down to their lack of experience in international relations after a long period of isolation and by the bias of their principal contact with mainland Asia, the Southern Song, and the low opinion exiled Chinese Zen Buddhist monks had of their Mongol conquerors.

The First Invasion (Bunei Campaign)

The Khan amassed a fleet of some 800-900 ships and dispatched it from Korea to Japan in early November 1274 CE. The ships carried an army of some 16,600-40,000 men, which consisted of Mongols and conscripted Chinese and Koreans. The first Japanese territory to receive these invaders was Tsushima and Iki Islands on 5 and 13 November respectively, which were then plundered. The Mongol attacks had met stiff resistance on Tsushima, where the defenders were led by So Sukekuni, but were successful largely thanks to superior numbers. The defensive force at Iki, led by Taira Kagetaka, was equally valiant, but they were eventually obliged to make a last stand within Hinotsume castle. When no reinforcements came from the mainland, the castle fell.

After a brief stop at Takashima Island and the Matsuura peninsula, the invasion fleet proceeded to Hakata Bay, landing on 19 November. The large bay's sheltered and shallow waters had suggested to the Japanese this would be the exact spot chosen by the Mongol commanders. Prepared they may have been, but the total Japanese defence force was still small, between 4,000 and 6,000 men.

The Mongols won the first engagements thanks to their superior numbers and weapons - the powerful double-horn bow and gunpowder grenades fire by catapults - and their more dynamic battlefield strategies using well-disciplined and skilful cavalry which responded to orders conveyed by gongs and drums. The Mongols had other effective weapons, too, such as armour-piercing crossbows and poisoned arrows. In addition, the Japanese were not used to combat involving mass troop movements as they favoured allowing individual warriors to pick their own single targets. Rather, the Japanese warriors operated in small groups led by a mounted samurai skilled at archery and a number of protective infantry armed with a naginata or curved-blade pole-arm. Another disadvantage was that the Japanese tended to use shields only as protective walls for archers while the Mongols and the Korean infantry typically carried a shield of their own as they moved around the battlefield. The samurai did have certain advantages over the enemy as they wore iron-plate and leather armour (only the Mongol heavy cavalry wore armour) and their long sharp swords were used much more effectively than the Mongol short sword.

Curiously, 18 days after first landing on Japanese soil and despite creating a bridgehead at Hakata Bay, the invaders did not push on deeper into Japanese territory. Perhaps this was because of supply problems or the death of the Mongol general Liu Fuxiang, killed by a samurai's arrow. It may also be true that the whole 'invasion' was actually a reconnaissance mission for the second larger invasion yet to come and no conquest was ever intended in 1274 CE. Whatever the motive, the invaders remained by their ships for the night, withdrawing out into the bay for safety on 20 November. This was a fateful decision because, in some accounts, a terrible storm then struck which killed up to a third of the Mongol army and severely damaged the fleet. The attackers were thus obliged to withdraw back to Korea.

Diplomatic Interval

Kublai Khan then returned to diplomacy and sent another embassy to Japan in 1275 CE demanding, once again, tribute be paid. This time the shogunate was even more dismissive in its reply and beheaded the Mongol ambassadors on a beach near Kamakura. The Khan was undeterred and sent a second embassy in 1279 CE. The messengers met the same fate as their predecessors, and the Khan realised only force would bring Japan into the Mongol Empire. However, Kublai Khan was occupied with campaigns in southern China against the Song, and it would be two more years before he turned his attention once again to Japan.

Meanwhile, the Japanese had been expecting an imminent invasion ever since 1274 CE, and this period of high suspense made a great dent in the government's treasury. Apart from keeping the army on standby, fortifications were built and massive stone walls erected around Hakata Bay in 1275 CE which measured some 19 kilometres (12 miles) in length and were up to 2.8 metres (9 ft) high in places. Intended to permit archers on horses, the inner sides of the Hakata walls were sloped while the outer facing was sheer. If a second invasion was to come, Japan was now much more prepared for it.

The Second Invasion (Koan Campaign)

Kublai Khan's second invasion fleet was a whole lot bigger than the first one. This time, thanks to his recent defeat of the Song and acquisition of their navy, there were 4,400 ships and around 100,000 men, again a mix of Mongol, Chinese, and Korean warriors.

Once again, the invaders hit Tsushima (9 June) and Iki (14 June) before attacking Hakata Bay on Kyushu on 23 June 1281 CE. This time, though, the force split and one fleet attacked Honshu where it was rebuffed at Nagato. Meanwhile, at Hakata, the Japanese put their defences to good use and presented a stiff resistance. The fortification walls did their job, and this time the attackers could not establish themselves permanently on the beach, resulting in much shipboard fighting. Eventually, after heavy losses, the Mongols withdraw first to Shiga and Noki Islands and then to Iki Island. There they were harassed by Japanese ships making constant raids into the Mongol fleet using small boats and much courage. Many of the later stories of samurai heroics come from this episode of the invasion.

The Khan then dispatched reinforcements from southern China, perhaps another 40,000 men (some sources go as high as 100,000), and the two armies gathered to make a combined push deeper into Japanese territory, this time selecting Hirado as the target in early August. The combined fleets then moved east and attacked Takashima, the battle there taking place on 12 August.

Fierce fighting raged for several weeks and the invaders likely faced shortages of supplies. Then, yet again, the weather intervened and caused havoc. On 14 August a typhoon destroyed most of the Mongol fleet, wrecking ships that had been tied together for safety against Japanese raids and smashing the uncontrollable vessels against the coastline. From half to two-thirds of the Mongol force was killed. Thousands more of the Khan's men were washed up or left stranded on the beaches of Imari Bay, and these were summarily executed, although some Song Chinese, former allies of Japan, were spared. Those ships that survived sailed back to China.

The storm winds that either sunk or blew the Mongol ships safely away from Japanese shores were given the name kamikaze or 'divine winds.' as they were seen as a response to the Japanese appeal to Hachiman, the Shinto god of war, to send help to protect the country against a vastly numerically superior enemy. The name kamikaze would be resurrected for the Japanese suicide pilots of the Second World War (1939-1945 CE) as they, too, were seen as the last resort to once again save Japan from invasion.

It seems, too, that the Mongol ships were not particularly well-built and so proved much less seaworthy than they should have been. Modern marine archaeology has revealed that many of the ships had especially weak mast steps, which is something absolutely not to have in the case of a storm. The poor workmanship may have been due to Kublai Khan rushing to get the invasion fleet together as many of the ships in the fleet were of a variety without a keel and highly unsuitable for sea voyages. Further, Chinese ships of the period were actually renowned for their seaworthiness, so it seems the demand for a huge fleet in a short space of time resulted in a risk that did not pay off. Nevertheless, the crucial factor in the fleet's demise was the Japanese attacks which had forced the Mongol commanders to have their large and unwieldy ships lashed together using chains. It was this defensive measure which proved fatal, come the typhoon.

Aftermath

The Mongols would also fail in their attempts to conquer Vietnam and Java, but after 1281 CE, they did then establish a lasting peace over most of Asia, the Pax Mongolica, which would endure until the rise of the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644 CE). Kublai Khan never gave up on the diplomatic route either and continued to send unsuccessful missions to persuade Japan to join the Chinese tribute system.

The Japanese, meanwhile, may have seen off the two invasions they called Moko Shurai but they fully expected a third to come at any time and so kept an army in constant readiness for the next 30 years. Fortunately, for them, the Mongols had other challenges to face along the borders of their massive empire and there would be no third time lucky in the attempt to conquer Japan. The great significance of the invasions to the Japanese people is here summarised by the historian M. Ashkenazi:

For the Japanese of the thirteenth century, the threatened Mongol invasion was, historically, and politically, a major watershed. It was the first time the entire military might of Japan had had to be mobilized for defence of the nation. Until then, even foreign wars were little more than squabbles that involved one or another faction within Japan - essentially domestic affairs. With the Mongol invasion, Japan became exposed to international politics at a personal and national level as never before. (188-9)

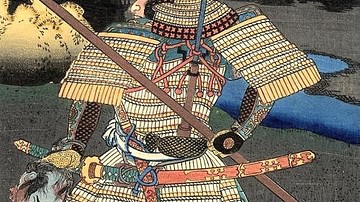

The Buddhist monks and Shinto priests who had long been promising divine intervention were proved right when the storms destroyed the Mongol fleets, and this resulted in an upsurge in both religions' popularity. One area of life where the invasions are curiously absent is in Japanese medieval literature but there is one famous scroll painting depicting the invasion. Commissioned by a samurai warrior who fought during the invasion, Takezaki Suenaga, it is known as the Mongol Scroll (Moko Shurai Ekotoba) and was produced in 1293 CE to promote Takezaki's own role in the battle.

Unfortunately for the Japanese government, though, the practical costs of the invasions would have serious consequences. An army had to be kept in constant readiness - Hakata was kept on alert with a standing army until 1312 CE - and payment to soldiers became a serious problem leading to widespread discontent. This was a war of defence not conquest and there were no spoils of war like booty and land to reward the fighters. The agricultural sector was also severely disrupted by the defence preparations. Rivals to the Hojo clan, who ruled the Kamakura Shogunate, began to prepare their challenge to the political status quo. Emperor Go-Daigo (r. 1318-1339 CE), eager for the emperors to regain some of their long-lost political power, stirred up a rebellion which resulted in the eventual fall of the Kamakura Shogunate in 1333 CE and the installation of the Ashikaga Shogunate (1338-1573 CE) with its first shogun Ashikaga Takauji (r. 1338-1358 CE).

This content was made possible with generous support from the Great Britain Sasakawa Foundation.