Defining Thracian art is a difficult task due to the fact that what we call today Thrace was never a single unified state but, rather, a collection of many independent communities (or tribes) who formed both alliances and rivalries with each other over time. These tribes, although collectively called 'Thracians' by the Greeks and Romans, never thought of themselves as a unified community and differed from each other. Furthermore, Thrace was geographically situated on а crossroad between Europe and Asia, and its cultural and political development was subject to continuous alterations and foreign influences.

A substantial amount of the artefacts in the Thracian archaeological record comes from diverse cultural and stylistic traditions. Seemingly, such objects have been produced in various workshops all over the ancient world from the pre-Achaemenid Middle East to Asia Minor and Classical Greece. The Thracian elite highly appreciated foreign luxuries and their tombs and graves were packed with imported pieces. Some of these objects were passed down in families for generations. Most of the artefacts were brought by foreign delegations in the form of diplomatic gifts to the local Thracian tribal chiefs. The luxury items made out of precious metals had a universally accepted monetary value and thus were the currency of choice utilised by visiting foreign envoys when trying to accomplish a political objective. The reasoning behind the seemingly one-sided gesture of gift giving varied but mainly revolved around gaining geopolitical favour of often a military character or facilitating trade.

Achaemenid & Achaemenid-inspired Vessels in Thrace

A great deal of Achaemenid and Achaemenid-inspired drinking vessels made of bronze and precious metals are continuously found in Thracian graves and tombs. According to Herodotus' writings, which are considered the primary source of information on the subject, the Achaemenid presence in European Thrace began in the late 6th century BCE (c. 513 BCE) when King Darius the Great launched his campaign against the Scythians and marched with his Persian army through Eastern Thrace up to the Istros River (Danube) and it continued during the Greco-Persian wars (499-449 BCЕ). After the wars, Anatolia remained Achaemenid territory and contacts between the European Thracians and the Persians continued until c. 400 BCЕ.

Artefacts similar in style to those in the Middle East were manufactured in Thrace before the Persians' arrival. Such items include bronze zoomorphic figures and miniature axes dating from 8th-7th century BCE in which pre-Achaemenid traces can be seen. Shallow bowls and mesomphalos phialae, shapes likely originated in Assyria from where they spread to the west, are also found on Thracian territories. The earliest phialae in Thrace resemble the bronze cups from Gordion, Phrygia. However, the rise in popularity of phialae made of precious metals used in Thrace coincided with the Persian appearance in the North Aegean, and its boom was in the 4th century BCE.

Even though oriental influences had been felt before the Achaemenids invaded the Balkans, the period of a constant close encounter, interaction, diplomatic and commercial exchange with the Achaemenid Empire for more than a century does appear to have left a detectable mark on Thracian culture. The Achaemenid presence in Thrace likely played a key role in the formation of the Odrysian kingdom at the end of the 6th century BCE, which was to become the most powerful Thracian polity in antiquity. The exact date of its foundation by the King Teres (known as Teres I), according to Thucydides, cannot be determined, but Herodotus claims that his first diplomatic interactions with the Scythians (Hdt. 4.80) can probably be dated in the second quarter of the 5th century BCE, and the beginning of the kingdom can possibly be placed in the late 6th century BCE. The military strength of the Achaemenid campaign was formidable, and the implications to the sovereignty of any tribes or empires that stood in their way were significant. This political reality has possibly played a key factor in the partial unification of the Thracians.

Elite Drinking & Dining

The Odrysians likely became a key provider of supplies for the Persian military force. This probably led to the Thracians familiarising themselves with and adopting some Achaemenid practices in the sphere of politics and administration, and it also introduced them to how the Persians emphasised their aristocratic standing in the society. However, the more profound reason for the Achaemenid influence upon Thrace was the similarity between Persian and Thracian society: a similar structure of a ranked society ruled by aristocrats. Thracian paradynastes resembled Persian satraps. Odrysian kings ruled from fortified residences, not unlike the several capitals of the Achaemenids.

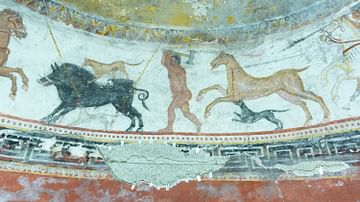

Similar to the Achaemenids, the Thracian elite practised dining and drinking from gold and silver tableware during formal banquets and religious ceremonies. Aside from being a social gathering, the symposium was also a widespread form of communication in antiquity. The majority of Achaemenid or Achaemenid-inspired imports were likely used in such parties. The drinking vessels were part of widely-distributed series of 'exotic' goods which were primarily associated with the Persian taste.

A very good example of such oriental Achaemenid-style vessel is the amphora rhyton from Kukouva Mogila tumulus, from the necropolis of Duvanlii, South Bulgaria (early 5th century BCE). This shape, with zoomorphic handles and a spout, is represented on the Apadana reliefs sculptures in Persepolis as part of the tributes brought to the king, in the hands of the gift-bearers, as well as in the wall-paintings of the Karaburun tomb in Lycia. The vase's shape, decoration, and style are truly Persian in character. Other similar examples are the amphorae from the George Ortiz collection (5th century BCE) and the Vassil Bojkov collection (c. 500 BCE), probably work of a Lydian workshop under Achaemenid influence. The gold amphora rhyton from the Panagyurishte treasure whose handles are shaped as centaurs can be considered a Hellenized successor of the same type of vessel.

Rhyta with an animal head or an animal forepart are clearly an Achaemenid type of vessel and examples of it made out of precious metal are today found in Bulgaria, in what used to be a Thracian inhabited territory. The silver-gilt bull rhyton with horizontal flutes on the horn (4th century BCE) from the Borovo treasure (near Ruse, Northeastern Bulgaria) bears a strong resemblance of such Iranian pieces. The rhyton, as a drinking vessel was a symbol of elite status, and its use in Thrace has a long-standing tradition. In his writings, Xenophon narrates about drinking horns filled with wine, being offered to the guests of the Odrysian King during banquets (Xen. Anab. 7.3.24). It is arguable whether the discovered pieces are Achaemenid imports because our knowledge of metal production in the Persian heartland is quite limited and most of the Achaemenid metal vessels come from peripheral areas of the empire where it is also possible they were produced by non-Persians workshops under the Achaemenid influence.

Gift Exchange

Typical Achaemenid phiale shapes, drinking cups, and bowls also found their way into the everyday life of local Thracian elites. They are the most common vessel shape depicted on the Persepolitan reliefs of the Apadana. Such forms were widely distributed in the eastern Mediterranean and were produced in metal, glass, and ceramic. Plenty of silver vessels of the same shape with a clear Persian origin have been found in Thracian burials. Some of the cups bear inscriptions with a personal name and a settlement name. According to some scholars such objects could be possessed by the king himself, marked the territory that he probably owned, and given to others as diplomatic gifts, served as propaganda.

The gift-giving tradition in Thrace was described by the ancient authors Thucydides and Xenophon. Thucydides states that tribute was presented to the Thracian king Sitalkes in the form of gold, silver, and other luxurious goods. He suggests that contrary to the Persian practice the Odrysians only received gifts and did not reciprocate them with gifts of their own (Thuc. 2.97. 3-4). Xenophon also describes the custom, where after a banquet the invited guests would offer gifts to the Odrysian king Seuthes without receiving gifts in return. However, the greater the gift they would present, the greater the king's favour would have been (Xen. Anab. 7.3.20). Overall the historical sources indicate that the Thracian practice around gift-giving did not differ significantly from that of the Persian or the Near Eastern royal protocol and similarly diplomatic gifts had the ultimate purpose of achieving a political objective such as hiring mercenaries or paying tributes.

Greek Influence & Imports in Thrace

The most evident Athenian presence in Thrace was between the mid-6th and the mid-4th century BCE, where Athenians recognised the importance of two Thracian regions; the Thracian Chersonese, which offered suitable land for settles but also served as the gateway to Hellespont and played a key role in maintaining control of the Black Sea trade, and the lower Strymon river valley, which secured a steady supply of timber and precious metals that were vital for the prosperity of the naval empire. The Aegean coast had been of great interests for the Greeks since a very early date. For instance, the ancient poet Homer knew only Thrace along the Aegean coast. Although Greeks occupied mainly the coastal areas of the Aegean and Black Sea and Thracians were concentrated inland, the two cultures were in constant interaction with each other. Various archaeological finds confirm the Thracian presence in the peripheral areas inhabited by Greeks. The ongoing contact between the Greeks and their inland Thracian neighbours resulted in a long process of cultural exchange and hybridisation of two separate cultures.

During the Peloponnesian War, the diplomatic relations between the two cultures were further strengthened, when Athenians made extensive use of Thracian mercenaries. They forged an alliance with the Odrysian king Sitalkes, who was already established as a most wealthy and powerful leader and had an enormous military capacity of soldiers and cavalry at his disposal. This extensive process of military and cultural interaction naturally resulted in many luxurious Greek objects ending up in Thracian territories, most likely as diplomatic gifts that would serve an agenda.

Greek imports were usually splendid objects from expensive materials such as bronze and precious metals that were certainly intended to showcase the elite status of their owner. Some of the archaeological finds reflect direct connections with Greek centres of production, Athens, among others. Most common are the typical Greek shapes such as hydriai, kylikes, kantharoi, phialae, and others, but exotic shapes such as metal rhyta are also present, some of them exclusively found in Thrace. Arguably, some scholars suggest that the primary purpose of such expensive imports was as a form of payment, considering their value in precious metal. Weights numbers are sometimes inscribed on some of the vessels, which gives further strength to the theory that silver vessels were also monetary instruments. However, their aesthetic value must have also been taken into consideration.

Rhyta were used in the Aegean world (notably in Attica), but predominantly in ceramic. In Thrace, the metal rhyta are usually of Greek origin, however, in Greece itself, there is no evidence for metal rhyta use, which implies that such vessels were solely made for foreign recipients such as Thracians, Scythians, Macedonians, etc. The silver rhyton with a goat protome (420-410 BCE) from Vassil Bojkov collection, found in Thrace, is likely made in a workshop somewhere in the Northern Aegean under Athenian influence. It represents a famous version of the Orpheus myth, where he is being killed by jealous Thracian women. A similar scene is presented on the silver kantharos from the Vassil Bojkov collection (420-410 BCE). There are artefacts with iconographic scenes, closely related to the Thracian culture and perception. Well known in Greek mythology as Thracian hero and musician, Orpheus must have been an easily recognisable figure, for its recipient. Naturally, the choice of gift was intended to impress and to show the goodwill and intentions of the givers, so some symbolic value must have been in favour.

The silver rhyton with a reclining Silenus (late 3rd or early 2nd century BCE) also represents a recognisable iconography for the Thracian culture. A Silenus is adorning the lower part of the rhyton, depicted lying on a panther skin and on a wineskin, where the top of the horn is decorated with gilded plants. The shape of the vase and the iconography that represents are closely related to the Dionysian cult, which was also worshipped in Thrace. This unique piece is probably the work of an Attalid workshop. The Attalids were a Hellenistic dynasty that ruled the city of Pergamon in Asia Minor. Written evidence points to the presence of Thracian mercenaries in the Attalid army, and further sources confirm a Thracian presence in some Attalid villages, which offers speculation on how this unique vessel may have found its way into Thrace.

Conclusion

The strategic location of Thrace has placed it on the crossroads of powerful neighbouring empires over the ages. Extensive military and diplomatic collaboration meant often inhabiting the same lands and closely interacting with each other in both political and social capacity. The extensive archaeological finds of luxurious metal vessels with Achaemenid and Greek origins or workshops under their influence in what used to be Thracian lands is a clear indication that the finely crafted objects were a common method of transacting by the Thracian rulers. While some of the finds can easily be dismissed as war booty, there is a significant amount of archaeological evidence that many of the splendid metal objects were presented as diplomatic gifts to pursue political favour, as a form of payment for military assistance, paying tributes or to state a claim on particular land. The luxurious metal objects seem to have been instrumental in navigating the complex relationships between Thrace and its neighbours, and they underline one of the ways foreign leaders managed to stay in the good grace of the Thracian kings.