Daily life in medieval Japan (1185-1606 CE) was, for most people, the age-old struggle to put food on the table, build a family, stay healthy, and try to enjoy the finer things in life whenever possible. The upper classes had better and more colourful clothes, used expensive foreign porcelain, were entertained by Noh theatre and could afford to travel to other parts of Japan while the lower classes had to make do with plain cotton, ate rice and fish, and were mostly preoccupied with surviving the occasional famine, outbreaks of disease, and the civil wars that blighted the country. Still, many of the cultural pursuits of medieval Japan continue to thrive today, from drinking green tea to playing the go board game, from owning a fine pair of chopsticks to remembering ancestors every July/August in the Obon festival.

Society

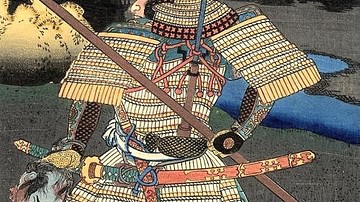

Japanese medieval society was divided into classes based on their economic function. At the top was the warrior class of samurai or bushi (which had its own internal distinctions based on the feudal relationship between lord and vassal), the land-owning aristocrats, priests, farmers and peasants (who paid a land tax to the landowners or the state), artisans and merchants. Curiously, the merchants were considered socially inferior to farmers in the medieval period. There were, too, a number of social outcasts which included those who worked in messy or 'undesirable' professions like butchers and tanners, actors, undertakers, and criminals. There was some movement between the classes such as peasants becoming warriors, especially during the frequent civil wars of the period, but there were also legal barriers to a member of one class marrying a member of another.

Although women were not given the advantages awarded to men, their status and rights changed through the medieval period and often depended on both the status of their husbands and the region in which they lived. Rights related to inheritance, property ownership, divorce, and freedom of movement all fluctuated over time and place. A common strategy of families everywhere and of all classes was to use daughters as a tool to marry into a higher-status family and so improve the position of her own relations. Another strategy was for powerful samurai to use their daughters as a means to solidify alliances with rival warlords by arranging marriages of convenience for them.

Marriage

Marriage was a more formal affair amongst the upper classes, while in rural communities things were more relaxed, even pre-marital sex was permitted thanks to the established tradition of yohai or 'night visit' between lovers. In ancient Japan, a married man often went to live in the family home of his wife, but in the medieval period, this was reversed. In the case of the wives of samurai, they were expected to defend the home in their husband's absence on campaign, and they were given the gift of a knife at their wedding as a symbol of this duty. Many such women did learn martial skills.

Divorce was always in favour of the male who could decide to terminate his marriage simply by writing a letter to his wife. If the couple remained on amicable terms, then a mutual settlement could be made, but the male ultimately had the power to decide such matters. If there were evidence of adultery, then the wife could even be executed. As a wife had no recourse to any legal protection, the only option for many women to escape adulterous or violent husbands was to join a convent.

The Family

The essential family unit in Japan was the ie (house) which included parents and their children, grandparents, other blood relations, and the household servants and their children. Eldest sons usually inherited the property of the ie, but the absence of male offspring could entail bringing in an outsider to act as head of the family (koshu) - male children were often adopted for this very purpose - although a female member might also take on the role, too. The wife of the koshu was the senior female in the family and was responsible for managing the household duties. The good of the ie was meant to take precedence over any individual's and the three principles to be followed by all were: obligation, obedience, and loyalty. For this reason, all the property within a family was regarded not as belonging to any individual but to the ie as a whole. Filial duty (oya koko) to one's parents and grandparents was especially cultivated as a positive sentiment.

Education

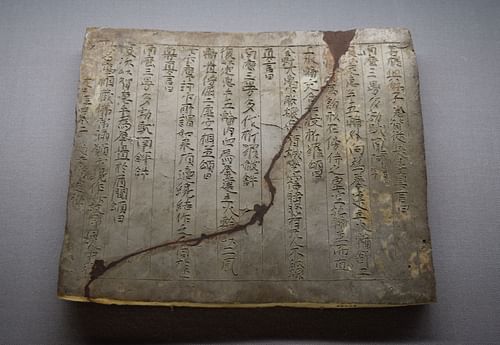

The children of farmers and artisans were taught by their fathers and mothers the practical skills they had acquired through a lifetime of work. Regarding more formal education, this had previously been the exclusive privilege of aristocratic families or those who joined Buddhist monasteries, but in the medieval period, the rising samurai class began to educate their children, too, largely at the schools offered by Buddhist temples. Nevertheless, the number of people who were literate, even in the upper classes, was only a tiny proportion of the population as a whole, and monks were much called on to assist with paperwork in the secular world.

When they did learn, children in the early medieval period did so from private tutors or the classes arranged by temples, but there was at least one famous school in the modern sense, the Ashikaga School, founded by the samurai Uesugi Norizane in 1439 CE and boasting 3000 students by the mid-16th century CE. Here, boys learnt the two subjects close to every warrior's heart: military strategy and Confucian philosophy. Many prosperous samurai also established libraries of classic Chinese and Japanese literature, which were made accessible to priests and scholars, and these often became noted centres of learning in the Edo period (1603-1868 CE). One famous example was the Kanazawa Library, established by Hojo Sanetoki in 1275 CE. Another source of education was the schools established by Christian missionaries from the 16th century CE.

Shopping

Markets developed in Japan from the 14th century CE so that most towns had a weekly or thrice-monthly one when merchants travelled around their particular regions and farmers sold their surplus goods. Foodstuffs were more available than ever before, increasing thanks to developments in agricultural techniques and tools. Goods were bartered for other goods, and coins were being used more and more (although they were actually imported from China). Markets were also promoted by local authorities who saw their value as a tax revenue source by standardising currencies, weights, and measures. Non-food items available at local markets included pottery, tools, cooking utensils, and household furniture. Markets at the capital and other larger cities might have more exotic goods on sale, such as Ming porcelain, Chinese silk, Korean cotton and ginseng, spices from Thailand and Indonesia, or Japanese-made jewellery and weapons.

Meals

In the medieval period, most upper-class Japanese and monks would have eaten two meals a day - one around noon and another in the early evening. Lower classes might have eaten four meals a day. Men generally ate separately from women, and there were certain rules of etiquette such as a wife should serve a husband and the eldest daughter-in-law should serve the female head of the household. Food was served on a tray placed in front of the diner who was seated on the floor. The food was then eaten with chopsticks made of lacquered wood, precious metal or ivory.

The influence of Buddhism on the aristocracy was strong and meant that meat was (at least publicly) frowned upon by many. The samurai and lower classes had no such qualms and consumed meat whenever they could afford to. The staple foods for everyone were rice (and lots of it - three portions per person per meal was not uncommon), vegetables, seaweed, seafood, and fruit. Soya bean sauce and paste were popular to give extra taste, as were wasabi (a type of horseradish), sansho (ground seedpods of the prickly ash tree), and ginger. Green tea was drunk, usually served after the food, but this was brewed from rough leaves and so different from the fine powder used in the Japanese Tea Ceremony. Sake or rice wine was drunk by everyone but was reserved for special occasions in the medieval period.

Clothing

Upper-class women wore perhaps the most famous wardrobe item from Japanese culture, the kimono. Meaning literally 'thing to wear', the kimono is a woven silk robe tied at the waist by a broad band or obi. Other clothes for both men and women of means tended to be silk, long and loose-fitting, and both sexes might wear baggy trousers, and women skirt-trousers, too. Women might wear a long robe with a train, the uchiki, while men wore short jackets called haori or the long jacket (uchikake or kaidori) fashionable from the Muromachi period (1333-1573 CE). From the Azuchi-Momoyama period (1568/73-1600 CE), men, especially samurai, often wore a matching sleeveless robe and trousers outfit called the kamishomo. Finer clothes were often beautifully embroidered with designs of plants, flowers, birds, and landscapes, which would become even more elaborate in the Edo period.

Lower classes typically wore similar clothes but of more sober colouring and made of woven flax or hemp and, if working in the fields in summer, both men and women often only wore a loincloth-type garment and nothing else. From the late 14th century CE cotton clothing became much more common for all classes. The preferred footwear for everyone was sandals (zori), made from either wood, rope, or leather. Country folk might wear straw boots (zunbe) in colder weather. The most common headgear was the kasa, a straw hat which took many forms, some of which indicated the wearer's social status.

A popular accessory for men and women was a hand fan (uchiwa) and specifically the folding fan (ogi) which became a status symbol. Women might wear an ornate comb or pin in their hair made from bamboo, wood, ivory or tortoiseshell and perhaps decorated with a few embellishments in gold or pearl. A pale complexion was admired on both men and women and so white powder (oshiroi) was worn. Fashionable women wore a red dot on their lower lip made using a flower-based paste or a red lipstick (beni). Women also shaved and redrew their eyebrows. Women and samurai were inclined to blacken their teeth in the medieval period in the process known as ohaguro. Although tattoos became fashionable in the 18th century CE, in medieval times they were used as a form of punishment for criminals - the actual crime being written on the face and arms for all to see.

Entertainment

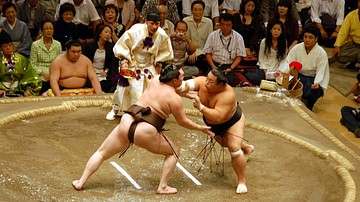

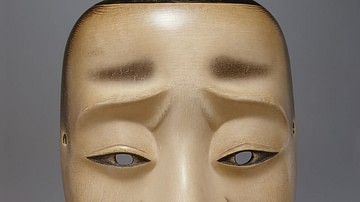

Medieval entertainments included sumo wrestling bouts, held at Shinto shrines before it gained a wider appeal in its own venues from the Edo period. Falconry, fishing, cock-fighting, a type of football game (kemari) where players had to keep the ball in the air as it went around a circle playing area, handball (temari), badminton (hanetsuki) which used wooden paddles, and martial arts (especially those involving horse riding, fencing, and archery) were popular pastimes. Indoor games included the two most popular board games: go and shogi. The game of go involves two players aiming to move white or black stones across a grid board in order to control territory while shogi is a form of chess. Cards were also played, although they were quite different to those in the west, with two popular sets having poems on them (karuta) or flowers and animals (hanafuda). Gambling was frequently associated with card-playing. From the 14th century CE, Noh theatre was another popular form of entertainment where masked actors performed in stylised movements set to music, telling the stories of celebrated gods, heroes, and heroines. Children played with the traditional toys popular elsewhere such as spinning tops, dolls, and kites.

Travel

Travel was restricted in the medieval period because of Japan's mountainous terrain and the lack of a well-kept road network. One group that did move around was pilgrims, although these were limited to those with either the means to pay for expensive travel arrangements or the time to do so. There were specific pilgrimage routes such as the 88-temple tour established by the monk Kukai (774-835 CE) and the 33-temple tour which worshippers of the Bodhisattva Kannon were encouraged to endure. Up to the Edo period, getting around was mostly done on foot, with goods carried by teams of horses or oxen pulling carts, while faster horses were ridden by messengers. Waterways were an important means to transport both people and goods, especially timber, cotton cloth, rice, and fish. The wealthy were carried about on a palanquin (kago) - a bamboo or wooden chair between long poles for the two carriers, one at either end. For the more adventurous there was maritime trade with both China and Korea, and monks, especially, travelled back and forth to study and bring ideas back to their monasteries. Both land and sea travel remained dangerous in medieval Japan, the former thanks to bandits and the latter due to the wako pirates that plagued the high seas.

Death & Funerals

Just as Japanese people today enjoy one of the longest life expectancy rates in the world, so, too in the medieval period the Japanese were ahead of almost everyone else. The average life expectancy was around 50 years of age (in the best locations and periods) compared to a high of 40 in Western Europe, for example. There remained challenges to overcome or avoid such as famine, vitamin deficiency from a rice-heavy diet, diseases such as smallpox and leprosy, illness caused by parasites which thrived in conditions where waste disposal was poor, and the risk of death or injury from wars. In the medieval period, the most common treatment of the dead was cremation (kaso).

When a person died, most Japanese thought that the spirit of the deceased then went to the 'Land of Darkness' or shigo no sekai. The spirts then might occasionally revisit the world of the living. Those who followed Buddhism believed that people either went to a form of hell or were reincarnated or went to the Buddhist paradise, the Pure Land. Ancestors were not forgotten and were honoured each year in the Obon festival held in July/August when it was thought they returned to their families for a three-day visit.

This content was made possible with generous support from the Great Britain Sasakawa Foundation.