Beginning approximately 2000 years ago, in a rugged stretch of southwestern Colombia where the Andes split into multiple ranges and the mighty Magdalena River is born, a people created a collection of magnificent ritual and burial monuments that form some of South America's most fascinating pre-Hispanic artifacts. Scattered across a region approximately 100 kilometers in diameter and encompassing active volcanoes, snow-capped peaks, and plunging valleys, these funerary sites are at their densest and most grand within the present-day municipalities of San Agustín and Isnos.

These monumental complexes contained single burials of important individuals within stone slab tombs covered with massive artificial earthen mounds. Most astonishingly, intricate megalithic statues were placed within and nearby many of the tombs and combine highly stylized human and animal characteristics to evoke the presence of surreal, almost hallucinatory beings.

These burial places formed the centers of small-scale chiefdoms and shared a set of sculptural motifs and styles, now collectively referred to as the "San Agustín style" given that the municipality is home to some of the most elaborate concentrations of monuments yet unearthed. While objects left behind provide insight into the characteristics of these ideologically advanced societies, without a written record and with the abandonment of sites in the region taking place before the arrival of the Spanish in the 16th century CE, the origins of and motivations behind these works have remained shrouded in mystery.

Mound-centered Societies

Peoples of this region referred to as the Upper Magdalena River Valley established agriculture, sedentary occupation, and the beginnings of complex societies at the turn of the 1st millennium BCE, making them one of the earliest pre-Hispanic societies to do so. During this time, huts and terraces began to appear on hilltops, ideal locations for sustenance agriculture given the area's high humidity, fertile volcanic soil, and tropical day length. Households were small and self-sufficient, composed of nuclear families burying their dead with simple offerings in shaft tombs dug near homes. These individual farmsteads were widely dispersed throughout the region; however, in certain areas, households began to cluster together perhaps to improve agricultural productivity, forming central places for early chiefdoms. At the beginning of our era, populations of these initial demographic centers began to increase, along with skill in the formation of lithic tools, ceramics, and gold ornaments.

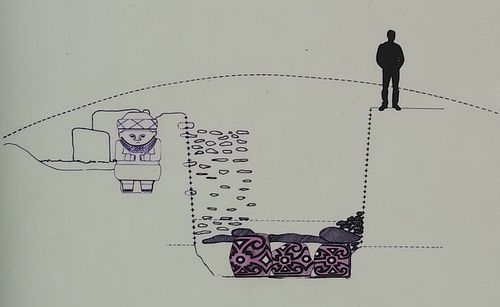

It was during this time, beginning c. 1 CE, that burial customs underwent a dramatic and labor-intensive shift. In addition to pre-existing shallow graves and shaft tombs, monumental funerary mounds with megalithic sculptures began to be constructed, likely by chiefs or other elite members of society to increase their prestige and spiritual power. These structures, built on artificially flattened hilltops near early household centers and connected in some cases by earthen embankments retained with stone walls, contained one or more tombs for single individuals. The body was placed in a wooden or stone sarcophagus before being surrounded by a dolmen-like burial chamber made of large vertical stone slabs supporting horizontal slabs above to form a corridor. Statues of supernatural beings carved out of stone were added, sometimes forming a part of the tomb itself but more commonly as stand-alone figures at the entrance of the corridor or nearby, as if to provide protection. Earth was then added over the top of this assemblage to form a mound up to 30 meters in diameter and four meters in height.

In some cases, statues were placed outside the mound, possibly to ward off would-be grave robbers. However, given the unusually large size of these figures (some are as tall as six meters) and the centrality and openness of the area around these complexes, it is likely that they formed ceremonial centers during the height of these chiefdoms. Such communal ceremonies, focused on monuments linking elite ancestors to mythical entities, would have reinforced a social hierarchy based on the prestige of these high-ranking individuals or more broadly on religious ideology as opposed to material wealth, given that relatively few items of value dating to this period have been uncovered within houses or as grave goods. The social and political importance of these funerary monuments is further emphasized by findings from a set of ancient population centers in San Agustín referred to as Las Mesitas. There, some of the most impressive mounds are tightly clustered with a high density of residential sites that contain artifacts indicating they belonged to higher-status families; ceramic decorations and ornaments of a rare type, and a higher ratio of serving to cooking vessels relative to sites at the periphery.

Mythical Beings

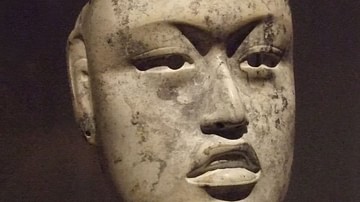

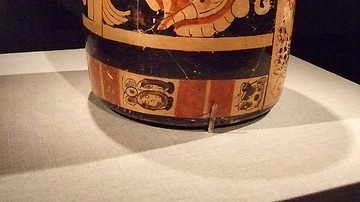

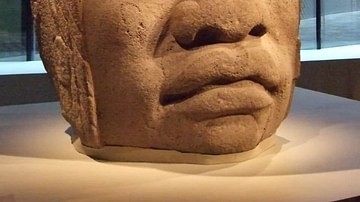

Over 500 megalithic statues created during this time and associated with ceremonial and burial sites have been identified across the Upper Magdalena Valley, making this the most extensive such pre-Hispanic grouping in South America. Sculpted out of soft volcanic rock using tools made of harder rock before being polished and finally painted in vivid colors, these figures take on many forms. Some were carved in the round and stand free while others were carved in relief in slabs or columns and sometimes form part of a tomb structure. The statues span the spectrum from realistic to abstract and from anthropomorphic to zoomorphic, with animals such as jaguars, monkeys, birds of prey, snakes, fish, frogs, and crocodiles recognizable. A majority are humanoid but with feline or simian features, most commonly displaying fanged teeth which are sometimes accompanied by a protruding snout, large outward-flaring nostrils, or almond-shaped eyes.

It is this seemingly partial transformation of human into beast, combined with outsize and spectacularly expressive faces and relatively diminished bodies (some lack a body altogether), that makes viewing these stone beings a surreal, otherworldly experience. The figures are nearly symmetric with straight sides and hunched shoulders, standing or sitting in a rigid front-facing pose, with arms and legs thin and close to the body, hands often together at the center of the body. Apart from these broad similarities, each character takes on its own unique and often peculiar personality. Some have the fierce expression of a warrior and carry one or more clubs; some have bulging eyes and mouths that in turns grimace and grin back at the viewer; others are more solemn with the large headdress, necklace, bracelets, and belt of a dignitary; others have swollen cheeks implying chewing of coca or swollen bellies implying fertility; while still others hold small animals, human infants, or various items with ceremonial connotations. Many statues additionally include what is referred to as an "alter ego" form — a typically bestial second figure that sits atop the head of a humanized one, possibly representing the wearing of a jaguar's pelt.

Some of the most notable sculptures include one referred to as El Partero, or "the midwife," a tall statue with two vertically opposed figures mated at the waist, the upper one dangling in its hands a potentially newborn human child. A second, known as El Doble Yo, takes the form of an anthropozoomorphic statue that combines a bottom figure displaying an even combination of human and feline traits and an upper alter ego form that is more bestial than human, with a crocodile-like creature portrayed as hanging off the back of both figures. Sculptures of crocodiles are also present in stand-alone naturalistic form in several tombs, an anomaly as neither crocodiles nor caimans are native to the region. Given that depressions in the mountainous landscape would have enabled communication with the northwestern reaches of the Amazon rainforest and the northern lowlands of Colombia where these animals reside, these statues are possible evidence of cultural contact or trade networks between chiefdoms of the Upper Magdalena region and distant peoples.

Clues to the conceptual inspirations of the sculptors can be found in the mythology and symbolism of contemporary indigenous peoples. Felines are widely renown for their strength and prowess as apex predators, and jaguars merging with or overpowering humans is a theme present in the origin stories of many Colombian tribes, some in the vicinity of the Upper Magdalena Valley. Shamanic themes of the transformation of humans into animals, the ability to take flight as potentially represented by avian headdresses, and the summoning of a protective animal spirit as potentially represented by alter ego forms are believed to be a part of the ritual activities of indigenous peoples throughout northern South America. Lending credibility to theories of cultural exchange, another potential thematic source comes from the Olmec civilization, flourishing in Mesoamerica beginning c. 1200 BCE, whose statuary is also characterized by large, expressive faces and also prominently features the human-jaguar transformation motif.

Not all carvings of the San Agustín style take the form of independent sculptures with funerary associations — at several remote sites, figures can be found carved in situ in volcanic rock formations. Most notable of these is La Chaquira, a set of human and animal figures appearing in poses possibly representing worship and carved into boulders overlooking a spectacular valley landscape through which the Magdalena River passes, 200 meters below. At another distinctive and likely ceremonial site, referred to as La Fuente de Lavapatas, sculptors modified a streambed to form complex new water channels and pools, along with carvings of mostly amphibian and reptilian figures.

A Change of Ways

After c. 900 CE, mortuary customs again mysteriously shifted: the construction of funerary mounds with statuary ceased, and important peoples were instead buried in shaft graves near homes as before, although with a higher number of ceramics and other items of wealth now included as offerings. As the population continued to increase, larger houses appeared and agriculture was intensified through the creation of complex drainage systems. Taken together, these changes represent an increasing role of economic factors over ideological ones as the basis of political power. Along with a shift in the style of ceramics, these changes leave open the possibility that the sculptural chiefdoms occupying the region before 900 CE were displaced or replaced by a new set of peoples with different skills and beliefs. After several centuries and possibly by the 14th century CE, evidence suggests these sites were finally abandoned, left to be swallowed by the lush jungle vegetation.

The Passage of Time

It is extraordinary to consider that Upper Magdalena peoples not only formed complex politically centralized societies in antiquity and in spite of the isolating terrain and far-flung population distribution but that they also had the resources and organizational ability necessary to create profound monumental architecture expressing and reinforcing their worldviews. Also remarkable is how well these complexes have weathered the centuries — those tombs which have been horizontally excavated reveal sarcophagi, slabs, and statues with readily discernible, intricately carved features. Even the multicolored mineral paints remain on many interior surfaces of tombs that were decorated with various geometric patterns, and on a select few statues well-shielded from the elements.

Known only to locals and a small number of travelers even after the Spanish reached the region in the 16th century CE, the existence of the monumental ruins did not become common knowledge until the first archaeological excavations in the early decades of the 20th century CE. Before this point, however, extensive looting had taken place. Grave robbers irretrievably altered the archaeological context, removing and selling to collectors what few gold ornaments were present along with smaller statues. Although the heads of some larger figures were stolen, the excellent state of preservation of many is undoubtedly related to their several ton weight which made removal impractical, allowing looted tombs to be reconstructed.

Other factors include restoration and preservation efforts which began in earnest in 1970 CE, around the time a large outlying site was added to an archaeological park now encompassing areas in San Agustín and Isnos. The soft volcanic rock making up these structures is susceptible to ground motion resulting from soil instability and earth tremors, chemical erosion caused by acids in rainfall and those produced by microorganisms, as well as mechanical erosion caused by wind and rain exposure; risks which have been partially mitigated by the addition of coverings. Many of the mounds remain unexcavated to limit their deterioration and are studied instead using non-invasive techniques. Declaration of the park as a National Monument of Colombia in 1993 CE and its inscription on the UNESCO World Heritage List two years later have furthered the case for continued preservation over competing land uses and drawn attention to stolen artifacts. Although conflicts periodically disrupted access to the region in the recent past, today for those curious enough to journey to the Upper Magdalena Valley these phenomenal artworks remain, ambassadors from an ancient and unknowable time.