The 8th November is celebrated as Archangels Day in Greece, but on that November day in 1977 CE something remarkable happened: an excavation team led by Professor Manolis Andronikos were roped down into the eerie gloom of an unlooted Macedonian-styled tomb at Vergina in northern Greece. Dignitaries, police, priests, and swelling ranks of archaeologists watched on in anticipation as the first shafts of light in 2,300 years penetrated its interior.

What emerged from beneath the great tumulus of soil was the 'archaeological find of the century' rivalling Howards Carter's discovery of Tutankhamun in the Valley of the Kings and Heinrich Schliemann's excavations at what he claimed to be 'Troy.' Inside the main chamber of the barrel-vaulted structure known as Tomb II lay gold and silver artefacts, exquisitely worked weapons and armour accompanied by invaluable grave goods which suggested the presence of royalty. Within a stone sarcophagus sat a never-before-seen gold chest containing carefully cremated bones wrapped in remnants of purple fabric. Andronikos proposed this was nothing less than Philip II of Macedon, father of Alexander the Great, who was stabbed to death in 336 BCE at Aegae, the nation's spiritual capital and burial ground of its kings.

For some onlookers the more significant discovery was the skeletal remains of a woman in the tomb's antechamber, resting in another gold ossuary; what the excavation team had found was a rare double burial. It was tempting to identify her as one of Philip's seven known wives. What complicated the hypothesis was the presence of a gold-encased Scythian bow-and-arrow quiver. Andronikos was vexed: “The problem created by the presence of a female burial and weapons is certainly strange ... she could have had some kind of 'Amazonian' leanings or familiarity with the weapons”(178). Here Andronikos was referring to the female warriors who featured prominently in ancient Greek legend and whose latter-day descendants were said to be Scythian female mounted archers.

Battle of the Bones

“Weapons were for men what jewels were for women,” reads a plaque in the Vergina Museum erected above the tombs in 1997 CE. Indeed, many commentators believed that the antechamber weapons belonged to the man next door, as their upright position against the door dividing the two chambers might indicate.

After a cluster of structures was uncovered under the same tumulus – named Tombs I to IV - there followed 35 years of controversy as historians and commentators argued the identifications of the Tomb II pair: Philip II and a wife, claimed one partisan camp; according to the opposition faction, they were Philip's half-witted son, crowned Philip III Arrhidaeus, and his young wife Adea-Eurydice. This tragic royal pair were executed together by Alexander's mother, Olympias, and thus they fitted the double burial scenario. Arguments became intricate, caustic, and divided the academic community, and there soon began a bitter “battle of the bones” waged through academic papers designed to shoot one another down (Grant 2020, 93).

What was arguably a case of archaeological gender bias attached to the antechamber weapons has since proved to be wrong. In 2013, an anthropological team studying the skeletal remains, led by anthropologists Professor Theo Antikas and Laura Wynn-Antikas, found a major shinbone fracture which had shortened the woman's left leg. This conclusively united the female with the armour, because the left shin guard or greave of a gilded pair, which had always looked rather feminine in proportion, was 3.5 cm shorter and also narrower than the right. That, in turn, linked the female to the weapons around her. Historians now had the conundrum of a limping warrioress with a precious artefact from the Scythian world. Moreover, closer analysis of her pubic bone aged her at 30-34 years at death, and that ruled out both the earliest and the most prominent of Philip's wives who were too old at his death, and also his final teenage bride, Cleopatra, as well as the equally young Queen Adea-Eurydice, the wife of his half-witted son.

The question remained: what was a Scythian artefact doing in a Macedonian tomb and could a link be found between the family of Alexander the Great and the Scythian world, or a female with 'Amazonian' leanings at least?

Amazons & Scythians

Amazons of legend and very real Scythian tribes were mentioned in the same breath in ancient Greece. The 5th-century BCE tragedian Aeschylus described them in Prometheus Bound as “The Amazons of the land of Colchis, the virgins fearless in battle, the Scythian hordes who live at the world's end,” while the rhetorician Isocrates termed them as “Scythians led by Amazons” in his Panegyric. In one of the many versions of the myths attached to these warrior women who inhabited the fringes of the Greek world, the tribes did indeed ally in the Attic War of legend, attempting to retrieve Antiope after her abduction by King Theseus, the hero who founded Athens. But it was Herodotus who explained how the fates of Amazons and Scythians became intertwined on the northern shores of the Black Sea where Greeks would settle to trade (4.110ff.).

Housebound Athenian women wistfully absorbed tales of legendary Amazons who ruled a gynocracy that rejected men. Formidable, sexually-liberated, single-breasted archers who dressed in britches and boots and roamed the plains on horses trained to kneel before them, Amazons were powerfully evocative of emancipation from strict Greek city-state laws. But did warrior women truly exist, because Herodotus was always regarded as a rather sensationalist historian?

In a series of recent excavations at burial mounds known as 'kurgans,' more than 112 graves of women buried with weapons were unearthed between the Don and the Danube rivers, 70 per cent of them between the ages of 16 and 30 at death. Many had bones scarred with arrow wounds while markers on their spines betrayed their lives on horseback. The high proportion of females and the weapons in their graves suggest 25 per cent of all Scythian fighters were women, a figure that appears to be rising with new DNA sexing of skeletal remains thought to be men. Some had unusually muscular right arms suggesting frequent use of a bow, while the single earring commonly accompanying them might have differentiated female fighters from the tribe's domestic women.

Legend claimed Scythians were descended from one of the three grandsons of Zeus; propitious golden gifts fell from heaven and signified which of them - the son of Heracles named Scythes - should rule the 'youngest of all the nations', forged just 1,000 years before Darius I crossed to Greece on the way to Marathon in 490 BCE. In Herodotus' day, the Scythians still wore belts with little cups attached commemorating their hero-ancestor; they were possibly used to carry the snake venom their arrows were dipped in, or for the swearing of blood-oaths in the saddle (Herodotus 4.3ff).

Scythians enjoyed just as fierce a reputation as their Amazon counterparts who, reported Herodotus, were absorbed into their race, and they had already driven out the Cimmerians from Ukraine and the Russian steppes long before his day. Herodotus described the Scythian scalping techniques in which the skin of the enemy was violently shaken from the skull and kneaded to make a rag to fasten to the bridle of their horse, while right arms of the enemy were skinned to make covers for arrow quivers (4.64.).

Scythians in the Greek World

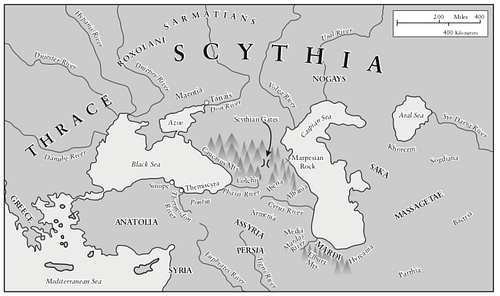

As they left no written records, we neither know their language nor whether Scythians had a written script, but their tribal regions stretched from the Danube around the northern reaches of the Black Sea to the borders of the Caspian. From there, the migratory lands swept east into modern Kazakhstan and the states to its south. 'Scythian' was therefore a loose appellation the Greeks provided to all Eurasian nomads sharing a common lifestyle in the swathe of land to the north of the Persian Empire; the Persians called them 'Saka' and the barren deserts they inhabited were apparently ridiculed in Greek proverbs.

Scythians had certainly entered the Greek cultural milieu long before Philip and Alexander. A Graeco-Scythian philosopher named Anacharsis is said to have travelled to Athens in the early 6th century BCE. Known for his candour and direct talk, he became acquainted with the great law-giver Solon and gained the rare privilege of Athenian citizenship. Another tradition cites Anacharsis as one of the Seven Sages of Greece who left a legacy of wise epithets behind.

Herodotus confirmed that Greeks and Scythians had coexisted around the region we associate with the eastern Crimea today. By 480 BCE, Greek settlers had established the federation of the Kingdom of Bosporus, driven by commerce and favourable trading conditions. Stonework in Scythian tombs suggests the Bosporan Greeks had built them, along with the conclusion that “the Scythian elite was highly Hellenised” (Tsetskhladze, 66). One thriving destination was the well-known metalworking centre of Panticapaeum, identified with modern Kerch on the Crimean Peninsula.

Graeco-Scythian art, like the Amazonomachy on the ivory-and-glass-encrusted ceremonial shield of the Tomb II male, with its hybrid imagery including Greeks battling with barbarians, had established itself in the region where these worlds overlapped and can still be seen on regional pottery. Neither should we forget the trade in slaves that saw captive Scythians shipped to Greece, Athens especially, where, paradoxically, a Scythian not-to-be-messed-with city police force emerged in the mid-5th century BCE.

The Vergina Tomb

The Vergina tomb conundrum remained unsolved. One early hypothesis favoured a presumed daughter of King Atheas of the Danubian Scythians, who at one stage planned an alliance with the Macedonian king by adopting Philip as his heir, despite having a son. The once-friendly relationship with Atheas broke down, but scholars conjectured that a daughter, given freely or taken with the 20,000 captive women in the wake of the briefly-enjoyed Macedonian victory, could then have become Philip's concubine or possibly his seventh wife of what would then be eight in total. But, as elegant as the hypothesis sounds, no daughter is ever mentioned in the ancient texts. Adopting Philip was rather a strange move if Atheas had a daughter, as the established method of forging an alliance with Macedon was to marry a young daughter to Philip at his polygamous court.

The Scythian daughter theory encounters more hurdles: Herodotus' colourful description (4.71ff.) of the Scythian pre-burial practice involved slitting open the belly of the deceased, cleaning it out and filling it with aromatic substances, after which the corpse was covered in wax before carting around for display to the tribe. In contrast, the Tomb II woman was cremated soon after death with no feminine adornments, where Scythian female burials were usually accompanied by jewellery: glass beads, earrings and necklaces of pearls, topaz, agate and amber, as well bronze mirrors and distinctive ornate bracelets. The Vergina mystery deepened.

More troublesome still for the all the proffered female identifications remained the unvoiced 'elephant in the room': ancient sources fail to mention the presence of any woman being cremated, prepared for ritual suicide, or entombed at Philip's funeral. And this suggests her burial in the second chamber took place after his, a hypothesis which correlated with what Andronikos observed when unearthing Tomb II: the main chamber and antechamber, with their different heights and roof-vault angles, looked to have been built in distinctly different stages.

Could the reign of Philip's son, Alexander, throw any light on the Tomb II warrioress? It was perhaps inevitable that tales of Amazons would enter the campaigns of Alexander who was determined to retrace the footsteps of prehistory's most colourful sagas. Alexander is said to have crossed the path of 300 of the fabled tribe during his conquest of Persia, partaking in a 13-day tryst with the Amazon queen, Thalestris, in Hyrcania south of the Caspian Sea, satisfying her desire to beget a "kingly" child (Plutarch, 46.1–3). The governor of Media also sent 100 women from the region dressed as fabled Amazons to the Macedonian king. Clearly Alexander's desire to emulate his heroic 'ancestors' such as Heracles and Achilles resonated with those seeking his approbation.

We have more sober fragments from other Roman-era historians who recorded the presence of embassies from various Scythian tribes as Alexander journeyed through the provinces of the Persian Empire and the diplomacy between them. But we have scant record of the treasures Alexander sent back as campaign trophies, so undocumented precious goods may well have been sent to his mother, sister and half-sisters, including Scythian gifts or booty.

What is clear, however, is that Alexander took no Scythian wife, nor did he return a Scythian mistress to Macedon. Ultimately, Scythian tribes were hostile to the Macedonian advance and allegedly told Alexander that their unpretentious existence was epitomized by “a yoke of oxen, a plough, an arrow, a spear and a cup” (Curtius 7.8.17). After giving him a dressing-down for trying to “subjugate the whole human race” and “coveting things beyond his reach,” they joined forces with the local rebels to oppose the Macedonians until their chieftains were all but wiped out (Curtius 7.9.9 and 7.8.12). Another explanation was needed to explain the presence of the Vergina Scythian bow-and-arrow quiver.

It had already been pointed out that one of Philip's wives was a daughter of King Cothelas of the Getae tribe of the region of Thrace just south of the Danube. Both the Getae and Scythian women, it was argued, had a custom of ritual suicide to honour the death of their king. Herodotus (5.5) reported that in the case of Thracians, a favourite wife would have her throat slit after being praised by funeral onlookers, while those not chosen to die lived in great shame thereafter. Thracian and Scythian lands bordered one another at the Danube, where their customs, language, and even a mutual love of tattooing themselves appears to have emerged. The ritual death of a Thracian spouse, therefore, could explain the double burial in Tomb II.

This newly re-presented theory also rested upon questionable foundations. Philip's Getae wife was obscure with no martial associations, so she was unlikely to have been honoured by such a grandiose 'weaponised' burial. Additionally, at age 30-34, the Tomb II female was probably too old to have been one of Philip's later conquests, judging by the tender ages of his earlier brides. Nowhere in texts is the existence of Getae female cavalry units mentioned nor women horseback archers in Thrace, so Meda was not an obvious fit for the golden Scythian quiver.

A New Candidate

The worlds of Scythia and Macedon had clearly forged diplomatic relations with varying degrees of success and for commentators to have proposed the Tomb II female was Scythian on the basis of the quiver was a logical deductive leap. But it is the only Scythian artefact in her chamber; the other weapons and armour are not. What may have been overlooked is that in Philip's day there was a well-developed metalworking industry in Macedon itself which would have attracted the finest craftsmen. It is quite possible that a locally based artisan in the Macedonian capital at Pella was fabricating Scythian-styled goods for export to wealthy Scythian chieftains in these days of expanded diplomacy that stretched north of the Danube.

As an example, a gold scabbard now resides in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. It has a description which reads: “Although the scabbard is of Scythian type, the decoration is Greek in style and undoubtedly of Greek workmanship. Similar sheet-metal goldwork from the royal cemetery at Vergina in northern Greece and from kurgans... of Scythian rulers in the North Pontic region have been linked to the same workshop.” The same workshop is a statement born of another rare gold quiver unearthed in Russia with exactly the same pattern beaten into the precious metal as the Vergina example.

Since 1997 CE, when it first opened, the Archaeological Museum of Vergina has rather confidently placed nametags beside the tombs which draw in thousands of visitors each year. Tomb II, it boldly claims, housed Philip II and his Getae wife Meda. But in light of recent forensics on the bones and with some revisionary thinking on the metallurgy, we may see a new 'battle of the bones'. Because a never-before proffered identity has now been thrown into the debate ring: Cynane, daughter of Philip II, who was an attested warrioress who slayed an Illyrian queen in single combat. Ancient sources confirm she was buried at Aegae with honours some years after her father was entombed. The “Scythian-Amazon” may have learned the arts of war rather closer to home.

Archaeology in Greece can now plough new fertile territory with advances in DNA, radiocarbon dating, and stable isotope testing, and if the Ministry of Culture will finally permit these forensics on the bones from the royal tombs, we may finally have a definitive name for the mystery 'Amazon' of Macedon.