The diet of the Mongols was greatly influenced by their nomadic way of life with dairy products and meat from their herds of sheep, goats, oxen, camels, and yaks dominating. Fruit, vegetables, herbs, and wild game were added thanks to foraging and hunting. Once they established their empire, the Mongols came into contact with many new foodstuffs and recipes from across Asia, and these were often integrated into their own diet to create dishes such as roast wolf soup with pepper and saffron. Drinking huge quantities of alcoholic beverages was a major pastime of the elite with the most popular tipple of everyone from the Great Khans to lowly shepherds being fermented mare's milk, which is still drunk today across the Eurasian steppe.

Food

As nomadic herders of (in order of importance) sheep, goats, horses, Bactrian camels, and, at higher elevations, yaks, the Mongol people were much keener to keep their animals alive rather than eat them. A steady supply of milk (to make butter, cheese, yoghurt, and drinks), wool (to make felt and fleeces for clothing and tents) and dung (to be burned as fuel) could then be gained. Oxen, although not herded in great numbers, were also useful as a means to pull carts. However, special occasions and feasts (see below) did warrant meat dishes to be served; horse meat was preferred, but usually, it was the cheaper option of mutton or lamb. Meat was typically boiled and more rarely roasted because this process takes longer and so needed more precious fuel. Dried meat (si'usun) was an especially useful staple for travellers and roaming Mongol warriors. In the harsh steppe environment, nothing was wasted and even the marrow of animal bones was eaten with the leftovers then boiled in a broth to which curd or millet was added.

A welcome addition to the everyday diet would have been any herd animal which had died of natural causes or was too old to keep up with the herd. Being frugal, the Mongols often killed an animal by cutting open its chest and squeezing the heart or cutting an artery. In this way, no blood was lost and could be used to make sausages. Another dietary supplement was any animals caught as a result of hunting such as deer, antelopes, wild boars, marmots, wolves, foxes, and many wild birds (using snares and falconry). Freshwater fish were also sometimes eaten when possible but seem not to have appealed to most nomads.

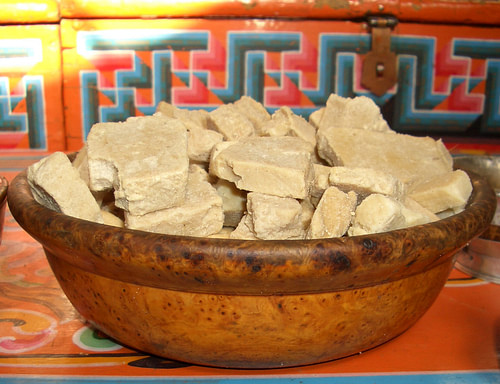

Dairy products were a major part of the Mongol diet. Butter was made and stored in leather pouches but was, instead of salting, given a longer shelf-life by the boiling process of its manufacture. A common food was fresh yoghurt, cream was added to dishes and another staple was qurut or dried milk curds. Cheese was often dried and cured by placing it on top of a yurt (ger) tent and exposing it to the wind and sun. Qurut was typically fermented or boiled in milk and was another handy food for travellers and warriors.

Nomads are also gatherers, and the Mongols collected useful dietary supplements such as wild vegetables, roots, tubers, mushrooms, grains, berries, and other fruit they came across in nature or via trade. As the empire spread so the Mongol people added bread, noodles, and grain-based foods to their diet, as well as exotic spices. Many herbs were collected and used as medicine for diseases, illnesses and injuries. Eating certain parts of wild animals considered to have potent spirits such as wolves and even marmots was thought to help with certain ailments, too. Donkey meat was considered a good remedy for wind and depression while bear paws helped increase one's resistance to cold temperatures. Such concoctions as powdered tiger bone dissolved in liquor, which is attributed all sorts of benefits for the body, is still a popular medicinal drink today in parts of East Asia.

Although nomadic men and women often interchanged chores, there was some division of tasks with women collecting food, cooking and processing it while men hunted, milked mares and produced the alcoholic beverages that were so popular.

Drink

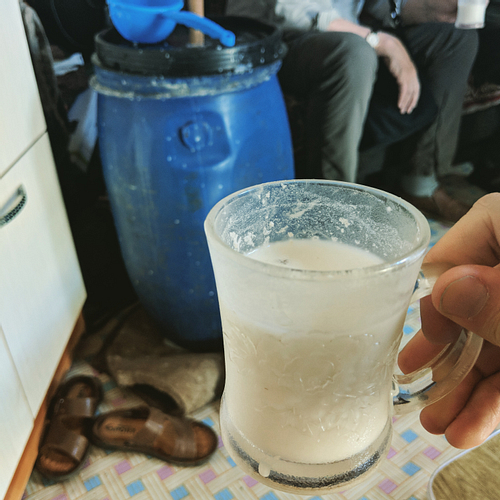

Drinking, especially large quantities of alcohol, was a very important part of Mongol culture and any important festival or gathering included rituals where all guests, both men and women, were expected to drink along to a beat of a drum or handclaps. Kumis was one of the most popular Mongol drinks and was typically made from fermented mare's milk (although the milk of sheep, oxen, camel, and yaks could be used, too). The drink was made by churning the milk in large leather bags using a wooden paddle, a process that took several hours. Known to the Mongols as airagh, it was an alcoholic summer drink and, because a season's supply required up to 60 horses, being able to drink it regularly was also a status symbol. The slightly fizzy drink was only 1-3% alcoholic, but this could be increased by various levels of distillation, the most laborious of which removed all solids and left a clear drink known as qara kumis or 'black kumis.'

Naturally, the Great Khan had his own unique and plentiful supply of airagh, provided by herds kept in the hunting park at the capital Xanadu for his exclusive pleasure. A small quantity of airagh was often flicked into the air to appease any evil spirits or consecrate a herd and, similarly, a small offering of the drink and a small piece of meat was often dedicated to deceased relatives. Still drunk today, it is often described as having a sour taste with an aftertaste of almonds.

Curiously, the Mongols rarely drank fresh milk as they were lactase deficient. Horse blood was drunk when water was in short supply, draining it from the animal's neck without killing it. Tea - in the form of concentrated black tea bricks boiled in milk - was only widely adopted by the Mongols from the 14th century CE onwards.

Other alcoholic drinks included honey wine, known as boal, and as the empire expanded so the Mongols were exposed to more and stronger alternatives than their mare's milk brew. Millet beer (buza), wine from grapes or rice, and many types of distilled liquors were drunk. The latter type, generally called arqi by the Mongols, were typically made from many varieties of fruit and grains and could be wickedly strong, up to 60 proof in some cases. Drinking to excess by both men and women seems to have been a social norm without any stigma attached to it (even having a certain honour), although cases of obesity and gout were common and many early deaths of Mongol leaders are attributed to alcoholism. The official record of the cause of death of Ogedei Khan (r. 1229-1241 CE), for example, was 'excessive drinking.'

Mongol Feasts

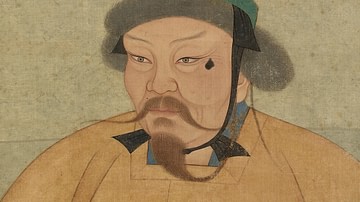

Feasts were held on the rare occasions that Mongol nomads got together in one place such as a meeting of tribal chiefs to elect a new leader or to celebrate important birthdays, weddings and so on. At these events, attended by both men and women, there was often a prescribed order of seating, eating and drinking, all depending on the seniority of the participants. Not receiving one's bowl before a less senior member of the clan could lead to fights. Special celebrations necessitated not only dusting off the best porcelain but also for more unusual food to be served and the historian George Lane gives the following summary of what a special Mongol meal at the imperial court might have entailed in the 13th century CE when the empire had expanded to bring in much more varied foods and ingredients than were previously available:

Appetizers might have included momo shapale with sipen mardur sauce, delicate steamed Tibetan mushroom ravioli smothered in a creamy, spicy yoghurt sauce. A salad of Bhutanese chilli and cheese might have followed. The main course, shabril with dresil, comprised Tibetan meatball curry with nutted saffron rice, honey, and currants. Himalayan steamed bread with turmeric and barley beer with honey would have accompanied the main food, and also as a dessert, Chinese chestnut mound with cream and glazed fruit would have found favour. (176-7)

Fortunately for posterity, many of these traditional dishes and how to cook them were recorded in the Yinshan Zhengyao, a sort of entertaining manual for the Mongol imperial court. Written by Hu Sihui in 1330 CE, the title may be translated as 'Proper and Essential Things for the Emperor's Food and Drink.' Below are a few choice feast dishes from that book, including a remedy for the morning after.

Roast Wolf Soup

Ingredients: wolf leg, cut up; three large cardamons; 15 g of black pepper; 3 g of kansi [asafoetida]; 6 g of long pepper; 6 g of 'grain of paradise' [or small cardamons]; 6 g of turmeric; 3 g of saffron.

Make a soup of ingredients. When done, flavour with onions, sauce, salt, and vinegar.

Jasa'a ['Mountain Oysters']

Use two. Remove testicle from scrotum. Salt and combine with kansi (about 3 g) and onions (about 30 g). Fry quickly in vegetable oil. Baste with saffron dissolved in water. Add spices. When ready, sprinkle with ground coriander.

Detoxifying Dried Orange Peel Puree

Ingredients: 500 g of fragrant orange peel (remove the white); 500 g of prepared mandarin orange peel (remove the white); 30 g of sandalwood; 250 g of kudzu flowers; 250 g of mung bean flower; 60 g of ginseng (remove green shoots); 60 g of cardamon kernels; 180 g of roasted salt.

Powder ingredients. Take in boiling water on an empty stomach.

(Buell, 329-331)

Legacy

Mongol cuisine might not have yet set the tastebuds racing of the world's culinary experts but they did make one or two lasting influences in the food department. The Mongol mutton and vegetable dish known as sulen (or shulen) - which is a broth, soup or stew depending how many extras are added - spread in popularity across the Mongol Empire and is still today eaten in many parts of Asia. Conversely, the Mongols, ever-willing to adopt elements of the cultures they conquered, experimented with new dishes and new mixes of ingredients to create brand new dishes. An example of this, according to the historian P. D. Buell, is the dessert baklava, the honey, nuts and pastry dessert now found everywhere but especially popular in Turkey, Greece, the Middle East, and North Africa. Made using layers of wafer-thin pastry, Buell points out that the Mongolian term bakla means 'pile up in layers' and that one of the earliest known recipes for the dessert derives from a Chinese encyclopedia written at the time of the Mongol domination of that country.

Finally, on many a menu around the world one can find 'steak tartare' - uncooked minced beef or horse meat - and this has its origins in the Mongolian people, known (incorrectly) by many other nations in the Middle Ages as 'Tartars'. According to the chronicler Jean de Joinville (1224-1317 CE), Mongol riders used to place under their saddle a portion of raw meat and the movement of the animal and rider would eventually pound all the blood out of it and make a flattened steak.