Glazed blue ceramic tiles or azulejos are everywhere in Portugal. They decorate the winding streets of the capital, Lisbon. They cover the walls of train stations, restaurants, bars, public murals, and fountains, churches, and altar fronts. Azulejos can be seen on park benches and paved sidewalks or adorning the facades of buildings and houses in towns and municipalities all over the country.

Traditional tile art tells the stories of Portugal's proud seafaring history by depicting navigators and the famous ships called the caravel. More modern tile art might show animals such as tigers and elephants – compositions inspired by oriental designs of the 17th century CE – or the contemporary geometric expressions of Portuguese artist Maria Keil (1914-2012 CE) who produced the stunning tilework for Lisbon's metro stations in the 1950s CE.

The distinctive blue of azulejos might lead you to think that the word derives from azul (the Portuguese word for blue). But azulejos has its origin in the Arabic term for a small, smooth polished stone - aljulej or azulej - and this evolved to azulejo in Portuguese (pronounced ah-zoo-le-zhoo).

Tile art is not merely decorative; it forms a visual historical record of Portugal. So let us take a tour of the national tile museum and discover the history of Portuguese ceramic tiles.

Visiting the Museu Nacional do Azulejo

To really appreciate the beautiful tile art of Portugal, a visit to Lisbon's national tile museum (Museu Nacional do Azulejo) is well worth the time. The museum preserves Portugal's ceramic art from the 15th century CE, and visitors will learn how the decorative language of azulejos traces the country's cultural identity and the evolution of techniques that were used in crafting azulejos.

The museum is located in the Xabregas district of Lisbon and covers three floors of the Madre de Deus Convent, founded in 1509 CE by Dona Leonor de Viseu (1458-1525 CE), widow of King Joao II (r. 1481-1495 CE). The golden and gilded interior is due to the renovation that took place after the Great Lisbon earthquake of 1755 CE, which partly destroyed the convent.

Historical Snapshot

The use of glazed and decorative ceramic tiles did not originate in Portugal, but stretches back to ancient Assyria and Babylon and shows us that the ancient world was filled with colour. Decorated tiles and bricks have been found on the walls of ancient Assyrian palaces. The Great Gate of Ishtar, which stood at the entrance to Babylon, is perhaps the most famous example of ancient tile art. The Babylonian King Nebuchadnezzar II (r. 605/604-562 BCE) ordered the gate to be constructed c. 575 BCE, and it features lions, young bulls (aurochs), and dragons (sirrush) against a vibrant cobalt blue glazed background.

In ancient Egypt, Pharoah Djoser (c. 2670 BCE), who was the first king of the Third Dynasty of Egypt, had his funerary chamber in the Step Pyramid of Djoser at Saqqara covered with blue faience tiles with yellow lines for papyrus stems.

Lead glazing was known to the Romans who first used the technique in the 1st century BCE. The Greco-Roman world, however, favoured the mosaic technique which was created by setting tesserae — small pieces of stone or glass — into intricate designs on floors and walls in public buildings, private homes, and temples. They also decorated surfaces by painting on wet lime plaster (called the fresco technique) and applying interior or exterior plaster to create relief effects (called stuccowork).

In countries where Islamic culture flourished, wall tiles using geometric designs became an important aspect of tile art and religious expression. Islamic potters developed lustre tiles for use in palaces, mosques and holy shrines, which gave these buildings a distinctive iridescent finish.

Perhaps the earliest example of Islamic tile decoration can be seen on the Mosque of the Dome of the Rock (Qubbat al-Sakhra) located on the Temple Mount in Jerusalem. It was erected by the Muslim caliph Abd el-Malik in 688-691 CE, but Suleiman the Magnificent (1520-1566 CE) was responsible for the mosque's renovation and the replacement of exterior mosaics with shimmering tiles.

Sultan Ahmed Mosque in Istanbul, Turkey is known as the Blue Mosque because more than 20,000 striking blue and white Iznik tiles cover its interior. Iznik was a Turkish centre of tile and ceramic production for the Ottoman Empire in the late 15th century CE.

You may be wondering why the ancient world seemed to be saturated in blue, and that is because the semi-precious stone lapis lazuli (which means “stone of the sky”) was prized in antiquity for its royal blue hue and was thought to be connected with knowledge, insight, and magical powers.

Islamic & Italian Influences

The Moors brought Islamic mosaic and tile art to the Iberian Peninsula in the 8th century CE and it is here that our story really begins.

King Manuel I of Portugal (r. 1495-1521 CE) visited Seville and the Alhambra palace in Granada and was dazzled by the Islamic geometric-patterned ceramic tiles he saw. King Manuel was one of the wealthiest monarchs in the Christian world thanks to the Portuguese age of discovery (early 15th - mid 17th century CE). He imported azulejos from Seville and decorated The Arab Room in his palace at Sintra (Palácio Nacional de Sintra). The Spanish Muslim geometric patterns used in this room are called mudejar, and this period of tile decoration is known as the Hispano-Moresque.

The palace at Sintra remained largely intact after the 1755 CE earthquake destroyed most of the city. Should you visit the national tile museum, you should also take a tour of the palace at Sintra (around 25 km or 15 m north of Lisbon).

The highlight of the Museu Nacional Do Azulejo is the 1,300 traditional blue and white panoramic panel called The Great View of Lisbon. Located on the top floor, it is 23 metres (75 ft) in length and was made by the Spanish-born tile painter Gabriel del Barco (c. 1649-1701 CE) in 1700 CE. It is one of the few extant visual records of the cityscape before the devastating earthquake.

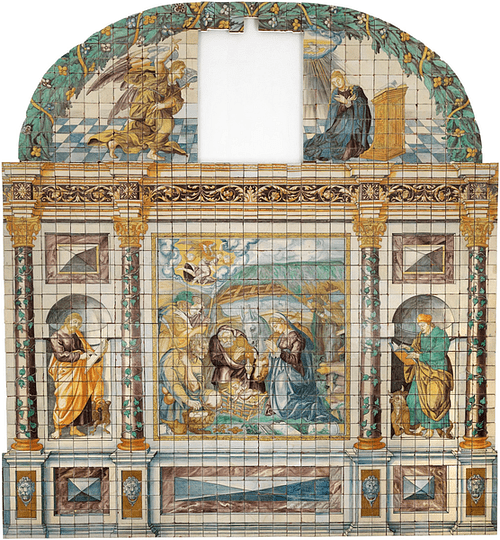

But perhaps the most fascinating example of Portuguese tile art is the polychrome panel known as Nossa Senhora da Vida (Our Lady of Life) located on the first floor of the museum. It is Portugal's oldest azulejo and is an important piece of 16th-century CE Portuguese tile production.

Following the Reconquista – when Spanish and Portuguese territories on the Iberian Peninsula were taken back from Muslim control – the Portuguese were free to develop their own style of hand-painted azulejos. Tile painters were no longer bound by Islamic law that forbade the portrayal of human figures and they could now paint animals and humans, historical and cultural events, religious imagery, flowers, fruit, and birds.

By the mid-16th century CE, Italian and Flemish artisans were settling in Lisbon, attracted by the flourishing tile art and the possibilities of working with new techniques. One of these techniques was the Italian majolica, which made it possible to paint directly on the tiles and depict a more complex range of designs such as figurative themes and historical stories. Nossa Senhora da Vida is a superb example of the influence of majolica and Renaissance influence (the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity that took place from the 14th to the 17th centuries CE).

The 1580 CE panel consists of 1,498 azulejos painted in trompe l'oeil (a style of painting that is intended to give a convincing illusion of reality). It is an early and outstanding example of Portuguese religious iconography and includes images of the adoration of the shepherds and John the Evangelist (c. 15 – c. 100 CE). The blue and white squares create illusory depth, while the green, yellow, and blue painted figures and patterns imitate a painted board with a gold gilt frame. The rectangle in the upper lunette indicates that a window was once in the azulejo (it was originally a retable wall in the Church of Santo André in Lisbon).

The Portuguese Style

The 1st Marquis of Pombal, Sebastião José de Carvalho e Melo, (1699-1782 CE), presided over the reconstruction of Lisbon and architectural ceramic tiles started to follow the so-called Pombalino style. Known as azulejos pombalinos, ceramic tiles moved from the interior of churches and buildings to the exterior – covering public and religious monuments, palaces, stairway walls, houses, restaurants, and gardens. Azulejos pombalinos were also considered an effective and low-cost building solution.

Up to this point, the church and nobility had commissioned decorative ceramics, but we start to see the democratisation of tiles because of their extensive use in urban housing and the rebuilding of the city. To meet demand, the Real Fábrica de Louça tile production factory opened in the Rato district of Lisbon, and 1715 CE saw the last foreign import of ceramic tiles.

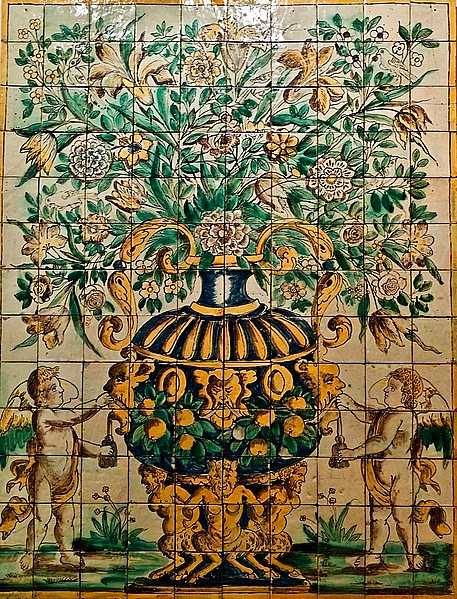

The Portuguese overseas expansion starting in the early 14th century CE resulted in a meeting of many cultures, and azulejos reflected a sense of the exotic by including elephants, monkeys, and indigenous peoples from colonies and territories such as Brazil. Indian printed textiles showing Hindu and nature symbols became fashionable between 1650-1680 CE, particularly a composition called aves e ramagens ("birds and branches").

The Leopard Hunt (1650-1675 CE), which is on display at the museum, incorporates themes from Portugal's overseas conquests along with European cultural traditions. The polychrome faience panel came to the museum from Quinta de Santo António da Cadriceira in Torres Vedras (about 50 km or 30 miles north of Lisbon) and shows a female leopard being hunted by indigenous people crowned with feathers.

The Chicken's Wedding panel (1660-1667 CE) demonstrates the creative flair of Portuguese artisans in the 17th century CE but it also shows how commissioned azulejos often spread social satire or political messages. In this large panel, a chicken is conveyed in a carriage that is escorted by a cortege of monkeys playing musical instruments. Singerie (French for “Monkey Trick”) is the name given to a visual image in which fashionably dressed monkeys display human behaviour, and it emerged as a distinct genre in the 16th century CE.

The panel is at the museum and a tour guide might tell you that monkeys are often linked to satire and that The Chicken's Wedding could be interpreted as a political commentary on Spain and its supporters during the War of Restoration (1640-1668 CE), which ended 60 years of dual monarchy in Portugal and Spain under the Spanish Habsburgs and established Portugal's new ruling dynasty: the House of Braganza.

By the early 18th century CE, Portuguese tile artisans had fallen under the influence of Ming Dynasty (1368-1644 CE) Chinese porcelain design and Dutch Delftware, both of which led to the cobalt blue and white visual appearance of the Portuguese tiles that are seen all over Portugal today.

The Baroque (c. 1600-1750 CE) and Rococo (c. 1700-1800 CE) movements resulted in a style of azulejos that is unique to Portugal – figuras de convite or invitation figures. These were ornate life-size figures, usually a finely dressed nobleman or woman, and they were fixed to the walls of stairways and at entrances to palaces to welcome or invite guests inside. They made direct eye contact with people and one can only imagine the surprise guests received when coming upon one of these figures. Invitation figures were a design innovation for the Portuguese because they were outlines or cut-outs rather than the traditional square tile composition.

After the flirtation with ornate flourishes and often macabre themes during the 17th and 18th centuries CE, azulejos designs of the 19th century CE catered to the tastes of the newly emerging bourgeoisie (a social order that was dominated by the so-called middle class). The bourgeoisie wanted azulejos to reflect their social success and status and the nouveau-riche emigrants returning from Brazil brought with them the trend of decorating the facades of their houses with ceramic tiles that kept the interior cool and reduced outside noise. As a result, there was a move away from large panels to smaller and more delicately executed azulejos.

Industrialisation introduced new techniques such as the transfer-print method on blue and white or polychrome azulejos, although hand-painted tiles remained popular. Mass production meant that tiles could be produced at a lower cost and a greater variety of stylized designs, from traditional patterns to foreign adaptations, could be offered.

The Art Nouveau period (c. 1890-1910 CE) saw facades decorated with the flowing, curved lines of flowers, plants, vines, leaves, insects, and animals that were typical of the Art Nouveau movement. The cultural elite, however, started to view tile art as old-fashioned and dismissed it as being for the masses.

By the early 20th century CE, ceramic tile art had fallen out of favour and was in danger of becoming a lost art, but thanks to contemporary Portuguese artists like Maria Kell, there was a revival in the 1950s CE as metro stations were constructed and tiles were used in murals as modernist works of art.

Public Art

You can spend hours at the museum, going room by room through Portugal's visual history, but you can also stroll down any street in Lisbon and see azulejos that have weathered rain and sun for hundreds of years. Often you will see someone outside their house cleaning and polishing azulejos.

When you reach the museum, sit down at the café, sip a galão - the Portuguese coffee that is like a milky latte - and you will see an amazing 18th-century CE azulejo panel showing pigs and fish hanging up and waiting to be prepared for cooking.

How To Get There

The Museu Nacional do Azulejo is located on Rua da Madre de Deus 4, Lisbon. You can take bus 794 from Comercio Square and this will drop you at the entrance to the museum. Or you can enjoy a 20-minute walk from Santa Apolonia metro station, stopping to look at street azulejos along the way. There is a handy map on the museum's website.

The museum is open Tuesday to Sunday from 10.00 am to 6.00 pm with the last admission being at 5.30 pm.

Before your visit, you can download a mobile app that offers a guided tour of the most significant azulejos on exhibition.

And if you want to start your own azulejos collection, you can take a workshop at the museum on creating faience tiles - what design would you do?