The clothing worn by the Mongols in the 13th and 14th century CE, like most other aspects of their culture, reflected their nomadic lifestyle in the often harsh climate of the Asian steppe. Typical items included felt hats, long jackets with loose sleeves, and practical baggy trousers. As the Mongol army was based on fast-moving, lightly armed cavalry, recruiters usually had a relaxed 'come-as-you-are' approach to uniforms so that clothes in both war and peace were often very similar. Heavy cavalry units did wear armour made from padded materials, hardened leather and pieces of metal. Many of the Mongol clothes of the medieval period are still worn by nomadic peoples today across Eurasia.

Climate & Significance

The typical weather of the Asian steppe is cold, dry, and windy. Winters can be long - from September to May - and bitterly cold (down to -34 degrees Celsius or -30 degrees Fahrenheit). Summers are short but can be hot, reaching a temperature over 30 degrees Celsius (86 degrees Fahrenheit). Clothing needed, then, to be warm and durable but also layered for the rare moments when temperatures soared. As Mongols were often on the move and rode horses, their clothing also had to be unrestrictive.

Another consequence of nomadic life was the absence of a large number of material possessions, thus, cloth and clothing were one of the important assets of a family and were given as gifts and as part of a bride's dowry. Male friends and blood brothers often exchanged a leather belt while rulers gave sumptuous clothing to fellow rulers as diplomatic gifts and to senior officials on special occasions such as royal births and weddings, or to reward loyal service. Even the absence of clothing had a significance such as when belts and hats were removed before making prayers (including by the khans), belts of onlookers had to be removed and slung over the shoulder during succession ceremonies to demonstrate obedience, and sometimes the accused in a law court was stripped before sentence.

Materials

Sheep provided fleeces and wool to make felt, which does not need to be weaved but is made by pounding the wool and causing its microscopic barbs to form interlocking sheets. Felt was used for clothing, blankets, and the yurt tents which are still used today by Asian nomads. Goats were herded in large numbers and the principal source of leather.

Through hunting, trade, or tribute from conquered peoples, the Mongols acquired furs such as sable, squirrel, rabbit, fox, monkey, dog, goat, and wolf. Exotic or difficult to obtain furs like snow leopard and lynx were especially prized and reserved for the elite members of society. In the coldest periods, fur garments were worn in a double layer with the inner layer having the hair on the inside and the outer layer the opposite way around. Such materials as silk could be acquired through trade and became much more easily available once the Mongols had conquered China; undergarments were worn by both men and women made from this material.

Making felt, leather, and clothes, and then repairing them were all the tasks expected of Mongol women. Washing was one chore that did not happen very often due to the lack of water in the usually arid steppe environment. Foreign travellers of the period frequently comment on the dirtiness of the Mongols and their clothing and such habits as wiping their hands on their trousers after eating. In any case, regular washing was not desirable for nomadic outer clothing because it was often greased with animal fat to make it wind and waterproof.

Outer Clothing

The most recognisable piece of outer clothing for Mongol men and women, still widely worn today, was the short robe or deel. This one-piece long jacket was folded over and closed on the left side of the chest (left breast doubled over the right) with a button or tie positioned just below the right armpit. Some deel had pockets and the sleeves typically went only down to the elbow. The outer lining of the robe was of cotton or silk and heavier versions had an additional fur or felt lining or a quilt padding. The inner lining was typically turned over a little to the outside of the garment at the sleeves and hem. For those who could afford it, the robe might have some exotic fur trim at the collar and edges.

A wide leather belt was worn which had useful hanging pouches and which might be decorated with ornate metal pieces (metal of any kind being a rarity for nomadic peoples). The belts of women were even more decorative than those of the men. In winter a heavy coat of fur or felt was worn over the deel robe. Under the robe another thin robe might be worn or a simple cotton or silk undershirt. Trousers were worn under the ever-present robe. Winter trousers could be made entirely from fur or have cotton, wool or silk padding, the latter being an excellent light insulator.

Hats & Boots

Boots were made from felt or leather with the sole usually being a thickened layer of felt and the boots high enough to tuck in the trousers. Boots had no heels and were fastened tight using laces. The feet were kept warm with thick felt stockings. The classic Mongol hat was conical and made from felt and fur with flaps for the ears and an upturned brim at the front. Sometimes the brim was divided in two. In summer a light head-cloth might be worn to keep off the sun.

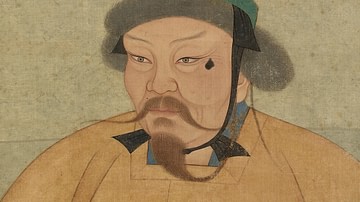

Elite men and women distinguished themselves by sporting a few peacock feathers in their hats. One of the few areas where women distinguished themselves from men, and then only elite women, was the elaborate boqta headdress which had pearls and feathers decoration. One can still see these headdresses today when, for example, Kazakh women attend traditional festivities. While both men and women wore earrings, women also added metal, pearl, and feather decorations to their hair. Men, on the other hand, did not have much opportunity to do the same as they seem to have shaved the crown of their head, sometimes leaving only a thin strip of hair at the front of the head and with locks dangling down to the eyebrows. The hair left on the back of the head was commonly grown long and tied into two braids. Mongol men often have a wispy goatee beard and drooping moustache in medieval illustrations.

The Imperial Court

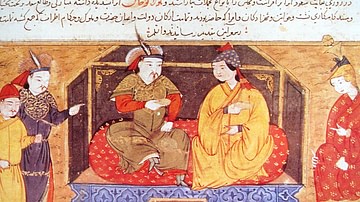

When the Mongols conquered Song Dynasty China (960-1279 CE) some of the rulers and elite adopted Chinese-style clothing such as richly-embroidered silk robes. Marco Polo (1254-1324 CE), the Venetian traveller who served Kublai Khan (r. 1260-1294 CE) and wrote of his experiences in his Travels (circulated from c. 1298 CE), gives the following description of the sumptuous clothes worn at the Mongol Yuan Dynasty court during important religious festivals:

…the grand khan appears in a superb dress of cloth of gold, and on the same occasion full twenty thousand nobles and military officers are clad by him in dresses similar to his own in point of colour and form; but the materials are not equally rich. They are, however, of silk, and the colour of gold; and along with the vest they likewise receive a girdle of chamois leather, curiously worked with gold and silver thread, and also a pair of boots. Some of the dresses are ornamented with precious stones and pearls to the value of a thousand bezants of gold.

(Book II, Ch. XI)

The account clearly shows that traditional Mongol dress had not changed all that much, only the materials with which it was made. At the other end of the wardrobe scale, Marco Polo also mentions that monks he came across in Mongolia wore hemp clothing of a black a dark colour.

Armoured Warriors

While warriors wore pretty much their peacetime clothes some sensibly added armour to better protect themselves. Mongol armour was usually light so as to not impede the speed of cavalry riders or the use of a bow. A quilted robe or leather jacket offered some protection against arrows and the traditional robe could be reinforced with strips of hardened leather, bone or metal. Learning from the Chinese, a silk undershirt might be worn as this had the handy consequence of wrapping around the arrowhead if one was struck, protecting the wound and making the arrow easier to withdraw.

Plate armour and chain mail were rare but using small plates of metal or pieces of hardened leather which were then stitched together to make a suit were more common. Leather pieces were often given a layer of crude black lacquer to make them waterproof. Stitching was done using leather ties and one medieval chronicler noted that Mongol metal armour was so highly polished you could use the pieces as a mirror. Armoured coats, like the deel, hung down to the knees and covered only the upper arms. Some contemporary descriptions mention a silk surcoat worn over the armour which could be intricately embroidered. Warriors typically wore heavy leather boots. At the other end of the body, the head was protected by either an iron or hardened leather helmet, sometimes with a neck guard and a central top spike or ball and plume.