The peoples of the Mongol Empire (1206-1368 CE) were nomadic, and they relied on hunting wild game as a valuable source of protein. The Asian steppe is a desolate, windy, and often bitterly cold environment, but for those Mongols with sufficient skills at riding and simultaneously using a bow, there were wild animals to be caught to supplement their largely dairy-based diet. Over time, hunting and falconry became important cultural activities and great hunts were organised whenever there were major clan gatherings and important celebrations. These hunts involved all of the tribe mobilising across vast areas of steppe to corner game into a specific area, a technique known as the nerge. The skills and strategies used during the nerge were often repeated with great success by Mongol cavalry on the battlefield across Asia and in Eastern Europe.

Hunted Animals

The Mongols, like other nomadic peoples of the Asian steppe, relied on milk from their livestock for food and drink, making cheese, yoghurt, dried curds and fermented drinks. The animals they herded - sheep, goats, oxen, camels and yaks - were generally too precious as a regular source of wool and milk to kill for meat and so protein was acquired through hunting, essentially any wild animal that moved. Animals hunted in the medieval period included hares, deer, antelopes, wild boars, wild oxen, marmots, wolves, foxes, rabbits, wild asses, Siberian tigers, lions, and many wild birds, including swans and cranes (using snares and falconry). Meat was especially in demand when great feasts were held to celebrate tribal occasions and political events such as the election of a new khan or Mongol ruler.

A basic division of labour was that women did the cooking and men did the hunting. Meat was typically boiled and more rarely roasted and then added to soups and stews. Dried meat (si'usun) was an especially useful staple for travellers and roaming Mongol warriors. In the harsh steppe environment, nothing was wasted and even the marrow of animal bones was eaten with the leftovers then boiled in a broth to which curd or millet was added. Animal sinews were used in tools and fat was used to waterproof items like tents and saddles.

The Mongols considered eating certain parts of those wild animals which were thought to have potent spirits such as wolves and even marmots a help with certain ailments. Bear paws, for example, were thought to help increase one's resistance to cold temperatures. Such concoctions as powdered tiger bone dissolved in liquor, which is attributed all sorts of benefits for the body, is still a popular medicinal drink today in parts of East Asia.

Besides food and medicine, game animals were also a source of material for clothing. A bit of wolf or snow leopard fur trim to an ordinary robe indicated the wearer was a member of the tribal elite. Fur-lined jackets, trousers, and boots were a welcome insulator against the bitter steppe winters, too.

Horses & Bows

Mongols were proficient hunters not only because they had to be in order to eat but because they trained from a very young age to ride and fire a bow. A second aid was the Mongol horse, a small but sturdy beast with excellent stamina. Thirdly, hunters had a great weapon, the Mongol composite bow. Made of multiple layers of wood, bamboo or horn, the bow was strong, flexible and, because it was strung against its natural curve, it could shoot arrows with a high degree of accuracy and penetration. Arrowheads tended to be made from bone and, much more rarely, metal while shafts were made from wood, reed, or a combination of both, and fletchings from bird feathers. Hunters could shoot with accuracy while riding their horses at speed thanks to stirrups and wooden saddles with a high back and front which gave better stability.

The Nerge

To make a hunt a success, the Mongols participated in great numbers in a coordinated annual attack on a designated area of steppe. This strategy was called the nerge (aka jerge or jarga) and was traditionally held early each winter over at least a month-long period, principally in order to fill up the larder to last through the leanest time of the year. During the empire, organised hunts around the capital were expected to deliver game for consumption at the imperial court.

During the nerge a long line of riders covering a line up to 130 kilometres (80 miles) and marked out by flags moved from the outer end inwards to eventually enclose a large pre-selected geographical area. The riders, accompanied by hunting dogs, then gradually moved, over a period of several weeks, in towards a smaller pre-designated circular zone, also marked out with flags beforehand, so that the animals driven there could more easily be killed. The riders worked in shifts to ensure no animals escaped the cordon, and anyone who did let an animal through the line was severely punished. Once the animals were penned in, only the khan could open the hunting with the first shot and anyone starting off before him was executed. After the hunt, some animals were deliberately allowed to escape the entrapment in order to ensure the conservation of the game for future hunts. A nine-day feast traditionally marked the climax and close of the nerge.

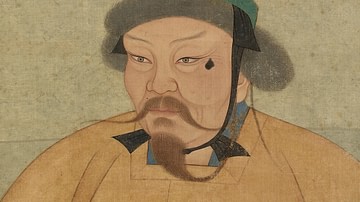

The Venetian explorer Marco Polo (1254-1324 CE) travelled to Xanadu during the reign of Kublai Khan (1260-1294 CE) and he gives more details of a nerge in his book The Travels, first circulated c. 1298 CE. When the khan goes on the annual hunt, Polo tells us, the whole operation is supervised by two officials, the 'masters of the chase', called chivichi who are brothers and who control the hounds and mastiffs. Each official has 10,000 men under his command, and these wear either a blue or red uniform depending on which chivichi they must obey. Polo goes on to say,

The dogs of different descriptions which accompany them to the field are not fewer than five thousand. The one brother, with his division, takes the ground to the right hand of the emperor, and the other to the left, with his division, and each advances in regular order, until they have enclosed a tract of country to the extent of a day's march. By this means no beast can escape them. It is a beautiful sight to watch the exertions of the huntsmen and the sagacity of the dogs, when the emperor is within the circle, engaged in the sport, and they are seen pursuing the stags, bears, and other animals, in every direction.

(Bk. 2, Ch. 15)

The exact same strategy of the nerge was used by fast-moving light cavalry in Mongol warfare. Sometimes the wings of cavalry were so extended that an opposing army was eventually entirely surrounded. A reserve of heavy cavalry then moved in for the kill and, as with the animal hunts, some of the enemy were allowed to escape, but this time only to ensure the Mongols were not themselves numerically overwhelmed. Any escapees, unlike with the game, were then ruthlessly pursued, often for days after a battle.

As the noted historian E. Gibbon summarised in his seminal work The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, the nerge and warfare became, or indeed, always were, one and the same thing:

The leaders study, in this practical school, the most important lesson of the military art: the prompt and accurate judgement of ground, of distance, and of time. To employ against a human enemy the same patience and valour, the same skill and discipline, is the only alteration which is required in real war; and the amusements of the chase serve as a prelude to the conquest of an empire. (quoted in Morgan, 75)

The technique of the nerge was used to great effect to cut off armies of the Rus princes from fortified cities when the Mongols invaded that area in 1237-8 CE. The nerge was even successfully used with a naval element against a combined land army and naval force of China's Song Dynasty at the battle of Yaishan in 1279 CE.

The Hunting Park of Xanadu

Hunting was such a part of Mongol culture that even when they established their empire and began to settle down to a more sedentary existence, the old traditions were not forgotten. Rulers even ensured they had their own private hunting parks when they swapped their traditional yurt tents for ornate palaces. To the immediate northwest of the Mongol capital Xanadu there was a hunting preserve which consisted of meadows, woods, and lakes, and which was populated by semi-tamed animals such as deer. The hunting preserve was also used for falconry and keeping herds of white mares and special cows whose milk was reserved for the khans and those given that privilege. To keep the animals in and the uninvited out, the whole preserve was enclosed in an earth wall and moat.

Marco Polo describes the hunting preserve, thus:

Within the bounds of the royal park there are rich and beautiful meadows, watered by many rivulets, where a variety of animals of the deer and goat kind are pastured, to serve as food for the hawks, and other birds employed in the chase…

(Bk. 1, Ch. 57)

The khan's hunting birds are also described, "His majesty has eagles also, which are trained to stoop at wolves, and such is their size and strength that none, however large, can escape from their talons" (Bk. 2, Ch. 14). Other birds of prey used include gerfalcons, peregrine falcons, sakers, and vultures. The khan and other nobles ensured none of their precious birds was lost by attaching silver tags to their legs with the name of the owner and keeper. If the finder of a lost bird did not recognise the names on the tag then he had to take it to a special 'lost property' officer, the bulangazi, who kept it and awaited the rightful owner in his tent in a prominent part of the camp, which was indicated as the lost property office by a special flag. Falconry and the use of eagles to hunt game is still very much a part of life on the Asian steppe today.