Throughout history, in order for a government to be respected and obeyed, it must possess some form of legitimacy recognized by the governed. Governmental systems have relied on a number of models for legitimacy, among them the dynastic form in which the son or close relative of the monarch succeeds to the throne and passes power down to the next generation. The dynastic model frequently includes the component of the 'divine right' of a ruler whereby the monarch is thought to have been chosen by the gods, or a single god, to rule according to divine will. In ancient China, legitimacy of rule was this very combination, but the will of the gods was paramount. A dynasty was considered just and worthy to rule only as long as it upheld divine will, and that will was clearly expressed in how well the government cared for the people.

The divine will in China came to be manifest in what was known as the Mandate of Heaven – the gods' contract with a monarch giving him the right to rule. When the ruling house showed clear signs that the people were no longer its primary interest, the government was thought to have lost that mandate and another dynasty would replace it.

Although this policy of legitimization worked well enough philosophically, problems arose when more than one dynastic house – or state – lay claim to the mandate at the same time. How could it be proved, after all, that one faction was truly working in the best interests of the populace when another could provide evidence that it was doing this same thing? In 184 CE, during the waning of the Han Dynasty (206 BCE - 220 CE), this set of circumstances erupted in the social chaos of the Yellow Turban Rebellion, resulting in thousands of dead, vast swaths of land destroyed, and the disintegration of order into chaos, until the rise of the Three Kingdoms and, even then, conflict continued.

The struggle to legitimize claim to the Mandate of Heaven, in fact, would fracture the country until its reunification in 280 CE under the Jin Dynasty (splintered early on by the War of the Eight Princes over succession) with stability only achieved by the Liu Song Dynasty in 420 CE.

The Mandate of Heaven

The concept of the Mandate of Heaven dates back to the Zhou Dynasty (1046-256 BCE) and its first king, Wu (r. 1046-1043 BCE). Prior to the Zhou, China was ruled by the Shang Dynasty (1600-1046 BCE) and Wu's older brother, according to legend, had been killed by the king of the Shang. Wu and his family claimed the death was unwarranted and wanted justice, but the Shang were the ruling house and it was thought they held power by the will of the god Shangti – supreme god of creation, law, order, and justice – and so could not be touched.

In order to justify a move against the Shang, Wu and his father Wen (and the rest of the family) had to find a new basis for legitimization, one which could be used to show that the Shang were unjust tyrants undeserving of the monarchy, and so the Mandate of Heaven was created. Shangti was the most popular god of the era and would be difficult to displace and so the Zhou claimed a previously unknown aspect of Shangti's relationship with the Shang: the god had forged a contract with the rulers of China which was only good as long as the monarchy kept its side of the bargain. Since the Shang had broken its faith with Shangti through tyranny and unjust practices, Shangti had withdrawn the Mandate of Heaven from them and given it to the Zhou.

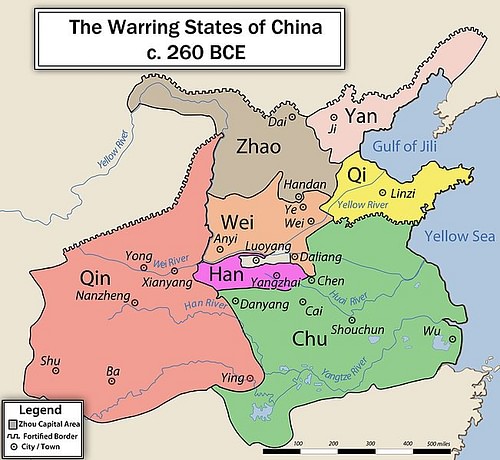

The Zhou overthrew the Shang and established their new order but, owing to the vastness of their region, decentralized during the so-called Spring and Autumn Period (772-476 BCE) and began a slow decline. As their authority dwindled, it was said that they had lost the Mandate of Heaven and seven separate states claimed the mandate, each for itself, during the Warring States Period (476-221 BCE). Each one of these tried to show that the Zhou had forfeited the mandate, which was now rightfully theirs, by proving their worth in battle but none could best any of the others.

The state of Qin finally conquered the rest and unified China through a policy of total war, without regard for the traditional rules of chivalry and honor, and Shi Huangdi (r. 221-210 BCE) became the first emperor of China. The Qin Empire was famously brutal and repressive and so, even though there were many who felt they never had the mandate to begin with, there was nothing to be done to dislodge them until Shi Huangdi died in 210 BCE. The country again erupted in civil wars culminating the Chu-Han Contention between the states of Chu and Han; the Han won and the Han Dynasty was born.

Han Dynasty Decline

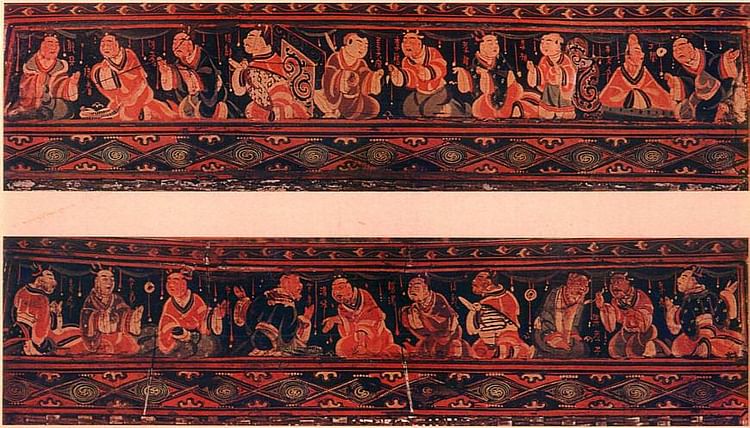

The Han is one of the best-known dynasties of ancient China owing to its technological developments, the opening of the Silk Road, its art, and the general encouragement of cultural and spiritual refinement. Toward the end, however, the government had become corrupt to the point where people were able to buy their positions instead of earning them on merit.

Compounding the government's problems was that the actual power no longer lay with the Chinese emperor but with the palace eunuchs. Eunuchs had existed earlier as guards of the palace harem but, during the Han Dynasty, their influence extended into politics. Scholar Justin Wintle explains:

Concubinage and eunuchry were commonplace throughout the ancient world. Every hereditary ruler wanted a son to succeed him, and what better way to ensure a direct male succession than a plurality of “wives”? Yet the larger the harem, the greater the risk that conception might occur away from the royal bedchamber. Only by employing eunuchs to guard and administer his concubines, could a ruler presume their “purity” remained intact. (104)

The power of the eunuchs grew from harem guards to royal advisors as Han Dynasty rulers came to rely on them more and more as a kind of buffer between the various political factions of the palace and themselves. A trusted eunuch could be employed as a spy or equally well as an assassin but, on a daily basis, could deflect or delay policy requests or other entreaties and give the emperor some space. By the time of the reign of the emperor Lingdi (168-189 CE), the eunuchs had become the actual power behind the throne, epitomized in the Ten Eunuchs (also known as the Ten Attendants), the trusted advisors and councilors to the emperor.

Yellow Turban Rebellion

While the eunuchs and the court were engaged in their various political games, the people of China were suffering. As early as 142 CE, the people's disgust with their government found expression in the Five Pecks of Rice Rebellion (also known as the Way of the Five Pecks of Rice, so called because anyone wishing to join had to donate five pecks of rice) led by the Taoist visionary Zhang Daoling. Zhang formed a theocratic state in the Hanzhong Valley in defiance of the government, claiming the emperor had lost the Mandate of Heaven and Zhang and his followers were, in effect, seceding from China.

No one in the government did anything about Zhang or his claims (the situation was not dealt with until the general Cao Cao subdued the separate state c. 215 CE) and this encouraged another Taoist visionary, Zhang Jue (also known as Zhang Jiao, d. 184 CE, no relation to Zhang Daoling), to press the claim further in the full-scale revolt known as the Yellow Turban Rebellion (also the Yellow Scarves Rebellion, because of the color of their headwear). Zhang and his two brothers (Zhang Bao and Zhang Liang) were Taoist healers who treated their patients for free because the peasantry had so few resources. They saw, on a daily basis, how the people were suffering while the government did nothing to help them and so Zhang, a charismatic leader, launched a local revolt which quickly became nationwide rebellion.

The basic claim of the Yellow Turbans was that the Han had clearly lost the Mandate of Heaven as evidenced by the corruption of the court and the suffering of the people. The Han government no longer worked for anyone but itself, they claimed, and so they could legally be deposed. They pointed out the fact that, when the Han first came to power, they associated themselves with Tian (heaven) and the color blue but then, as they engaged further with the people, aligned themselves with the earth and the color yellow but, by 184 CE, were associating themselves with fire and the color red. Why the Han did this is unclear but, to the Yellow Turbans, it was a certain sign of their betrayal of the people and loss of the mandate.

The rebels invoked the spiritual principle of jiazhi (literally “worth” or “value”) which was the essential, fundamental significance of any given individual or action. The jiazhi of a person was their worth as a person, without any other consideration of what they contributed to a community. Every life had an essential, divine value, and every action that proceeded from that individual life shared in that value. Each individual, therefore, was precious and unique and should be treated with respect and dignity. The Han emperors, who favored Taoist beliefs, mouthed this same outlook but did not act on it, preferring instead to occupy their time with court intrigues and lucrative international trade. The Yellow Turban Rebellion brought the government's attention back to the people they were supposed be caring for.

Suppression & Conflict

The rebellion quickly gained momentum as Zhang Jue's vision of recognizing the peasantry's essential jiazhi spread. Zhang and his brothers found enthusiastic participants in their patients who then spread the word to others, introducing the movement through a poem-slogan:

The Blue Sky is gone; the Yellow Sky will rise

In this year of jiazhi, there will be prosperity under Heaven.

The phrase “under Heaven” was understood to refer to China and the blue and yellow sky, of course, to the Han and Yellow Turbans respectively. All people would be equal, Zhang preached, and this would result in a Great Peace in the land where wealth was shared and no one was forced to go without food or shelter. At the same time he was proclaiming his Great Peace, however, he was mobilizing the people for armed conflict to demand that peace through military action, knowing the government would not grant it willingly, and he was right.

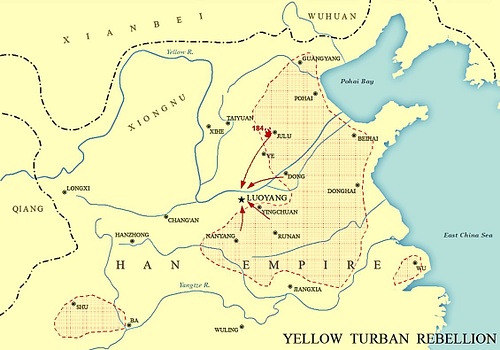

The Han moved quickly to suppress the rebellion but their resources by this time were spread far and thin. Invasions by the nomadic Xianbei and Xiongnu tribes had necessitated garrisoning border fortresses commanded by regional governors/commanders who were quickly mobilized. While the Han drew up its armies, the rebel forces were increasing daily and spreading. Yellow Turban enclaves were appearing all over China and their ranks were swelling into the thousands and then tens of thousands.

The first Han generals sent against the rebels were Huangfu Song (d. 195 CE), Lu Zhi (d. 192 CE) and Zhu Jun (d. 195 CE) but the rebellion was finally ruthlessly crushed by the poet-warrior Cao Cao (l. 155-220 CE) within a year and Zhang Jue died with it. One of the reasons Cao Cao was able to wield the power he did was that a court advisor and general, Liu Yan (d. 194 CE), had persuaded Emperor Lingdi that he should relinquish control of military governors and their provinces and allow each to act according to their own set of circumstances. Since the rebellion was so widespread and seemed to take so many different forms of resistance, the choices of each individual regional commander would be more effective than a blanket imperial dictate. This move would essentially grant regional governors/commanders more or less complete autonomy from the emperor but, even so, Lingdi agreed to the plan.

Rise of the Three Kingdoms

Emperor Lingdi died in 189 CE and his successor was the crown prince Liu Bian who, at around the age of 12, became Emperor Shao of Han. Too young to rule, his uncle He Jin (d. 189 CE) was appointed as his regent. He Jin was the half-brother of the Empress He (d. 189 CE) and was frustrated by the level of control the eunuchs of the palace held over court life and politics. He contacted two of the most powerful warlords, Dong Zhuo (d. 192 CE) and Yuan Shao (d. 202 CE), requesting their full-force presence at the Han capital of Luoyang to support his action in assassinating the Ten Attendants and purging the palace of the eunuchs. The eunuchs learned of his plan, however, and had him killed.

Yuan Shao arrived to find He Jin dead and avenged him by slaughtering the Ten Attendants and then killing the rest of the eunuchs and their support staff. Emperor Shao and his younger brother Liu Xie (d. 234 CE) escaped the carnage at the palace and were on the road to refuge with their attendants and family members at the same time that Dong Zhuo was marching towards Luoyang. Dong found them and brought them back to the city. He was then able to establish himself as the supreme power because he had the emperor and his brother in hand as well as the imperial seal. Shortly afterwards, favoring the younger brother, he had Emperor Shao killed and elevated his younger brother Liu Xie who took the throne name of Emperor Xian (d. 234 CE), the last of the Han emperors.

Dong Zhuo was a self-indulgent and cruel despot according to later Chinese historians but must have had some redeeming features because his army was intensely loyal to him. He remained in power, dictating the policies of the child emperor Xian until he was assassinated by his close confidant, bodyguard, and general Lu Bu (d. 199 CE) in 192 CE.

The agreement Liu Yan had earlier made with emperor Lingdi meant that any regional governor or military commander with enough resources and charisma was essentially his own nation and, after the death of Dong Zhuo, generals such as Liu Bei (d. 223 CE), Sun Quan (d. 252 CE), and Cao Cao (d. 220 CE) fought each other to prove they held the Mandate of Heaven and were the chosen ones to rule all of China. Cao Cao, the most powerful of the three, controlled all of northern China and marched south to take the rest and unify the country under his rule in 208 CE. He was defeated at the Battle of Red Cliffs (208 CE) and driven back north with immense losses.

Afterwards, China was divided into three kingdoms: Cao Wei (led by Cao Cao), Eastern Wu (governed by Sun Quan), and Shu Han (led by Liu Bei). The three kingdoms remained in more or less constant tension until the reunification of China under the Jin Dynasty (266-420 CE) which claimed the Mandate of Heaven by virtue of the act of reunification through military conquest, just as the Qin had done centuries before.

Conclusion

The Jin Dynasty was established by the Sima family when Sima Yan (its first emperor, r. 266-290 CE) forced the abdication of the government of Cao Wei and took control, reuniting the three kingdoms under his rule and thus demonstrating that he held the Mandate of Heaven by restoring order. The Jin Dynasty tried to stabilize the country but was broken by the conflict over succession known as the War of the Eight Princes (291-306 CE) after Sima Yan's death, breaking into Western Jin (266-316 CE) and Eastern Jin (317-420 CE). While the Eastern Jin struggled to maintain control, the country again broke apart during the Period of the Sixteen Kingdoms and was only finally unified by the Liu Song Dynasty (420-479 CE) which also claimed the Mandate of Heaven using the same claim the Jin had earlier.

The Mandate of Heaven, however noble in theory, was consistently invoked by monarchs and would-be monarchs to justify their lust for power, often at the people's expense. The government is a living entity and, as such, self-preservation is its primary goal. Service to the people furthers this goal and so it is in the government's best interests to take care of its people, but “care of the people” can be interpreted in many different ways. Government policies might primarily address land use or health or redistribution of wealth or simply ensuring the majority is employed. There was never a set definition for what it meant to care for the people, and the peasantry who were most affected by this had no voice in trying to form one.

The Yellow Turban Rebellion was the only nationwide political movement instigated by and for the people and that was crushed by the forces which claimed the Mandate of Heaven within a year. The later Jin and Liu Song dynasties who claimed the mandate were little better than the failing Han or any of the three kingdoms – they were simply able to make the best claim for themselves at the time – and, as with earlier ruling houses, their claims were established through military force, not by any policy regarding the greatest good of the people a monarch was supposed to care for.