Rome began as a small city on the banks of the Tiber River in Italy. The Latin tribes (also known as the Latini or Latians) inhabited the region c. 1000 BCE but the founding of the city is dated to 753 BCE. The family was the center and foundation of Roman society with the father as its head.

Rome was a patrilineal society (legitimate descent and inheritance from the father's bloodline) who, among many other deities, worshipped the supreme the sky god Deus Pater (“Father God”) – better known as Jupiter – who was associated with horses, thunder, lightning, storms, and fire. The male deity as head of the pantheon reflected the value of masculinity over femininity in the Latin culture.

The society was clearly patriarchal from an early stage and would continue along those same lines through the history of the Roman Republic (509-27 BCE) and Roman Empire (27 BCE-476 CE in the west, 330-1453 in the east). Although there is a legend that a Trojan woman named Roma, travelling with the hero Aeneas, founded Rome, the far more popular and better-known foundation myth is that the city was founded in 753 BCE by the demi-god Romulus after he killed his brother Remus.

Part of Romulus' story involves the Rape of the Sabine Women which tells of the early Romans abducting women from other tribes, notably the Sabines. These tribes raised an armed force to get their women back but one of the women – Hersilia, who had become Romulus' wife – rallied the other women to stop unnecessary bloodshed and insisted on remaining with the Romans. This story is thought to represent, in mythological form, the vital role of women in Roman society in linking families and maintaining peaceful relations between rival factions through marriage.

Classes & Conflict

The family was the nucleus of Roman society and formed the basis of every community. Stable families made for a stable society and were the most important component of a strict hierarchy based on gender, citizenship, ancestry, and census rank (where one lived and how much land one owned). A citizen was initially defined as any male above the age of fifteen who was a member of one of the original three tribes of the Latins who then dictated the lives of the people politically and socially.

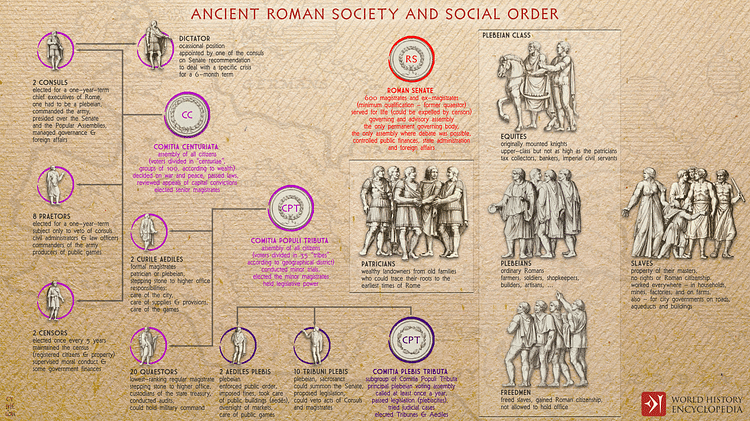

Politically, there was a leader at the top (the consul during the republic, emperor during the empire), the senate, judges, and assemblies while, socially, there was the head of the house (pater familias), his wife, children and, in some cases, his extended family (unmarried sisters, widowed mothers, ageing fathers). The patriarchy, in both spheres (political and social) operated according to the rules of patronage: those in power were obligated to care for those beneath them. The consul, emperor, or head-of-the-house provided their charges with parental care and necessities and, in return, received their loyalty and service.

Society was divided in two classes – the upper-class Patricians and the working-class Plebeians – whose social standing and rights under the law were initially rigidly defined in favor of the upper class until the period characterized by the Conflict of the Orders (c. 500-287 BCE), a power struggle between the Plebeians and the Patricians.

The Conflict of the Orders began when Roman Patricians were campaigning against neighboring tribes for supremacy in the region and needed men for their armies. In 494 BCE, the Plebeians, who made up the bulk of the fighting force, refused to serve in the military until they were given a voice in government. Their grievances were addressed by new laws which allowed them to send their own representative (a tribune) to the senate and, in 449 BCE, by the Twelve Tables, the laws of Rome which were publicly posted for all to see and guaranteed that no one was above the law.

Prior to the conflict, Plebeians were strictly second-class citizens who were forbidden to marry Patricians while, after 445 BCE, this law was changed and Plebeians could marry whomever they chose and had a voice in politics. By the time the Conflict of the Orders ended, Roman society was defined by five social classes:

- Patricians

- Equites

- Plebeians

- Freedmen

- Slaves

Although Patricians have traditionally been presented as landed gentry and the Plebeians as the landless poor, this is a misconception. The Patricians definitely did make up the senate and were the ruling class but there were many powerful Plebeian families and, as Roman history progressed, many Patrician families lost their wealth and standing while Plebeian families' fortunes improved dramatically. Basically, the Patricians were the aristocracy – one had to be born a Patrician – while the Plebeians were everyone else; but plebeian did not necessarily equate to poor. Farmers, plumbers, artisans, teachers, contractors, architects, and many other respectable and lucrative professions were all represented by the Plebeian class.

The Equites (equestrian class, cavalry) were originally the royal mounted knights who were given a certain amount of money to purchase and care for their horse in the period of the early republic and so became associated with commerce and trade. They eventually formed part of the upper-class dealing with business. In 218 BCE, a law was passed prohibiting senators from engaging in commerce because it could compromise their legislative decisions. The equites were patrician-class males, socially inferior to the senatorial class, who ran the banks, collected taxes, operated import-export of goods, and managed trade houses as well as the slave trade.

Freedmen were slaves who had managed to buy their freedom or whose owners had set them free. The freedman (or woman) then became a client of their former owner, relying on his or her patronage. Freed slaves were granted citizenship but could not hold political office. Any children of freed slaves, however, were given full rights as citizens. Freedmen could work any job they were qualified for but often continued in whatever duties they had performed for their former master when a slave.

Slaves were the lowest class in society without any rights and considered property of the master. The quality of life as a Roman slave varied according to one's master and one's job. Life in the mines or in building roads was considerably more difficult than skilled artisan-slaves who worked for craftsmen or served their masters as tutors or musicians. Even so, no matter how easy a slave's responsibilities might seem, they were still subject to the whims of their master who could have them beaten, or even killed, for any reason.

Romans relied heavily on slaves to do whatever jobs they did not want to. Female slaves served their mistresses in every aspect of their lives from helping them bathe, dress, and put on make-up to tending the children, cleaning the home, and assisting in shopping. Male slaves served the master of the house in many capacities, including personal assistants, children's tutor, waiter, butler, bodyguard, overseer on estates, among many others. At one point, the Romans considered instituting a law requiring slaves to wear a certain uniform to identify themselves but decided against this as they feared it would alert the slaves to how numerous they were and possibly encourage a revolt. Slave revolts were a perennial fear of the Romans which was realized in the Spartacus Slave Revolt of 73-71 BCE which terrorized the Romans and haunted them for years after.

Most slaves were foreigners captured in war or taken by slavers but some Romans sold themselves or their children into slavery as a means of paying off a debt. Patrician families sometimes held as many as 1,000 slaves on a small estate and more elsewhere and these slaves served the interests of the state through service to the nucleus of the state: the family.

Family

There is far more documentation on Patrician families than those of the lower class and yet the basic paradigm was the same for both. The father was the head of the family and made all the decisions regarding finance and the raising of children. Fathers had complete control over their children, no matter their age or marital status, from birth until his death (although a son could go to court to demand emancipation from his father if he could prove his father was incompetent or clearly acting against the son's best interests). The father even had the right to decide whether his newborn child would be raised in the house or abandoned.

Childbirth took place in the home, attended by a mid-wife and the slaves of the mother. Men did not participate in childbirth although sometimes, in upper-class homes, a male physician was called to be on-hand in case of a difficult birth. Once the child was born and cleaned, it was placed on the floor in a blanket and the father called into the room. At this point, the father could either pick the child up – signifying it was accepted into the household – or turn away from it.

If the father rejected the child, it was taken from the house and left in the streets to die. A father might reject the child for any reason and, whatever it was, his will could not be challenged. It is likely that more daughters were rejected than sons, since sons were required to carry on the family name and fortune, but newborns could be abandoned simply because another child would place too great a financial burden on the house and, especially if a family already had a healthy son, there was no need for another. These abandoned infants were often rescued by slave-traders who then raised and sold them as slaves.

Women

Women were subject to the will of their fathers throughout their lives, even after they were married, and had no political voice or power. Daughters were taught how to keep and run a household, take care of their husbands, and advance his career. In the late stages of the Roman Republic, women gained more rights but were still under the control of their fathers and husbands.

Even so, women could file for divorce, obtain abortions (with a man's consent), inherit, manage, and sell property, and lower-class women could run businesses, work in stores and restaurants, and operate their own boutiques selling their wares such as jewelry, clothing, and ceramics. Women had no legal right over their children and, in the event of a divorce, the children automatically went to the father. When a woman reached the age of about 15, her father would have already found her a suitable match but some girls were betrothed – often to much older men – at earlier ages.

Marriage

There was no marriage ceremony as recognized in the modern day. Marriage was only legal between two consenting Roman citizens but “consent” was probably not always given freely. If a father had arranged a marriage for his son or daughter, unless he was incredibly lenient, the child was expected to go through with it even if they would prefer not to.

Marriage ceremonies usually took place just after sunrise, symbolizing the new life the couple was embarking on. The ceremony required ten witnesses in order to be legal and, although there was a priest present, he did not officiate. The bride would recite a traditional vow and, afterwards, the wedding party would join in a great feast and then follow the bride and groom to their new home (or the father of the groom's home).

The bride, as she walked, would drop one coin dedicated to the spirits of roads (an offering to bring luck to her future path in marriage) and gave two coins to her new husband, one to honor him personally and the other honoring the spirits of his home. As they walked together, the groom threw nuts and sweets into the crowd and the people who followed them scattered the same in return (a ritual remembered in the present day in throwing rice at weddings) until they reached the groom's house.

Once there, the groom would lift his bride over the threshold to carry her in. Scholar Harold W. Johnston suggests that this may have been “another survival of marriage by capture” referencing the story of the Rape of the Sabine Women (Nardo, 79). While this is possible, it could also have been to prevent the bride tripping and falling (a bad omen) or, more likely, was a symbolic gesture removing her from her old life and carrying her easily into her new one. Close friends and family were then invited into the house where the husband offered his new wife fire and water as essential elements of the home and she kindled the first fire in the hearth. Afterwards, there was more feasting until the new couple retired for the night.

Home & Family

The minimum legal age for a girl to be married was 12 and, for a boy, 15 but most men married later, around the age of 26. This was because males were thought to be mentally unbalanced between the ages of 15-25. They were thought to be ruled entirely by their passions and unable to make sound judgements. Girls were thought to be far more mature at an earlier age (an accepted fact in the modern day) and so were ready for the responsibilities of marriage when they were, often considerably, younger than the groom.

The central purpose of the marriage was to produce and raise children who would become responsible and productive members of society. Since males dominated the social hierarchy, the focus of the home was largely on the first-born son. Nine days after the birth of a male child (eight days for a female), the baby was given a name in the purification ceremony known as the Lustratio and received an amulet to ward off evil spirits. The amulet for boys was called a bulla while a girls' amulet was called a lunula. These objects were made of lead or cloth and, in wealthier homes, gold.

Boys wore the bulla daily until the age of 15 when they were considered a man after a coming-of-age ceremony and became a citizen. Girls wore the lunula until shortly before their marriage when they discarded it along with their childhood toys and clothes and put on women's garments and accessories. The boy would have been raised to learn his father's business and, if a Patrician or Equites, to ride, hunt, and fight. In the time of the Roman Republic, military service was compulsory and so every male was taught martial skills regardless of class while, during the empire, military service was voluntary. Girls, as noted, were raised to become wives and mothers and even though there are notable examples of powerful women in Roman history, these were still married women with children.

The home may have been governed by the father but it was maintained by the mother on every level and this included making it a haven of peace and harmony. Although everyone in the household was responsible for pleasing the gods and spirits, it fell primarily to the woman of the house to ensure that the household spirits were honored daily. These spirits included the panes and penates (spirits of the pantry and kitchen) and the genius (spirit of manhood of the head of the individual home). The lares (spirits of one's ancestors) and parentes (spirits of one's immediate family) were honored through the festival of Parentalia. There were also the manes (collective spirits of the dead) and the lemures (wrathful dead) honored and appeased in the communal festival of Lemuria.

Religion & the State

Religion informed each home, community, and the state. The state sponsored and encouraged homogeneous religious belief and ritual and religion empowered the state. All through the year there were festivals celebrating the gods, great deeds of the past linked with the gods, and the harvest provided by providence. The birthday of the head of the household honored the genius of that household who enabled the father to recognize what needed to be done in any given situation and find the strength and ability to do it. Daily rituals in the home honoring the panes and penates were echoed by the state honoring national gods, exemplified in the role of the Vestal Virgins and the sacred fire of the goddess of hearth, home, and family, Vesta.

The greatest festival of the Roman calendar was Saturnalia, honoring the agricultural god of seed, sowing, and the harvest, Saturn. Saturnalia was celebrated, in some periods, from the 17th-23rd of December and during the festival all work stopped, businesses closed, and traditions were suspended. This was the only time of the year when the head of the household relinquished responsibility and a junior member of the house took control. All laws and rituals were relaxed, slaves were allowed to join the festivities as equals, and parties replaced council meetings, assemblies, and building-project planning boards.

People dressed in colorful clothes, decorated their homes with flowers, wreaths, and ceramic figurines, and invited friends and family in for feasts and drink while communal celebrations welcomed everyone in the neighborhood. Gifts were exchanged, usually including small figurines of Saturn as the giver of all good gifts and, the next day, everyone recovered from the festivities and went back to their normal lives.

Saturnalia, obviously, was the ancient precursor to the modern-day Christmas celebration. Scholars generally agree that Jesus Christ was probably born in the spring but the Church, in keeping with its policy of Christianizing popular pagan holidays, chose the 25th of December to celebrate Christ's birth in order to replace Saturnalia with their own holiday. Saturnalia was only the most popular and welcome of many religious festivals throughout the year, however, and these all served to bind Roman society together as a single unit with the head-of-state as the head-of-the-household of the cohesive family of the Roman people.