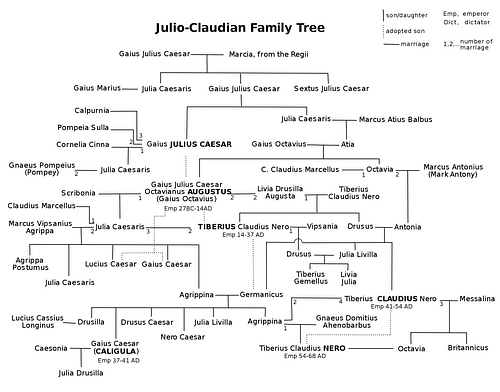

The Julio-Claudians were the first dynasty to rule the Roman Empire. After the death of the dictator-for-life Julius Caesar in 44 BCE, his adopted son Octavian - later to become known as Augustus (r. 27 BCE - 14 CE) - fought a civil war against his father's enemies to eventually prevail and become the first Roman emperor. He would be succeeded by his adopted son Tiberius (14-37 CE), his great-grandson Caligula (37-41 CE), his great-nephew Claudius (41-54 CE) and lastly his great-great-grandson Nero (54-68 CE).

In her biography of Agrippina the Younger, historian Emma Southon wrote how Romans obsessed on the concept of family lineage: the family was the most important thing in one's life. This could especially be seen in the Julio-Claudians. While the Claudians were considered one of the oldest Roman families, the Julians could trace their family from Augustus to Julius Caesar and finally to the mythical Aeneas, the ancestor of Romulus and Remus, and his mother, the goddess of love Venus. The two families came together initially when Augustus married his third wife Livia Drusilla, but more significantly when Germanicus (a Claudian) married Agrippina the Elder (a Julian).

Augustus

Upon becoming the first citizen of Rome, Augustus initiated laws and reforms for a city in turmoil. The Roman Senate granted him almost unlimited power. Among these were tribunician powers: the ability to convene the Senate, propose legislation in the assemblies, and veto any legislation enacted by those same assemblies. Augustus became the law. Often seen as a micro-manager, many of his reforms brought about a more efficient bureaucracy. He saw a city consumed by moral decay and believed that restoration of the old Roman religion and renewed trust in the traditional gods would help restore the confidence of the people. Augustus realized that to rebuild the city of Rome he had to restore both the faith and values of the Roman Republic.

He brought about a return of many of the old, popular festivals and increased the number of public games, even reinstituting the Secular Games. He built theaters, aqueducts, and 82 temples, including the Temple of Mars Ultor and the Temple of Apollo. He also fostered a love of the written word and Roman literature flourished; it was a time of Livy, Horace, Ovid, and Virgil. Most of all, he established the Pax Romana or Roman Peace, a period of relative stability across the empire.

Tiberius

His heir was the reluctant Tiberius, the son of his third wife Livia. Most historians agree that Tiberius never wanted to be emperor. He was forced to divorce his beloved, pregnant wife Vipsania and marry Augustus' daughter Julia. It was a move that ensured his place as heir. He had been an excellent general but shied away from much of the ceremony that followed an emperor, giving respect to the authority of the Senate. He began but did not finish many public works projects; they would be completed by Caligula. In the last years of his reign, Tiberius became more paranoid and inflicted an ever-increasing number of treason trials. The rigors of running an empire and the constant nagging of an ever-controlling mother were too much for him, so he moved to the isle of Capri in 26 CE, leaving the daily routine of ruling the empire to his advisor and prefect of the Praetorian Guard Sejanus. Sejanus would eventually cross the line (believing himself to be the true emperor) Tiberius had him executed. Over time Tiberius became more reclusive, remaining on Capri where he died in 37 CE. Upon his death the throne fell to his nephew Caligula. Many in Rome were happy to see the young Caligula ascend to the throne, replacing the highly unpopular Tiberius.

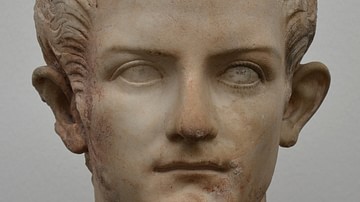

Caligula

Caligula “Little Boots” or Gaius is an enigma. While there are many modern historians who see some of the good he did, most ancient historians are critical of his time in power. While the first year of his reign was promising, completing many building projects begun under his uncle and increasing the number of games and festivals, he became as paranoid as Tiberius and instigated a number of purges and treason trials of his own. This fear extended to his own family when he exiled his own sister Agrippina the Younger. Those who are critical of Caligula cite his debased lifestyle, an attempt to name his favorite horse Incitatus a consul, and his failed effort to invade Britain. However, to his credit, he gave long overdue bonuses to the Praetorian Guard, built a lighthouse at Boulogne, began work on new aqueducts and even built a new amphitheater in Pompeii. Finally, after only four years as emperor, in January 41 CE, Caligula was murdered by members of the Praetorian Guard. His wife, Caesonia, and daughter were murdered as well, and, in a final insult, the man he had ridiculed for years was named his successor, Claudius.

Claudius

Claudius, considered dim-witted by many (including his own family) was actually the best of Augustus' successors. First of all, he took vengeance against Caligula's assassins. And with little or no political or military experience, he successfully invaded Britain and annexed Thrace, Lycia, Mauretania, and Noricum. In doing so, he brought a return to relative peace to Rome with the re-establishment of the rule of law. He built a new harbor at Ostia, established an imperial civil service, and brought about agrarian reform.

However, he could be as merciless as those who ruled before him. Like his predecessors, he was paranoid, quick to anger, and did not hesitate to put suspected enemies to death. Claudius had at least 35 senators and over 400 others executed or forced to commit suicide. He even had all the Jews expelled from the city. Likewise, he was also unlucky in marriage. While his marriage to the unfaithful Messalina bore him a son, Britannicus, his marriage to Caligula's sister Agrippina - a possible suspect in his death - brought him an heir, Nero.

Nero

While remembered by many as having fiddled while Rome burned, he was, in his defense, out of the city at the time. Upon his return, he helped many escape the fire, providing housing and food. Although he rebuilt a safer city, he also took the opportunity to build himself a Golden Palace. The early part of Nero's reign was considered by many to be good – many Romans believed him to be generous and kind. To provide himself with time to pursue other interests, he restored much of the Senate's power. There were extravagant games, plays, concerts, chariot races, gladiatorial tournaments, and taxes were reduced.

Like his predecessors, however, he became paranoid and untrusting. Unfortunately, he also suffered, like Tiberius, under years of an overly protective mother who believed herself to be the true force behind the throne. Unfortunately, Agrippina was bold enough to boast of her influence, which eventually brought her death. Finally, opposition to his cruel reign grew, and in 68 CE a commander from the west was successful in a coup. Nero committed suicide (with a little help) and Galba sat on the throne.

Government

The Roman government lay completely in the hands of the emperor. Under the authority of the emperor, the Senate became more and more ceremonial. They would only really endorse the wishes of the emperor. The emperor's demands became law. However, throughout its existence even under the emperor and despite its loss of power, the Senate remained the domain of the wealthy. Prior to the rise of the emperor, much of the power lay in the hands of the assemblies: the Comitia Centuriata, the Concilium Plebis, and many smaller tribal assemblies. These assemblies, together with the consuls and tribunes, would almost fade into non-existence under Augustus and his successors.

With the consent of the Senate, Augustus took the title of princeps or “first citizen.” He assumed the title of consul and provincial governor, which gave him complete control of the Roman army. He controlled the imperial patronage, and no one could hold any office without his consent. To maintain authority and to protect himself, he created the Praetorian Guard, a personal army. In time, as many of the emperors in the west became weak, the Guard's authority grew and grew, even hand-picking the emperor.

However, while many of the Senate's duties were diminished, there were always the lesser officials, those who helped run the day to day activities of the empire. In the days of the Republic, these positions were used as a pathway to becoming consul. The first such office was that of the praetor who had judicial duties, holding both civic and provincial jurisdiction. Next one could become quaestor, a financial officer, who controlled the treasury and collected taxes and tributes. Another important position was that of an aedile, whose responsibilities included supervising public records and managing public works, but this office disappeared during the imperial period.

Family

From the time of the Republic through the Empire, family was a crucial part of a person's life. And, in Rome, the family was based on the concept of paterfamilias, the male head of the house (the father or eldest male) who had the power of life and death over all members of the family. At birth a child would be presented to the father; he could accept or reject the child, especially if he had more than one daughter as more than one daughter would mean more than one dowry. An unwanted child would be left by the roadside to die from exposure. A father could even sell his children into slavery. As women's rights increased, the concept of paterfamilias began to fade. While he may have been the one making the economic decisions, it was the women who ran the household. One of a woman's primary duties was the preparation of the family meals. And, like everything else, Roman diet depended on a person's economic status.

While the wealthy lounged on pillows and were served by slaves, many of the poor depended on the government's monthly allotment of grain, the annona. Along with the grain, most subsisted on lentils, some vegetables, porridge, olive oil, but rarely any wine. There was little meat, few spices, and very few fruits. There were no potatoes, tomatoes, corn, rice, or sugar; these foods would only be introduced to Europe later in time. Education for many Romans was also an important duty of the mother. The male children of the wealthy enjoyed tutors in math, reading and writing, and later they might travel to Athens to study philosophy. Boys of the poorer families might remain illiterate but could enter into apprentice programs while girls learned domestic skills.

Society

From the time of the Republic, Rome was a class society. At the very top were the plebians and patricians. Initially, the patrician class ran the government, they were members of the Senate and named the consuls until reforms and the Twelve Tables allowed the plebeians to partake and the Concilium Plebis was created. Patricians were often descended from the first families of Rome and lived a life of leisure. Plebeians, although having achieved some political rights, worked as laborers, craftsmen or tradesmen: cobblers, butchers, and leather workers. Eventually, patricians and plebeians would be allowed to marry. However, work for more affluent Romans ended around noon. The rest of the day was spent in leisure in Roman baths, pubs, or games.

At the bottom of the pyramid, of course, were the slaves who remained the property of their owner, at least until they could buy their freedom becoming freedmen. There were many slaves who were literate, often from Athens, serving as accountants or even as tutors for the children of the wealthy. Those who were illiterate did manual work. Freedmen could marry and even become a citizen but were barred from holding public office. By the time of Augustus one-half of Rome was either slave or freedmen.

One step above the slaves were women. They were expected to marry young (an arranged marriage) and have children. Agrippina the Younger married her first husband Domitius at the age of 13. Although initially restricted from appearing in public, women would eventually be able to attend the theater, games, and even go to the baths, of course, separately from the men. In time laws were passed to allow women to initiate divorce proceedings and even own property. Under Augustus, adultery was made a crime. Occasionally, poor women would serve as hairdressers, midwives, or dressmakers for the wealthy. Although unable to vote or participate in the government, many women proved to be highly influential such as Livia, Agrippina the Younger, and her mother Agrippina the Elder.

City Life

With the responsibility of ruling in the hands of the emperor, the average Roman did not care about the day-to-day running of the government. He or she was mostly concerned with daily existence. A Roman would wake up each and every morning, eat a small breakfast, work, and then relax. Of course, many of the city's poor prayed that there would be food on the table and they would not be evicted. Most of the citizens, not all of them poor, lived in apartment buildings called insulae. The floor on which one resided reflected their income; lower apartments were far more comfortable than those above it, being more spacious with separate rooms for dining and sleeping. The higher floors were cramped, often one room, with little access to natural light, running water, or even a toilet; most had to use the public toilets.

Refuse - even human waste - provided its residents with a terrible stench and a breeding ground for disease. The Roman author Juvenal said walking through the streets of Rome was walking through filth. Most of the upper floors of the insulae were overcrowded and extremely dangerous. People lived in constant fear of fire, collapse, or even possible flooding. Although laws were passed under Augustus from keeping them from becoming too tall (some were nine stories), the laws were often ignored. With no street lights and a prevalence of crime, there was little to no street traffic at night. The wealthy, those who did not live in villas, lived in a domus with multiple rooms, glazed windows, gardens, and even a bathing pool. The front of a domus served as a shop or tabernae where the owner would oversee his business. Behind the shop was an atrium or reception area where guests were welcomed or business conducted.The city streets were very narrow, sometimes only six feet wide, so if a fire did occur, there was little chance of help. After the great fire under Nero, the streets would be widened and balconies built to provide some safety in case of an emergency.

Leisure

Regardless of one's economic status, Romans could enjoy leisure time spent at the gladiatorial games or in the public baths. The baths or thermae were a part of everyday life. Most Romans - especially the patricians and equestrians - bathed at least once or twice a week. To the wealthy, the baths were a place to socialize or conduct business. Many baths had a gymnasium for exercise, a library for reading, and even food stalls. Fed by an aqueduct, there were three separate rooms - a frigidarium (cold), tepidarium (warm), and lastly the caldarium (hot). Slaves were used to maintain the various room temperatures and assist the wealthy, even giving massages.

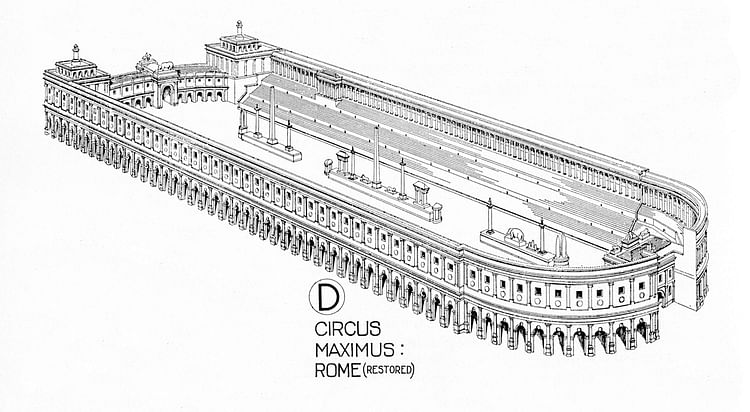

If one were not at the baths, the festivals and games kept the population of Rome happy and content. It was always good publicity for the emperor to be seen at the games. There were over 100 days a year (159 by the time of Claudius) set aside for public holidays, religious festivals and games. One of the most famous places to see the games was the Circus Maximus which seated 300,000 spectators. Built in the 6th century BCE and lying between the Palatine and Aventine hills, it hosted gladiatorial fights, wild animal hunts, religious ceremonies, chariot races, and even plays. Nero built the Circus of Nero, but it, unfortunately, was used mostly for executions.

Conclusion

The Julio-Claudians ruled Rome for almost a century. Augustus inherited a republic that was in desperate need of repair. Assuming almost absolute power, he instituted reforms that stabilized the economic and social condition of Rome. Unfortunately, his successors did not follow his example. Under Nero, the city burned. Society, however, has a way of enduring, and so did Rome. The city was rebuilt and stayed the imperial city (at least in the west) for three more centuries.

The average Roman citizen was happy when they were fed and entertained, and it was the role of the emperor to see that every Roman was kept happy. There were plenty of games to attend and festivals to celebrate. The city was kept safe from invasion until 410 CE and trade kept the grain bins full. The Class division had been there since before the Republic. However, the average Roman, poor or rich, appeared content. Nero died, with assistance, in 68 CE, and was succeeded by a military commander, Galba. He would prove ineffective; the year that followed became known as the Year of the Four Emperors. The last of these four, Vespasian, would bring some stability to the empire again.