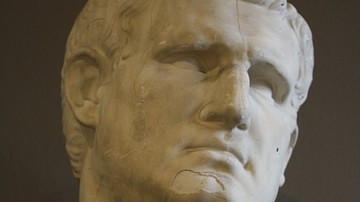

Propaganda played an important role in Octavian (l. 63 BCE - 14 CE) and Mark Antony's (l. 83 – 30 BCE) civil war, and once victorious at the Battle of Actium (31 BCE), Octavian returned home to become the first Roman emperor. The decade preceding their civil war was a decisive one. In 43 BCE, Octavian, Antony, and Lepidus (l. 89/88 – 13/12 BCE) formed the Second Triumvirate to "restore order to the state" and declare war on Julius Caesar's assassins. During these pivotal years, Antony was away in the East, preparing for his invasion of Parthia. Octavian mostly stayed in and near Italy, strengthening his image and solidifying his authority among the Roman Senate and people.

In Sicily, Sextus Pompey (l. 67-35 BCE) was cutting off Italy's grain supply, causing widespread famine. Something had to be done, so Octavian seized the opportunity to win acclaim. Octavian and his top general, Marcus Agrippa (l. 63-12 BCE), went on to defeat Sextus Pompey at the Battle of Naulochus in 36 BCE and when he returned home, the "Senate and the people of Rome welcomed Octavian as a hero, ready to shower him with honors" (Southern, Augustus, 85). The following year, Octavian embarked on the Illyrian campaigns where he would once again prove immensely successful. By contrast, Antony's campaign in Parthia ended disastrously, putting him and Octavian in very different positions of power and how they were perceived.

From the Second Triumvirate, Lepidus was exiled by Octavian in 36 BCE and was no longer involved in political life. That left Octavian and Antony as the two remaining triumvirs. Their shaky alliance would steadily deteriorate, each of them waging a war of pernicious propaganda, paving the way for the final civil war of the Roman Republic, culminating in the Battle of Actium. Later, Octavian also propagandized his victory at Actium as the battle which legitimized his role as bringer of peace, freedom, and stability to Rome.

Pre-Actium Propaganda

Both the pre-war escalation between Octavian and Antony and Octavian's justification for the civil war itself were heavily founded on propaganda. The first major turning point occurred in 35 BCE when Octavia (l. 69 - 11 BCE), Octavian's sister and Antony's wife, took a trip to Athens to visit Antony. At this point, Antony and Cleopatra, the Queen of Egypt, have been already lovers since 40-41 BCE and were seldom apart from each other for long. Octavia brought him vital supplies, travel animals, clothing, money, armor, and elite soldiers of the Praetorian Guard. Antony accepted and received her gifts, but did not see her and had a messenger send her back to Rome.

Octavian seized the opportunity to depict Antony in a bad light. After all, Octavia was a noble Roman woman going above and beyond her duties as a wife, and Antony shamefully rejected her. Although it was not common for the wife of a provincial governor to accompany her husband to his province, it was also not common for a husband to “keep a royal mistress so publicly” (Goldsworthy, 182). According to Plutarch, Octavian permitted Octavia to visit Antony in Athens. This lends credibility to the idea that Octavian orchestrated the whole scene to make Antony look bad. Because Octavian was in and close to Italy in these years and Antony was away in the east, Octavian was in a much better position to gain favor with the citizens and the Roman army. Octavian, in addition to his successful campaign in Illyria, had also recently defeated Sextus Pompey's grain supply blockade and Italy was “moving to something close to a normal, stable existence” (Goldsworthy, 182).

The following year, in 34 BCE, Antony and Cleopatra held an extravagant triumphal ceremony in Alexandria to celebrate Antony's annexation of Armenia, which was perceived as “theatrical, arrogant, and to reveal a hatred of Rome” (Plutarch, Life of Antony, 54.3). The ceremony was reminiscent of a Roman triumph but took place in a foreign land. There were two thrones of gold, one for Antony and one for Cleopatra, with lower seated thrones for their sons. The purpose of this lavish ceremony was to confirm the Queen's power and to distribute territories and kingdoms to Antony and Cleopatra's children. Antony declared Cleopatra the Queen of Egypt, Cyprus, Libya, and Syria. To their children went Armenia, Media, Parthia, Phoenicia, Syria, and Cilicia. This was distasteful and an affront to Roman sensibilities. To make matters worse, Cleopatra wore “a robe sacred to Isis, and was addressed as the New Isis” (Plutarch, Life of Antony, 54.6).

Octavian, like most of the “people of Italy, found Egyptian beliefs alien” and worthy of mistrust (Bleicken, 257). He took advantage of the disgraceful Alexandrian ceremony and the propaganda assault towards Antony continued. Octavian brought the matter of Antony's ceremony to the Roman Senate and denounced it to the Roman people in an attempt to garner public disapproval of Antony's behavior. Antony was depicted as un-Roman and enslaved “to the passion and the witchery of Cleopatra” (Dio, Roman History, 49.34). By contrast, Octavian modeled himself as the quintessential Roman who was declared imperator (victorious commander), brought peace to Rome, did not have an Egyptian mistress, and was working for the betterment of Rome.

The propaganda was not one-sided. Antony claimed that Octavian “first betrothed his daughter to his son, Antonius and then to Cotiso, king of the Getae, at the same time asking for the hand of the king's daughter for himself.” (Suetonius, Life of Augustus, 63.2). These were inflammatory claims from Antony, according to which, Octavian promised to wed his infant daughter, Julia, to some Illyrian tribe, as well as Octavian himself marrying the king's daughter. Antony also revived stories of Octavian's embarrassing conduct at the Battle of Philippi as well as salacious rumors concerning a sexual relationship between Octavian and his adoptive father, Julius Caesar (l. 100 - 44 BCE).

The final straw was the matter of Antony's will. Octavian jumped at the opportunity to expose the incriminating clauses of its content, which was described as “fatal to Antony's reputation in Rome” (Zanker, 72). The will was deposited in the Temple of Vesta, and when Octavian went and illegally requested the will, the Vestal Virgins refused to give it to him. However, they told him that if he wanted the will, he could enter the temple and just take it and they would not stop him. So, he went and took it. Octavian read it aloud to the entire Senate, even if most of them thought it highly inappropriate to call Antony to account “while alive for what he wished to have done after his death” (Plutarch, Life of Antony, 58.3).

In the will, Antony listed the children he fathered with Cleopatra as his heirs. However, Octavian placed the most importance on the fact that Antony, even if he were to die in Rome, wished to be sent to Cleopatra to be buried in Alexandria. This revived rumors that Antony wanted to move the capital from Rome to Alexandria. Octavian magnified and distorted the embarrassing content of Antony's will which was put in stark contrast with Octavian's proper Roman behavior. After all, Octavian had no plans to be buried in a foreign land. Instead, he would have a massive tomb for him and his family in the heart of Rome, known as the Mausoleum. It is possible Octavian began planning this monstrously large tomb once he discovered Antony's burial arrangements, to place even more distance between the two.

The tension between the two triumvirs had come to a boiling point and another civil war was imminent, but because Antony had been successfully depicted as not Roman, this would not be a civil war. Octavian's propaganda was loud and clear: Antony did not belong to Rome, but to Egypt and Cleopatra. Octavian attacked Antony's romanitas (Roman-ness); he was now hopelessly enraptured by Cleopatra, to Egypt, and their 'strange' deities.

when he sees that this man [Antony] has now abandoned all his ancestors' habits of life, has emulated all alien and barbaric customs, that he pays no honor to us or to the laws or to his fathers' gods, but pays homage to that wench [Cleopatra] as if she were some Isis or Selene... but being a slave to that woman, he undertakes the war and its self-chosen dangers on her behalf against us and against his country... Therefore let no one count him a Roman, but rather an Egyptian (Part of Octavian's speech against Antony in Cassius Dio's Roman History. 50. 25-26)

Octavian justified the need for war not as Roman against Roman, but Rome against Cleopatra and the East. To the war-weary Romans, this was much easier to accept than another civil war. Octavian rallied Rome and Italy to defend herself against a foreign enemy. In 32 BCE, he officially declared war on Cleopatra in the Temple of Bellona where ancient rites preliminary to war were performed. Plutarch called these proceedings as directed towards Cleopatra but was really against Antony. Some senators defected to Antony, but the majority stayed and pledged loyalty to Octavian. Augustus later wrote, “The whole of Italy voluntarily took oath of allegiance to me and demanded me as its leader in the war in which I was victorious at Actium.” (Augustus, Res Gestae Divi Augusti, 25).

Post-Actium Propaganda

As soon as word came of his victory. The people of the capital unanimously bestowed upon him votes of praise, statues, the right to the front seat, an arch surmounted by trophies, and the privilege of riding into the city on horseback, of wearing the laurel crown on all occasions, and of holding a banquet with his wife and children in the temple of Capitoline Jupiter on the anniversary of the day on which he had won his victory, which was to be a perpetual day of thanksgiving. (Cassius Dio on the news of Octavian's victory at Actium in his Roman History, 49.15.1)

This post-Actium propaganda was different than the political invective between Octavian and Antony leading up to the battle. Actium was used as a symbol for peace, stability, and a return of the Republic to the people of Rome. The victory at Actium “came to be regarded as some kind of secular miracle, out of which the new rule of Augustus was born” (Zanker, 84).

Divine Intervention & the New Foundation Myth of Rome

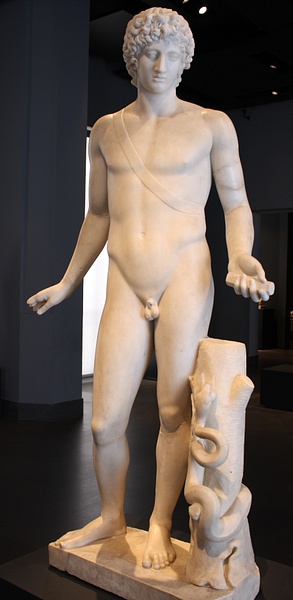

The story of Rome's foundation in 753 BCE by Romulus and Remus, descendants of the demigod, Aeneas, is part historical and part mythical. In Octavian's victory at Actium, myth was also inseparably mingled with history. After his victory, Octavian did not want to accept sole responsibility for success. Rather, it had been the god Apollo who helped deliver victory to the Romans and freed them from Egypt's 'barbaric' customs and the Egyptian religion.

Apollo was incredibly significant during and in Actium's aftermath. There happened to be a temple of Apollo close to Augustus' home, and Apollo also 'surveyed' the Battle of Actium from his temple on the Actian hills. The gods were intervening in human affairs to determine the outcome, and divine intervention was commonly depicted in Actium propaganda. Agrippa, Octavian's right-hand man and general, is depicted towering over his fleet of ships as “backed by winds and gods” (Virgil, Aeneid, 8. 780). In one section, Virgil (l. 70 - 19 BCE) even describes the battle as a fight between the Roman gods and the 'monstrous' Egyptian gods:

Among them the Queen, rattling Egyptian timbrels, called up her warships, still unaware of the twin snakes at her back. Barking Anubis and monstrous gods of every description fought against Neptune, Minerva, and Venus. (Virgil, Aeneid, 8.797-801)

Apollo, arched in his temple overseeing the battle had intervened and saved Rome from “shame and humiliation, and Octavian had been their instrument. Thanks were therefore due to the god Apollo.” (Bleicken, Augustus, 261). After Actium, Octavian built a new temple for Apollo on Palatine Hill which was “visible over a wide area, including from the Forum” (Goldsworthy, Augustus, 225). This victory was not just like any other; it closely connected the divine to Octavian himself.

It is important to remember that in antiquity, there was no distinction between myth and history. The two were inseparably interconnected. Reading about the history of ancient Rome, and you will read about Antony and Hercules, Caesar and Venus, Augustus and Aeneas. The fabric of divinity and gods was woven into Rome's very foundation. Today, we can separate what was historical and what was mythical. However, there was no such concern in antiquity. For example, Jupiter, Aeneas the demigod, and Venus all appear in the opening books of Livy's History of Rome.

Octavian already had a strong ancestral relation to the gods. His adoptive father was the deified Julius Caesar who claimed that the Julius name came from Iulus, who was the son of Aeneas whose mother was the goddess, Venus. Later, part of Octavian's name was Divi Filius which means “son of the god”. In connecting the Battle of Actium to the divine, Octavian strengthened his already strong divine aura and lent credibility to his rule. This created a kind of mythical foundation story of the new Rome, in which Octavian and Apollo were the main protagonists. Actium marked the beginning of a new era of peace and stability.

Images, Symbolism, Triumphs, & Literature after the Battle of Actium

Upon entering Rome, he was awarded three consecutive days of 'triumphs' - a massive celebratory procession for a successful commander - for his military victories in Illyria, Egypt, and Actium. Monuments and coins depicted Octavian's virtus (military excellence) at Actium. For instance, on one decorative monument, Octavian is shown holding Neptune's trident and riding a sea chariot pulled by hippocamps (a mythological creature with a horse's body and a fish's tail) above the crashing foamy waves. Some coins commemorating the Battle of Actium show Octavian with a laurel wreath and inscriptions that read Libertatis Populi Romani Vindex (savior of the freedom of the Roman people). Of course, this meant freedom from being enslaved by the 'enchantress' Cleopatra and the East. Other coins show the goddess Victory perched over the prow of a ship, once again connecting divinity and Octavian.

Household items such as lamps and vases adorned with Actium images reached the furthest parts of the Empire and “attest to the fact that Augustus' rule found broad and ready acceptance” (Hölscher, Monuments of the Battle of Actium). Cementing the idea that the victory at Actium brought peace was the closing of the Arch of Janus in 29 BCE, the city gates, which allowed people in and out of Rome. This was an incredible honor, as the gates were closed only in times of peace and had only been closed three times in the history of Rome. According to Augustus, in his part-biography, part-resume Res Gestae Divi Augusti (Deeds of the Divine Augustus). He does not mention Antony or Cleopatra. Instead, he claims to have “extinguished the flames of civil war” (34).

The Roman literature of the time also praised Octavian and the defeat of Cleopatra. Virgil dedicated a section of the Aeneid to the naval battle, Propertius wrote elegies praising Octavian and ridiculing Cleopatra, Horace wrote an epode, “A Toast to Actium”, in which he celebrated the victorious Octavian, inviting us to drink and celebrate over Cleopatra's defeat. While the various monuments, arches, and coins were overtly propagandistic in their attempt to create a very particular image of a new era of peace and freedom, it is much more difficult to write off the poetry of the time as mere propaganda. These were celebrated works of art that endured millennia. Virgil's Aeneid, for example, stands alongside Homer's epic poems as the most important and celebrated works of antiquity. Their poems continue to be studied up to the present day. Historian Adrian Goldsworthy claims that there is no evidence of Augustus' “direct intervention in the words they wrote” and that “there is no good reason to doubt that Virgil and the others were sincere in the views they expressed” (310-11). That said, while these works of art cannot be labeled as mere propaganda, their praising nature and demonization of Cleopatra certainly went hand in hand with the actual propaganda of the time.

Conclusion

Propaganda was a vital element in the escalation between Octavian and Antony before the civil war erupted. While they were both fighting for dominance, the propaganda came from both sides: there was the Octavian faction and the Antony faction. After Octavian defeated Antony and Cleopatra, there was only one faction - Octavian's. Antony, or any of Octavian's enemies for that matter, is nowhere to be found on the monuments celebrating Actium. After 31 BCE, Antony's supporters went over to Octavian's side, pledging their loyalty to the new ruler and some were even tasked with building monuments and temples celebrating Actium.

Once Octavian proved victorious, the Battle of Actium became emblematic of Rome's new beginning. Imagery of the naval battle flooded the empire, from the biggest monuments to the smallest household items. This was in contrast to before Augustus, where “memorials of Roman statesmen were rare outside Rome” (Hölscher, 311). Actium was the departure point from a century of civil war into a new era of peace, freedom, and stability. It laid the foundation for Augustus' Principate. Octavian descended from Aeneas and Romulus, the original founders of Rome, and now he was the founder of a new Rome.