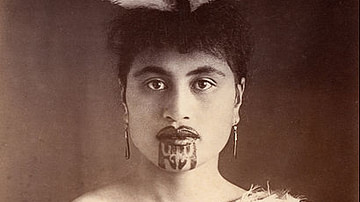

The Bay of Islands is a subtropical region in New Zealand's far north and is a popular destination for big-game fishing, sailing, and dolphin watching. It is an area rich in the history of Maori (Māori in their own language) and European (Pākehā) relations and conflict.

The American author of adventure novels, Zane Grey (1872-1939 CE), catapulted the region to international fame when he visited the Bay of Islands in the 1920s CE. A renowned angler, Grey brought along an entourage that included cooks and cameramen. He managed to upset New Zealanders with his criticism of local fishing practices and his lavish lifestyle at a time when economic depression was looming.

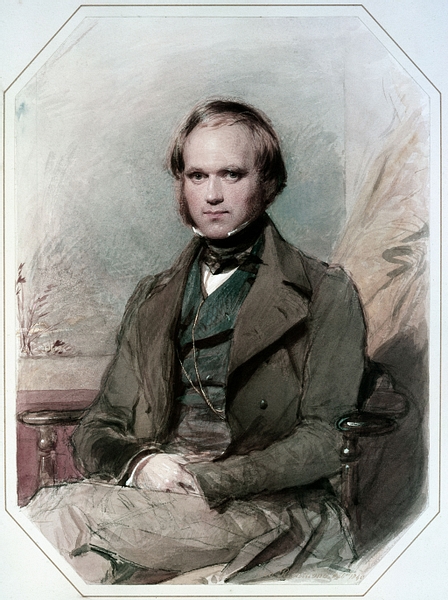

But before Zane Grey's notorious visit, the Bay of Islands was known for its role in establishing a model farm that was visited and admired by the English naturalist Charles Darwin (1809-1882 CE). The farm was part of a once-extensive mission station that hosted the second signing of the Treaty of Waitangi, New Zealand's founding document (1840 CE).

The Waimate Mission station and farm sits atop a small rise surrounded by the sloping pastoral landscape of Waimate, Bay of Islands and preserves New Zealand's early colonial architecture and missionary history. The British missionaries who set up the mission can be given credit for introducing European farming practices to New Zealand, and their story is one of courage and resilience.

The Founding of Te Waimate Mission

The Waimate Mission station is now called Te Waimate Mission (te being “the” in Maori), and it was established by the Church Missionary Society of London when the site was chosen in 1830 CE by the Reverend Samuel Marsden (1765 – 1838 CE). The Society was founded in 1796 CE with the objective of carrying the Christian message to distant lands, particularly Africa, India, and New Zealand.

Marsden had already set up Anglican missions in the Bay of Islands at Rangihoua (1814 CE), Kerikeri (1820 CE), and Paihia (1823 CE), and he strongly believed that an inland mission station was needed to bring missionaries in closer contact with Maori tribes (iwi). But a strong reason for locating the mission in Waimate was the distraction to missionaries and Maori of the lawless outpost of Kororareka.

Kororareka means 'The Place of the Sweet Penguins' in Maori language (Te Reo). It was anything but in the early 1800s CE. Kororareka (now called Russell) was the biggest whaling station in the southern hemisphere and ships, sealers, sailors, and merchants would visit to "refit and refresh". Drunkenness and prostitution were the town's main attractions. Observers referred to Kororareka as the “hell hole of the Pacific” or “Gomorrah, the scourge of the Pacific”.

Marsden was troubled by what he saw and decided that twelve miles inland from Kororareka was a safe enough distance away from the mischievous ways of sailors and the temptation of alcohol. Missionaries had visited the Waimate area for many years prior to 1830 CE. Marsden had also held talks with the Maori chief (rangatira), Hongi Hika (1772-1828 CE), in 1823 CE about the possibility of establishing a farm in the area.

What the missionaries found were abundant fields of maize, sweet potatoes (kumara) brought to New Zealand from the Pacific Islands by early Maori settlers, and native tree ferns the height of which prevented Marsden and his missionaries from getting a clear view to survey potential land sites. Marsden most likely selected the area because of the volcanic clay loam soil, and he felt it would be fertile land for agriculture because he was also a farmer of some note.

The Church Missionary Society selected the Reverend William Yate (1802-1877 CE) to be the resident clergyman of the mission, along with lay missionaries George Clarke (1823-1913 CE), Richard Davis (1790-1863 CE), and James Hamlin (1803-1865 CE). Men who took up missionary work often came from interesting and varied backgrounds; Yate was a scholar, Clarke was a gunsmith, while Davis had been a successful tenant farmer in Dorsetshire, England, and Hamlin a weaver by trade.

Yate signed the deed of purchase for 735 acres (297 hectares) in September 1830 CE following negotiations with the Ngapuhi tribe (Ngāpuhi iwi) and walking over the region for many months to find the right parcel of land. The missionaries also needed to respect the land where Maori laid their dead before permanent burial (wahi tapu).

By 1840 CE, not one of these men remained at the mission. Years of backbreaking work clearing the land of tangled scrub and tall bracken ferns along with building the mission houses had taken their toll. Clarke was offered a position in the new colonial government when New Zealand became a British possession in 1840 CE.

Yate left in disgrace having been accused of improper relations with an officer on board the Prince Regent, which brought him from England. On hearing the news, Marsden sent Yate back to England, where the Church Missionary Society promptly dismissed him. His colleagues in New Zealand burnt his belongings and shot his horse.

Despite this fall from grace, work started on the permanent homes for the missionaries and the model farm, with George Clarke taking a leading role.

The Mission Houses

Three houses of similar design were originally constructed but the only one remaining on the site is Clarke's house, which was built in 1832 CE. The house is the second oldest building in New Zealand and displays remarkable craftsmanship. The visitor can wander through the 187-year-old house and stroll around the lush subtropical gardens filled with monkey puzzle trees and Norfolk Island pines.

The two-storeyed Georgian style (1714-1830 CE) architectural design was adapted to suit the climate of the Bay of Islands, which can be humid with heavy rainfall. Wide verandahs, low-pitched hipped roofs, and three small dormer windows give the house its graceful appearance.

Clarke was most likely the designer of the homes, having seen similar styles in Sydney, Australia, and he also supervised the construction and trained Maori in carpentry work. The interior was simple but practical. On the ground floor, there are main rooms either side of a central entrance hall. There are smaller rooms at the back including a skillion – a lean-to or shed attached to the house and sometimes used for cooking or additional accommodation. Upstairs, the visitor will find a small corridor from which three bedrooms branch off. Clarke's home also had a cellar. There was no internal bathroom or plumbing, and missionary wives fetched water from wells and washed clothes outside. The kitchen was a large open fireplace that can still be seen today.

The missionaries, assisted by Maori labour, moulded and baked 50,000 clay bricks and felled 700,000 ft (213 m) of timber from local forests for planks, boards, and furniture.

The houses took 14 months to build and one of the missionaries described a typical day beyond the construction:

Mixing medicine, visiting the sick, scolding the idle, rousing the hippish, and remonstrating with the obstinate, have taken up the whole of my day; indeed, it is no small portion of my time which is thus employed. Examined a few candidates for Baptism in the evening. (Standish, 18)

The Model Farm

Because the Waimate district was densely populated by Maori, the missionaries considered it an ideal opportunity to set up a model farm and teach English agricultural methods. Marsden was convinced that if modern farming practice and English crops were introduced, war between tribes (iwi) would cease and Christianity and useful training in the skills of weaving, smithing (metalwork), and carpentry would follow.

Maori practised shifting cultivation, which meant that land was cleared by burning, crops were then planted and the site was abandoned a few years later as Maori moved on. The missionaries chose not to follow the Maori practice of using ash from the burning of trees and scrub as fertiliser. Instead, the missionaries cleared the tangled bush by hand with bean or weed hooks, hoes, ploughshares, and harrows. By 1835 CE, 35 acres (14 hectares) had been prepared and planted with wheat.

Wheat was an essential crop because flour had to be imported from New South Wales, Australia at considerable cost to the mission. Sickles were used to harvest the wheat, and threshing was done by the flail (an ancient manual tool with a long wooden handle and a shorter free-swinging stick that separates the grains from the husk).

Caterpillars, rats, and mice caused the loss of stored grain and the climate often proved too wet for the successful growth of wheat. But by December 1834 CE, the mission had constructed the first water-powered mill to be built in New Zealand. By 1837 CE, 30,520 pounds (approximately 14,000 kg) of flour had been produced for both the mission and Maori.

Vegetable gardens were laid out and schools were built. In the orchard, pears, rhubarb, figs, peaches, plums, quinces, gooseberries, apricots, and apples were planted. Most seeds were imported from England, and it is probably in these seeds that the troublesome Scottish Thistle was introduced into New Zealand. Sheep were run and dairy cattle grazed. The cattle caused some tension with Maori as they disturbed sacred (tapu) land.

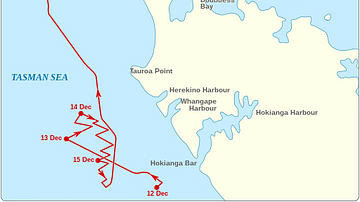

In 1835 CE, 26-year-old Charles Darwin (1809-1882 CE) spent nine days in the Bay of Islands after arriving on the HMS Beagle, which had been circumnavigating the globe since December 1831 CE. Darwin had collected fossils and scientific specimens on his trips ashore and kept a diary full of observations and drawings that ultimately led to his theory of natural selection. The Beagle anchored off Kororareka flanked by its many liquor shops and brothels. Darwin wrote in his diary: “This little village is the stronghold of vice."

Thankfully, he was invited to spend Christmas at the mission, and he made the journey by foot and boat, guided by a Maori chief (rangatira). Darwin went by canoe (waka) as far as Haruru Falls before he had to follow tracks through dense bush.

He admired the mission where he enjoyed cups of tea and cricket on the lawn, recording his thoughts in his diary on December 23, 1835 CE:

At length we reached Waimate; after having passed over so many miles of an uninhabited useless country, the sudden appearance of an English farm house & its well dressed fields, placed there as if by an enchanter's wand, was exceedingly pleasing.

In the same diary entry, Darwin referred to seeing an English oak tree, which was near the mission station. It had started its life as an acorn brought by ship from England in 1824 CE by Richard Davis and was planted at Waimate around 1830 CE. Sadly, this majestic oak was knocked down by a strong wind in 2018 CE.

Te Waimate Mission seemed to be the one bright spot in Darwin's short visit to New Zealand for on December 27, 1835 CE Darwin wrote: "I am disappointed in New Zealand, both in the country & in its inhabitants. After the Tahitians, the natives appear savages."

Darwin's diaries, manuscripts, and private papers are available online and make for fascinating reading. Should you visit Te Waimate mission, you will walk in the footsteps of Darwin.

St. John's Church is also a part of the mission and is a stunning example of Gothic Revival (c. 1740s - early 1900s CE) architecture. Charles Darwin would not have seen or visited this church as it was built in 1871 CE as a replacement for the 1839 CE chapel. But the original stone font still stands.

The Decline of Te Waimate Mission

By the end of the 1830s CE, the mission had run into considerable trouble. The soil in the Waimate region was found to be unsuitable for growing the crops English missionaries were used to back home. Maori were also farming their own land and selling their produce for a good return. An increasing number of English settlers preferred to raise stock rather than crops. And it was costing too much effort and money to keep the mission going, especially since wheat and flour could now be bought more cheaply elsewhere in New Zealand.

George Clarke joined the new colonial government as Chief Protector of Aborigines, and his house was left empty until 1842 CE when Bishop Selwyn (1809-1878 CE) arrived and rented the mission to train Maori candidates for ordination.

The mission suffered a blow in 1840 CE with the death of a little Maori girl who attended the infants' school. She had been living at Clarke's house and Hōne Heke (c. 1807/1808 – 1850 CE), an influential Maori chief (rangatira) and war leader, arrived with a party of Maori to confront Clarke who was away from the mission at that time. Hōne Heke left, taking mission Maori with him, and persuaded them to have nothing further to do with Clarke and the missionaries.

The story of the mission then becomes one of deteriorating Maori-European relations. The Bay of Islands lost its trading predominance to Auckland and this affected Maori economically. Many Maori also could not understand what was meant by New Zealand's cession to Great Britain.

Hōne Heke led aggrieved Maori down the path of escalating clashes that culminated in the Northern Wars of 1844-1846 CE. The neutrality of the mission was compromised when large reinforcements of troops arrived and used the mission as British headquarters for several months. Casualties from the fierce Battle of Ohaeawai (1845 CE) were buried in the graveyard of St. John's church. Hōne Heke was defeated in 1846 CE.

Te Waimate mission never really recovered. The Maori population declined in the Bay of Islands from an estimated 8,000 in 1843 CE to around 2,500 in 1878 CE. Gum-digging and land selling were more profitable exploits. Although the mission school managed to attract 60 pupils in 1846 CE, a bout of whooping cough and dysentery caused the death of six children.

The Church Missionary Society leased or sold land surrounding the mission until only a few acres around Clarke's house were left. Over the years, shingles and weatherboards have been replaced but the Te Waimate Mission house is largely as George Clarke and Maori builders constructed it, complete with period furniture.

How to Get There

The Bay of Islands is a three-hour drive north of Auckland (North Island) and the nearest large town is Kerikeri. If you drive from Auckland, it is a further 20 minutes from Kerikeri to Te Waimate Mission.

You can also fly into Kerikeri airport and hire a car or take a private tour around the Bay of Islands that will include the mission. The entry fee to the house and gardens is NZD 10.00 (approximately USD 6.50), and summer and winter opening hours are available on the mission's website.

If you visit the sun-soaked Bay of Islands, make sure to stop off at the Makana Chocolate Boutique in Kerikeri and then pop into their chocolate factory next door. This will be sure to give you enough energy to spend hours at the mission exploring the house and gardens - treading the path that Charles Darwin once walked.