A vision of the afterlife is articulated by every culture, ancient or modern, in an effort to answer the question of what happens after death. Ancient Persia had the same interest in this as any culture of the past or in the present day and provided one of the most interesting, and compassionate, answers.

The human concern with mortality informs not only the scriptures of world religions but the greatest literary works. The Mesopotamian Epic of Gilgamesh – considered the oldest epic tale in the world – is centered on finding meaning in life in the face of inevitable death and innumerable works since have explored the same problem.

Shakespeare's Hamlet sums up this concern in his line, “The undiscovered country, from whose bourn/ No traveler returns, puzzles the will” (Act III.i.79-80) but Hamlet is simply among the most articulate speakers to make the observation which could arguably be defined as the central, underlying preoccupation of the human race. The inevitability of death defines human life and what happens afterwards has inspired many striking visions of the afterlife, from the ancient Egyptian Field of Reeds to the Greek Hades and the many other conceptions of the life after death, including the well-known destinations of heaven and hell.

Although this last concept of two possible final destinations is most closely associated with Christianity and Islam in the modern day, it is actually an ancient Persian creation which, along with influences from other cultures, contributed to the visions of both faiths. The Catholic concept of Purgatory was also earlier imagined by the Persians in their Hamistakan, a place for the souls of those whose good and bad deeds were equal; these would remain in equilibrium until the end of time when they would be reunited with Ahura Mazda.

The early Persian concept of an afterlife was similar to that of Mesopotamia – a dark, dreary land of shadows – but this would be revised and ornamented, elevating one's death to a moment of ultimate triumph and joy or dramatic despair and failure and, ultimately, give meaning to one's life in what waited beyond death.

Gods, Spirits & Death

The religion of the ancient Persians arrived in the region of Iran with their migration from the area of Greater Iran (the Caucasus, Central Asia, South Asia, and West Asia) sometime around the 3rd millennium BCE. What the original faith consisted of is unknown, but it is thought to have then been influenced by the Elamites and the people of Susiana who were already settled in the area.

This was an oral belief system, and remained so as it developed, and all that is known of it comes from much later works written after the prophet Zoroaster (c. 1500-1000 BCE) had dramatically reformed it. It is therefore difficult to know which aspects were pre-Zoroastrian but, generally, a good idea is given by Zoroastrian works such as the Avesta, Vendidad, and Bundahisn which reference earlier beliefs. Even so, some post-Zoroastrian concepts seem to have been applied to the earlier model and there is no way of knowing what these might have replaced.

The Persian religion was initially polytheistic with a pantheon of deities led by a single powerful god, Ahura Mazda. The pantheon addressed the same kinds of concerns as any other polytheistic faith with different deities presiding over their own area of specialization. Mithra was the god of the rising sun, covenants, and contracts; Anahita was the goddess of fertility, water, health and healing, and wisdom and, sometimes, war. The world was full of spirits, good and bad, and there were supernatural beings like the peri (faeries) or jinn (genies) who could influence human thought and behavior.

The gods of the Persian pantheon existed to care for and protect humans from the threats of the evil forces – later known as daevas – who were led by the malevolent spirit Angra Mainyu. Angra Mainyu was the enemy of Ahura Mazda and the other gods who, unable to finally overturn the gods' great design, could only do what he could to disrupt it at every turn and, in response, Ahura Mazda turned his best efforts at destruction to positive ends.

When Ahura Mazda created the beautiful Primordial Bull, Gavaevodata, Angra Mainyu killed it. Ahura Mazda then lifted the bull's corpse to the moon where it was purified and, from its purified seed, came all the animals in the world. When Ahura Mazda created the first human, Gayomartan, Angra Mainyu killed him as well. From his purified seed, however, the first mortal couple were born – Mashya and Mashyanag – who lived in paradise with their god and all of nature.

Angra Mainyu disrupted this as well, whispering to the couple that he was their actual creator and Ahura Mazda an evil deceiver. Mashya and Mashyanag listened to his lies and were cast out of paradise. Death now entered the world and, with their children, a limited time for every human life. Ahura Mazda managed to even turn this to good, however, in allowing each human being to decide for themselves whether to follow him or Angra Mainyu and, in doing so, granted humanity an ultimate meaning in life: one could live well fighting for Good or meanly struggling for Evil.

Early Persian Afterlife

When a person died, their soul lingered near the body for three days before departing for the subterranean land of the dead. This was a dark kingdom, similar to the Mesopotamian vision of the Realm of Ereshkigal, Queen of the Dead, where the souls roamed in an eternal shadowy twilight. In the Persian vision, this land was governed by King Yima (also given as Yama), the first great mortal king who, though initially favored by the gods, sinned through the wiles of Angra Mainyu and fell from grace. Like Ereshkigal, Yima's central purpose seems to have been to keep the dead in his realm and the living out.

As in other belief systems, the continued existence of these dead depended entirely on the prayers and remembrance of the living. Survivors spent the first three days after a person's death in prayer and fasting because this was considered the most dangerous time for the soul. The soul would be disoriented and susceptible to demonic attack. A ritual developed known as the sagdid (“glance of the dog”), in which a dog was brought into the presence of the corpse to drive away evil spirits. Dogs were considered the best defense against evil entities because they could see what humans could not and their bark was thought to make such spirits flee. The dog was brought in three times and, if at any time it hesitated or seemed unwilling, this was taken to mean it had not driven off the entity. It would then be led in up to nine times until the spirit was thought to be gone and the body could be prepared for interment.

The dead person was either buried or, more commonly, placed on an outdoor scaffolding now referred to as a Tower of Silence where the body was picked clean by scavengers; once that was done, the bones were interred. While the living were taking care of the body, the soul of the deceased was wandering in the Realm of Yima. There is some lack of clarity on when this next phase took place but, at some point, the soul would have to cross a dark river by boat – an event known as the Crossing of the Separator – where good souls were separated from bad and assigned their places. It is possible that this event took place when the dead first arrived from the world and the crossing separated them from the land of the living and brought them to Yima's Realm.

The Crossing of the Separator may have involved Mithra in his role as god of covenants since it would have been understood that the soul had a contract with its creator, Ahura Mazda, and if it had honored that contract with a good life, it would be rewarded; if not, it would be punished for following the lies of Angra Mainyu. There is reference to Mithra holding the scales which balanced a person's good deeds against the bad and a person was then rewarded or punished accordingly. The angels Rashnu (the later judge of the dead) and Suroosh (a guardian angel) may have also taken part in this but might be later additions. Some form of judgment took place after death, however, and the soul was sent to a new home in the afterlife.

Once they were there, it was up to the living to keep their memory alive. The first year was especially important because the soul was adapting to its new home and would feel lost and lonely; it therefore needed extra attention from the living. The next of kin was primarily responsible for this and rites of remembrance would last up to 30 years or the next of kin's death. Food was regularly prepared for the deceased in the afterlife, prayers and sacrifices made for their well-being, and they were remembered especially every New Year's Eve, when they were thought to return to visit.

Zoroaster

At some point between c.1500-1000 BCE, a priest named Zoroaster received a vision which would dramatically change Persian religious understanding. By the bank of a river, a being of light appeared to him, identifying itself as Vohu Manah (“good purpose”) and informing Zoroaster that the Persians' religious beliefs were mistaken. There was only one god, he was told, and this was Ahura Mazda; all other so-called “gods” were simply emanations from the Supreme Being.

Zoroaster became the prophet of this new vision, preaching it to everyone he could, but was rejected, threatened, and had to leave his home. His first convert is traditionally said to be his cousin but this made no significant difference in the acceptance of his vision. It was only after he had converted the king Vishtaspa, who then converted his entire realm, that Zoroastrianism became an influential belief system.

Ahura Mazda now became the Supreme God and Angra Mainyu his eternal enemy. It was understood earlier that human beings needed to choose which of these deities to devote their time on earth to but now this became the meaning of life. Humans were created with free will and, whichever path one chose, defined one's values and the course of one's existence. Life was, then, a battle between the forces of Good and those of Evil and everyone, at birth, was required to choose a side. In accepting Zoroaster's vision, one dedicated one's self to the principles of Good Thoughts, Good Words, Good Deeds, making friends from enemies, and practicing charity toward all, among other virtues.

Later Persian Afterlife

As noted, aspects of Zoroastrianism existed prior to Zoroaster's vision and no doubt played a part in the original faith but, as they are clearly delineated post-Zoroaster, they are usually considered to have been introduced – or at least revised – by him.

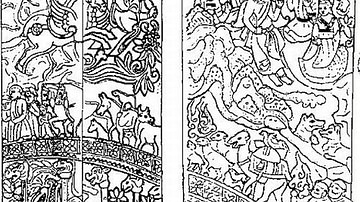

At birth, one's soul (urvan) was sent into the body by one's higher self (the fravashi) in order to experience the material world and fight on the side of Good. The fravrashi would do its best to assist the soul in its struggles through life and waited for it after death. When a person died, the urvan lingered for three days by the corpse while the gods weighed their good and bad deeds. On the fourth day, the urvan traveled to the Chinvat Bridge – the span between the living and the dead – where it was reunited with its fravashi. Two dogs guarded the bridge who would welcome good souls and snarl at the bad. The urvan and fravashi would join and be met by Daena, the Holy Maiden, who mirrored the urvan's conscience; to the justified, she was a beautiful young woman while, to the condemned, she was a withered hag.

The angel Suroosh would appear, to guard the soul against demonic attacks from the abyss and guide the soul across the bridge. For the justified soul, the bridge would widen and be easy; for the condemned, it would narrow and be difficult. At the far end stood the angel Rashnu who would have received the tally of one's good and bad deeds and render judgment. Scholar A. T. Olmstead comments:

One's own conscience, whether of Righteous or Liar, will determine his future award. With Zoroaster as associate judge, Ahura Mazda himself will, through his counselor Righteousness, separate the wise from the unwise. Afterward, Zoroaster will guide those he has taught to invoke Mazda across Chinvato Peretav the Bridge of the Separator. Those who wisely choose will proceed to the House of Song, the Abode of Good Thought, the Kingdom of Good Thought, the Glorious Heritage of Good Thought, to which one travels by the sciences of the Saviors to pass to their reward. There shall they behold the throne of the mightiest Ahura and the Obedience of Mazda, the felicity that is with the heavenly lights. But the foolish shall go to the House of the Lie, the House of Worst Thought, the home of the daevas, the Worst Existence. Their evil conscience shall bring them torment at the Judgment of the Bridge and lead them to long future ages of misery, darkness, foul food, and cries of woe. (101)

There were four levels of paradise ascending upwards from the bridge and four dark hells descending downwards. Rashnu would decide where the soul deserved to go and it is understood that the soul itself would recognize the justice of this decision. The highest level of paradise was the Heaven of Eternal Light where the soul would live in the radiant company of Ahura Mazda himself. In between the lowest heaven and the highest hell was the purgatory of Hamistakan from which the other levels of hell descended to the lowest pit in the House of Lies, the Hell of Eternal Darkness, where the soul was tormented and experienced complete loneliness; no matter how many other souls were present, it would always feel alone.

Even so, there was hope for salvation for every soul – even the worst – because Ahura Mazda was completely loving and could not bear the thought of any soul eternally lost. In time, a messiah would come – the Saoshyant (“One Who Brings Benefit”) – and would bring about the Frashokereti (End of Time). The world as human beings knew it would end and all would be gathered to Ahura Mazda. The souls in the House of Lies would be liberated and Angra Mainyu would be destroyed. Afterwards, everyone would be reunited with their loved ones and would live in peace and harmony with Ahura Mazda eternally.

Conclusion

This vision was suppressed in Persia following the Muslim Arab invasion and fall of the Sassanian Empire in 651 CE. Zoroastrians were persecuted, their altars destroyed, libraries burned, and mosques erected in the sacred places. Even so, Zoroastrian and earlier Persian beliefs regarding death and the afterlife would influence the developing Muslim vision just as it had the earlier Christian religion and the even earlier Judaism. The Persian concepts of a single god, a good life defined by moral conduct, personal responsibility for one's soul and salvation, an afterlife of paradise or hell, judgment after death, and a messiah – to name only a few concepts – predate the development of all three of these religions.

One of the most interesting Persian contributions to Islam is the reimagining of the Chinvat Bridge in the Hadiths. In Islam, a Hadith is an extra-Quranic account of the life of the Prophet Muhammad as well as beliefs, customs, and actions Muhammad would approve of.

The Hadith Bukhari, among others, describes the As-Sirat – the Bridge to Paradise – which is the final obstacle believers must face before they are welcomed into heaven. The bridge will only be crossed by believers (Muslims) since all other souls are bound for hell by rejecting the faith. The bridge is described as slippery and “thin as a hair and sharp as a sword” with thorns, clamps, hooks, barbs to impede one's crossing. Further, the bridge is wide when the soul steps onto it and then narrows dramatically; beneath it are the fires of hell which lap at the souls as they make their way along it (Bukhari, Book 97:65). The souls of the most devout will fly across the bridge but most will struggle.

Every religious response to Hamlet's observation regarding the undiscovered country which waits after death reflects the culture that creates it and can never, objectively, be more than that. No one knows what comes after death except the dead and they have never been known to be very vocal in describing their realm. The Persian vision, however, with its emphasis on living the best life one can in accordance with the highest principles, as well as its all-inclusive concept of ultimate salvation, is among the most admirable ever conceived. Even though there is no way of knowing whether it could be true, the beauty of the vision inspires hope that it could, or should, be; and hope for an afterlife of reunion with all one has lost is finally the only positive response to death.